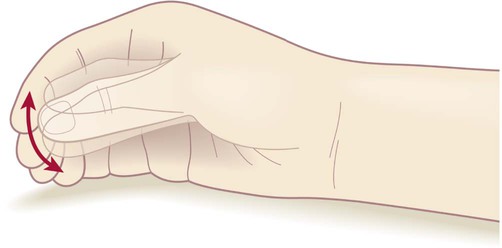

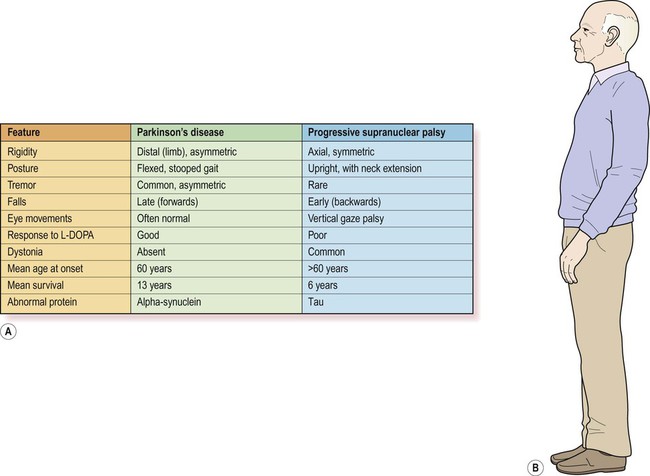

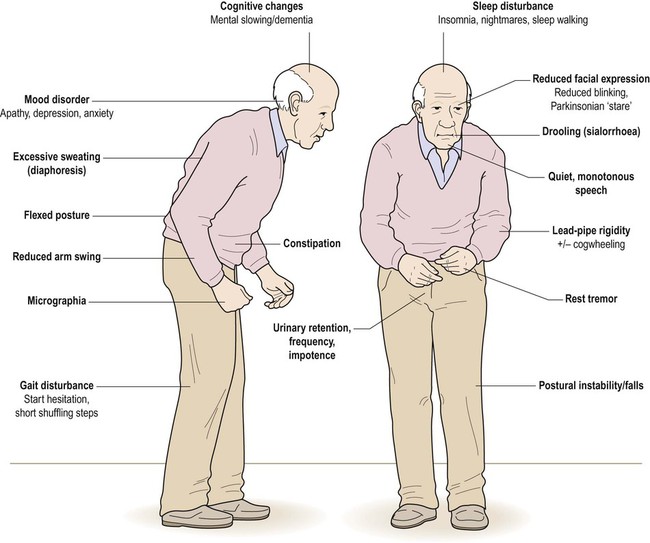

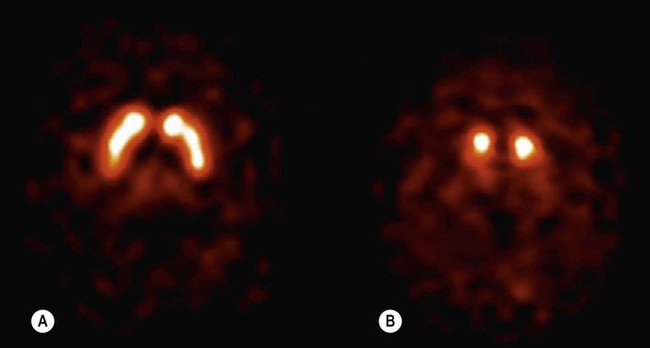

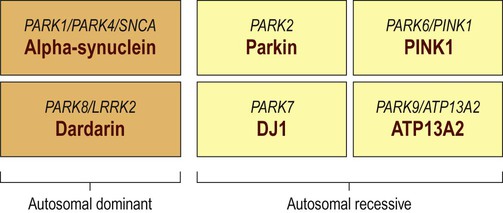

Most cases of Parkinson’s disease are idiopathic (meaning that the cause is not known). The main symptoms and signs of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (IPD) are illustrated in Figure 13.1. The central feature is akinesia or poverty of movement (Greek: a-, without; kinesis, movement) together with marked muscular rigidity. It is therefore classified as an akinetic-rigid syndrome. Another prominent component is bradykinesia, meaning that movements are slow and deliberate (Greek: bradys, slow). In most cases there is also a coarse tremor. Parkinson’s disease is sometimes referred to as an extrapyramidal movement disorder since the pyramidal (primary motor) pathway is unaffected. Increased muscle tone (rigidity) may present as stiffness, muscle pain or fatigue. On examination, there is uniform resistance to joint flexion and extension which has been compared to bending a piece of lead pipe. In contrast to spasticity, lead-pipe rigidity is constant (not velocity-dependent) and may be due to over-activity in the long-latency component of the stretch reflex (see Ch. 4). Tremor is a rhythmic ‘back-and-forth’ movement in the limbs, head or jaw and occurs in 75% of patients with Parkinson’s disease. The parkinsonian tremor is usually asymmetric and often begins in one hand or arm. It is classified as a rest tremor because it is much more prominent between movements. It is of large amplitude and low frequency (4–6 Hz) and is not present during sleep. Some patients have a classical ‘pill-rolling’ tremor (Fig. 13.2) which is strongly suggestive of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. The combination of lead-pipe rigidity and tremor creates a jerky or ‘ratchet-like’ sensation on examination. This is termed cogwheeling and is best appreciated at the wrist. Non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease reflect: (i) the role of the basal ganglia in cognition, emotion and behaviour (see Ch. 3); and (ii) the presence of widespread pathological changes in the brain stem, limbic lobe and neocortex. Anxiety, depression or apathy occurs in 40% of patients. There may be sleep disorders including: nocturnal hallucinations, excessive daytime somnolence, vivid dreams, nightmares or sleepwalking. Subtle cognitive changes are common, such as bradyphrenia (generalized slowing of thought) or executive dysfunction (difficulty with organization, planning and decision-making). One in five patients will eventually be diagnosed with dementia (Clinical Box 13.1). The diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease is primarily clinical. Routine MRI scans are often normal, but dopamine deficiency in the basal ganglia can be demonstrated using specialized tests (Fig. 13.3). Without treatment there is progressive decline over a 5–10-year period, with gradual deterioration of motor function, worsening postural instability, gait freezing and frequent falls. However, symptoms can usually be controlled for a number of years with dopamine replacement therapy and this is associated with a near-normal life expectancy. Patients with cerebrovascular disease may develop an akinetic-rigid syndrome. This is due to microinfarcts (small ischaemic strokes, see Ch. 10) in the basal ganglia or hemispheric white matter. In contrast to idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, symptoms tend to be more severe in the lower limbs, response to dopamine replacement is poor and tremor is usually absent. A number of other neurodegenerative disorders may be confused with Parkinson’s disease. The most important are progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and multiple system atrophy (MSA), each with a prevalence of approximately 1 in 20,000. An even rarer form is corticobasal degeneration (CBD), discussed in Clinical Box 13.2. This is the most common neurodegenerative mimic of Parkinson’s disease, accounting for about 5% of people with a parkinsonian syndrome. In more than 50% of cases there is axial rigidity, a hyperextended posture and a characteristic supranuclear gaze palsy with failure in the cortical (‘supranuclear’) control of vertical eye movements. There may also be apathy, cognitive decline and outbursts of inappropriate laughter or tearfulness, termed emotional incontinence. This classical form of PSP is also referred to as Richardson’s syndrome. In up to a third of cases the clinical features closely resemble idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. In this subtype, referred to as PSP-P, the pathological changes are less severe and the clinical course is more favourable. Features of PSP and Parkinson’s disease are compared in Figure 13.4. Multiple system atrophy is characterized by parkinsonism, cerebellar ataxia and autonomic dysfunction. There are two patterns. MSA-P is dominated by rigidity, bradykinesia and postural instability and closely resembles idiopathic Parkinson’s disease; whereas MSA-C combines features of cerebellar ataxia with corticospinal tract signs including increased muscle tone and reflexes (see Ch. 4). The key pathological change in Parkinson’s disease is loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra of the midbrain (Fig. 13.5). This is associated with degeneration of the nigrostriatal tract, leading to a profound reduction of dopamine in the basal ganglia (typically below 20% of normal at presentation). Surviving nigral neurons contain cytoplasmic inclusions called Lewy bodies, which can be identified by antibody labelling for the major component, alpha-synuclein protein. This reveals widespread pathological changes throughout the brain stem, limbic lobe and neocortex. The substantia nigra is a large midbrain nucleus that can be divided into compact and reticular parts. The pars compacta contains the cell bodies of dopaminergic neurons contributing to the nigrostriatal tract, whereas the pars reticulata consists of GABAergic neurons and is analogous to the globus pallidus. The substantia nigra is almost black in the adult brain (Latin: nigra, black) due to the accumulation of neuromelanin as a by-product of dopamine synthesis (see Ch. 7). Loss of dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson’s disease causes pallor of the substantia nigra which can be seen at post-mortem examination. The lateral part of the substantia nigra (which projects to the putamen or ‘motor striatum’) is more severely affected than the medial portion (which projects to the caudate nucleus). Neuronal loss is also seen in other parts of the nervous system in patients with Parkinson’s disease. These include the noradrenergic locus coeruleus of the pons (see Ch. 1). Post-mortem examination of the brain in Parkinson’s disease may therefore show pallor of the loci coerulei as well as the substantia nigra. Despite normal age-related degeneration of the substantia nigra, most people have sufficient reserve capacity so that striatal dopamine levels never fall below 20% of normal. The pathological hallmark of Parkinson’s disease is the Lewy body (Fig. 13.6). This is a type of pathological inclusion (abnormal protein aggregate) found in the cytoplasm of surviving neurons. Lewy bodies are spherical structures, measuring 5–30 µm in diameter. They are pink on standard histological preparations (because they take up the red tissue dye eosin) and are surrounded by a pale halo. Lewy body pathology begins in the medulla and olfactory bulbs, spreading progressively through six Braak stages to involve the pons, midbrain, limbic lobe, amygdala and neocortex (Fig. 13.7). Cortical Lewy bodies are similar to those encountered in the brain stem, but do not have a halo and are present even in cases without dementia. Pathological inclusions are also found in the autonomic nervous system, including the enteric nervous system in the gastrointestinal tract. The main constituent of Lewy bodies is alpha-synuclein. This is a synaptic protein that is present in presynaptic terminals in association with synaptic vesicles. It seems to be involved in neurotransmitter release and synaptic plasticity (which is critical for learning and memory; see Ch. 7). It may also take part in the regulation of dopamine storage and synaptic vesicle recycling. Accumulation of alpha-synuclein (within neurons and glia) occurs in several other parkinsonian syndromes including Parkinson’s disease with dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and MSA (Fig. 13.8) which are all classified as synucleinopathies. In other forms of parkinsonism such as PSP and CBD there is accumulation of the microtubule-associated protein tau and these disorders are therefore classified as tauopathies. The molecular classification of neurodegenerative diseases is discussed in Ch. 8. Five to ten percent of Parkinson’s disease is familial. Around a dozen genes have been identified and the six best understood are shown in Figure 13.9. Some genes have one name connected with the protein encoded and another that is based on the order of discovery (PARK1, PARK2, etc.). The names can be confusing (for instance, it turns out that PARK1 and PARK4 are the same gene). With Parkin gene (PARK2) mutations, disease onset is usually below the age of 40 years and these mutations account for 50% of autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism (ARJP). Parkin is a ubiquitin-ligase which is involved in ubiquitination and targeting of proteins for degradation by the proteasome (discussed below; see also Ch. 8). Most Parkin gene mutations reduce the ability to form protein aggregates and Lewy bodies are therefore absent.

Parkinson’s disease

Clinical features

The combination of a flexed posture, slow shuffling gait, mask-like facial expression and unilateral tremor is highly characteristic.

Muscular rigidity

Rest tremor

Other features

Diagnosis and course

(A) Axial section through the basal ganglia showing the normal pattern of uptake in a healthy control. The characteristic ‘comma’ shape of the striatum (caudate nucleus and putamen) is seen; (B) In a patient with Parkinson’s disease, there is markedly reduced signal in the putamen but not in the head of the caudate nucleus, creating a ‘full stop’ appearance. [Images obtained using single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) with the radioactively labelled (123I) beta-CIT.] From Seibyl, JP: Single-photon emission computed tomography and positron emission tomography evaluations of patients with central motor disorders. J Semin Nuclear Med (2008) with permission.

Parkinsonism

Vascular pseudoparkinsonism

Neurodegenerative causes

Progressive supranuclear palsy

Multiple system atrophy

Pathology of Parkinson’s disease

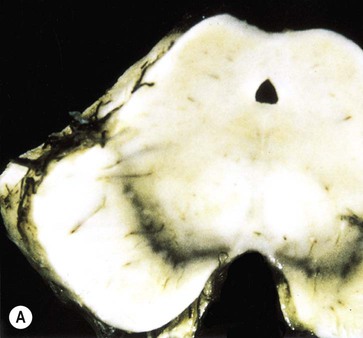

(A) Normal midbrain (in cross section) with a deeply pigmented substantia nigra; (B) Pallor of the substantia nigra in a case of Parkinson’s disease. From Kumar et al: Robbins and Cotran’s Pathologic Basis of Disease 7e (Saunders 2004) with permission.

Neuronal loss

Lewy bodies

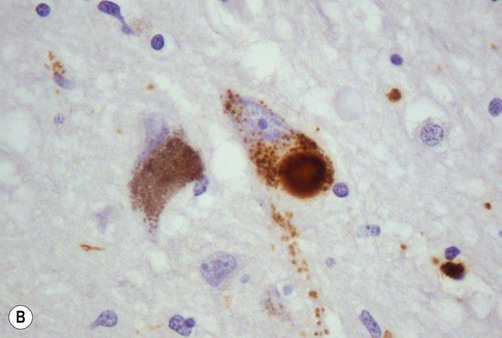

(A) On routine haematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections Lewy bodies appear as bright pink structures in the neuronal cytoplasm, surrounded by a pale halo; (B) They can also be demonstrated by immunohistochemistry for alpha-synuclein protein, which is the main constituent. Courtesy of Professor Steve Gentleman.

Progression of Lewy body pathology

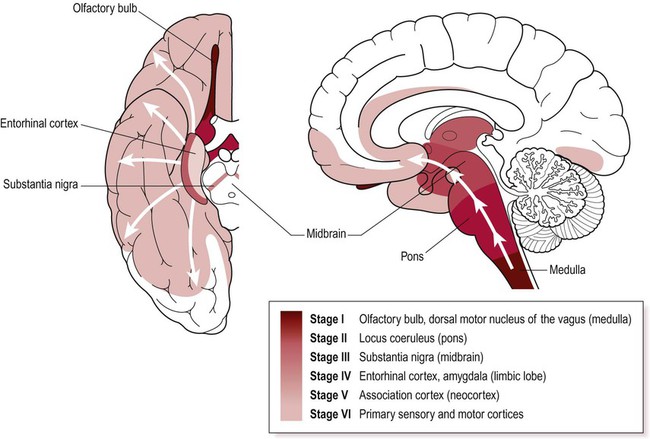

Lewy bodies first appear in the medulla and olfactory bulb and then progressively spread to the pons, midbrain, limbic lobe and neocortex. Key anatomical structures involved in each of the six Braak stages are indicated and disease progression is colour-coded on the inferior and midsagittal views of the cerebral hemisphere. Modified from Braak H et al: Neurobiology of Aging 24 (2003) with permission.

Alpha-synuclein

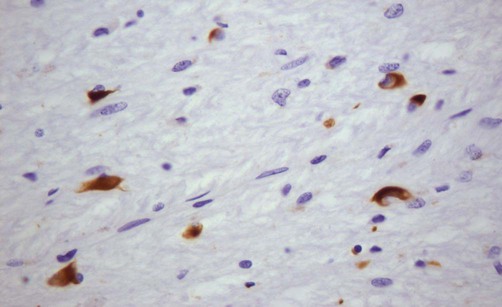

This microscopic image shows glial cytoplasmic inclusions (GCIs) within oligodendrocytes in a case of MSA, highlighted by immunohistochemistry (antibody labelling). Courtesy of Professor Steve Gentleman.

Familial Parkinson’s disease

Around a dozen genes have been identified in association with familial Parkinson’s disease, but the six best understood are illustrated. In each case the different names for the genes are shown above the protein encoded.

Autosomal recessive PD

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Parkinson’s disease