Fig. 13.1

Note the ear protrusion, retroauricular edema, and redness in this patient with acute mastoiditis and subperiosteal abscess

As mentioned, the use of antibiotics in AOM does not appear to prevent complications. Anthonsen [6] reports that 35 % of children with AM were under antibiotics at the moment of the complication and there was no difference in the development of an abscess among children receiving or not the antibiotic (odds ratio 0.97). Similarly, Leskinen in Finland [13] reported that 55 % of children with AM were receiving antibiotics when admitted to hospital. They found no correlation between the prior intake of antibiotics and the percentage of mastoidectomies that had to be performed for AM. Other authors record that 85 % of patients were under antibiotic coverage [14].

The clinical evaluation of a child with an OMC should include an assessment of the general and neurological condition of the child, the presence of fever and lethargy, search for facial palsy, and signs suggesting an elevation of intracranial pressure. A thorough otomicroscopic exam should be done and, if possible, audiometry and tympanometry.

The bacteriology of AM is variable with the most frequent bacteria recovered being Streptococcus pneumoniae (25–51 %), S. pyogenes (2–26 %), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (4.5–29 %), Haemophilus influenzae (4.5–16 %), Staphylococcus aureus (3.5–8 %) and Fusobacterium necrophorum (5.8 %) [1, 8, 11, 15].

Radiological imaging in AM shows an occupation by secretions of the middle ear and mastoid cells associated with coalescence (Fig. 13.2). Some papers mention that routine computed tomography (CT) is not justified for AM [16], and that CT should only be done on the basis of the clinical presentation of each patient. Others do not agree [17], arguing that patients with AM and concomitant intracranial complications are often indistinguishable from noncomplicated AM patients. This makes CT a helpful tool in diagnosis, although there is no consensus in terms of whether it is mandatory in all cases of AM. Regardless, high-resolution temporal bone and brain CT carry a sensibility of 97 % and a positive predictive value of 94 % in the diagnosis of an intracranial complication of AM [18].

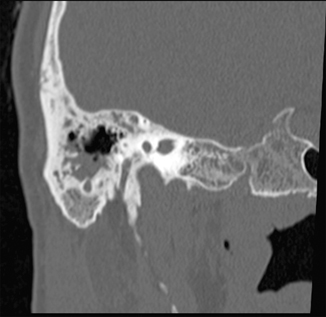

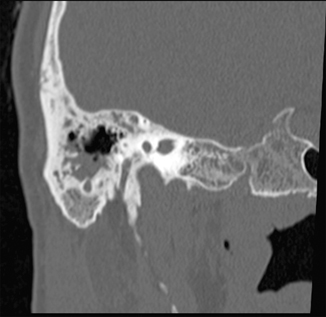

Fig. 13.2

Computed tomography showing occupation by secretions of the mastoid cells, associated to coalescent erosion of them

The prognosis of AM is closely linked to the presence of intracranial complications; hence, high clinical suspicion, early diagnosis, and appropriate treatment are necessary.

There are some controversies regarding the treatment of AM. For some groups, surgical treatment should be done upon AM diagnosis, with a simple mastoidectomy, for others management can be more conservative consisting of intravenous (IV) antibiotics or IV antibiotics and myringotomy with or without tube placement. Psarommatis [19] in a retrospective study of 155 patients with AM proposes an algorithm for its management. According to him, patients should be divided into three groups, one of patients with AM and suspicion of intracranial complication, another with isolated AM, and the third with AM and SA. According to his algorithm all the groups should be managed with myringotomy and IV antibiotics in the form of a third-generation cephalosporin (cefotaxime or ceftriaxone) and clindamycin. In patients with SA, a percutaneous drainage of it is done by aspiration or incision. If an intracranial complication is suspected, the radiologic evaluation is mandatory and if it is positive, a simple mastoidectomy should be done immediately. After initial management, all patients without a favorable response after 3–5 days should receive a simple mastoidectomy. Upon discharge, oral antibiotics should be prescribed for 7–10 days, with the exception of patients with intracranial complications that should receive oral antibiotics for at least 15 days.

Other authors recommend a similar management, proposing a more conservative treatment of noncomplicated AM following AOM, including IV antibiotics , myringotomy (with or without tympanosotomy tubes), and percutaneous drainage of possible SA [16, 20, 21] Groth reports that previous mastoidectomy seems to predispose the patient to recurrent AM. This could suggest a more conservative therapy [22].

In cases of AM in patients with COM with or without cholesteatoma, there is consensus that a mastoidectomy with removal of granulations and cholesteatoma should be done as soon as possible and antibiotics must include coverage for S. aureus and P. aeruginosa.

Facial Palsy

Facial palsy (FP) due to otitis remains infrequent, with a reported incidence of 0.005 % in AOM [23] and from 0.16 to 5.1 % in COM [24]. FP in AOM occurs usually after inflammation of the horizontal segment (tympanic) of the nerve, where it crosses the middle ear. In patients without chronic middle-ear disease, FP is usually secondary to neuropraxis from edema and nerve compression and/or bacterial toxic metabolites [25].

The House-Brackmann classification describes the degree of FP in each patient. There are six categories, I (normal function), II (mild paresis), III (moderate paresis), IV (moderate to severe paresis), V (severe paresis) and VI (complete palsy) [26].

CT scanning is indicated in patients that do not have a favorable evolution of FP or in cases in which there is a suspicion of a coexistent complication or in cases with a precedent of COM [24].

The use of magnetic resonance (MR) with gadolinium excludes other causes of FP. MR can show the inflammation of the nerve but does not determine the severity of the lesion [25].

Treatment includes wide-spectrum antibiotics with coverage for Streptococci, H. influenzae, and Staphylococci and tympanocentesis (for gram and culture) and myringotomy with tubes [27], although some authors recommend tubes only in cases with recurrent AOM or OME [25]. This conservative management in patients with less severe palsy (House–Brackmann II–III) is supported by the remission of symptoms in almost all the patients treated [23, 28]. Given the high rate of spontaneous recovery of FP, electrophysiological studies are not indicated for mild cases. In case of more severe FP (House–Brackmann IV–VI), electrophysiological tests, such as nervous excitability, maximal excitability electromyography, and electroneurography, can be helpful. The more severe degeneration of the nerve correlates with a bad recovery prognosis and may indicate surgical mastoidectomy with facial nerve decompression [25]. There is no consensus about the moment to perform surgery. Although some authors suggest it should be done during the acute phase, others suggest medical treatment and mastoidectomy should be performed and decompression should be postponed [29–31].

Complete facial palsy as a complication from AM or COM must be treated surgically. If it is due to an AM, mastoidectomy and myringotomy with a tube is suggested, if it is due to a COM, surgery must be done immediately, removing the cholesteatoma and granulation tissue [32, 33], as this situation may be associated to a poor prognosis [34].

Labyrinthitis

Labyrinthine infection results from extension of the infection from the middle-ear space to the cochlea and/or the vestibular system. Generally, the dissemination is via the round window, although it can also occur through the oval window, a perilymphatic fistula, or defects secondary to chronic infection with or without cholesteatoma, trauma, or postsurgical defects [25]. Labyrinthitis can be classified as serous and suppurative, with serous being far more frequent. It is produced by the action of toxins and inflammatory mediators without frank bacterial invasion into the inner ear. Cochlear involvement is more frequent than vestibular involvement. Labyrinthitis should be suspected in cases of AOM with sudden SNHL and/or vertigo [25]. If labyrinthitis occurs chronically in patients with COM, high-frequency SNHL is more likely, given usual greater damage of the basal turn of the cochlea [25].

Suppurative labyrinthitis is very infrequent, comprising approximately 2 % of the intratemporal complications of AOM [35]. It results from frank bacterial invasion into the inner ear and is highly suggestive of anatomical defects or immune deficiencies [25]. Clinical presentation is more severe, with high fever, vertigo, ear pain, nausea, vomiting, sweating, severe SNHL, and spontaneous nystagmus towards the unaffected ear. Any child with AOM and with nystagmus and vertigo should be treated aggressively because this suppurative labyrinthitis can progress to meningitis [25]. Although not mandatory for diagnosis, MR is the most sensitive imaging modality in the workup of labyrinthitis, showing an enhancement of the fluid in the labyrinth when gadolinium contrast is used. CT is only used as a presurgical study, looking for congenital anatomical anomalies, erosions, or cholesteatoma.

Treatment includes IV antibiotics with presumptive coverage for the most frequent pathogens in AOM (S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and M. catarrhalis), along with early myringotomy with or without tympanostomy tube placement . In cases of precedent COM, the antibiotic coverage should include S. aureus and P. aeruginosa coverage. In cases of coalescent mastoiditis, suppurative COM or cholesteatoma, a mastoidectomy with removal of the tissue is involved, and repair of an eventual perilymphatic fistula must be done [25]. Patients with serous labyrinthitis generally present a rapid resolution of vertigo and hearing loss although some deficit can persist. In case of patients with suppurative labyrinthitis and severe SNHL, recovery is very infrequent. Vertigo can last for weeks or months, until it is successfully compensated by contralateral ear and central mechanisms [25]. Ossificant labyrinthitis is a complication that can occur after acute labyrinthitis, where the labyrinth is replaced by fibrous and/or bony tissue, with a loss of its function. This is more frequent after meningitis and suppurative meningococcal labyrinthitis, but can also occur in cases of suppurative labyrinthitis without associated meningitis.

Petrositis

Petrositis results from the extension of the infection from the tympanic cavity towards the petrous apex air cells. It is very infrequent, and generally occurs along with intracranial complications of OM [35]. The classic clinical presentation of petrositis is called the Gradenigo’s triad: pain in trigeminal distribution, otorrhea, and VI nerve palsy. However, its presentation can be variable, the triad being present in only up to 40 % of patients [36]. An ear CT should be done if a destructive lesion of the petrous apex is suspected. If the lesion is confirmed, MR can give more information as well as show possible adjacent meningeal involvement. MR allows to differentiate among petrositis, cholesterol granuloma, cholesteatoma, and neoplasms (schwannoma, meningioma, condroma, or chordoma) [36].

Bacteria usually recovered are S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae y P. aeruginosa [11]. Reports consisting of small-patient series recommend early wide-spectrum IVs antibiotic treatment along with myringotomy with tympanostomy tube insertion and mastoidectomy in refractory cases or those secondary to COM [37–39].

Intracranial Complications

Since the introduction of antibiotics in the twentieth century, the incidence of intracranial complications due to OM significantly decreased from 2.3 %to 0.24–0.04 % [40]. Although IOMC are far less frequent than EOMC, they are much more dangerous, with a reported mortality of 16–18 % [40, 41]. Around half of the patients have more than one complication simultaneously [40]. Acute meningitis and cerebral abscess are the most frequent IOMC [40, 42, 43]. Microbiology of the abscess is variable and is related to the underlying etiology of the complication (AOM vs. COM). In abscess secondary to AOM, S. pneumoniae, S. pyogenes, S. aureus y H. influenzae are cultured, in patients due to COM, S. aureus, Proteus mirabilis, P. aeruginosa, Klebsiella spp., Enterococcus and anaerobes are found [43–45].

When an IOMC is suspected, imaging a study is mandatory. High-resolution brain CT with contrast along with temporal CT is excellent for the diagnosis of OMC [18]. However, there is consensus that in these patients a brain MR with venography should also be done in order to evaluate the possibility of sigmoid sinus thrombosis or petrositis [45–47].

Acute Meningitis

As mentioned before , acute otogenic meningitis and cerebral abscess are the most frequent IOMC. Kangsanarak reported 51 % of meningitis and 42 % of cerebral abscess in a group of 43 patients with IOMC [40], Penido in a group of 33 patients with IOMC reported 46 % of them presenting with cerebral abscess and 37 % presenting with meningitis [43]. Lumbar puncture is usually performed if an acute meningitis is suspected but it is important to remember that this has to be performed after scanning to rule out elevated intracranial pressure, which could result in cerebral herniation or coning along with mortality during lumbar puncture [43]. Broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics must be administered promptly along with myringotomy and ventilation tubes to obtain cultures and drainage of the middle ear. Mastoidectomy should be reserved for patients who do not respond to treatment within 48 h [48].

Intracranial Abscess

Otogenic intracranial abscess can be extradural, subdural, or parenchymatous. The most frequent locations are the temporal and cerebellar lobes [40, 41], with extradural ones being most frequent [44]. Although in adults these abscesses present in cases of underlying CSOM [40, 41, 49], in children these abscesses are more often seen in patients with AOM [42, 44]. They portend a high mortality rate (20–36 %), especially in developing countries [40]. However, more recent studies in developed countries report a low mortality [42, 44]. The most frequent symptoms are fever and ear pain followed by headache and otorrea [44]. Altered mental status is more frequent in patients with subdural and intraparenchymatous abscesses than in extradural ones. Nausea, vomiting, diplopia, seizures, limb paresis, and meningeal signs can be found [44].

Most of the authors agree that treatment should include long-term broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics with blood–brain barrier penetrance and the initial treatment should be modified and based on cultures and sensitivity as soon as possible. Several antibiotic treatments have been proposed, including combinations of third-generation cephalosporins , amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, ciprofloxacin, aminoglycosides, penicillin, vancomycin, metronidazole, chloramphenicol [40, 41, 45, 50], covering Gram positives, Gram negatives, S. aureus, anaerobic bacteria, and P. aeruginosa. Regarding the surgical treatment there are some controversies. The standard accepted treatment is abscess drainage through trephination or excision through craniotomy followed by a differed otologic surgery of mastoid drainage. However, some authors recommend other treatments, such as combined early neurosurgery and mastoidectomy, mastoidectomy with evacuation of the abscess through the mastoidectomy; some groups even perform only the mastoidectomy and reserve the neurosurgery only for selected cases. All of these treatments are supported by reports of low and comparable morbidities and mortalities that have decreased, towards 0 % [41, 43–45, 51–53]. Subdural abscess or empyema is an exception to this rule because it requires immediate neurosurgical drainage [41, 44, 50]. If the origin of the abscess is COM, mastoidectomy should be performed during the same hospitalization, either at the time of the neurosurgical procedure or after it. Mastoidectomy could be avoided only if the origin of the complication is AOM and if the patient has an excellent resolution with the initial treatment [43].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree