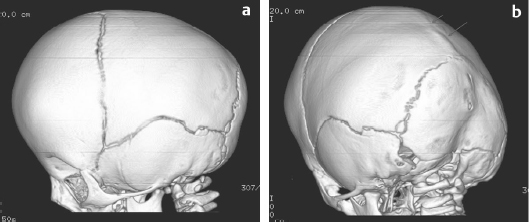

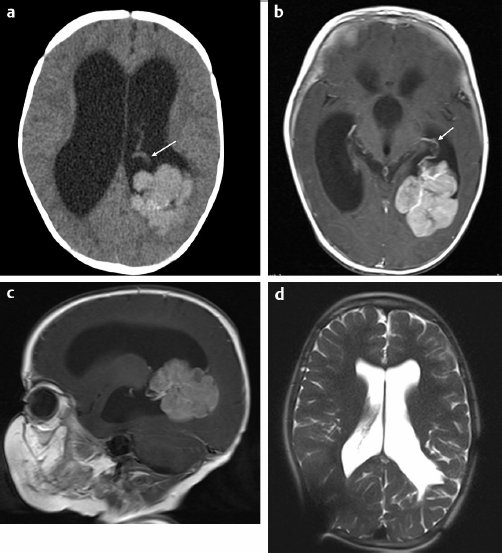

29 Anticoagulation management is not typically an important aspect of pediatric neurosurgical care. However, pediatric patients face significant risk with regard to blood loss issues related to weight and resultant blood volume and to immaturity of the hematopoietic system.1 This chapter presents specific cases to highlight strategies used to reduce blood loss and minimize allogeneic blood transfusion.2 The format for each case is standardized to illustrate the common themes for these clinical situations. For each case, a short discussion explains the course of action and provides other reasonable management options for similar circumstances. A 6-month-old boy was referred to the craniofacial clinic for assessment of craniosynostosis. The child was otherwise well with a normal physical examination except for head shape features consistent with sagittal synostosis. The referring physician had ordered a computed tomography (CT) scan of the head, which confirmed the diagnosis of sagittal synostosis (Fig. 29.1). It is not usual practice to do CTs when the clinical diagnosis is straightforward. However, the figures illustrate the head shape features and the fused sagittal suture. Surgery was offered to correct the calvarial deformity. Preoperatively, the child weighed 8.3 kg and had a preoperative hemoglobin of 12.2 g/dL with an estimated blood volume of 660 mL. Platelet count, international normalized ratio (INR), and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) were all normal. Directed donor blood was not done for the procedure. The intraoperative plan for potential transfusion was reviewed with the anesthesiologist. Two intravenous (IV) lines (one a central line) and an arterial line were inserted. Hypervolemic hemodilution was initiated with crystalloid solution.3 The threshold for transfusion was set for at a hemoglobin of 6 to 7 g/dL depending also on physiological parameters (blood pressure, heart rate, central venous pressure [CVP], and urine output). A 10% blood volume loss would result from 65 mL of blood loss. The operating room was kept warm until the child was fully covered and a warming blanket was functioning. Normothermia was carefully maintained throughout the procedure. Measurement of blood loss was accomplished with monitoring of suction and weighing of all surgical sponges. Fig. 29.1a,b (a) A three-dimensional (3D) computed tomography (CT) scan of the head showing the left side of the skull with patent coronal, lambdoid, and squamosal sutures. Frontal bossing is present. (b) A 3D CT scan of the head showing view of left posterior lateral aspect of skull with patent coronal, lambdoid, and squamosal sutures. Synostosis of the sagittal suture is evident by the ridging (arrows). The surgical procedure involved a bicoronal incision with a bifrontoparietal craniotomy followed by multiple barrel stave temporal bone cuts, remodeling of the bone before reattachment, and resultant cranial anteroposterior (AP) shortening using resorbing plates. Meticulous attention was paid to bleeding during the procedure. The scalp incision was done with scoring of the skin followed by use of monopolar (with a needle tip) and bipolar cautery to divide the subcutaneous tissue and control scalp bleeding. Bone bleeding was controlled with bone wax, frequently using the monopolar cautery to score the bone to help the bone wax adhere. One small bur hole was used for access, and the bifrontoparietal craniotomy was performed. Bone edge bleeding was controlled with bone wax. Dural oozing was dealt with using Surgicel, surgical patties, and Gelfoam, and warm, wet lap sponges. Scalp closure was accomplished with resorbing galeal and skin sutures. Intraoperative assessments of the child’s hemoglobin were 9.2 and 8.9 (above threshold for transfusion). Postoperative hemoglobin was 7.0 on day 3, but the child was well, with normal physiological parameters. Transfusion was not required. Postoperative iron supplementation (for 2 month duration) was started at the time of discharge from hospital. The patient underwent a surgical procedure that has low potential for significant blood loss but high probability of requiring a blood transfusion. It is the responsibility of the pediatric neurosurgeon to discuss with the anesthesiologist the potential for blood loss and the measures that are required to minimize blood loss so as to minimize the need for allogeneic blood transfusion and to establish a transfusion threshold to avoid unnecessary blood transfusion. Hypervolemic hemodilution was undertaken prior to starting the procedure. This does not affect coagulation but may reduce the total amount of red blood cell loss. It is equally important to discuss transfusion thresholds with the pediatric intensive care unit (ICU) physicians to avoid unnecessary blood transfusions. This child was also given iron supplementation after discharge to facilitate replenishment of iron stores. Strategies that were not undertaken in this case include the use of antifibrinolytics or a cell saver.4 Although an argument could be made for the use of an antifibrinolytic, it is not routine practice for this type of surgery at our institution. Cell savers are problematic in children of this size where the significance of the amount of blood loss is directly related to the small total blood volume that is at risk and because there is a small potential for catastrophic hemorrhage; typically more blood is collected in patties and sponges than with suction. In addition, in a younger child, it may have been feasible to do an endoscopic cranial vault remodeling, which entails a shorter duration of surgery and potentially less blood loss. A 5-year-old girl presented with an exacerbation of a slowly progressive 3-month history of headache with morning vomiting and lethargy. She had no other relevant past medical history. She was sleepy but would awaken with stimulation. She had a right cranial nerve VI partial palsy and bilateral papilledema. There was no focal motor weakness. She was ataxic but able to walk independently. A head CT scan demonstrated significant hydrocephalus with a large hyperdense lesion/tumor in the left posterior lateral ventricle with evidence of a large feeding vessel (Fig. 29.2a). A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan provided additional information regarding the lesion. The tumor was densely enhancing and was associated with multiple feeding vessels, with the largest located anterior to the tumor representing choroid vessels and evidence of large vessels within the tumor (Fig. 29.2b,c). The presumptive diagnosis was that this most likely represented a choroid plexus carcinoma or less likely a choroid plexus papilloma. MRI of the spine did not identify and evidence of tumor. Urgent surgery was recommended. Decadron was administered. A consultation was undertaken with a neuroradiologist to determine if any opportunity existed for preoperative embolization, but this was not felt to be a feasible option in this patient. Preoperatively, the child weighed 18.5 kg and had a preoperative hemoglobin of 14.2 g/dL with an estimated blood volume of 1,500 mL. Platelet count, INR, and PTT were all normal. The intraoperative plan for potential transfusion was reviewed with the anesthesiologist. Two IVs (one a central line) and an arterial line were inserted. Hypervolemic hemodilution was initiated with crystalloid solution and colloid solution. Tranexamic acid was administered preoperatively. The threshold for intraoperative transfusion was set at a hemoglobin of 7 g/dL depending also on the rate of blood loss and physiological parameters (blood pressure, heart rate, CVP, and urine output). A 10% blood volume loss would result from 150 mL of blood loss. The operating room was kept warm until the child was fully covered and a warming blanket was functioning. Normothermia was carefully maintained throughout the procedure. Measurement of blood loss was accomplished with monitoring of suction and weighing of all surgical sponges. Fig. 29.2a–d (a) Axial unenhanced CT scan of the head demonstrating hydrocephalus and a large hyperdense posterior left lateral ventricular mass with a large vessel anterior to the mass (arrow). (b) Axial T1-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the head demonstrating hydrocephalus and a large hyperdense posterior left lateral enhancing ventricular mass with a large vessel anterior to the mass (arrow) and vessels traversing the tumor. (c) Sagittal T1-enhanced MRI scan of the head demonstrating hydrocephalus and a large hyperdense posterior left lateral enhancing ventricular mass with large vessels anterior to the mass. (d) Axial HASTE (Half-Fourier Acquisition Single Shot Turbo Spin Echo) MRI scan of the head done 5 years after diagnosis demonstrating stable ventriculomegaly, evidence of artifact from the right parietal shunt, and no evidence of tumor in the left lateral ventricle. Additional full MRI sequences with and without enhancement (spine and brain) demonstrated no evidence of any tumor recurrence.

Pediatric Neurosurgery–Specific Patient/Case Examples

Case 1: Craniosynostosis (Low Risk of Large Volume of Bleeding But High Risk of Transfusion)

History

Procedure

Discussion

Case 2: Brain Tumor with High Vascularity (High Risk of Large Volume of Bleeding and High Risk of Transfusion)

History

Procedure

Pediatric Neurosurgery–Specific Patient/Case Examples

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree