11 Peripheral neuropathy

Introduction

Ability to differentiate between upper motor neurone (UMN) and LMN damage is fundamental to understanding PN (see Table 11.1). Cranial nerves represent a special type of peripheral nerve emanating from the brainstem. This raises an ‘old chestnut’, namely facial weakness of either UMN or LMN origin.

TABLE 11.1 Differentiation between upper motor neurone and lower motor neurone damage

| UMN | LMN | |

|---|---|---|

| Inspection | Limited or no loss of muscle bulkNo fasciculations | Localised or generalised muscle wastingFasciculations may be present |

| Tone | Increased muscle tone (clasp knife) | Decreased tone consistent with loss of bulk |

| Power | Decreased power in distribution of UMN (antigravity muscles) | Weakness of muscles innervated by damaged nerves |

| Reflexes | Increased (brisk) reflexes below level of damageUp going or splaying of toes | Decreased or absent reflexes in muscles denervatedToes down going |

| Sensation | Generally not affected | Decreased if sensory nerves also involved |

There are some conditions that may affect both UMN and LMN,1 such as motor neurone disease (often referred to as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) or subacute combined degeneration, as may occur with vitamin B12 deficiency.2

What follows in this chapter is a discussion of the nature of nerve damage, causes of PN, diagnosis thereof, a look at some focal neuropathies, nutritionally induced neuropathies and some illnesses associated with PN. The aim is to help general practitioners become more involved in patient care and, hence, better enjoy the therapeutic partnerships with the consultant.

The Nature of Nerve Damage

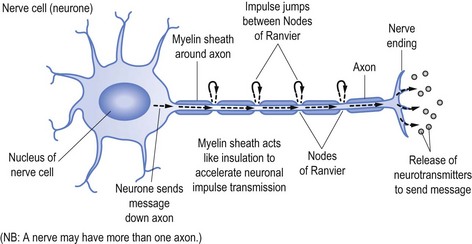

Nerves transmit their messages via an electrical impulse from the nerve cell (the cell of the neurone) down the length of the ‘arm’ of the cell (the axon) to pass the message either to another nerve or the end target organ. The message is sent via the impulse causing release of the neurotransmitters that produce the desired effect, be it to stimulate or suppress a subsequent response, such as causing a muscle to contract or to stimulate another nerve (see Fig 11.1).

To speed up transmission the axons of the nerves are usually coated with myelin, which acts in a similar fashion to the plastic coating that insulates and allows unimpeded passage of electrical current down an electrical wire (see Fig 11.1). Along the myelinated nerve fibre the impulse ‘jumps’ between Nodes of Ranvier, breaks in the myelin.

In the same way the wire within the plastic transmits the electrical current, so too does the axon send the neuronal impulse. It follows that damage to the axon (analogous to the electrical wire) will reduce the amount of message able to be transmitted. In neurophysiological terms, axonal damage will reduce the amplitude of the impulse and hence the amplitude of the action potential generated,3 namely the size and strength of the message received rather than the speed of the transmission.

Transmission speed (or conduction time) is facilitated by the myelin sheath. It follows that damage to myelin, as occurs in demyelinating illnesses (such as Landry-Guillain-Barré syndrome, often referred to as GBS—omitting the name Landry, or multifocal motor neuropathy) will slow conduction time.4 In the same way damage to the plastic coating of the electrical wire will ultimately allow the wire to corrode and be damaged, so too will established demyelination allow subsequent axonal damage.5

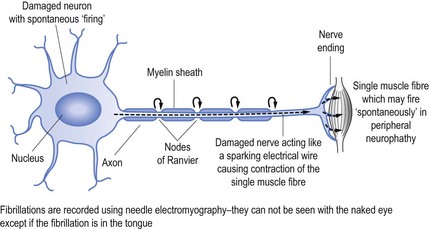

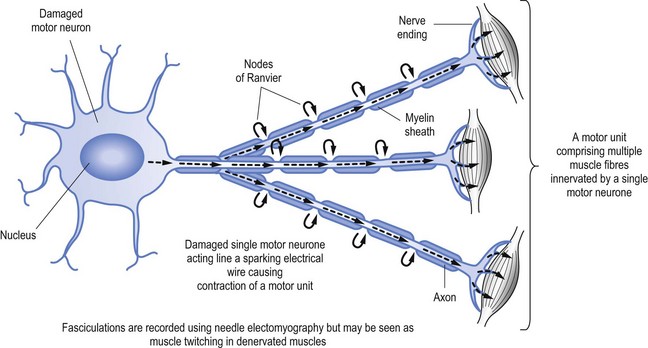

When nerves are damaged it may be akin to a short circuit, to continue the electrical wire analogy. Thus nerves may ‘fire’ spontaneously. This may result in the activation of a single muscle fibre (called fibrillation, see Fig 11.2) or a group of muscle fibres known as a motor unit, which is limited to muscle fibres innervation by a single motor nerve (called fasciculation, see Fig 11.3).

Causes of Nerve Damage

PN can be the result of either local damage or a more generalised process affecting a wider target (see Box 11.1).

Box 11.1 Treatable causes of peripheral neuropathy

Dietary deficiency neuropathies:

Heavy metals, such as lead or mercury poisoning

Neurotoxic drugs, such as nitrofurantoin

Landry-Guillain-Barré syndrome

Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP)

The most common cause of local damage is consequent to pressure, which causes a ‘neurapraxia’ that damages the nerve at the site of the pressure. An example of this process is damage to the lateral popliteal nerve with resultant foot drop. The lateral popliteal nerve activates the tibialis anterior muscle that dorsiflexes the foot.6 Similarly, direct damage to the radial nerve as it transverses the humeral groove in the humerus bone will result in wrist drop due to deficits of wrist extension.7

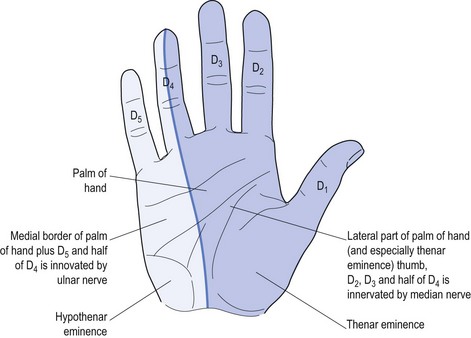

Perhaps the best-known local nerve damage is carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), which affects the median nerve. This causes weakness of the muscles innervated by the nerve plus specific sensory deficit referable to local median nerve damage (see Fig 11.4).

Only four intrinsic hand muscles are innervated by the median nerve.8 The remainder are innervated by the ulnar nerve. There is a mnemonic to remember these four muscles: LOAF (Lateral two lumbricals, Opponens pollicis, Abductor pollicis brevis and Flexor pollicis brevis).

Generalised PN results from a systemic problem that can be the result of a variety of toxins, for example drugs (e.g. vincristine)9 or infections, which may be the precipitant for conditions such as motor neuropathy (as may occur with infectious hepatitis)10. A variety of other environmental toxins, such as lead and other heavy metals,11 can also cause pure motor neuropathy.

Conditions such as Landry-Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS, also known as idiopathic ascending inflammatory polyradiculopathy)12 and chronic inflammatory demyelinating neuropathy13 (CIDP) represent allergic responses to reputed infective agents causing demyelinating radiculopathy or neuropathy.12,13

Diagnosis of Nerve Damage

a History

Many patients with PN will start with the complaint of numbness, so clarification is important. Having confirmed that both doctor and patient understand the meaning relevant to the particular patient, the next step is to define the exact distribution of the sensory change(s). Specific nerve damage should cause a typical distribution of sensory change (see Fig 11.4) but often patients find it impossible to be specific. Often patients with CTS will report waking at night and state ‘my whole hand went to sleep’. They have trouble differentiating between palm and dorsum of the hand, and most will not recognise the anatomic ‘splint’ affecting the ring finger (see Fig 11.4). Some may report that the whole arm, meaning the whole upper limb, was affected and some may confuse the picture by stating that it started in the shoulder and passed to the hand, or started at the elbow.

Some additional considerations to be included in the history taking include: any identifiable causative factors; knowledge of any pre-existing diagnoses (such as diabetes discussed earlier); relevant family history (such Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease for hereditary neuropathies); exposure to medications; nutritional status (such as vegans not ingesting sufficient vitamin B12); excessive alcohol consumption (with direct alcohol toxicity or dietary deficiencies such as vitamin B1); and a comprehensive systems review (that may reveal conditions such as vasculitis, sarcoidosis or exposure to heavy metals such as lead or mercury, being recognised occupational hazards, or cytoxic or radiologic treatment for neoplasia).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree