Sleep disorders are extremely common during childhood. Unfortunately, even with the prevalence of sleep problems and despite being either preventable or treatable, childhood sleep disorders often go underrecognized and undiagnosed. There are many reasons for this, but the fact remains that children are not receiving the attention they need when it comes to sleeping. Proper restorative sleep for children is critical for their development, and quality sleep for a child is just as important, if not more so, than it is for adults. Even though sleep disorders are prevalent in children, the majority of the literature regarding sleep testing primarily covers adult disorders. Despite the massive amount of research on pediatric sleep disorders, which grows by the day, the pediatric content in most sleep medicine textbooks receives very limited coverage. Published in 1968, A Manual of Standardized Terminology, Techniques, and Scoring System for Sleep Stages of Human Subjects standardized sleep stage scoring in adults; pediatrics was not addressed in the manual. In 1971, a committee cochaired by Drs. Anders, Emde, and Parmelee authored A Manual for Standardized Techniques and Criteria for Scoring of States of Sleep and Wakefulness in Newborn Infants. Not addressed in that publication were standards for evaluating sleep in older infants, toddlers, children, and preadolescents.

In the last few decades, standards for pediatric sleep testing have received increased attention. In 2007, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) published The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology, and Technical Specifications. This manual includes sections on sleep staging and respiratory rules for pediatric patients. In 2011, the AASM published Respiratory Indications for Polysomnography in Children: An Evidence-Based Review to help sleep specialists determine the appropriateness of ordering a sleep study in children. Standards for staging and scoring pediatric studies have evolved since 2007. With several revisions in the last few years and updated regularly, the AASM Scoring Manual is frequently redefining and issuing improved rules for pediatrics.

Sleep architecture changes significantly over the first two decades of life. Sleep patterns and sleep behaviors evolve and are modified by both “intrinsic” (e.g., normal development) and “extrinsic” (e.g., environment and parenting practices) processes as we progress from infancy to childhood and through adolescence. This chapter will discuss the developmental issues inherent when performing pediatric sleep studies as related to both sleep staging and respiratory event scoring. It will review the current

scoring rules implemented by the AASM and how to apply these rules for pediatric patients. This chapter will focus on differences between adults and children as they apply to performing and scoring pediatric polysomnography. Techniques used to identify staging and events specific to children will be included. The goal is to provide an overall enhanced appreciation regarding the complexities involved with pediatric sleep scoring.

THE PEDIATRIC DIFFERENCE

Even though most of what is written about sleep medicine concerns adults and their disorders, children experience the same broad range of sleep disorders encountered in adults, including sleep apnea, insomnia, parasomnias, delayed sleep-wake phase disorder, narcolepsy, and restless legs syndrome. In fact, a pediatric sleep center will encounter a diverse population of disorders on a more regular basis than the typical breathing and arrhythmia disorders seen in an adult sleep center. Sometimes labeled the same in adults and children, the clinical presentation, evaluation, and management of some disorders may differ significantly. For example, an adult with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) may present with excessive sleepiness and lethargy, whereas a child with OSA could present with hyperactivity and restlessness, sometimes labeled incorrectly as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Although snoring and sleep apnea are common indications for referral to a sleep specialist, many children also have a behavioral or nonrespiratory sleep disorder either as another comorbid diagnosis or as a primary sleep disorder. In addition and similar to adults, children are increasingly prescribed medications that affect their sleep, making treatment more complicated (

1).

Scoring pediatric sleep studies is a challenging experience, but so can be performing sleep studies on pediatric patients. Most adult sleep centers are not properly suited to treating young children. A pediatric sleep center needs an atmosphere designed with the child in mind. There should be child-pleasing surroundings and decorations that help soothe and distract. Well-trained sleep center staff are necessary to care for the pediatric population. To be prepared, staff must be well informed regarding the variances in development not only physically, but also mentally with the age and medical condition of each patient. Competent pediatric sleep technologists understand proper distraction techniques, and they are provided the tools needed to perform this function well for each patient. It is also helpful to have the parent or caregiver involved to make the testing go smoothly. There should be accommodations for the parent or caregiver to stay in the room with the child. Furthermore, consider the testing equipment. It is best if the monitoring equipment is contained outside the bedroom or in a cabinet hidden from view, as it can seem intimidating to a child. As much as possible, keep equipment and supplies away from the reach of the curious child.

The physical and anatomic differences between younger children and older adults are obvious, but also consider mental development before performing a sleep study. It is best practice to have the child seen by a pediatric sleep specialist who can review the history and symptoms in a clinical setting. The sleep specialist has the opportunity to assess for and prioritize the various sleep concerns before ordering appropriate testing. Pediatric sleep studies can be “customized” on the basis of the child’s symptoms. An enuresis alarm, esophageal pressure monitoring, pH recording, and seizure montage are some of the additional monitoring tools often added for pediatric testing. At this time, it may be determined that a sleep diary or actigraphy monitoring is essential to collect additional information on sleep behavior. Some children and their families find it helpful to visit the sleep center before the actual study. This is often possible during the clinic visit and should be encouraged. Making the surroundings friendly and familiar to the child increases compliance during the night of the study.

It is best practice to have a prescreening tool in place to assess the child’s needs and developmental level. Information gathered at the clinic visit and during the scheduling portion is helpful in predicting what to expect on the night of the study. By the day of the study, staff should be aware of the patient’s needs for testing and preparation in staffing adjusted so it is appropriate for difficult or medically complex children. On the night of the study, schedule the family to arrive at the sleep center early enough so that the study begins as close as possible to the child’s normal bedtime. Children are encouraged to bring any favorite toys, pillows, and even videos that will make their stay in the sleep center more comfortable. To help children and parents feel more comfortable, show them the area where the parent or caregiver is to stay overnight. During the stay, involving the parent or caregiver as much as possible will enhance the experience of the child and create a more peaceful experience.

Many adult sleep centers have a protocol of performing a split-night test, in which the first part of the night is diagnostic to determine if the patient has sleep-disordered breathing or other events affecting sleep. If the study uncovers events that warrant positive airway pressure (PAP) treatment, then a titration study is performed the second part of the night. In pediatrics, there is a concern that a shortened study may underestimate the degree of sleep-disordered breathing in children. Most often, respiratory events increase in frequency or become more severe as the night progresses and the child spends more time in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. It is highly recommended to perform a baseline study for an entire night to get a full appreciation of the

child’s sleep-disordered breathing. In addition, from a practical standpoint, many children with OSA do not require PAP treatment. Instead, children with sleep apnea typically receive referrals to an otolaryngologist for consideration of an adenotonsillectomy. If it is decided that a titration study is needed, it will be performed on another night, preferably after the child has undergone a desensitization period with the PAP mask. Then when the child returns for his or her PAP study, it will allow the technologist a full night to properly titrate the patient and find the correct pressure.

Proper application of the electroencephalogram (EEG) electrodes and other monitoring leads is critical to acquiring a quality sleep study in children, and it lays the foundation for quality scoring. There are many techniques available to help the child feel comfortable and be cooperative while applying electrodes. In spite of this if the child adamantly refuses to allow the sensors to be applied, the technologist may, depending on the type of study to be performed, allow the child to first fall asleep without applying the full montage. At times, adding the additional electrodes and sensors after the child has entered deep delta sleep results in better impedances, improving the quality of the study collected for scoring.

Performing patient calibrations is another important step in performing quality sleep studies and aids the technologist in proper scoring. Because of their lack of a clear alpha pattern, it is especially important to obtain a lengthy sample baseline of wake EEG in children. This recording portion is helpful during staging of the study as a reference to aid in determining wake versus sleep. Calibrations can be difficult, if not impossible, in the noncompliant or very young child. There are a variety of methods that can be used depending on the situation. One technique to obtain calibrations in this population is with the assistance of another technologist or parent. For instance, to check electrooculogram (EOG) waveforms, the assistant or parent can move an object back and forth for the child to track with the eyes, and leg movement calibrations can be done with the assistant flexing the child’s foot when instructed.

One important respiratory measurement collected routinely in pediatric studies and typically not recorded in adult studies is carbon dioxide (CO2) monitoring obtained through either end-tidal CO2 nasal cannula or placement of a transcutaneous CO2 monitor. Because of airflow concerns, using transcutaneous CO2 monitoring at times may be more beneficial, especially with infants or children on positive pressure ventilation. In addition to providing another assessment of air exchange, end-tidal CO2 measurements allow for the detection and quantification of hypoventilation, often more commonly seen in children than in adults.

IDENTIFYING SLEEP STAGES IN INFANTS AND CHILDREN

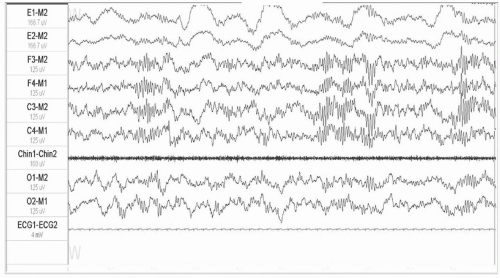

Newborn infants or neonates do not have the fully developed sleep stages as those seen in adults. Infants have a

dominant posterior rhythm (DPR) EEG pattern slower than that seen with adults who have an 8- to 13-Hz alpha rhythm (

Fig. 61-1). The DPR in most normal children develops as they grow, changing from a 3.5- to 4.5-Hz

rhythmic activity at 3 to 4 months postterm to a 5- to 6-Hz activity by 6 months of age. EEG activity is generally 7 Hz by 1 year of age. Vertex sharp waves develop at 2 months and are more noticeable in children after the age of 3. Sleep spindles can be seen by 2 months postterm. K-complexes seen as early as 3 months are usually present by 6 months of age, as is slow-wave activity. At 2 years of age, both sleep spindles and K-complexes appear similar to those seen in adults. Infants 2 months or older postterm typically can be staged using W, N1, N2, N3, and R stages (

Table 61-1) (

2,

3).

There is a period when some infants will not have developed all the well-defined characteristics of nonrapid eye movement (NREM) sleep stages as seen in N1, N2, and N3. Sleep spindles, K-complexes, or slow-wave sleep may not be easily recognizable in the EEG waveform for these infants. During this time, the epochs that do not meet the criteria for stages W, N1, N2, or N3 are scored as stage N (NREM). The rules state that if all the epochs of NREM sleep in an infant study show no sign of sleep spindles, K-complexes, or high-amplitude slow-wave sleep, then score all these epochs as stage N. If there are any epochs that have sleep spindles and K-complexes, score these epochs as stage N2. If some epochs contain more than 20% slow-wave activity, score these as stage N3, and otherwise score the NREM sleep as stage N (

4).

Scoring Sleep Stages

Although EEG characteristics will be different because of the age of the patient, sleep staging in pediatrics follows the adult rules for stages N2, N3, and R. One difference in children will be the greater amount of high-amplitude slow-wave sleep, especially in younger children. Slow-wave sleep decreases as we age. Compared with the preteen child, there will be a noticeable reduction in slow-wave activity as the child ages into his or her late teenage years and beyond. Younger children entering sleep will show a slowing of their DPR and will often have hypnagogic hypersynchrony or theta activity. Unless there are events causing disturbances either from the patient or externally, children do not stay in stage N1 for long periods. Within minutes, they progress into deeper stages of sleep. The younger the child, the sooner this tends to happen.

Sleep staging in children is similar to that of adults, except that the younger child will have a slower DPR or baseline pattern. The DPR indicates wakefulness and it varies from child to child because of the wide range of maturity levels seen in a pediatric sleep center. Again for this reason, patient calibrations used as a reference can be extremely helpful in determining what pattern of EEG is predominant in the wakeful child (

Table 61-2).

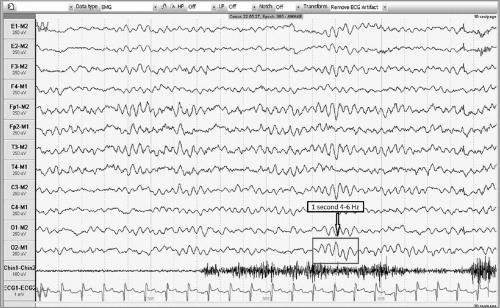

Once you are comfortable with recognizing the DPR wakefulness EEG pattern in your patient, look for a slowing and attenuation or lowering of amplitude in the EEG waveform to detect sleep onset. If you see this change in waveform pattern for more than 50% of the epoch, then score that epoch as stage N1. To further help recognize the beginning of stage N1 or sleep onset, watch closely for the EEG waveform to become clearer and sharper as artifact is decreased or drops out as the child relaxes upon entering sleep. This is seen more noticeably in infant polysomnography and, along with other signs, can indicate relaxation into sleep (see

Fig. 61-2 that determines sleep and sleep hypnagogic hypersynchrony).