Chapter 7

Person-Centred Care

Personhood in dementia

The progressive cognitive impairments that are the hallmark of dementia sometimes make it appear to others that the person is disappearing as the disease progresses. Since the seminal theoretical work of Kitwood in the 1990s, a person-centred approach for understanding the experience of dementia is advocated and has been demonstrated to have a positive impact on well-being. PCC rests on a value base that recognises the personhood of all persons regardless of age or cognitive ability. This challenges the assumption that dementia is the death that leaves the body behind. It requires that those living with dementia are treated as individuals, recognising that all people have a unique history and personality. It also requires that the perspective of the individual is seen as the starting point for care and that empathy with this perspective has its own therapeutic potential. People living with dementia need an enriched social environment that compensates for their impairment and fosters opportunities for ensuring that they have chances for closeness to others. People with dementia have a continuing capacity to experience relative well-being and ill-being, and this is strongly influenced by the behaviour of others towards them – the psychosocial milieu (Figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1 Who do you see when you are asked to assess a patient with dementia?

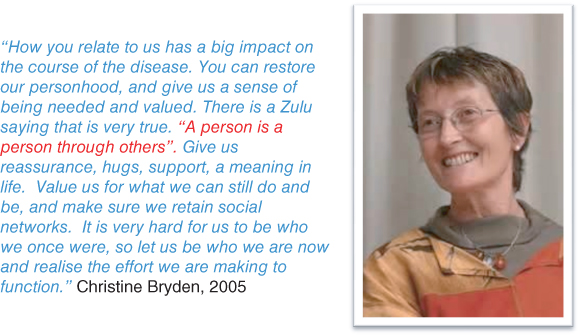

Although cognition fails, there are numerous accounts of the person’s need for warm human contact if a state of well-being is to be achieved. With the onset of dementia, individuals are very vulnerable to their psychological defences being broken down. As the sense of self breaks down, it becomes increasingly important that it is reinforced by others through the relationships the person with dementia experiences (Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.2 One of the richest accounts of what it is like to live with dementia comes from the Australian writer Christine Bryden who was diagnosed with dementia at the age of 46.

Malignant Social Psychology

Kitwood described personhood as being undermined when individual needs and rights are not considered, when powerful negative emotions are ignored or invalidated and when increasing isolation from human relationships occurs. He used the phrase Malignant Social Psychology (MSP) as an umbrella term for such episodes, using terms such as intimidation, outpacing, infantilisation, labelling, disparagement, blaming, manipulating, invalidating, disempowering, overpowering, disrupting, objectifying, stigmatising, ignoring, banishing and mocking to illustrate the many ways that personhood can be undermined in non-person-centred care environments. MSP is rarely done with malicious intent. It can become interwoven into the care culture within some organisations and can easily take hold unless constant effort is made to keep it at bay. New staff learn from existing staff how to communicate with people with dementia. If the staff communication style is one that is characterised by the infantilisation and outpacing of people with dementia, then the new staff member is likely to follow this lead. The malignancy in MSP is that it eats away at the personhood of those being cared for and it also spreads very quickly from one member of staff to another. High levels of challenging behaviour, distress or apathy occur more commonly in care situations that are not supportive of personhood.

Positive person work

Personhood can be supported by positive interactions such as those that feature recognition of the person, negotiation, collaboration, a sense of fun, creativity, engagement through the senses, celebration, relaxation, validation, holding, facilitating and enabling the person to be engaged in life. We know that skilled person-centred care and support early on in dementia (such as individualised family assessment, skills training, information, counselling and support) delays care-home admission and improves caregiver mood. We know that skilled person-centred care and support minimises the escalation of problems into behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). In care homes, we know that people with dementia have better mood and quality of life if they are cared for by staff who communicate well and that staff who are trained in person-centred care decrease agitation levels in high-dependency care-home residents. Sensitive engagement in interaction and personalised activities decreases levels of agitation and ill-being.

Communicating well with people living with dementia

Most of the interventions we make with people with dementia and their families do not rely on the prescription of medication. They rely on good communication. People with dementia face particular challenges in having their voice heard. The cognitive impairment associated with dementia often affects memory function, the ability to use and understand spoken and written language, the ability to carry out practical everyday tasks, the ability to perceive the world as others do or the ability to plan a course of action. Although there is a decline in cognitive abilities, there is no decline in depth of feeling or the range of emotions that people with dementia experience. Indeed, in many situations, emotions appear stronger than ever. Anger, joy, grief and excitement are often easily accessed. Being aware of the pattern of cognitive deficits and the strength of emotions is a key ingredient in PCC because it enables health care professionals to use communication skills to respond appropriately to individual patients. The aim is to find a response that supports the person with dementia while not undermining their remaining abilities.

Health care professionals can do a great deal to provide the structure that people with dementia need in order to communicate, even when time is limited. The approach to communication will depend on the level and type of cognitive impairment. Some people – particularly early on in their dementia – may have very little problem communicating. It may be enough that the health professional is mindful of summarising regularly, checking out understanding and providing assistance to keep people on track. Other people with much more advanced dementia may have virtually no language at all. In these situations, the person will need a lot more help to ensure their ‘voice’ gets heard. Many people will fall between these two extremes and the ability to communicate is often sensitive to factors other than the dementia. Factors such as tiredness, lack of hydration and acute illness will have a much bigger impact on communication skills in a person struggling with cognitive impairment. Noisy environments and poor lighting will further exacerbate difficulties. Also, if English is a second language, this often deteriorates more quickly than the mother tongue; therefore, communicating in the correct language is important.

As verbal communication becomes more difficult, attending carefully to the non-verbal behaviour or piecing together fragmented speech becomes increasingly important.

Striking up a good rapport is often not dependent on verbal skills. As verbal abilities are lost, the importance of respectful, warm, accepting human contact through non-verbal channels becomes even more important. Courtesy, respect, friendliness and kindness are usually communicated by non-verbal actions and tone of voice. Also, people with dementia may be more aware of any mismatch between what is being communicated verbally and non-verbally, because of their stronger reliance on non-verbal communication. For example, if the health professional looks annoyed or off-hand in body language or facial expressions, this is what a person with dementia will notice, even if the words are saying something very different (Figure 7.3).

Figure 7.3 Is the communication style indicative of Malignant Social Psychology or Positive Person Work? Think about your own practice and the services with which you work.

The challenge of providing person-centred care

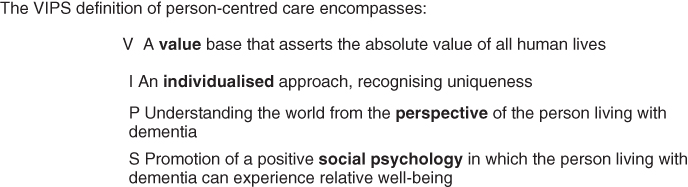

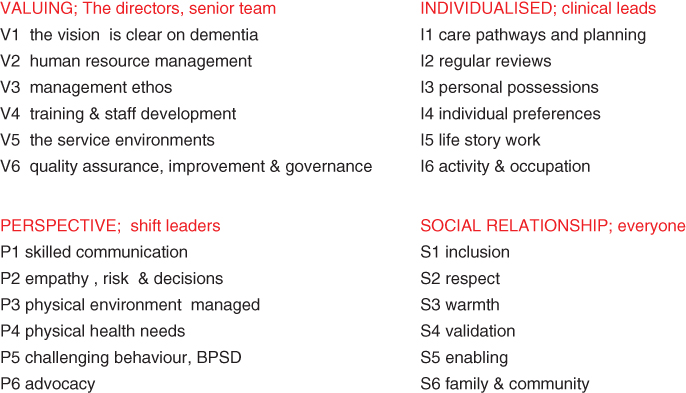

The concepts in PCC are not easy to articulate and can feel difficult to translate into everyday practice. The VIPS definition of person-centred dementia care attempts to synthesise the different threads of PCC whilst maintaining the sophistication of Kitwood’s original theories. This can be summarised in the equation PCC = V + I + P + S. This equation does not give a pre-eminence of any element over another, just that they are all contributory. It also reminds us that we are providing care for very important persons (Figure 7.4).

Figure 7.4 The VIPS definition of person centred care (Brooker, 2007).

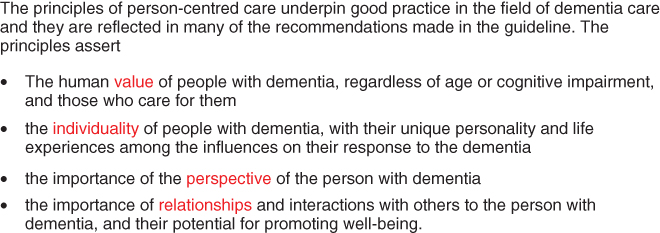

The VIPS definition was used in the NICE/SCIE guidelines on dementia (Figure 7.5).

Figure 7.5 NICE clinical guidelines on Dementia: Supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care.

The VIPS elements can be used as general guiding principles for health care practitioners to reflect on their interactions with people with dementia and their families. Reflective questions include the following:

- Does my behaviour and the manner in which I am communicating with this person show that I respect, value and honour them?

- Am I treating this person as a unique individual?

- Am I making a serious attempt to see my actions from the perspective of the person I am trying to help? How might my actions be interpreted by this person?

- Does my behaviour and interactions help this person to feel socially confident and that they are not alone?

These principles apply in every situation when health care professionals communicate. They apply when giving someone an injection, helping a person use the toilet, assisting a person to complete an advanced care plan or in running a reminiscence group. It is not the task that is person-centred but the way in which that task is done that can make it person-centred or not.

The whole organisation approach

Providing care in a humanistic and person-centred way that really aims to value people living with dementia is a challenge, particularly in care homes and hospitals where frontline care staff themselves may not feel their own personhood is valued. High-level staff turnover, staff shortages and poorly trained staff lead to negative quality of life for care-home residents. Staff who feel demoralised, burnt out and stressed are unlikely to be able to take the care to communicate in the respectful, warm and inclusive way that is required in person-centred care. To achieve person-centred care as part of regular care in care homes and hospitals demands the involvement of staff at all levels of the organisation. The VIPS framework provides a checklist of 24 indicators that care providers can use as a benchmark to assess the person-centredness of their service. This provides concrete examples of the practice that should be in place within any care organisation that claims to provide person-centred dementia care (Figure 7.6).

Figure 7.6 The VIPS framework for implementing person-centred care across a whole organization. Leadership at different levels is required to ensure the building blocks and structures are in place to support the delivery of personn-centred care at an individual level.

Person-centred care requires sign-up to working in this way across the whole care provider organisation if it is to be sustained over any length of time. Particular elements require leadership at different levels. Valuing requires leadership from those responsible for leading the organisation at a senior level. Individual care requires leadership, particularly from those responsible for setting care standards and procedures within the organisation. Perspectives and social environment require leadership for those responsible for the day-to-day management and provision of care. This is also available as a free website (www.carefitforvips.co.uk), which enables care-home providers to assess how well they are delivering care against the 24 indicators and helps them identify priorities for improvement. It also contains extensive information and resources covering all aspects of person-centred dementia care alongside online quality improvement cycles to plan, test and record ideas for improvements.

Finally, a word about labels

Health care professionals sometimes have a habit of using labels to describe people.

Although not intentional, this can promote the sort of malignant social psychology that Kitwood wrote about all those years ago as undermining personhood. Referring to people as bed blockers, wanderers, shouters or dements undermines the humanity of people who are using health care. Even terms such as the elderly (rather than older people) or dementia sufferers (rather than people living with dementia) promote a certain image that most people would prefer not to be associated with. The language that is used by health care professionals has a powerful impact on those living with dementia, their families and other staff involved in care.