Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis

Lauren B. Krupp

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an immune-mediated inflammatory demyelinating disorder of the central nervous system (CNS). MS can develop in children and adolescents, although usually it affects young and middle-aged adults. An estimated 2% to 3% of patients with MS are younger than 18 years (1,2). They represent an underserved, understudied MS subgroup. Although much of our understanding of the pathogenesis, clinical and radiologic features, and treatment of MS is based on studies of adult patients, the clinical and research experience with children has grown. The study of pediatric MS has the potential to provide insights into the nature of MS for all affected individuals.

MS is now a treatable disease, whereas, prior to 1993, no therapies to alter the disease course were available. The ability to treat MS has accelerated the need to establish an accurate diagnosis quickly, particularly in children, because treatment is most effective when started early in the disease course (3). Fortunately, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has facilitated the diagnosis.

Definition

To facilitate clinical research and establish uniform criteria for the diagnosis, an operational and consensus-based definition for pediatric MS was developed. Although it still must be tested in prospective longitudinal studies (4), the definition is a first step in recognizing the key elements of the pediatric MS diagnosis. The criteria for the diagnosis require:

1. Multiple episodes of CNS demyelination disseminated in time and space with no lower age limit.

2. MRI findings can be applied to meet dissemination-in-space criterion if they show three of the following four features (a) nine or more white matter lesions or one gadolinium-enhancing lesion, (b) three or more periventricular lesions, (c) one juxtacortical lesion, and (d) an infratentorial or spinal cord lesion.

3. The combination of an abnormal cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) and two lesions on the MRI, of which one must be in the brain, can also be used to meet dissemination-in-space criterion; the CSF must show either oligoclonal bands (OCBs) or an elevated immunoglobulin G (IgG) index.

4. MRI can be used to satisfy criteria for dissemination in time after the initial clinical event, even in the absence of a new clinical demyelinating event. A new gadolinium-enhancing lesion or new T2 lesion 3 months after the clinical event can be a surrogate for another clinical event.

The diagnosis of MS relies on the clinical features of the disease. CSF can help exclude other conditions, such as lymphoma or Lyme disease, and can provide additional confirmation by the presence of either OCBs (immunoglobulins whose antigenic target still remains unclear) or an elevated IgG index (the relative amount of IgG in the CSF compared with the serum). In some instances of MS, the CSF may be negative for OCBs and the IgG index. Typically, the cell count in the CSF is less than 50 cells per milliliter. Evoked-potential testing also is useful for identifying silent lesions but is less sensitive than MRI.

Demographic Features

The exact prevalence of pediatric MS is unknown. The studies that suggest a prevalence of 3% to 5% among children younger than 16 years are all retrospective (5). Nonetheless, if approximately 4% of the MS population is younger than 18 years, it can be estimated that worldwide, 100,000 or more children have MS. The frequency of MS steadily increases with age, such that in a fraction of a percentage, MS develops during early childhood, whereas among teens, the frequency is closer to 3%.

The disease usually begins with a mean age at onset between 8 and 14 years, depending on whether the cohort has a cut-off below 16 or 18 years (1,2,6). The distribution of boys and girls varies according to age. For children age 10 years or older, girls outnumber boys by approximately 2.5:1 (1,2,7,8). For children younger than 10 years, the ratio of girls and boys is approximately 0.5:1 (9,10). The increase in girls during puberty is recapitulated in adult MS. Whereas more women than men with MS are among the 20- to 40-year-old age group, in older age groups (consistent with the menopausal age range), men begin to equal women in frequency. These demographic features suggest that sex hormones play a role in MS pathogenesis. Additional evidence pointing to the role of sex hormones comes from a pilot clinical trial of MS in men that showed protective effects of testosterone (11).

Clinical Findings

SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS

Presenting symptoms of MS often depend on the location of the white-matter lesions. Initial symptoms typically include optic neuritis (unilateral or bilateral), motor weakness, balance problems, sensory disturbance, loss of coordination, bladder dysfunction, or problems related to brainstem involvement (facial numbness, diplopia). In different clinical series, motor, visual, or sensory disturbances are the most common presentation (5). A polysymptomatic onset has been described in 8% to 67% of the patients (1,2,5,7).

At presentation, children compared with adults tend to have more brainstem and cerebellar symptoms, encephalopathy, or optic neuritis (12,13). Among those younger than 6 years, seizures, marked alteration in consciousness, a polysymptomatic onset, and atypical MRIs are more frequent (9,12).

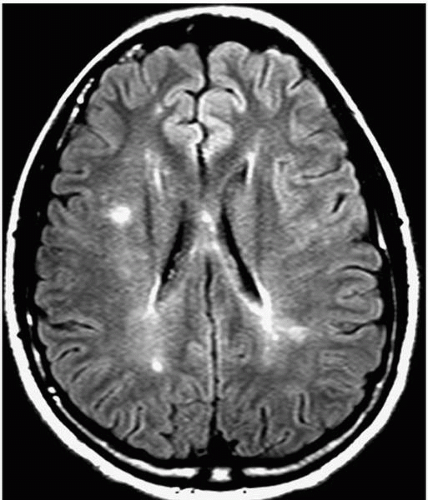

MRI FINDINGS

The MRI is extremely valuable in the diagnosis of MS. In contrast to other demyelinating disorders of childhood, MS lesions predominantly involve the white matter (Fig. 15.1). Cortical or central gray matter involvement is uncommon (6). The lesions tend to be discrete, often associated with gadolinium enhancement, and are usually periventricular (7). Although it is less true of the youngest pediatric MS group, many older children have MRI

findings that are similar to those of adults. In adults, criteria for a “positive MRI” include three of the four requirements: (a) one gadolinium-enhancing lesion or nine lesions involving the white matter, (b) three or more periventricular lesions, (c) an infratentorial, and (d) a juxtacortical lesion. A lesion involving the spinal cord can be used as either one of the nine lesions or instead be of an infratentorial location. If a child or teenager with possible MS meets the MRI criteria established for adults with MS, then the MRI findings are highly supportive of the MS diagnosis. Moreover, these children tend to have a worse prognosis than do those whose MRIs are less specific.

findings that are similar to those of adults. In adults, criteria for a “positive MRI” include three of the four requirements: (a) one gadolinium-enhancing lesion or nine lesions involving the white matter, (b) three or more periventricular lesions, (c) an infratentorial, and (d) a juxtacortical lesion. A lesion involving the spinal cord can be used as either one of the nine lesions or instead be of an infratentorial location. If a child or teenager with possible MS meets the MRI criteria established for adults with MS, then the MRI findings are highly supportive of the MS diagnosis. Moreover, these children tend to have a worse prognosis than do those whose MRIs are less specific.

Some children with MS who lack typical MRI findings can have large tumefactive lesions associated with edema, rarely a mass effect, or deep grey-matter involvement (14). In these cases, the diagnosis can be more challenging.

DISEASE COURSE

The course in more than 93% to 98% of pediatric MS cases (5) is characterized by relapses and remissions. Relapses are defined as the development of new neurological symptoms and signs lasting at least 24 hours that subsequently improve or stabilize. A progressive course without relapses is rare and usually suggests an alternative diagnosis. Over time (sometimes decades), most children with MS accumulate neurological impairments. However, this progression occurs more gradually in children than in adults with the disease (12,13). Less commonly, pediatric MS can have an aggressive course, and severe deficits during childhood can develop (15).

The classification of MS subtypes refers to the different patterns of the disease course. Although this classification was developed for adult MS cases, it also applies to pediatric ones. The relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) subtype is the most common type. Residual deficits may or may not develop from the relapse. Over time, most adults and children with MS will have a transition from a relapsing-remitting course to progression, defined as secondary progressive MS. During the progressive phase of the disease, patients simply insidiously and gradually accumulate increasing deficits. A much less common MS subtype—estimated in most series of children to occur in fewer than 3%—is primary progressive MS. In this subtype, no relapses occur at the onset, but instead, patients follow

a steadily progressive course from the beginning. In primary progressive MS, symptoms and signs accumulate over time, and relapses never occur. Another even more rare MS subtype is progressive relapsing MS. In these patients, the initial course is one of gradual progression; however, these individuals subsequently have occasional relapses, and such individuals are classified as having progressive relapsing MS.

a steadily progressive course from the beginning. In primary progressive MS, symptoms and signs accumulate over time, and relapses never occur. Another even more rare MS subtype is progressive relapsing MS. In these patients, the initial course is one of gradual progression; however, these individuals subsequently have occasional relapses, and such individuals are classified as having progressive relapsing MS.

Patients with relapsing-remitting disease will make a transition to a secondary progressive course at different rates. Among adults, the transition typically occurs 7 to 10 years after diagnosis. In contrast, children progress more gradually, and a secondary progressive form of the disease develops approximately 20 years after the diagnosis. During the same time period, in more than half of children with MS, permanent deficits will develop (8,12,13). Hence, the majority of children and adolescents will grapple with the more disabling aspects of their disease during young adulthood. However, compared with an adult onset, those with a pediatric onset will have permanent deficits, including inability to ambulate independently, at a significantly younger age (2,8,12,13).

Prognostic Factors

It is extremely difficult to predict the disease course in any one individual child or adult with MS. Some individuals show minimal signs of the disease throughout their course and experience few relapses. Others relapse frequently and rapidly progress to requiring a wheel chair.

Some features help to determine whether, at the time of a child’s first demyelinating event, a likelihood of a subsequent event exists. Risk for the development of subsequent relapses—making a diagnosis of MS much more likely—was addressed in a prospective study of 168 children who had their first demyelinating event. An increased risk for a subsequent event was found if the initial event was optic neuritis or if the child was older than 10 years (16). A decreased risk for a second event was noted in children first seen with spinal cord symptoms or alteration in mental status (16).

The factors predicting the disease course can be more difficult to define than those features associated with a second clinical episode. Those with an initial progressive course without any associated relapses (primary progressive MS) consistently do worse than those with a relapsing-remitting course (12,13,17). Studies of adults with MS have identified prognostic features related to relapses and development of impairments. The degree of recovery from the initial event, time to the second event, and the number of clinical events in the first 5 years have been identified as prognostic indicators of subsequent disability (18). Among children, besides a progressive course at onset, female gender, short interval between the first and second attacks, clinical symptoms of sphincter dysfunction, number of relapses within the first 2 years, absence of encephalopathy, and typical MS MRI findings predict more-pronounced disease (12,13,17,19). Although factors can be linked to more or less severe disease, for any one patient it is extremely difficult to predict the subsequent course.

Psychosocial Features

BEHAVIORAL ISSUES

Many aspects of pediatric MS pose challenges to families beyond those associated with chronic illness. The condition is rare, its course is uncertain, its manifestations are unpredictable and varied, and therapies are incomplete. Behavioral problems include denial,

difficulty with family and peers, and noncompliance with therapy (20). A further concern is that perceived stress can increase the probability of another MS relapse (21).

difficulty with family and peers, and noncompliance with therapy (20). A further concern is that perceived stress can increase the probability of another MS relapse (21).

Young people with MS or other chronic diseases may be at a particularly high risk for additional psychological problems (22) because of the effects of the disease on the brain, as well as the psychological reaction to the chronic illness. In adults with MS, depression is associated with an increased lesion burden in the inferior-medial frontal-temporal areas (23). Similar findings might be expected to apply to children with MS.

AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

In our experience of 13 children with MS, unselected for psychiatric illness and who underwent psychiatric interviews, six (46%) had affective disorders including major depression, anxiety disorder, and panic attacks. Much more information on psychiatric complications of MS comes from studies of adults. All show that affective disorders are frequent (24) and are more common compared with other neurological diseases with similar levels of disability.

More than 25% of adults with MS from community samples have depression (25). The lifetime prevalence of major depression in clinical samples is even higher—approximately 40% to 50% (26,27). Although more studies have addressed the depression associated with MS, anxiety disorders are another frequent and disabling problem. In various samples, 34% have anxiety, and 25% need treatment for it (24).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree