FIGURE 10-1 Potential pain perception can be studied in patients with disorders of consciousness during resting state, in the absence of external stimulation. Here, the level of consciousness in noncommunicating patients in minimally conscious state (MCS), vegetative state/unresponsive wakefulness syndrome (VS/UWS), and coma positively correlated with functional connectivity in the anterior cingulate cortex of the salience network, which has been implicated in the attentional and emotional aspects of pain. Although the subjective-emotional counterpart cannot be directly measured with this approach, these results could account for the preserved capacities of some patients to orient their attentional resources toward environmental salient stimuli, such as noxious stimulation. (Adapted from Demertzi et al. [12].)

BEHAVIORAL ASSESSMENT OF PAIN IN DISORDER OF CONSCIOUSNESS

Several scales have been developed and validated to detect pain in noncommunicating patients, such as newborns, patients with dementia (see Chapter 12), and sedated/intubated patients. For example, the COMFORT scale has been developed for use in young sedated patients between 0 and 3 years old [63]. It includes the observation of respiratory and motor responses, cardiac frequency, blood pressure, facial expression, agitation, and level of awakening. Each parameter is scored from 1 to 5. The total score ranges from 8 to 40, with a score between 17 and 26 indicating appropriate sedation level. To our knowledge, this is currently the sole scale that assesses oversedation, comfort, and distress in newborns and young children in intensive care. The Behavioral Pain Scale (BPS [47]) and the Critical Care Pain Observation Tool (CCPOT [22]) have been developed for noncommunicating and sedated adult patients in intensive care. The BPS assesses facial expression, movements of the upper limbs, and the compliance to mechanical ventilation in intubated adults. Each parameter is scored from 1 to 4. The total score ranges from 4 to 12. The CCPOT includes the facial expression, body movements, muscle tension, and compliance with the ventilator/vocalization. Its total score ranges from 0 to 8. Several studies have shown the reliability and validity of these scales for use in intensive care adult patients [3, 53]. Additionally, a recent study also suggested that the CCPOT would be more sensitive to pain than the BPS when comparing score changes between a nonpainful and a painful condition [53]. Recently, a new scale has also been proposed for ventilated critically ill and noncommunicating patients, the scale of behavior indicators of pain (Escala de Conductas Indicadoras de Dolor: ESCID). A good concurrent validity with the BPS and a good internal consistency of the scale were reported in a previous study [36].

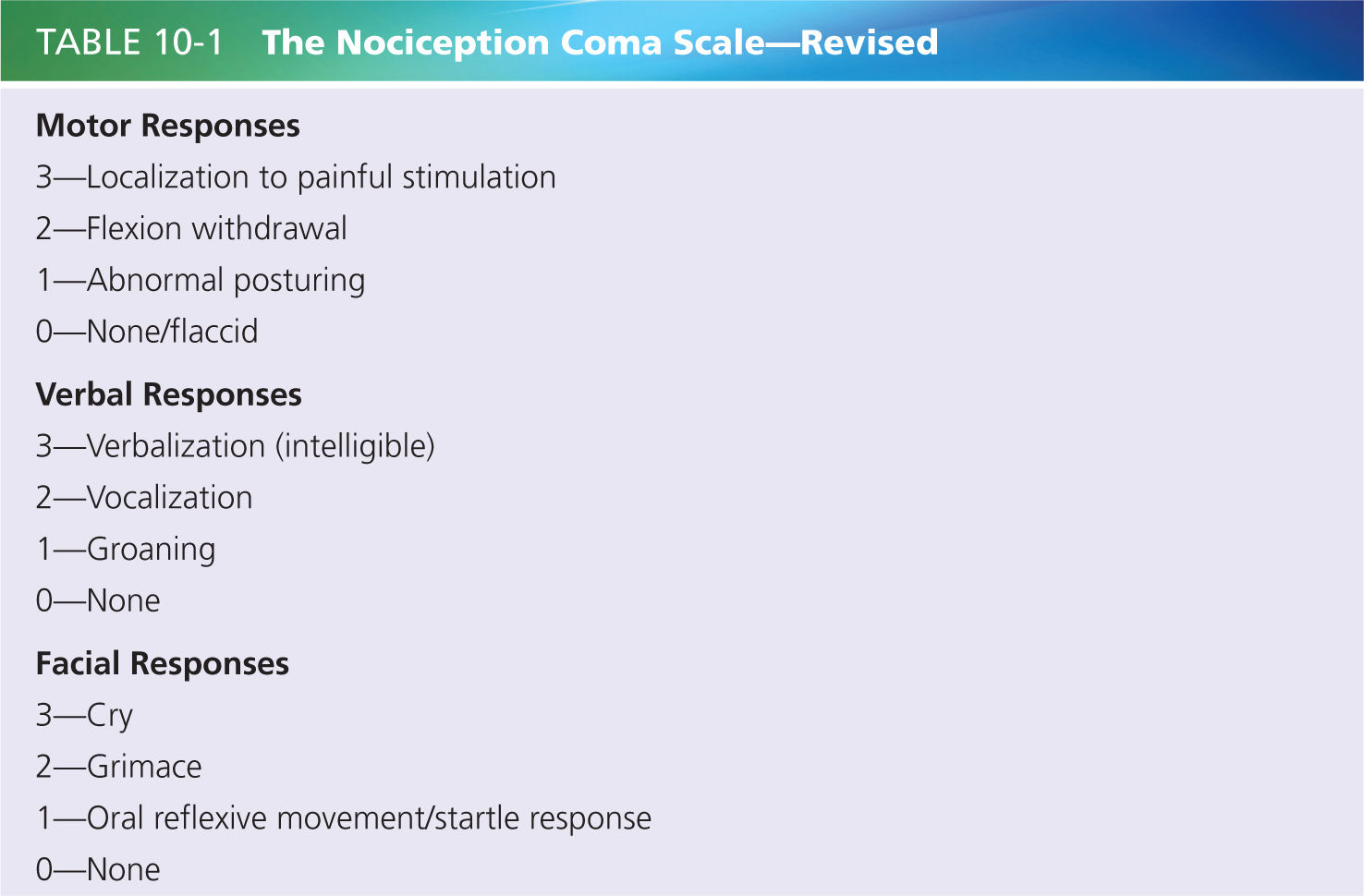

Nevertheless, only a few scales have been developed to assess pain in patients with DOC until recently [57]. Among them, the Nociception Coma Scale (NCS [57]) was developed in 2010 to specifically assess nociception and pain in patients with DOC in acute and chronic setting. The NCS is based on preexisting pain scales validated in noncommunicating patients with advanced dementia and newborns. The first version of the scale consisted of four subscales assessing motor, verbal, visual responses, and facial expression. Initially, breathing responses were also assessed but later discarded due to the difficulty to objectively assess breathing patterns in patients not benefiting from respiratory monitoring devices [56]. In addition, previous studies have shown that physiological parameters seem insufficiently sensitive for pain assessment [21, 26]. Stress, medication, medical complications, and brain lesions affecting autonomic functions can influence these parameters and bias the assessment as well.

A first study including 48 patients from intensive care, neurology/neurosurgery units, rehabilitation centers, and nursing homes reported a good interrater reliability and good concurrent validity for the NCS total scores and subscores when compared to other scale developed for noncommunicating patients (e.g., the neonatal infant pain scale [39], the pain assessment in advanced dementia scale [65]). A second study on 64 patients investigated the sensitivity of the NCS by comparing NCS scores observed at rest, in response to a non-noxious stimulus (i.e., tap on the shoulders) and a noxious stimulus (i.e., nail bed pressure [9]). Results showed that NCS total scores as well as motor, verbal, and facial subscores were significantly higher in response to a noxious stimulus than at rest or in response to a non-noxious stimulus, reflecting the good sensitivity of the scale. However, no difference could be observed between noxious and non-noxious conditions for the visual subscores, suggesting that this subscale was not specific to nociception. A modified version of the scale excluding the visual subscale, the Nociception Coma Scale—revised (NCS-R, see Table 10-1) [9], was therefore proposed.

The NCS-R is meant to be administered in all patients who are in a VS/UWS or in a MCS, especially those who present a documented potential pain (e.g., polytraumatic injuries, decubitus ulcers, severe spasticity, wounds, or arthralgia). A particular attention should be given to patients with spasticity as it is a frequent condition in chronic DOC. Indeed, a recent study showed that 89% (58/65) of patients who were in a chronic DOC demonstrated signs of spasticity (modified Ashworth Scale, MAS ≥ 1), including 60% (39/65) qualified with severe spasticity (MAS ≥ 3). In addition, the severity of spasticity was correlated to NCS-R scores (i.e., likely to reflect nociception or pain), highlighting the importance of pain management in noncommunicating patients after severe brain injury [62].

Any information about preexisting pain (e.g., osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis) is helpful before starting using the scale. The NCS-R should be scored at rest and during cares in order to observe the spontaneous responses presented by the patient (preferably assessed with eyes opened) before the potentially painful care and/or stimulating a potentially painful area. Behavioral responses observed before and during the care and/or stimulation will be scored according to the NCS-R guidelines. Spontaneous behaviors at rest can also be taken into considerations. However, these responses could be unrelated to pain (e.g., pathologic activation of subcortical areas leading to constant but not appropriate cries [45]) and should therefore be replicated in a pain-related condition (i.e., mobilization/palpation). The highest scores obtained for each subscale are summed to obtain a total score ranging from 0 to 9. In case of a documented cause of potential pain, the NCS-R should be administered before and after analgesic treatment.

It is essential to assess simultaneously the patient’s level of consciousness in order to avoid overmedication. Indeed, it is likely that the administration of sedating analgesics will decrease the presence of pain behaviors but also the patient’s responsiveness as those medications may have an impact on alertness and vigilance in patients with severe brain injury. On the other hand, the presence of untreated pain could reduce already limited attentional resources, and prevent the patient from interacting with his or her surroundings and showing sign of consciousness. Indeed, a recent study reported an improvement of consciousness when administering analgesic treatment to a brain-injured patient suffering from severe spasticity [62]. A good balance remains therefore to be found between undertreatment and overtreatment by revising pain treatment regularly. Considerations should be given to nonsedating medications or to medications with reversible effects whenever there is question of medication effects versus ongoing deterioration of neurological status.

In this context, the NCS-R may constitute a helpful instrument for monitoring pain behavior on a daily basis. In the absence of documented conditions likely to produce pain, a sudden increase of the NCS-R total score independent from an improvement in the level of consciousness can alert the clinician of the potential presence of pain/underlying medical complication. Additional investigations may then be performed to identify its origin/localization (e.g., by using mobilization/palpation/CT scan).

In a recent study looking at the clinical validity of the scale, 39 patients with potentially painful conditions (e.g., due to fractures or spasticity) were assessed during nursing cares before and after the administration of an analgesic treatment tailored to each patient’s clinical status [8]. The Glasgow coma scale (GCS) was also used before and during treatment in order to observe fluctuations in consciousness. A decrease in the NCS-R total scores and subscores was reported during treatment when compared to the scores observed before treatment. Interestingly, no difference between the GCS total scores obtained before versus during treatment was observed suggesting a good balance between decrease in pain and preserved level of consciousness. More precisely, 20 patients showed a decrease in the NCS-R scores with no decrease of the level of consciousness (i.e., GCS scores). Finally, 5 of these 20 patients showed higher signs of consciousness (i.e., increase in GCS scores) following the analgesic treatment as compared with before, suggesting that the presence of pain may have compromised the ability of the patient to respond at bedside (also see reference [62]). The fact that 59% of the patients included in the study (23 of 39) did not have any analgesic treatment prior to the assessment also underlines the crucial need for an appropriate management of pain in this population.

The COMFORT, the BPS, the CCPOT, and the ESCID were first developed for patients in the acute setting (including sedation and ventilation), and all of the scales presented here include observation of the motor response and facial expression. However, studies quantifying facial expression (i.e., grimace) in patients with DOC are currently lacking. This is even more of a problem in case of severe spasticity [62] or oral response limited by trachea/anarthria, where the use of motor or verbal responses may be limited and facial expression is sometimes the only remaining communicative means that can be used in this population. Even if grimacing is considered as an indicator of pain, the Multi-Society Task Force on PVS did not consider it as a necessary sign of conscious perception as they can occur reflexively through subcortical pathways in the thalamus and limbic system [45]. Patients showing no sign of consciousness except grimaces to nociceptive stimuli can therefore be diagnosed as being in VS/UWS. Nevertheless, very few studies have investigated such behavior in conscious (MCS) versus nonconscious (VS/UWS) patients. Recently, Schnakers et al. [55] investigated the frequency of grimace in DOC. They reported that grimaces were more frequently displayed in response to nociceptive stimuli than in response to non-nociceptive stimuli in both MCS and VS/UWS patients (i.e., 48% vs. 4% for VS/UWS and 65% vs. 3% for MCS, respectively). However, grimace to pain was not observed more frequently in MCS than in VS/UWS patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree