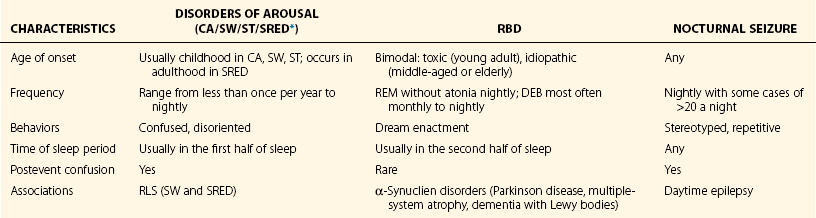

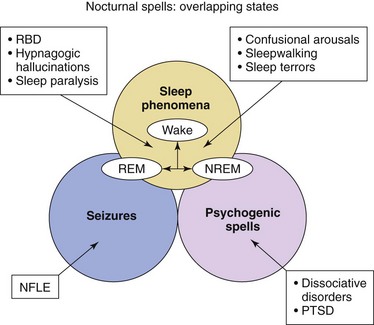

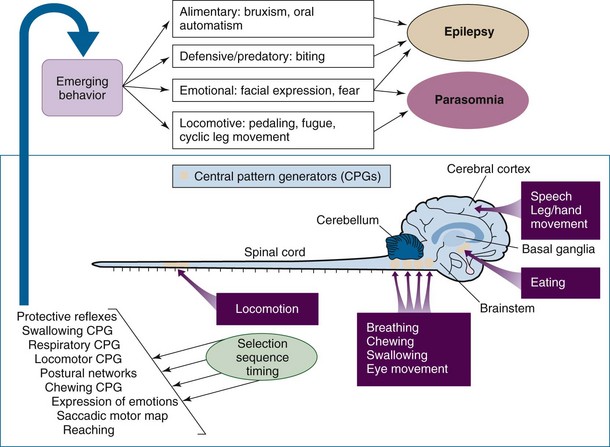

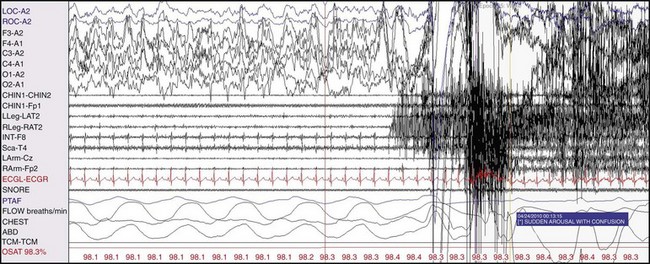

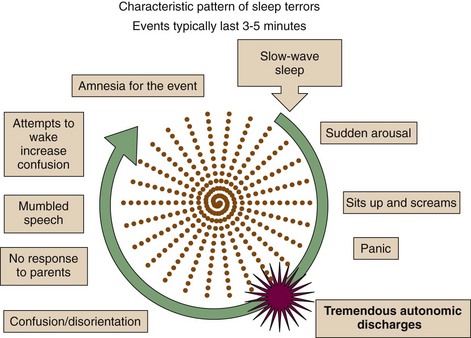

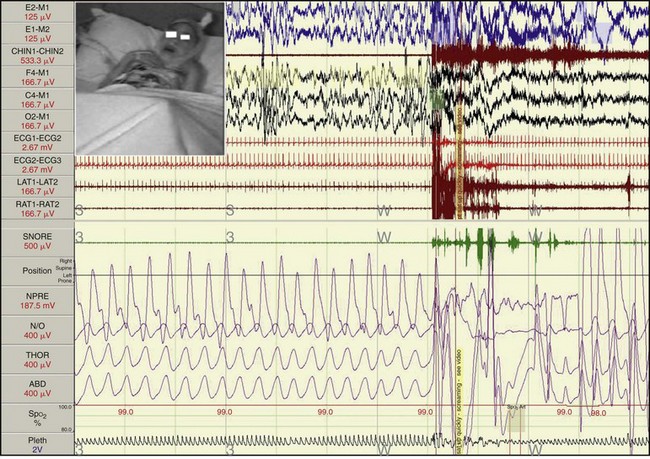

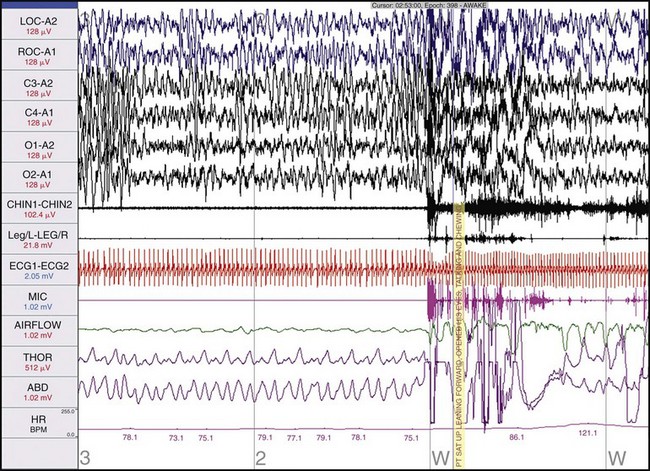

Chapter 12 Parasomnias are abnormal physical and experiential phenomena that arise from the sleep period. Disorders of arousal, such as sleepwalking, result from an incomplete dissociation of wakefulness from non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. Conditions that provoke repeated cortical arousals or that promote sleep inertia lead to NREM parasomnias by impairing normal arousal mechanisms. Sleep-related eating disorder (SRED) is characterized by a disruption of the nocturnal fast with episodes of feeding after an arousal from sleep. NREM parasomnias are often associated with the use of sedative hypnotic medications, in particular the widely prescribed benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BRAs). Recently, evidence suggests that many cases of sleepwalking and SRED are induced when BRAs are mistakenly prescribed to patients with restless legs syndrome (RLS). REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is characterized by a loss of skeletal muscle paralysis during REM sleep that leads to potentially injurious dream enactment. The loss of REM atonia in RBD is often a cardinal finding in the development of α-synuclein neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson disease. Epilepsy with motor seizures may be limited to the nocturnal period and may thus be confused with disorders of arousal and RBD. Other parasomnias include experiential phenomena, such as “exploding head” syndrome and sleep-related hallucinations (see Table 12-1 and Box 12-1). The current understanding of the underlying pathophysiology of parasomnias is based on the understanding that sleep and wakefulness are not mutually exclusive states of being. As one falls asleep and advances through the various sleep stages, the sleep stage shifts are not complete “on or off” switch phenomena, but rather involve transitions of several neuronal centers for an equivocal stage to declare itself. It is during this period of sleep-wake dissociation that a person can encounter an admixture of different states of being. They may overlap or intrude into one another and result in complex behaviors (Fig. 12-1). Figure 12-1 Overlapping states of being, as described by Mahowald and Schenck. Another hypothesis is that central pattern generators (CPGs), as illustrated in Figure 12-2, lead to deafferentation of the locomotor centers from the generators of the different sleep states. Locomotor centers are present at both spinal and supraspinal levels, and this dissociation can explain motor activity or ambulation, especially in patients with disorders of arousals. Figure 12-2 Along all levels of the neuraxis that stem from the brain to the upper brainstem and spinal cord, several neuronal networks exist that produce different types of behavior (upper panel) when activated. The disorders of arousal vary across a spectrum of duration, autonomic activity, and arousal threshold. Confusional arousals are characterized by disoriented behavior limited to the sleeping area with subsequent impaired recall of events (see Figs. 12-3 and 12-4 and Video 12-1). In adults, they can sometimes be triggered by a comorbid sleep disorder such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA, Fig. 12-5). Sleepwalking is a combination of ambulation with impaired consciousness (Figs. 12-6 and 12-7). Sleep terrors usually occur in preadolescent children, involve episodes of intense fear initiated by a sudden loud vocalization, and are accompanied by precipitously increased autonomic nervous system activity (Figs. 12-8 through 12-10). Patients with sleep terrors are typically inconsolable. The major differences between sleep terrors and REM nightmares are shown in Table 12-2. Table 12-2 Differences Between Sleep Terrors and Nightmares Figure 12-3 Spontaneous confusional arousal. Figure 12-4 Hypnogram with multiple confusional arousals (CA). Figure 12-5 Polysomnogram (120-second epoch) from a 54-year-old man conducted to evaluate for arousals with confusion and singing behavior. Figure 12-6 Sleepwalking with restless legs syndrome (RLS) and periodic limb movement disorder. Figure 12-7 Sleepwalking with obstructive sleep apnea. Figure 12-8 Characteristic pattern of sleep terror. Figure 12-9 Two-minute epoch of a diagnostic polysomnogram from a 9-year-old boy performed to evaluate for arousals associated with screaming and inconsolable crying. Figure 12-10 Sleep terror. Comorbid conditions that promote sleep inertia or fragmented sleep lead to incomplete cortical arousal. Phenomena that deepen sleep, such as sleep deprivation and sedative medications, promote NREM parasomnias by impairing arousal mechanisms (Clinical Case 12-1). Conditions that cause repeated cortical arousals, such as sleep-disordered breathing (see Fig. 12-5) or noise, lead to parasomnias through increased sleep fragmentation. The isolated activation of functional groups of motor neurons with a relative paucity of activity in brain regions that control executive function and memory account for the poor judgment and amnesia that characterize NREM parasomnias.

Parasomnias

Overview

Pathophysiology of Parasomnias

Parasomnias are explainable by the basic notion that sleep and wakefulness are not mutually exclusive states; these may dissociate and oscillate rapidly. The abnormal admixture of the three states of being—non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, REM sleep, and wakefulness—may overlap and give rise to parasomnias. REM parasomnias occur as a result of the abnormal intrusion of wakefulness into REM sleep; likewise, NREM parasomnias, such as sleepwalking, occur because of abnormal intrusions of wakefulness into NREM sleep. Other nocturnal spells that may be confused with parasomnias include nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy (NFLE) and psychogenic spells such as those associated with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and dissociated disorders. RBD, REM sleep behavior disorder. (Modified from Mahowald MW, Schenck CH: Non–rapid eye movement sleep parasomnias. Neurol Clin 2005;23[4]:1077-1106, vii; and Avidan AY, Kaplish N: The parasomnias: epidemiology, clinical features, and diagnostic approach. Clin Chest Med 2010;31[2]:353-370.)

The networks are collectively referred to as central pattern generators (CPGs), depicted as the tan regions in the bottom panel. The spectrum of resulting behaviors may be simple and stereotyped, such as rhythmic lip smacking and swallowing, to the more polymorphic and complex, such as those generating locomotion and search behaviors. The CPGs are thought to lead to monomorphic spells, which are stereotyped behaviors (automatisms) in which the possible etiology could be related to nocturnal seizures or highly complex (locomotive) polymorphic behavior, in which the cause may be a parasomnia. (Modified from Grillner S: The motor infrastructure: from ion channels to neuronal networks. Nat Rev Neurosci 2003;4:573-586; and Tassinari CA, Cantalupo G, Högl B, et al: Neuroethological approach to frontolimbic epileptic seizures and parasomnias: the same central pattern generators for the same behaviours. Rev Neurol [Paris] 2009;165:762-768.)

Disorders of Arousal: Non–Rapid Eye Movement Parasomnias

CHARACTERISTIC

SLEEP TERROR

NIGHTMARE

Timing during the night

First third (deep slow-wave sleep)

Last third (REM sleep)

Movements

Common

Rare

Severity

Severe

Mild

Vocalizations

Common

Rare

Autonomic discharge

Severe and intense

Mild

Amnesia

Absent

Present

State on waking

Confused, disoriented

Lucid

Injuries

Common

Rare

Violence

Common

Rare

Displacement from bed

Common

Very rare

This 30-second polysomnograph demonstrates a sudden arousal in a 39-year-old woman with a history of non–rapid eye movement parasomnias unprecipitated by a respiratory event. She subsequently sat up, verbally berated her husband (who was not present), and attempted to remove her electroencephalogram wires.

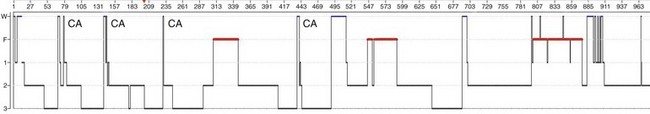

Notice that several confusional arousals emanated from slow-wave sleep during the first half of the night.

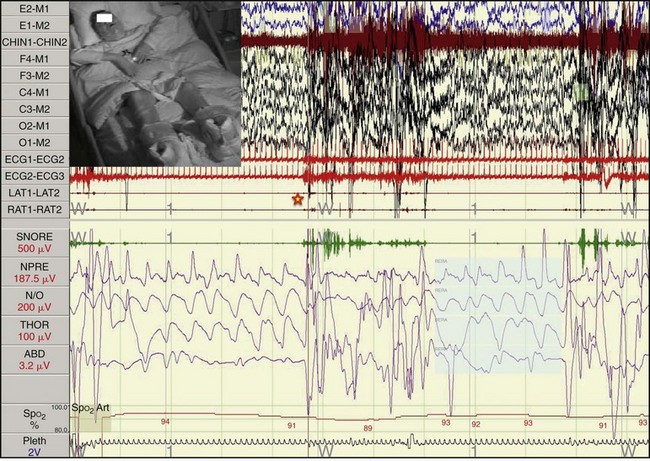

The figure illustrates one of the patient’s representative events, an arousal from slow-wave sleep, as demarcated by the star, with the patient’s arms abducted (flapping his arms and described by the technicians to be “quacking like a duck”). (Modified from Avidan AY, Kaplish N: The parasomnias: epidemiology, clinical features, and diagnostic approach. Clin Chest Med 2010;31[2]:353-370.)

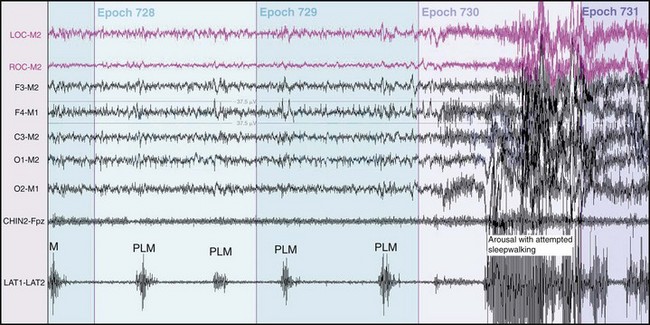

This 2-minute polysomnogram demonstrates an arousal with attempted sleepwalking preceded by frequent periodic limb movements. The 28-year-old woman also described wakeful motor restlessness consistent with RLS. Dopaminergic therapy resolved the RLS symptoms and sleepwalking episodes.

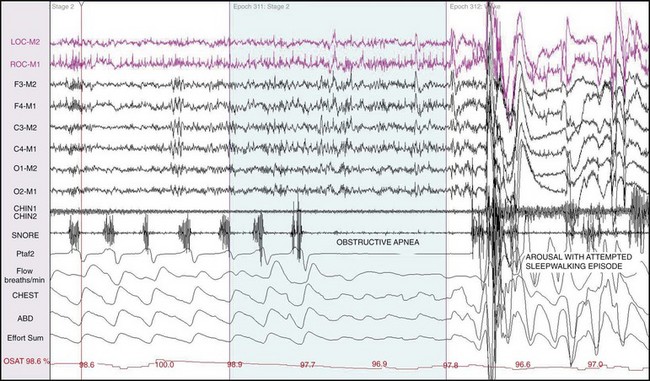

This 90-second polysomnogram demonstrates an arousal with an attempted sleepwalking episode after an obstructive apnea in a 40-year-old man.

Sleep terrors are characterized by a sudden arousal associated with a scream, agitation, panic, and heighted autonomic activity. Inconsolability is almost universal. The child is incoherent and has altered perception of the environment, appearing confused. This behavior may be potentially dangerous and could result in injury. (Modified from Avidan AY, Kaplish N: The parasomnias: epidemiology, clinical features, and diagnostic approach. Clin Chest Med 2010;31[2]:353-370.)

The figure illustrates one of the patient’s representative spells, illustrating an arousal with screaming arising out of slow-wave sleep with the patient’s arms flexed and held close to the chest, as if afraid and protecting himself. (Modified from Avidan AY, Kaplish N: The parasomnias: epidemiology, clinical features, and diagnostic approach. Clin Chest Med 2010;31[2]:353-370; polysomnogram courtesy Timothy Hoban, MD, University of Michigan–Ann Arbor.)

This 90-second polysomnogram shows an arousal from non–rapid eye movement sleep in a patient with sleep terrors. Such arousals typically arise from slow-wave sleep, as in this case. Note the precipitous nature of the arousal and the increase in heart rate.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree