Perinatal psychiatry

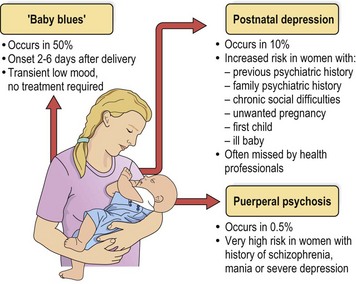

Perinatal psychiatry involves the recognition, assessment and management of mental disorders during pregnancy and the postnatal period. Traditionally, the focus has been on the period following delivery, during which there is a raised risk of depression and psychosis, and it is the postnatal conditions, outlined in Figure 1, that will be discussed in detail here. However, mental illness also occurs during pregnancy and, when present, will often persist postnatally.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree