The sleep-wake transition disorders are benign, very common events that occur during the transition from wake to sleep state or vice versa; they may be regarded as normal phenomena and are usually present in otherwise healthy populations. Occasionally, these events may occur frequently enough to cause disruption of the normal sleep cycle and may create discomfort or be associated with injuries or anxiety. Mild cases are usually untreated; however, severe cases may warrant treatment. They are more common in young children (6 months to 4 years) and males (about four times), and usually resolve spontaneously.

There are four different sleep-wake transition disorders: rhythmic movement disorder, sleep start, sleep talking, and nocturnal leg cramps.

Rhythmic Movement Disorder

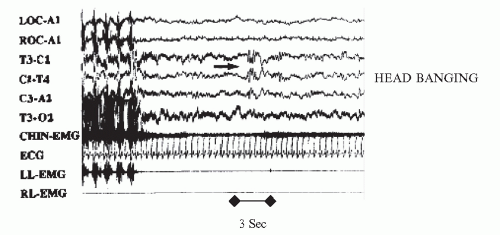

Also called stereotypic movement disorder, this a disorder typically found in children. It is characterized by rhythmic

movements in the head and neck or large muscle groups, occurring with a frequency of 0.5 to 2 Hz, which can persist for a few minutes to many hours and may occur almost nightly. They may appear in all sleep stages, but tend to be more common during sleep stages 1 and 2 (see

Fig. 16-1). Head banging (jactatio capitis nocturna) typically occurs with the patient in supine position and is characterized by anteroposterior head movements.

This disorder is called head banging because frequently the child bangs his head against the pillow or the headboard. Body rocking movements are associated with anteroposterior body movements occurring in different body positions. Other movement includes rocking on hands and knees. These movements may result in soft tissue injury and, rarely, eye trauma, hemoglobinuria, internal carotid artery dissection, and subdural hemorrhage. Rhythmic activity during sleep is seen in up to 67% of normal infants and decreases to 6% by the age of 5 years. The average onset is 9 months and commonly subsides before 10 years of age. Patients with mental retardation or autism persist longer, but up to 20% of normal children persist with rhythmic movements after 10 years of age.

The pathophysiology is unknown. It has been hypothesized that the rocking movements help development of the vestibulo-ocular and vestibulospinal reflexes to improve overall motor development. Diagnosis of rhythmic movement disorder by history alone is difficult since the clinical description is similar to other sleep disorders, seizures, or psychogenic events. Even with video electroencephalographic monitoring, frontal lobe seizures may be hard to differentiate since they frequently have multiple movement artifacts that obscure the electroencephalogram(EEG). A combination of clinical features and video EEG monitoring or polysomnography (PSG) offers the best diagnostic yield (see

Fig. 16-1). Differential diagnosis includes seizures, tantrums, and night terrors (

7,

8).

Often there is no need for treatment other than reassurance. Frequently, there is spontaneous resolution as

children get older. Benzodiazepines and tricyclic antidepressants have been used with variable success. Behavior modification has had little success. Protection of the sleep environment is essential to prevent injuries.

Nocturnal Leg Cramps

Nocturnal leg cramps occur spontaneously during sleep, typically in the calf. No particular sleep state has been associated with this disorder. The pathophysiology is unknown and lasts up to 30 minutes. Cramps may be precipitated by changes in water and electrolyte homoeostasis or by drugs, such as diuretics, laxatives, beta2 agonists, cimetidine, and phenothiazines. The cramp frequency varies from sporadic to daily occurrences. Sleep is disrupted by this sudden painful cramp (

9).

Treatment is recommended according to the frequency and severity of events. Multiple treatments are available (

Table 16-3). Quinine can effectively prevent nocturnal leg cramps, however, it is also associated with significant side effects. Calcium-channel blockers have been effective, particularly verapamil and diltiazem. Interestingly, nifedipine has been found to worsen the cramps. Although verapamil, diltiazem, and nifedipine block the L-type calcium channel, nifedipine appears to elicit stronger reflex adrenergic stimulation, activating T-type calcium channels and neutralizing the calcium channel blockade. Magnesium has been used for years to treat cramps in pregnancy and appears to be effective in nonpregnant patients as well. Vitamins B and E have been reported to be effective in reducing the frequency and severity of leg cramps. The author has seen anecdotal improvement of the cramps with gabapentin. All these treatments are much better tolerated than quinine and have less serious potential side effects. Therefore, they are recommended first. There is an increasing number of reports of side effects including pancytopenia, cinchonism, and visual toxicity with the use of quinine. A combination of quinine and aminophylline has showed significant benefit for difficult-to-control patients (

9,

10,

11 and

12).

Sleep Talking

Sleep talking (somniloquy) is characterized by verbal output during sleep. One of the most famous literary examples of sleep talking is the episode of Lady Macbeth by Shakespeare (

1). The talking is sometimes brief or incoherent but occasionally could be long and associated with anger. Sometimes the sleep talking occurs spontaneously, or it could be elicited by talking with the sleeper. It is frequently associated with other parasomnias, such as sleep-walking and confusional arousals. In fact, both in children and in adults, sleep talking is the parasomnia that has been

found to co-occur most frequently with other parasomnias. Emotional stress, concomitant illness, sleep apnea, or sleep terrors can precipitate this phenomenon. Sleep talk is usually harmless and does not require treatment. However, bed partners or family members can be disturbed.

Sleep Starts

Sleep starts or hypnic jerks are common phenomena that occur when the person is just falling asleep; these are characterized by sudden, brief contractions of muscles in the extremities or head lasting from 75 to 250 milliseconds. Also called hypnagogic jerks, they are considered normal physiologic events, although they are poorly understood. Sleep starts mainly involve lower extremities but may also involve the arms and head, with asymmetric single jerks, or asynchronous or massive body movements. Movements may be associated with vivid dreams or hallucinations.

Motor starts are the most common, but visual or auditory sleep start may also occur (a sensation of blinding light coming from inside the eyes or a loud snapping noise that seems to come from inside the head). These sensory phenomena may occur without motor jerk or may precede the body jerk. Although the sensation from sleep starts can be frightening, these occurrences are harmless. Sleep starts can be exacerbated by sensory stimuli, excessive exercise, stress, sleep deprivation, and use of stimulants.

The presumed mechanism involved with this activity is a sudden activation of the mesencephalic reticular-activating system, which is supported by the presence of a brief arousal or wakefulness after the movement. A dissociation between REM and motor inhibition is also postulated. Sometimes it is triggered when the individual is sleeping in a different position than usual, for example, a back sleeper who has fallen asleep on his stomach. They vary in intensity, but when they are strong or very frequent, they disrupt wake-sleep transition and lead to insomnia. Flurazepam has been reported to improve sleep starts (

13).

Arousal Disorders

The arousal disorders are very frequent parasomnias. It has been reported that up to 50% of children have experienced one of these events during childhood (

14). There are three types of arousal disorders according to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders: (a) confusional arousals, (b) sleep terrors, and (c) sleepwalking. They are characterized by behavioral events that occur during SWS. They occur mainly during childhood and some of them, particularly sleep terror and sleepwalking episodes, are disturbing to parents. They tend to improve with age and typically disappear after puberty or in young adulthood.

Sleepwalking may lead to accidents and self-injury. It has been hypothesized that these disorders occur because of incomplete arousal due to disturbed physiologic mechanisms of arousal. SWS fragmentation is the most common finding on polysomnographic studies; PSG has also shown that these parasomnias occur more frequently in the first sleep cycle during SWS. There is a hypersynchronous high-voltage slow-wave (1 ± 3 Hz) activity lasting up to 30 seconds, preceding the behavior activation (

14a). Frequent SWS interruptions by stage 0 have been found in these patients, demonstrating a chronic inability to sustain deep sleep (

15,

16).

The patients may experience a variety of behaviors associated with mental confusion and disorientation. Most of these patients have no memory of the events, but they may remember fragments or vague impressions of the behavior. They are relatively nonreactive to external stimuli and usually are not stereotypic, thus facilitating differential diagnosis from epileptic seizures.

Confusional Arousal

Confusional arousals occur following an attempt to awaken the patient from deep sleep, typically during the first part of the night. Sometimes this disorder is called excessive sleep inertia or sleep drunkenness. These patients react slowly to commands, may have difficulty understanding what they are asked, and often they have problems with short-term memory. Patients with this disorder have very exaggerated slowness, which typically occurs when the individual is awakened from a deep sleep.

These events are very predictable, occurring frequently about 1 hour after going to bed, and are present most commonly when a child is overtired. Other conditions that may trigger these events include stuffy nose, sleep apnea, fever, sore throat, or ear infection. Complete awakenings commonly occur (child goes to the parents’ room at 2:00 AM every night) and may trigger incomplete arousals early in the night that may lead either to confusional arousal or sleepwalking. Behavioral management preventing the late awakening may prevent development of early night arousal disorders. If the child has multiple events in one night, he may have events close to the morning; however, those events tend to be milder than early night ones. The behavior may resemble a temper tantrum.

Confusional arousals start slowly with gradual worsening of the behavior progressing to crying, sitting, and thrashing, which lasts from 5 to 15 minutes and, only rarely, may last up to 45 minutes. Attempting to awaken the child is typically unsuccessful. Confusional arousals are commonly seen in patients with other types of arousal disorders. Night terrors can be differentiated from confusional arousals by their abrupt onset instead of the typical gradual occurrence seen in the latter. In school-aged children, confusional arousal behavior may be related to high-stress situations in a rather quiet and well-behaved child, probably as repressed feelings. Worsening of daytime behavior and control of emotions have been observed to reduce the occurrence of arousal events (

17).

Treatment is very seldom needed. In severe cases, clonazepam given for a short term is very effective, and rarely is long-term therapy necessary.

Night Terrors and Sleepwalking

Sleep terrors are characterized by sudden, terrified screaming associated with an intense autonomic component (tachycardia, tachypnea, diaphoresis, and mydriasis) occurring mainly during childhood. There is disorientation and confusion upon awakening, usually without memory of the event. Often the affected individual sits upright with eyes open, not responding to other people. They may mumble or scream and parents typically describe terrified facial expressions and inability to be consoled. Children typically do not have memory of the event, but adults may partially remember the behavior and have a dreamlike feeling that usually involves a threat by imminent danger, running away from snakes, spider, monsters, and so forth.

Sleep terrors may be more common in males, and occur in about 3% of children and 1% of adults. The investigation of twin cohorts and families with sleep terror and sleepwalking has suggested a genetic factor (

14). PSG is an excellent diagnostic test for this disorder. An abnormally low delta wave EEG and frequent, brief, EEG-defined arousals not associated with clinical wakefulness have been reported.

The sleepwalking events are characterized by sudden automatic behaviors including wandering around the house, sitting in bed, moving objects around, eating, urinating in closets, or going outdoors. A complex activity, such as driving an automobile, is possible, but rare. Patients can be easily stopped by adding a new lock or leaving the keys in a different location. Sleepwalkers are not conscious and, therefore, do not communicate well with others during the event; they usually mumble.

Although sleepwalkers rarely fall down familiar stairs, they need to be kept clear of obstacles; walking at dangerous heights or near sharp objects may result in serious injury. Awakening sleepwalkers should be avoided, since it may cause them to be very confused; in fact, confusional arousals are very frequent in these patients. Sleepwalkers typically go back to bed by themselves. Episodes of sleepwalking usually occur 15 minutes to 2 hours after sleep onset. The prevalence of sleepwalking has been estimated to be about 15% in children and 4% to 10% in adults (

14). There is no sex preference for sleepwalking and is not associated with injuries, but injurious sleepwalking is more predominant in males.

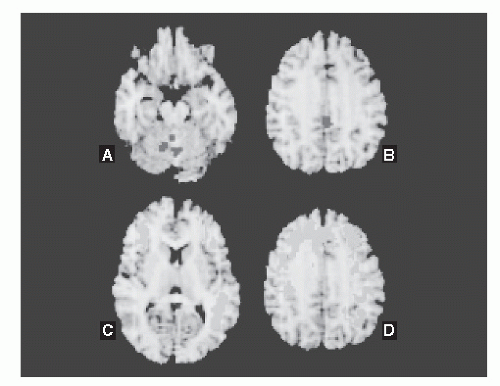

Functional studies with single proton emission tomography during sleepwalking have shown activation of the cerebellum and the posterior cingulate cortex and deactivation of the parietal and frontal association cortex, including the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, mesial frontal cortex, and left angular gyrus, typically seen in normal awake walking individuals (

Fig. 16-2) (

18).

Although sleepwalking and sleep terrors are two different clinical events, they may sometimes be hard to differentiate in adults because screaming can be confused with angry shouting and seeking safety with walking during the episode. Children affected by sleepwalking and sleep terrors usually have complete amnesia about such events. There are several risk factors associated with this disorder, including those associated with drugs, such as lithium carbonate, olanzapine, bupropion, zolpidem, and anticholinergics. Stress and trauma have been implicated as well (

19,

20,

21,

22 and

23).

Other sleep disorders such as SDB and RSL have been associated with an increased incidence of these parasomnias. Furthermore, the improvement of the underlying sleep disorder was found to correlate with the improvement of the parasomnias as well. Psychiatric disorders, including psychologic trauma, are not a common cause. Nightmares are sometimes confused with sleep terrors, but in the later there is usually complete memory of the dream (

Table 16-4).

Occasionally, frontal lobe epilepsy may present clinically as nocturnal terrors, differentiated by stereotyped events,

daytime events, response to antiepileptic drugs, and abnormal EEG. PSG or video EEG monitoring is an excellent tool to differentiate these disorders. Proper and prompt diagnosis is essential for better management and assessment of prognosis (

17,

24). The indications for obtaining polysomnographic studies are summarized in

Table 16-5.

Treatment

Sleepwalking and sleep terrors, especially in children, usually do not require pharmacologic treatment. However, identifying and controlling factors for potential risk of injury is warranted. Scheduled awakenings have been used as an intervention for parasomnias and appear to be effective, according to some reports, but there is insufficient data to support effectiveness; parents are instructed to wake the child 15 to 30 minutes prior to an expected partial arousal event.

Adult patients and children with high-risk sleep-related injury may require pharmacotherapy. Chronic treatment with benzodiazepines has been found to be very effective in adults with sleepwalking, sleep terrors, and other parasomnias. Benzodiazepines are usually well tolerated, with a low incidence of side effects and risk of abuse. Clonazepam, 0.25 to 1.5 mg taken 1 hour before sleep onset, is usually effective. Other drugs used include alprazolam, diazepam, imipramine hydrochloride, and paroxetine hydrochloride. Use of self-hypnosis techniques can be effective in milder cases in both adults and children (

25).