Other Conditions that May be a Focus of Clinical Attention

In the fifth edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), in a section called Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention, there is a list of conditions that are not mental disorders but that have led to contact with the mental health care system. In some instances, one of these conditions will be noted during the course of a psychiatric evaluation (e.g., divorce), although no mental disorder has been found. In other instances, the diagnostic evaluation reveals no mental disorder, but a need is seen to note the primary reason for contact with the mental health care system (e.g., homelessness).

In some cases, a mental disorder may eventually be found, but the focus of attention or treatment is on a condition that is not caused by a mental disorder. For example, a patient with an anxiety disorder may receive treatment for a marital problem that is unrelated to the anxiety disorder itself.

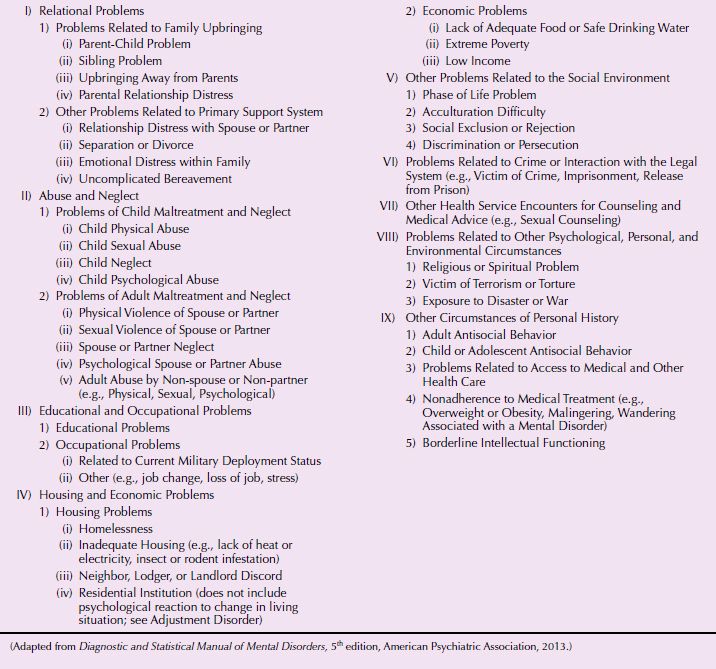

Table 25-1 lists the many conditions that may be a focus of clinical attention or that may influence the diagnosis, treatment, or course of a mental disorder that is contained in DSM-5. The list of conditions that make up this category cover the entire life cycle from infancy through childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and old age. The list of conditions covers almost every conceivable life circumstance from divorce to problems related to being in military service. In one sense, they represent the vicissitudes of life or, as Shakespeare has Hamlet state, “the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune.” Each of these conditions or circumstances is capable of having a profound input on a particular mental illness or on the human experience in general.

Table 25-1

Table 25-1

Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention

The conditions discussed in this chapter include the following: (1) malingering, (2) bereavement, (3) occupational problems, (4) adult antisocial behavior, (5) religious or spiritual problem, (6) acculturation problem, (7) phase of life problem, (8) noncompliance with treatment for a mental disorder, and (9) relational problems. Problems related to the maltreatment and abuse of children is covered in Section 31.19c, and problems related to the physical and sexual abuse of adults is covered in Chapter 26.

MALINGERING

Malingering is the deliberate falsification of physical or psychological symptoms in an attempt to achieve a secondary gain such as avoiding military duty, avoiding work, obtaining financial compensation, evading criminal prosecution, or obtaining drugs. Under some circumstances, malingering may represent adaptive behavior—for example, as mentioned below, feigning illness while a captive of the enemy during wartime.

Malingering should be strongly suspected if any combination of the following is noted: (1) medicolegal context of presentation (e.g., the person is referred by an attorney to the clinician for examination or is incarcerated), (2) evident discrepancy between the individual’s claimed stress or disability and the objective findings, (3) lack of cooperation during the diagnostic evaluation and in complying with the prescribed treatment regimen, and (4) the presence of antisocial personality disorder.

Epidemiology

A 1 percent prevalence of malingering has been estimated among mental health patients in civilian clinical practice, with the estimate rising to 5 percent in the military. In a litigious context, during interviews of criminal defendants, the estimated prevalence of malingering is much higher—between 10 and 20 percent. Approximately 50 percent of children presenting with conduct disorders are described as having serious lying-related issues.

Although no familial or genetic patterns have been reported and no clear sex bias or age at onset has been delineated, malingering does appear to be highly prevalent in certain military, prison, and litigious populations and, in Western society, in men from youth through middle age. Associated disorders include conduct disorder and anxiety disorders in children and antisocial, borderline, and narcissistic personality disorders in adults.

Etiology

Although no biological factors have been found to be causally related to malingering, its frequent association with antisocial personality disorder raises the possibility that hypoarousability may be an underlying metabolic factor. Still, no predisposing genetic, neurophysiological, neurochemical, or neuroendocrinological forces are presently known.

Diagnosis and Clinical Features

Avoidance of Criminal Responsibility, Trial, and Punishment. Criminals may pretend to be incompetent to avoid standing trial; they may feign insanity at the time of perpetration of the crime, malinger symptoms to receive a less harsh penalty, or attempt to act too incapacitated (incompetent) to be executed.

Avoidance of Military Service or of Particularly Hazardous Duties. Persons may malinger to avoid conscription into the armed forces and, after being conscripted, they may feign illness to escape from particularly onerous or hazardous duties.

Financial Gain. Modern malingerers may seek financial gain in the form of undeserved disability insurance, veterans’ benefits, workers’ compensation, or tort damages for purported psychological injury.

Avoidance of Work, Social Responsibility, and Social Consequences. Individuals may malinger to escape from unpleasant vocational or social circumstances or to avoid the social and litigation-related consequences of vocational or social improprieties.

An owner of a previously successful photographic equipment supplier declared bankruptcy in a way that the government maintained was illegal. Subsequently, the government indicted the defendant on various counts of fraud. The defendant’s counsel maintained that the defendant was too depressed to cooperate with him and that, because of that depression, he experienced memory loss that made it impossible to understand what had occurred and therefore impossible to provide a meaningful defense. The government’s forensic psychiatrist evaluated the defendant to ascertain the nature of his depression and to determine whether it was causing cognitive problems.

When asked early in his evaluation when his birthday was, he responded, “Oh, what does it matter? It was in the 40s or 50s.” Similarly, when queried about where he was born, he said, “Some place in Hungary.” Even when pressed for more specifics, he refused to elaborate. Yet, at many points later in his evaluation, he responded with complete, often detailed, information about transactions not related to those for which he had been indicted. It was the impression of the evaluator that the defendant was malingering in a gross and inconsistent fashion, incompatible with the kinds of decreases in cognitive skills that occasionally attend major depression. (Adapted from case of Mark J. Mills, J.D., M.D., and Mark S. Lipian, M.D., Ph.D.)

Facilitation of Transfer from Prison to Hospital. Prisoners may malinger (fake bad) with the goal of obtaining a transfer to a psychiatric hospital from which they may hope to escape or in which they expect to do “easier time.” The prison context may also give rise to dissimulation (faking good), however; the prospect of an indeterminate number of days on a mental health ward may prompt an inmate with true psychiatric symptoms to make every effort to conceal them.

Admission to a Hospital. In this era of deinstitutionalization and homelessness, individuals may malinger in an effort to gain admission to a psychiatric hospital. Such institutions may be seen as providing free room and board, a safe haven from the police, or refuge from rival gang members or disgruntled drug cronies who have made street life even more unbearable and hazardous than it usually is.

A robust, neatly attired man presented to the psychiatric emergency department in the early-morning hours. He stated that “the voices” were worse and that he wished to be readmitted to the hospital. When the psychiatrist challenged him, observing that he had just been discharged that afternoon, that he routinely left the hospital in the morning and demanded rehospitalization at night, and that, despite multiple hospitalizations, his reported history of hallucinations had been increasingly doubted, the man became belligerent. When the psychiatrist still refused to admit him, the patient grabbed the psychiatrist’s clothes, threatening him but inflicting no harm. The psychiatrist asked the hospital police to escort him off the grounds. The patient was told he could seek readmission to his regular ward during the day. Subsequent contact with the patient’s ward revealed that their diagnoses were substance abuse and homelessness; his apparent schizophrenia appeared never to have been an actual issue in his treatment. (Courtesy of Mark J. Mills, J.D., M.D., and Mark S. Lipian, M.D., Ph.D.)

Drug Seeking. Malingerers may feign illness in an effort to obtain favored medications, either for personal use or, in a prison setting, as currency to barter for cigarettes, protection, or other inmate-provided favors.

The plaintiff, a woman in her late 20s, was injured while dancing at a club. Although her claim initially appeared bona fide, subsequent investigation cast doubt on the mechanism of injury that she claimed—namely, that a misplaced electrical cord under a carpet caused her to slip. This was true, she claimed, even though she had to been dancing in a particularly jerky manner that could have easily caused problems without tripping.

Subsequently, she sought medical and surgical treatment for torn cartilage in her injured knee. Even though the initial surgery went well, she kept reinjuring the knee with various “slips.” As a result, she requested narcotic analgesics. A careful medical record review revealed that she was obtaining such medications from multiple practitioners and that she had apparently forged at least one prescription.

In reviewing the case before binding arbitration, it was the opinion of the orthopedic and psychiatric consultants that, although the initial injury and reported pain were real, the plaintiff consciously elaborated her injuries to obtain the desired narcotic analgesics. (Courtesy of Mark J. Mills, J.D., M.D., and Mark S. Lipian, M.D., Ph.D.)

Child Custody. Minimizing difficulties or faking good for the sake of obtaining child custody can occur when one party accurately accuses the other of being an unfit parent because of psychological conditions. The accused party may feel compelled to minimize symptoms or to portray him- or herself in a positive light to reduce chances of being deemed unfit and losing custody.

Differential Diagnosis

Malingering must be differentiated from the actual physical or psychiatric illness suspected of being feigned. Furthermore, the possibility of partial malingering, which is an exaggeration of existing symptoms, must be entertained. Also, the possibility exists of unintentional, dynamically driven misattribution of genuine symptoms (e.g., of depression) to an incorrect environmental cause (e.g., to sexual harassment rather than to narcissistic injury).

It should also be remembered that a real psychiatric disorder and malingering are not mutually exclusive.

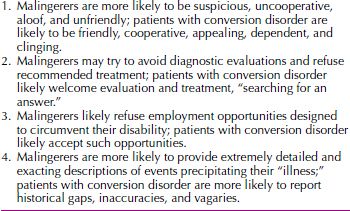

Factitious disorder is distinguished from malingering by motivation (sick role vs. tangible pain), whereas the somatoform disorders involve no conscious volition. In conversion disorder, as in malingering, objective signs cannot account for subjective experience, and differentiation between the two disorders can be difficult. Table 25-2 lists some variables that may aid in distinguishing between these two conditions.

Table 25-2

Table 25-2

Factors Aiding in the Differentiation between Malingering and Conversion Disorder

Course and Prognosis

Malingering persists as long as the malingerer believes it will likely produce the desired rewards. In the absence of concurrent diagnoses, after the rewards have been attained, the feigned symptoms disappear. In some structured settings, such as the military or prison units, ignoring the malingered behavior may result in its disappearance, particularly if an expectation of continued productive performance, despite complaints, is made clear. In children, malingering is most likely associated with a predisposing anxiety or conduct disorder; proper attention to this developing problem may alleviate the child’s propensity to malinger.

Treatment

The appropriate stance for the psychiatrist is clinical neutrality. If malingering is suspected, a careful differential investigation should ensue. If, at the conclusion of the diagnostic evaluation, malingering seems most likely, the patient should be tactfully but firmly confronted with the apparent outcome. The reasons underlying the ruse need to be elicited, however, and alternative pathways to the desired outcome explored. Coexisting psychiatric disorders should be thoroughly assessed. Only if the patient is utterly unwilling to interact with the physician under any terms other than manipulation should the therapeutic (or evaluative) interaction be abandoned.

BEREAVEMENT

Normal bereavement begins immediately after or within a few months of the loss of a loved one. Typical signs and symptoms include feelings of sadness, preoccupation with thoughts about the deceased, tearfulness, irritability, insomnia, and difficulties concentrating and carrying out daily activities. On the basis of the cultural group, bereavement is limited to a varying time, usually 6 months, but it can be longer. Normal bereavement, however, can lead to a full depressive disorder that requires treatment. Some grieving individuals present with symptoms characteristic of a major depressive episode such as depressed mood, insomnia, anorexia, and weight loss. The duration of grief and bereavement vary considerably among different cultural groups and with the same cultural group. The diagnosis of depressive disorder is generally not given unless the symptoms are still present 2 months after the loss. However, the presence of certain symptoms that are not characteristic of a “normal” grief reaction may be helpful in differentiating bereavement from depression. These include (1) guilt about things other than actions taken or not taken by the survivor at the time of the death, (2) thoughts of death other than the survivor feeling that he or she would be better off dead or should have died with the deceased person, (3) morbid preoccupation with worthlessness, (4) marked psychomotor retardation, (5) prolonged and marked functional impairment, and (6) hallucinatory experiences other than thinking that he or she hears the voice of or transiently sees the image of the deceased person.

OCCUPATIONAL PROBLEMS

Occupational problems often arise during stressful changes in work, namely, at initial entry into the workforce or when making job changes within the same organization to a higher position because of good performance or to a parallel position because of corporate need. Distress occurs particularly if these changes are not sought and no preparatory training has taken place, as well as during layoffs and at retirement, especially if retirement is mandatory and the person is unprepared for this event. Work distress can result if initially agreed-to conditions change to work overload or lack of challenge and opportunity to experience work satisfaction, if an individual feels unable to fulfill conflicting expectations or feels that work conditions prevent accomplishing assignments because of lack of legitimate power, or if an individual believes he or she works in a hierarchy with harsh and unreasonable superiors.

Work Choices and Changes

Young adults without role models or guidance from families, mentors, or others in their communities too often underestimate their lifetime potential abilities to learn a trade or earn a college or postgraduate degree. In addition, women and members of minority groups often feel less prepared to accept work challenges, fear rejection, and do not apply for jobs for which they are qualified. On the other hand, men, in fields in which they are underrepresented, often and confidently move up the career ladder faster (glass elevator). As part of initial interviews for evaluation of occupational problems, patients should be encouraged to consider their heretofore unrecognized, unadmitted talents; long-held, yet unexpressed, dreams and goals regarding work; actual successes in work and school; and motivation to risk learning what they would find satisfying.

Minorities and those in low-paying and low-skilled jobs too often have less job security. Business and institutional reorganization and consequent downsizing, factory closings, and moves affect many, often leaving these workers feeling hopeless and helpless about future employment, on welfare, angry, and depressed.

With ongoing and often sudden downsizing of corporations and businesses, men and women continue to struggle with unexpected job loss and premature retirement even when finances are not an issue. In addition, men, in particular, define themselves by their work roles, and thus experience more occupational distress from these changes. Women may adjust faster to retirement, but they often have less financial security than men do (white women earn approximately 80 cents on the dollar, and African American and Hispanic women earn even less for comparable work); women have generally been in lower status work positions, find themselves widowed more often than men, and are more likely to be caring for children, grandchildren, and elderly relatives. Women represent more of the single working parent group and the working poor.

Stress and the Workplace

More than 30 percent of workers report that they are under stress at work. Workplace distress is implicated in at least 15 percent of occupational disability claims. Expected distress follows recognized and uncontrollable work changes—downsizing; mergers and acquisitions; work overload; and chronic physical strains, including work noise, temperature, bodily injuries, and strain from performing computer work. According to one study, the top ten most stressful jobs in 1998 were (1) president of the United States, (2) firefighter, (3) senior corporate executive, (4) race car driver, (5) taxi driver, (6) surgeon, (7) astronaut, (8) police officer, (9) football player, and (10) air traffic controller. People who work under deadlines, such as bus drivers, are subject to hypertension.

Work frustration can also arise from an individual worker’s unrecognized (and therefore unresolved) psychodynamic issues, such as working appropriately with superiors and not relating to one’s supervisor as a parent figure. Other developmental issues include unresolved problems with competition, assertiveness, envy, fear of success, and inability to communicate verbally in a constructive manner.

After the September 11, 2001, World Trade Center tragedy, a 32-year-old, married male firefighter, who had been away on vacation that day with his wife and children, began to exhibit changed behaviors at home and at work. At home, he appeared not to listen to his two children and, instead, focused his attention on television sporting events. At work, he also appeared to be more focused on cooking the same dinners for his peers and watching television than on interacting verbally with his remaining peers and the new chief. In the course of several months, a chaplain visited the station several times and talked to the firefighters about survivor guilt and the 9/11 tragedy, and the firefighter began to return somewhat to his former healthier behaviors. (Courtesy of Leah J. Dickstein, M.D.)

Often, work conflicts reflect similar conflicts in the worker’s personal life, and referral for treatment, unless there is insight, is in order. Some studies have found that massage therapy, meditation, and yoga at intervals during the work day relieve stress when used on a regular basis. Approaches using cognitive therapy have also helped people reduce work pressure.

Suicide Risk

Some occupations—health professionals, financial service workers, and police, the first and latter groups because of easier access to lethal drugs and weapons—both attract persons with a high suicide risk and involve increased chronic distress that may lead to higher suicide rates.

Career and Job Problems of Women

Most women work outside the home out of necessity to support themselves or their dependents (whether children or adults) or as part of a working couple. With the divorce rate remaining at the 50 percent level, many women find themselves economically poorer after a divorce than when married, although divorced men usually find their economic status improved. Despite more than four decades of increasing knowledge about and concern for women’s status in the workplace, unique gender issues, bias, and lack of accommodation to their unique needs at certain life stages (i.e., pregnancy and postpartum, major responsibility for young healthy and ill children) continue. Yet, women were the largest group establishing new small businesses in the 1990s. Many have left large corporations where they were not valued for their efforts because of their gender. Women experience problems when they are the sole woman in a man’s field. Despite increasing recognition of the need for men in relationships with women to assume home and family responsibilities, fewer than 25 percent of men do so equitably.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree