CHAPTER 12 Pain

The material in this chapter will help you to:

Introduction

Pain is a multifactorial experience with sensory and emotional aspects and it is best understood within a biopsychosocial framework. Although we now have a much better understanding of the neurobiological basis of pain, the lack of direct correlation between actual injury or pathology and reported pain and pain behaviour can only be understood when all aspects of the presentation are taken into account. Psychological and environmental factors can play a particularly important role in the transition from acute to chronic pain and its ongoing maintenance. Given that approximately one in five adults may suffer from chronic pain (Blyth et al 2001) and that biomedical interventions have limitations, understanding and managing all aspects of such a presentation is essential.

What is pain?

A comprehensive overview of the history of pain concepts and treatments can be found in Bonica and Loeser (2001). Here you will see that pain in different eras and different cultures has been viewed both as a sensation and thus tied to the stimulus (or injury) and as an experience with strong emotional features (e.g. a quality or passion of the soul or a form of punishment). The former view is more consistent with commonly held contemporary views of pain, especially in the Western world. However, for researchers and health professionals working in the area of pain, it has become increasingly obvious that pain is not adequately explained by linking it to a noxious stimulus. A brief paper by Wall and McMahon (1986) clearly outlines that the evidence of a relationship between perceived pain and the firing of specific types of nerve fibres, or nociception, is not simply variable but sometimes nonexistent. Melzack and Wall (1982) provide an excellent overview of the variability of this relationship, discussing a range of phenomena: for example, congenital analgesia (people who are born without the ability to feel pain and thus have no automatic warning system of injury), episodic analgesia (the inability to feel pain in certain situations such as when trying to survive on the battlefield), phantom limb pain (the experience of pain in a limb that does not exist) and, most commonly of all for many people in our society, the persistence of pain long after the healing of whatever injury was associated with its onset.

This more complex understanding of what pain is has led to the following definition of pain by the taxonomy committee of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) (1994): ‘[pain is] an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage’.

Biopsychosocial models of pain

A biopsychosocial model was discussed in Chapter 4. There it was pointed out that health or illness is influenced by a complex interplay of biological, psychological and social factors. In terms of understanding and providing a formulation of the experience of pain, a biopsychosocial model has been widely accepted by health professionals as providing the best possible template to assess and manage the presentation of pain. Given the IASP definition cited above that describes pain as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience, this of course makes perfect sense.

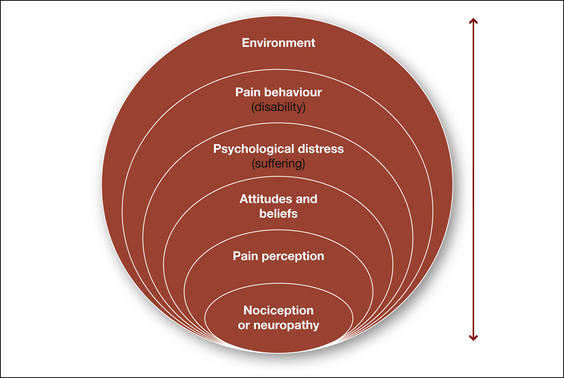

The biopsychosocial model originally delineated by Engel (1977) has been applied to pain by a number of important researchers in the field, including Fordyce (1976), Loeser (1982) and Waddell et al (1984). The broad components of the model are essentially the same in all versions and are elaborated in Figure 12.1. These components will be discussed in turn below but it is important to note that at all levels every component can impact on another level, in both directions. Thus changes at the physiological level initiated by trauma may have impact at the psychological and behavioural levels in terms of distress and/or avoidance of activity but equally changes at the psychological or behavioural level can, in turn, have impact at the physiological level, such as physical deconditioning (Turk & Flor 1999).

Nociception or neuropathy

Pain is universally viewed as a primary indicator of underlying tissue pathology and pain is also one of the main reasons that people visit health professionals (Coda & Bonica 2001). When considering the biological contributors to the experience of pain, we can divide pain into two types, depending on the structures and mechanisms involved. Nociceptive pain refers to pain arising from injury or pathology in the tissues, for example, soft tissue sprains and strains, bone fractures or appendicitis. Neuropathic pain, on the other hand, refers to pain arising from pathology to or changes within the peripheral and central nervous system. Nociceptive pain is generally described as aching or dull and, in the case of musculoskeletal pain, usually related to activity or posture. By contrast, neuropathic pain is frequently described as burning or shock-like and is associated with a region of sensory disturbance (Siddall in press). Episodes of neuropathic pain can occur spontaneously or as an exaggerated response to minor stimulation. An exaggerated response to a non-painful stimulus, such as light touch, is called allodynia. An exaggerated response to a painful stimulus is called hyperalgesia. Pain can further be classified clinically as acute or chronic. These distinctions are important as different types of pain, with different characteristics and underlying mechanisms, have different responses to treatment.

Table 12.1 Differentiating nociceptive pain from neuropathic pain

| NOCICEPTIVE PAIN | NEUROPATHIC PAIN | |

|---|---|---|

| Biological basis | Damage and/or disease in somatic and visceral structures such as bone fractures, ligament sprains, appendicitis | Damage and/or disease in peripheral or central neural structures such as peripheral nerve injury, postherpetic neuralgia (shingles), spinal cord injury pain |

| Symptoms | ||

| Signs |

PAIN PROCESSING IN THE PERIPHERAL AND CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM

Understanding the nature of pain has consumed humankind throughout the ages. During the 19th and 20th centuries, advances in the study of anatomy, physiology and histology prompted the formulation of several physiologic theories of pain. Of these, the gate control theory (Melzack & Wall 1965) was the most influential and the first attempt to combine neurophysiological mechanisms with psychological processes such as cognitions and emotions. In this model, pain was viewed as an end product of a number of interacting processes in which the central nervous system played an active role in determining the nature and degree of pain following harmful stimulation in the periphery. Although we now know that this theory is overly simplistic, it nevertheless provides us with an understanding of the types of mechanisms involved in the processing and modulation of the experience of pain.

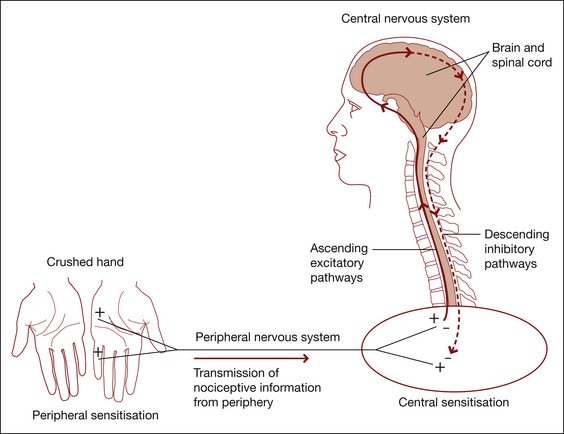

Under normal conditions central sensitisation resolves following recovery. In some cases, however, central changes persist and symptoms associated with these changes are seen in pathological pain states such as complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), failed back surgery syndrome and phantom limb pain.

From the spinal cord, noxious signals reach the brain via a number of ascending tracts that terminate in many structures throughout the brainstem, thalamus and cortex (Fields 2004). The thalamus acts as a major relay station in the transmission of noxious signals. As these signals reach the brain, many other regions are also activated, including those that control a number of autonomic and homeostatic mechanisms such as blood pressure regulation and respiration (Siddall & Cousins 2004). In addition, there are descending mechanisms mediated by a variety of neurotransmitters, acting at subcortical and spinal cord levels, modulating ascending information (Fields 2004).

The higher brain centres used in pain processing can be divided into those involved in the sensory-discriminative component of pain perception (somatosensory cortex) and the affective component of pain perception (such as cingulate cortex). However, this may be an oversimplification. Functional imaging studies have now identified a widely distributed network of cortical and subcortical areas that are activated by noxious stimuli (Ingvar 1999). These include sensory, limbic, associative and motor areas. Functional imaging studies have also shown significant differences in brain activation between people with no pain, acute pain and chronic pain (Apkarian et al 2005). Figure 12.2 shows the mechanisms of pain.

Pain perception

Pain does not occur in isolation but, rather, within a context that has a direct bearing on the person’s perception of pain and on their response to pain (Siddall in press). Pain can be extremely variable; it can attain intolerable intensity, persist beyond tissue healing or disappear in the heat of battle. The way we interact with our environment is significantly affected by pain. Our behaviour also changes over time as the pain state continues.

Given the IASP definition of pain as an experience that is modulated by a complex set of emotional, environmental and psychophysiological variables, one would expect that pain would influence brain processing on many levels (Ingvar 1999). The neural representations of the mechanisms involved in pain modulation – for instance, the influence of learning, meaning, attention, anticipation or avoidance – should also be taken into account when one considers the representation of pain at the neural level.

A number of research techniques have been used to study these neural representations:

In recent years, functional imaging has added significantly to our knowledge of where and how pain is processed in the brain (Bushnell 2005). As pointed out earlier, the processing of pain can no longer be viewed as a simple ‘hard-wired’ system with a strong relationship between stimulus and response (Siddall & Cousins 1997). We now have a better understanding of the neuroplastic changes that occur within the central nervous system in the presence of pain and hence the changes that should be addressed as part of an integrative approach to pain management (Siddall in press).

Attitudes and beliefs

What the pain means to a particular person at a particular time will have a clear influence on how that person subsequently responds. For example, if a person wakes in the night with stomach pain, he or she may think ‘I should not have eaten so much’, groan, roll over and eventually fall back to sleep. However, if they think that the pain may be an indicator of stomach cancer, perhaps because they saw a program on television about stomach cancer the previous evening or because they have a close relative with that disease, they are then likely to begin monitoring the pain, become worried and distressed, be unable to fall back to sleep and so on. Chapman and Okifuji (2004) discuss three main cognitive factors that will influence the pain experience:

Chapman and Okifuji (2004) point out that studies have shown all three factors to have an impact at the physiological level. For example, skin conductance in headache patients is elevated in response to seeing words relating to migraines on a screen (Jamner & Tursky 1987).

Psychological distress (suffering)

For many people pain, by definition, entails suffering. Nevertheless the degree of suffering is clearly variable and likely to be influenced by a range of factors. For example, the duration, severity, frequency and number of sites of pain (Fishbain et al 1997) may impact on the level of suffering. Williams (1998) points out that a person in pain may experience a wide range of losses both material and intangible, covering everything from employment and finances, to changes in relationships, being able to maintain independence, issues of self-worth and so on. They also often experience symptoms such as fatigue, difficulty concentrating, muscle tension, disturbed sleep, side effects of medication and deconditioning. In addition they may have to deal with a range of health professionals, with possible disbelief and lack of understanding from some and undergo a variety of tests and interventions. They may have numerous fears or worries, including fear about the cause of the pain or that the doctors have missed something, fear of re-injury, worries about the future, financial concerns and so on.

Given all the issues faced by people with persistent pain it is not surprising that a large proportion may be diagnosed as having depression or an anxiety disorder. Although issues of measurement and definition make establishing prevalences difficult (Williams 1998), few would dispute that it is a major issue for a large number of such people. Studies in the area of depression suggest a wide range of prevalences ranging from 10 to as high as 100% but with the majority reporting it in over 50% of cases (Sullivan 2001).

There has been much debate about the relationship between depression and chronic pain, particularly regarding the question of whether pain causes depression or depression leads to pain (Fishbain et al 1997). A comprehensive review of the literature on the pain–depression association by Fishbain found little evidence for the hypothesis that depression leads to pain while all studies relating to the hypothesis that pain can lead to depression had results consistent with that hypothesis. In addition, increased pain led to increased depression rather than the other way around. Having said that, it would of course always be important to establish if there is any history of depression or other psychiatric illness.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and chronic pain can share a specific relationship in that very often the accident or trauma that occasioned the ongoing pain has also caused post-traumatic stress symptoms (see Sharp & Harvey 2001). For example, as a result of a motor vehicle accident, a person may experience pain from physical injuries and post-traumatic stress symptoms relating to the accident. Not surprisingly, as with depression, having PTSD and chronic pain means an additional load and likely interactions for the patient. This means both must be addressed.

FEAR AVOIDANCE

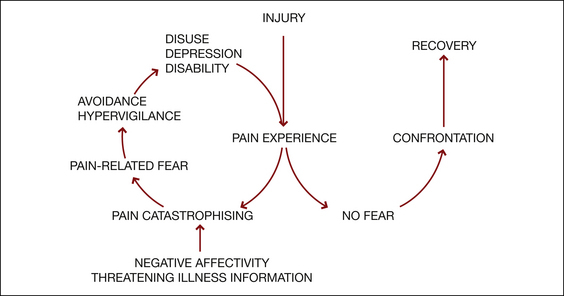

People in pain can evidence a high level of ‘fear avoidance’, such that they become fearful of engaging in physical activity due to the risk of increased pain and/or (re)injury and therefore avoid the activity (see Fig 12.3) (Vlaeyen et al 1995, Vlaeyen & Linton 2000). Over time this can result in significantly reduced activity levels, increased disability, deconditioning and depression or distress. Fear avoidance provides an excellent example of the interaction of three separate levels of the biopsychosocial model. Beliefs or appraisals of pain at one level result in anxiety or fear at the next level that, in turn, results in disability or pain behaviours at the next. The latter then further entrench the negative aspects of the pain experience and thus fear avoidance becomes established. Leeuw et al (2007) recently published a comprehensive review of the current evidence for the fear-avoidance model.

Pain behaviour

As pointed out by Fordyce (1976), the only way in which we can know that a person is in pain is by their display of pain behaviour; by observing what they do or do not do and what they tell us. There is no objective measure of pain available to us other than this. Moreover, as pointed out earlier in the chapter, there is often no correlation between what we observe in this regard and identifiable tissue damage. Pain behaviours can take many forms from grunting, moaning and groaning, to limping, distorted posture and being hunched over. People may tell you that they are in pain but equally their lack of social engagement may be an indicator of discomfort. They may take medication, attend numerous medical appointments or treatments and they may take time off work, lie down or cease activities. Equally they may rate their pain as being very high on questionnaires or in response to questions about their pain. It is important to note in relation to pain behaviours that, because pain is a completely subjective experience and because there are no objective measures, health professionals can only go by the person’s report. A change in such behaviours and reports can at least indicate that, for that person, at that time, there has been a change in their experience of the pain. Note also, suggesting to a person that they are not in pain may only serve to increase the display of pain behaviour. The important point here is that if pain is viewed as an experience, the distinction between real, exaggerated or fabricated pain becomes irrelevant. For health professionals the targets of treatment become not the pain itself but the associated suffering or disability (Fordyce 1988).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree