1 Parasomnias can be misdiagnosed and inappropriately treated as a psychiatric disorder.

2 Parasomnias can be a direct manifestation of a psychiatric disorder, e.g. dissociative disorder, nocturnal bulimia nervosa.

3 The emergence and/or recurrence of a parasomnia can be triggered by stress.

4 Psychotropic medications can induce the initial emergence of a parasomnia, or aggravate a preexisting parasomnia.

5 Parasomnias can cause psychological distress or can induce or reactivate a psychiatric disorder in the patient or bed partner on account of repeated loss of self-control during sleep and sleep-related injuries.

6 Familiarity with the parasomnias will allow psychiatrists to be more fully aware of the various medical and neurological disorders, and their therapies, that can be associated with disturbed (sleep-related) behaviour and disturbed dreaming.

7 Parasomnias present a special opportunity for interlinking animal basic science research (including parasomnia animal models) with human (sleep) behavioural disorders.

8 Parasomnias carry forensic implications, as exemplified by the newly-recognized entity of ‘Parasomnia Pseudo-suicide.’ Also, psychiatrists are often asked to render an expert opinion in medicolegal cases pertaining to sleep-related violence.

1 Clinical sleep-wake interview, with review of medical records, and review of a patient questionnaire that covers sleep-wake, medical, psychiatric and alcohol/chemical use and abuse history, review of systems, family history, and past or current physical, sexual, and emotional abuse.

2 Psychiatric and neurologic interviews and examinations, including psychometric testing.

Table 4.14.4.1 Classification of parasomnias: primary and secondary sleep phenomena

Primary sleep phenomena

Non-REM sleep

Disorders of arousal: sleepwalking/sleep terrors/confusional arousal

REM sleep

REM sleep behaviour disorder (RBD)

Dream anxiety attacks (nightmares)

Miscellaneous (including mixed non-REM/REM sleep)

Parasomnia overlap disorder (sleepwalking/sleep terrors/RBD)

Sleep related eating disorder

Restless legs syndrome/periodic limb movements in sleep

Obstructive sleep apnoea-related parasomnias

Rhythmic movement disorders

Status dissociatus

Bruxism

Secondary sleep phenomena

Central nervous system

Seizures (conventional, unconventional)

Headaches

Psychiatric

Nocturnal dissociative disorders

Nocturnal panic attacks

Nocturnal bulimia nervosa

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Cardiopulmonary (arrhythmias, asthma, etc.)

Gastrointestinal (gastro-oesophageal reflux etc)

Malingering

Modified from Mahowald and Ettinger.(7)

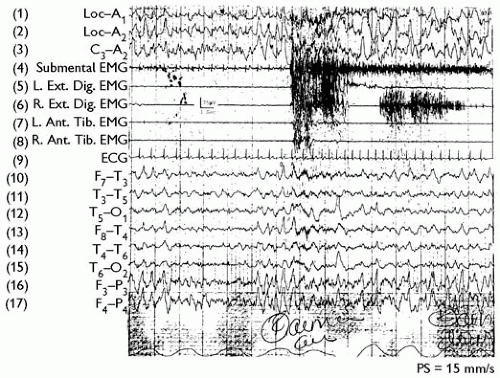

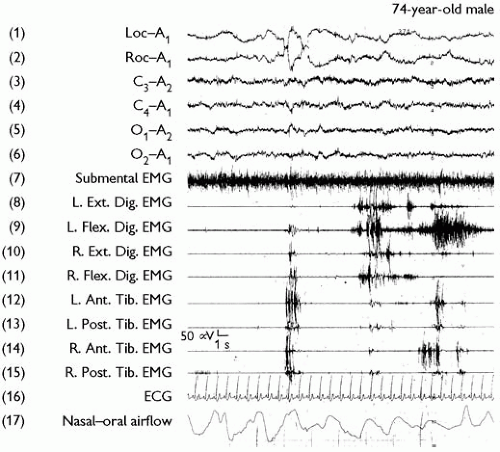

3 Extensive overnight polysomnographic monitoring at a hospital sleep laboratory, with continuous audio-visual recording. Figures 4.14.4.1, 4.14.4.2 depict the polysomnographic montage that includes the electro-oculogram, EEG, chin and four-limb electromyograms, ECG, and nasal-oral airflow (with full respiratory monitoring whenever indicated). Polysomnographic recording speeds of 15 to 30 mm/s are employed in order to detect epileptiform activity. Urine toxicology screening is performed whenever indicated.

4 Daytime multiple sleep latency testing, if there is a complaint or suspicion of excessive daytime sleepiness or fatigue (methods discussed in Narcolepsy chapter).

1 Sleepwalking/sleep terrors (M:F 3:2; mean age of onset, 5 years);

2 REM sleep behaviour disorder (predominantly male; mean age of onset, 57 years)

3 Dissociative disorders (Mostly female mean age of onset, 21 years)

4 Nocturnal seizures (uncommon)

5 Obstructive sleep apnoea/periodic limb movements (uncommon).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree