Parieto-Occipital Lobe Epilepsy

Parieto-Occipital Lobe Epilepsy

Introduction

Epilepsy arising from the posterior cortex poses many challenges to the clinician. Occipital lobe and parietal lobe epilepsies are defined as epilepsy whose ictal discharges arise from the occipital and parietal lobes respectively. These epilepsy syndromes are rare; one study showed a prevalence of 8% for occipital lobe epilepsy and no more than 5% in another study for parietal lobe epilepsy.

A particular challenge in these epilepsies is that many forms of parietal and, occasionally, occipital lobe epilepsy are that the seizure may have very few semiological features that indicate onset in these regions. The clinical semiology of these epilepsies may only manifest following spread to adjacent regions of the cortex. The next challenge arises from usually poorly localizable electroencephalography (

EEG) patterns, both interictally and ictally. Again, the

EEG findings can arise from the ictal spread, rather than from the ictal onset. A carefully taken history is essential for the correct diagnosis of these epilepsies, as they can easily be misdiagnosed for temporal lobe or frontal lobe epilepsy as well as migraine headaches.

Particular attention should be paid to the symptoms, especially sensory symptoms and auras that occur at the very beginning of seizures, as they usually reveal the useful clinical clues to the localization of the actual ictal onset zone. Unlike most epilepsies the neurological examination can yield important findings that result from the epileptogenic zone. Patients often present with a variety of visual field deficits contralateral to the epileptogenic zone and sometimes are unaware of these deficits. Advances in neuroimaging have also greatly helped to identify possible surgical candidates, which before were either simply diagnosed with cryptogenic epilepsy or misdiagnosed with temporal or frontal lobe epilepsy.

Anatomy of posterior cortex

Parietal lobe

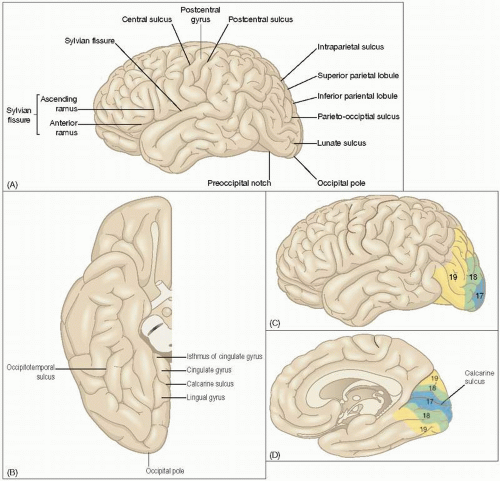

The parietal lobes account for 25% of the brain’s volume and only represents 5% of focal epilepsies. The anterior border of the parietal lobe is created by the central sulcus; however, the occipital and temporal borders are more complicated to define. A hypothetical vertical line that cuts the convex surface of both lobes by joining the parieto-occipital sulcus to a shallow depression on the inferior lateral hemispheric border approximately 4 cm from the occipital pole defines the occipital border. An arbitrary line extending posteriorly from the Sylvian fissure to the occipital-parietal line defines the temporal border. See

7.1.

Occipital lobe

The occipital lobe is the most posterior part of the brain and only occupies approximately 10% of its volume. The arbitrary line that separates the parietal and temporal lobes is continued transversely across the inferior surface of the brain to the parieto-occipital fissure. This lobe is further divided on the medial surface by the calcarine sulcus into the superior lying cuneus and the inferior lying lingual gyrus (

7.1A,B).

Functional anatomy of the posterior cortex

Parietal lobe

It should be noted that the anatomical definition of the parietal lobe is arbitrary and does not reflect the functionality of the involved cortex. The parieto-occipito-temporal association cortex deals with higher perceptual function

and is responsible for the integration of primary sensory inputs to these lobes. The postcentral gyrus runs parallel to the precentral gyrus and represents the somatosensory area. Brodmann divided this gyrus into areas 1, 2, 3a and 3b, which are all important in different aspects of somatic sensation. Topographical representation of contralateral body parts is found here, supramedially for the foot and leg and for the arm, hand and face as one moves in the lateral direction. A second somatosensory area with mainly contralateral (although bilateral representation is minimally present) somatotropic representation is found on the superior border of the Sylvian fissure. This area also serves taste and is located adjacent to the sensory cortex for the tongue and pharynx. The third somatosensory area is located in the posterior parietal lobe; it relates sensory and motor information and integrates the different somatic sensory modalities for perception (

7.1). Lesions in the left angular gyrus can lead to Gerstmann’s syndrome, which is a tetrad of finger agnosia, right-left confusion, agraphia and acalculia.

Occipital lobe

The cortex of this lobe represents most modalities of vision; it is responsible for the perception of colours and movement as well as other complex aspects of vision, including the association of present and past visual experiences. The primary visual cortex borders inferiorly the calcarine sulcus, topographically representing the visual fields. Brodmann’s area 17 corresponds to the primary visual cortex and the visual association cortices are formed by Brodmann’s areas 18 and 19 (

7.1C).

Seizure semiology

The characteristic phenomena of seizures arising from the parietal and occipital lobes can be subjective sensations, as these lobes primarily subserve sensory perception. Seizure semiology may be divided into positive and negative sensory phenomena, with patients reporting sensations when none are occurring or the feeling of the inability to move or absence of a limb.

Tables 7.1 and

7.2 list features of seizures with the lobe of their respective ictal onset zone.

Parietal lobe epilepsy

Somatosensory seizures often involve the contralateral face or limbs with a broad spectrum of sensations being reported, e.g. numbness, tingling, thermal sensations of burning, genital sensations, or cold, vertigo, panic, disturbances in body image and gustatory phenomena. Psychic auras, epigastric sensations and ictal amaurosis suggest that ictal spread to extraparietal regions has already occurred. Single photon emission computed tomography (

SPECT) studies have shown a hyperperfusion

of the anterior parietal lobe with sensorimotor semiology and with staring and altered awareness show a hyperperfusion of the posterior parietal lobe. Ictal spread to the frontal lobes usually results in asymmetric posturing of the extremities, unilateral clonic activity, contralateral version (tonic turning of either eye with or without head resulting in unnatural posturing), and hyperkinetic activity such as myoclonus. Spread to the temporal lobes leads to altered consciousness and automatisms, which are similar to those seen in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy.

Occipital lobe epilepsy

Visual phenomena play a central role in the semiology of occipital lobe epilepsy, especially at the beginning of the seizure. Sensations of ocular movement without any detectable movement, nystagmus, eye flutter and forced eye blinking are typical of such seizures. Visual symptoms may be positive such as coloured or bright elementary hallucinations or they may be negative such as scotomas, contralateral hemianopias and amaurosis. In approximately 75% of children with occipital lobe epilepsy, altered consciousness and motor signs were seen, and contralateral version was seen most frequently. Important seizure propagation patterns include the infra-Sylvian and the supra-Sylvian paths. The infra-Sylvian pattern, which spreads to the temporal lobe, is the most common and associated with automatisms, typical of temporal lobe epilepsy and loss of awareness. The supra-Sylvian pattern spreads to the mesial frontal regions and results in contralateral asymmetric tonic posturing or myoclonus. Other patterns of ictal propagation include lateral propagation, which results in focal motor or sensory seizures.

Electroencephalography in parietooccipital epilepsy

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access