Parasomnias

Sonya Abercrombie

Joseph W. Anderson

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this chapter, the reader should be able to:

1. Express a basic understanding of nonrapid eye movement and rapid eye movement parasomnias.

2. Recognize clinical presentation to enhance documentation procedures.

3. Recognize issues that require a technologist response.

4. Identify a parasomnia that occurs during the polysomnographic recording.

5. Describe the processes related to responding to the patient exhibiting a parasomnia event during the sleep study.

6. Differentiate between parasomnias that usually occur in children or in adults or in both.

KEY TERMS

Parasomnia

Arousal

REM sleep

NREM sleep

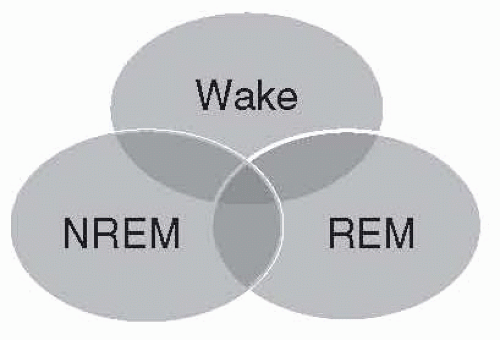

Parasomnias are undesirable physical phenomena that occur predominantly or exclusively during the sleep period (1, 2). Classification by the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd edition (ICSD-3) is as follows (Fig. 18-1):

During nonrapid eye movement (NREM) sleep.

Associated with rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.

During the transition from wakefulness to sleep and from sleep to wakefulness.

The pathogenesis of the various parasomnias remains incompletely understood. It is believed that the simultaneous occurrence or rapid oscillation of the various state-determining variables of wakefulness, NREM or N3 sleep, and REM sleep may give rise to the intrusion of elements of one state into another. Therefore, a combination of wakefulness and NREM sleep produces disorders of arousal (DOA), and persistence of REM sleep and elements of wakefulness result in REM behavior disorder (RBD) (3). Parasomnias are, thus, especially likely to emerge during the transition periods from one state to another and may consist of complex seemingly purposeful behaviors. These behaviors may not be recalled by the patient upon awakening. These actions are often termed automatisms, apparently without any conscious motivation or control. Patients may have more than one parasomnia, and overlapping features of parasomnias can make it difficult to differentiate between the parasomnias and seizure (4).

DISORDERS OF AROUSAL (FROM NREM SLEEP)

DOA occur primarily out of NREM sleep, particularly stage N3 sleep, and are more prevalent during the first third of the night. There is often a strong familial pattern. These disorders are most commonly encountered during childhood, and their frequency often diminishes with increasing age as stage N3 sleep declines. These disorders are believed to result from abnormal arousal processes, when motor activity is restored without full consciousness.

Confusional Arousals

Confusional arousals, also termed “sleep drunkenness,” are seen more commonly during the first third of the night, when NREM stage N3 sleep is most prevalent. Confusional arousals are characterized by diminished vigilance, excessive sleep inertia, unclear thoughts, and slowed speech. Behaviors tend to demonstrate lack of

orientation to the environment. The person may react inappropriately, be resistive, and even violent. Episodes may last minutes or hours. Consoling the person can cause even more agitation. These arousals may be associated with behaviors that are inappropriate, violent, resistive, or otherwise bizarre. These episodes may also occur during morning awakening (1).

orientation to the environment. The person may react inappropriately, be resistive, and even violent. Episodes may last minutes or hours. Consoling the person can cause even more agitation. These arousals may be associated with behaviors that are inappropriate, violent, resistive, or otherwise bizarre. These episodes may also occur during morning awakening (1).

Confusional arousals may be caused by sleep deprivation, the use of central nervous system (CNS) depressants, neurologic disorders, or forced awakenings from deep sleep. They are most prevalent in young children and are less common among adults. There is no gender difference (4). During an episode of confusional arousal, polysomnographic (PSG) recordings may demonstrate an alpha rhythm, repetitive microsleeps, or stage N1 sleep activity.

Treatments may include sleep extension, scheduled awakenings, avoidance of sleep deprivation, psychotherapy, or drug therapy (e.g., tricyclic antidepressants or benzodiazepines) (5). Treatment for children may not be required because time may be all that is required for the arousals to disappear (4).

Sexsomnia

Sexsomnia is an NREM parasomnia in which the patient has atypical sexual manifestations during sleep, such as masturbation, fondling, and sexual intercourse followed by morning amnesia (1, 6). PSG data demonstrate sudden spontaneous arousals from non-REM slow-wave (N3) sleep (6). The ICSD-3 considers sexsomnia a “confusional arousal.” Terms used in the literature are “atypical sexual behavior during sleep,” “sexsomnia,” or “sleep sex.” Sexsomnia is a recently reported variation of NREM arousal parasomnias (1, 4). These behaviors often occur during confusional arousals and have been reported during somnambulism (somnambulistic sexual behavior) (1). Most people reporting sexsomnia have had past episodes of sleepwalking (6). Sleepwalking does not present with sexual arousal; however, sexsomnia is associated with engorgement of the sexual organs, lubrication, and ejaculation. Confusional arousals are different, in that movement is related to the person’s agitation and confusion with crying and screaming and there is no sexuality to it. Males are described as being more physical, with sexual fondling and intercourse often occurring, whereas females are more likely to present with masturbation and vocalization of a sexual nature (6).

This parasomnia can be quite disturbing, making relationships difficult as both partners suffer utterly different emotions about themselves and yet must muster empathy for the other. This can strain marriages and cause relationships much hardship. The medicolegal ramifications can also be substantial.

There is some evidence that alcohol and drug abuse may be factors in some cases in addition to stress and sleep deprivation. Past trauma may also be a factor. PSG performed to capture these episodes may need to be repeated in order to capture an episode. Home sleep testing may be of benefit in these patients. Home studies also allow the patient to mimic behaviors seen at home that are not allowed in the lab: same sleeping partner, alcohol use, and so on.

Parasomnias Because of Medications or Substances

Association between medications or other substances and the induced parasomnias is increasingly recognized. Parasomnias may be associated with the use or withdrawal of a substance, often a medication, and the associated nonconscious behaviors can occur during NREM or REM sleep. The ICSD-3 does not list substances that cause this specific disorder. The literature does cite cases and this is a cursory overview of some of these cases.

The newer “Z drugs” are being seen in the literature with often bizarre consequences. Zolpidem (Ambien), zaleplon (Sonata), and eszopiclone (Lunesta) are benzodiazepine receptor agonists that react with α1 γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)A receptors, thought to eliminate sedative, amnesic, and motor impairment actions associated with benzodiazepines that react at other GABA receptor sites (7). Zolpidem states, on its packaging materials, that alcohol or other CNS depressants when taken together may increase the risk of associated parasomnias. The behaviors or automatisms involved, such as sleep driving and sleep shopping, are parasomnias associated with DOA, RBD, or parasomnia overlap disorder (4, 7). Sexsomnia, somnambulism, and sleep-eating can also be seen as a result of medication or substance use. These topics are covered under their own headings.

Somnambulism was reported in a case study where bupropion’s use may have initiated somnambulism episodes; when the medication was discontinued, the sleepwalking was curtailed (8). The bupropion (a noradrenaline and dopamine reuptake inhibitor) was prescribed for use during smoking cessation; however, because of nicotine withdrawal, bupropion could not be assumed causal in this case (8). Another case report describes a patient prescribed bupropion for depression, who about 2 weeks later was discovered to be leaving her bed, making phone calls, and bringing back food that she hid under her pillow. Bupropion was stopped, and

that night so did the parasomnia. Months later, another physician prescribed bupropion and the parasomnia returned in about 2 weeks. Again, the parasomnia went away the first night she stopped taking the bupropion. Bupropion increases slow-wave sleep and also REM total duration, density, and latency (8).

that night so did the parasomnia. Months later, another physician prescribed bupropion and the parasomnia returned in about 2 weeks. Again, the parasomnia went away the first night she stopped taking the bupropion. Bupropion increases slow-wave sleep and also REM total duration, density, and latency (8).

Patient medications and other substances used by patients tend to present problems in the study of parasomnias and also in their treatment. New classes of sleep medications and substances that have been around for years (e.g., alcohol) can be the cause of parasomnias. The use of these substances is increasing, and more reporting has indicated a likely relationship between their use and some parasomnias.

Although we would normally expect to see a short amount of time between starting a new medication and seeing a reaction to it, many medications take weeks for their full effects to be established. Polypharmacy presents confounding evidence of what medication may be causing a parasomnia. The drug or drugs used to treat an original disorder may cause the problem, but it may also be an interaction between several medications that is the cause. Patients can be taking large numbers of drugs for comorbid and morbid conditions unrelated to sleep. It has been postulated that parasomnias, such as sexsomnia, may emerge because of medication initiation or withdrawal (4).

These parasomnias may be quite dangerous and yet unknown to the patient for a time before he or she or his or her physician is able to put the pieces together and identify that he or she has a sleep disorder. RBD, discussed later in this chapter, can be associated with the use of medications and biologic substances and is an example of a disorder that can be dangerous to the patient or others in the proximity of the patient having an episode.

Treatment of these parasomnias may consist of removal of the offending medication or substance. Changes in dosage and timing of medication may also prove beneficial.

Sleepwalking

Sleepwalking or somnambulism refers to ambulation that occurs during sleep. Somnambulism is considered a DOA and is most commonly seen in the first third of the night, when NREM stage N3 sleep is more prominent. The episode will often start with the person sitting up in bed, followed by walking or running. The sleepwalker may return to bed without waking or wake somewhere else. Behaviors may occasionally be inappropriate, such as driving a car over long distances. It is associated with diminished arousability and inappropriate behaviors, sometimes highly elaborate, and amnesia for the event. The sleepwalker’s eyes are usually wide open, but attempts to communicate are usually unsuccessful. Episode duration varies widely from several minutes to an hour. It is most prevalent in young children and is less common in adults (9, 10). Familial occurrence is common (11, 12).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree