Personality Disorders

The understanding of personality and its disorders distinguishes psychiatry fundamentally from all other branches of medicine. A person is a self-aware human being, as C. Robert Cloninger said, not “a machine-like object that lacks self-awareness.” Personality refers to all of the characteristics that adapt in unique ways to ever-changing internal and external environments.

Personality disorders are common and chronic. They occur in 10 to 20 percent of the general population, and their duration is expressed in decades. Approximately 50 percent of all psychiatric patients have a personality disorder, which is frequently comorbid with other clinical syndromes. Personality disorder is also a predisposing factor for other psychiatric disorders (e.g., substance use, suicide, affective disorders, impulse-control disorders, eating disorders, and anxiety disorders) in which it interferes with treatment outcomes of many clinical syndromes and increases personal incapacitation, morbidity, and mortality of these patients.

Persons with personality disorders are far more likely to refuse psychiatric help and to deny their problems than persons with anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, or obsessive-compulsive disorder. In general, personality disorder symptoms are ego syntonic (i.e., acceptable to the ego, as opposed to ego dystonic) and alloplastic (i.e., adapt by trying to alter the external environment rather than themselves). Persons with personality disorders do not feel anxiety about their maladaptive behavior. Because they do not routinely acknowledge pain from what others perceive as their symptoms, they often seem disinterested in treatment and impervious to recovery.

CLASSIFICATION

The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) defines a general personality disorder as an enduring pattern of behavior and inner experiences that deviates significantly from the individual’s cultural standards; is rigidly pervasive; has an onset in adolescence or early adulthood; is stable through time; leads to unhappiness and impairment; and manifests in at least two of the following four areas: cognition, affectivity, interpersonal function, or impulse control. When personality traits are rigid and maladaptive and produce functional impairment or subjective distress, a personality disorder may be diagnosed.

Personality disorder subtypes classified in DSM-5 are schizotypal, schizoid, and paranoid (Cluster A); narcissistic, borderline, antisocial, and histrionic (Cluster B); and obsessive-compulsive, dependent, and avoidant (Cluster C). The three clusters are based on descriptive similarities. Cluster A includes three personality disorders with odd, aloof features (paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal). Cluster B includes four personality disorders with dramatic, impulsive, and erratic features (borderline, antisocial, narcissistic, and histrionic). Cluster C includes three personality disorders sharing anxious and fearful features (avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive). Individuals frequently exhibit traits that are not limited to a single personality disorder. When a patient meets the criteria for more than one personality disorder, clinicians should diagnose each.

ETIOLOGY

Genetic Factors

The best evidence that genetic factors contribute to personality disorders comes from investigations of more than 15,000 pairs of twins in the United States. The concordance for personality disorders among monozygotic twins was several times that among dizygotic twins. Moreover, according to one study, monozygotic twins reared apart are about as similar as monozygotic twins reared together. Similarities include multiple measures of personality and temperament, occupational and leisure-time interests, and social attitudes.

Cluster A personality disorders are more common in the biological relatives of patients with schizophrenia than in control groups. More relatives with schizotypal personality disorder occur in the family histories of persons with schizophrenia than in control groups. Less correlation exists between paranoid or schizoid personality disorder and schizophrenia.

Cluster B personality disorders apparently have a genetic base. Antisocial personality disorder is associated with alcohol use disorders. Depression is common in the family backgrounds of patients with borderline personality disorder. These patients have more relatives with mood disorders than do control groups, and persons with borderline personality disorder often have a mood disorder as well. A strong association is found between histrionic personality disorder and somatization disorder (Briquet’s syndrome); patients with each disorder show an overlap of symptoms.

Cluster C personality disorders may also have a genetic base. Patients with avoidant personality disorder often have high anxiety levels. Obsessive-compulsive traits are more common in monozygotic twins than in dizygotic twins, and patients with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder show some signs associated with depression—for example, shortened rapid eye movement (REM) latency period and abnormal dexamethasone-suppression test (DST) results.

Biological Factors

Hormones. Persons who exhibit impulsive traits also often show high levels of testosterone, 17-estradiol, and estrone. In nonhuman primates, androgens increase the likelihood of aggression and sexual behavior, but the role of testosterone in human aggression is unclear. DST results are abnormal in some patients with borderline personality disorder who also have depressive symptoms.

Platelet Monoamine Oxidase. Low platelet monoamine oxidase (MAO) levels have been associated with activity and sociability in monkeys. College students with low platelet MAO levels report spending more time in social activities than students with high platelet MAO levels. Low platelet MAO levels have also been noted in some patients with schizotypal disorders.

Smooth Pursuit Eye Movements. Smooth pursuit eye movements are saccadic (i.e., jumpy) in persons who are introverted, who have low self-esteem and tend to withdraw, and who have schizotypal personality disorder. These findings have no clinical application, but they do indicate the role of inheritance.

Neurotransmitters. Endorphins have effects similar to those of exogenous morphine, such as analgesia and the suppression of arousal. High endogenous endorphin levels may be associated with persons who are phlegmatic. Studies of personality traits and the dopaminergic and serotonergic systems indicate an arousal-activating function for these neurotransmitters. Levels of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), a metabolite of serotonin, are low in persons who attempt suicide and in patients who are impulsive and aggressive.

Raising serotonin levels with serotonergic agents such as fluoxetine (Prozac) can produce dramatic changes in some character traits of personality. In many persons, serotonin reduces depression, impulsiveness, and rumination and can produce a sense of general well-being. Increased dopamine concentrations in the central nervous system produced by certain psychostimulants (e.g., amphetamines) can induce euphoria. The effects of neurotransmitters on personality traits have generated much interest and controversy about whether personality traits are inborn or acquired.

Electrophysiology. Changes in electrical conductance on the electroencephalogram (EEG) occur in some patients with personality disorders, most commonly antisocial and borderline types; these changes appear as slow-wave activity on EEGs.

Psychoanalytic Factors

Sigmund Freud suggested that personality traits are related to a fixation at one psychosexual stage of development. For example, those with an oral character are passive and dependent because they are fixated at the oral stage, when the dependence on others for food is prominent. Those with an anal character are stubborn, parsimonious, and highly conscientious because of struggles over toilet training during the anal period.

Wilhelm Reich subsequently coined the term character armor to describe persons’ characteristic defensive styles for protecting themselves from internal impulses and from interpersonal anxiety in significant relationships. Reich’s theory has had a broad influence on contemporary concepts of personality and personality disorders. For example, each human being’s unique stamp of personality is considered largely determined by his or her characteristic defense mechanisms. Each personality disorder has a cluster of defenses that help psychodynamic clinicians recognize the type of character pathology present. Persons with paranoid personality disorder, for instance, use projection, whereas schizoid personality disorder is associated with withdrawal.

When defenses work effectively, persons with personality disorders master feelings of anxiety, depression, anger, shame, guilt, and other affects. Their behavior is ego syntonic; that is, it creates no distress for them even though it may adversely affect others. They may also be reluctant to engage in a treatment process; because their defenses are important in controlling unpleasant affects, they are not interested in surrendering them.

In addition to characteristic defenses in personality disorders, another central feature is internal object relations. During development, particular patterns of the self in relation to others are internalized. Through introjection, children internalize a parent or another significant person as an internal presence that continues to feel like an object rather than a self. Through identification, children internalize parents and others in such a way that the traits of the external object are incorporated into the self and the child “owns” the traits. These internal self-representations and object representations are crucial in developing the personality and, through externalization and projective identification, are played out in interpersonal scenarios in which others are coerced into playing a role in the person’s internal life. Hence, persons with personality disorders are also identified by particular patterns of interpersonal relatedness that stem from these internal object relations patterns.

Defense Mechanisms. To help those with personality disorders, psychiatrists must appreciate patients’ underlying defenses, the unconscious mental processes that the ego uses to resolve conflicts among the four lodestars of the inner life: instinct (wish or need), reality, important persons, and conscience. When defenses are most effective, especially in those with personality disorders, they can abolish anxiety and depression at the conscious level. Thus, abandoning a defense increases conscious awareness of anxiety and depression—a major reason that those with personality disorders are reluctant to alter their behavior.

Although patients with personality disorders may be characterized by their most dominant or rigid mechanism, each patient uses several defenses. Therefore, the management of defense mechanisms used by patients with personality disorders is discussed here as a general topic and not as an aspect of the specific disorders. Many formulations presented here in the language of psychoanalytic psychiatry can be translated into principles consistent with cognitive and behavioral approaches.

FANTASY. Many persons who are often labeled schizoid—those who are eccentric, lonely, or frightened—seek solace and satisfaction within themselves by creating imaginary lives, especially imaginary friends. In their extensive dependence on fantasy, these persons often seem to be strikingly aloof. Therapists must understand that the unsociableness of these patients rests on a fear of intimacy. Rather than criticizing them or feeling rebuffed by their rejection, therapists should maintain a quiet, reassuring, and considerate interest without insisting on reciprocal responses. Recognition of patients’ fear of closeness and respect for their eccentric ways are both therapeutic and useful.

DISSOCIATION. Dissociation or denial is a Pollyanna-like replacement of unpleasant affects with pleasant ones. Persons who frequently dissociate are often seen as dramatizing and emotionally shallow; they may be labeled histrionic personalities. They behave like anxious adolescents who, to erase anxiety, carelessly expose themselves to exciting dangers. Accepting such patients as exuberant and seductive is to overlook their anxiety, but confronting them with their vulnerabilities and defects makes them still more defensive. Because these patients seek appreciation of their courage and attractiveness, therapists should not behave with inordinate reserve. While remaining calm and firm, clinicians should realize that these patients are often inadvertent liars, but they benefit from ventilating their own anxieties and may in the process “remember” what they “forgot.” Often therapists deal best with dissociation and denial by using displacement. Thus, clinicians may talk with patients about an issue of denial in an unthreatening circumstance. Empathizing with the denied affect without directly confronting patients with the facts may allow them to raise the original topic themselves.

ISOLATION. Isolation is characteristic of controlled, orderly persons who are often labeled obsessive-compulsive personalities. Unlike those with histrionic personality, persons with obsessive-compulsive personality remember the truth in fine detail but without affect. In a crisis, patients may show intensified self-restraint, overly formal social behavior, and obstinacy. Patients’ quests for control may annoy clinicians or make them anxious. Often, such patients respond well to precise, systematic, and rational explanations and value efficiency, cleanliness, and punctuality as much as they do clinicians’ effective responsiveness. Whenever possible, therapists should allow such patients to control their own care and should not engage in a battle of wills.

PROJECTION. In projection, patients attribute their own unacknowledged feelings to others. Patients’ excessive faultfinding and sensitivity to criticism may appear to therapists as prejudiced, hypervigilant injustice collecting but should not be met by defensiveness and argument. Instead, clinicians should frankly acknowledge even minor mistakes on their part and should discuss the possibility of future difficulties. Strict honesty; concern for patients’ rights; and maintaining the same formal, concerned distance as used with patients who use fantasy defenses are all helpful. Confrontation guarantees a lasting enemy and early termination of the interview. Therapists need not agree with patients’ injustice collecting, but they should ask whether both can agree to disagree.

The technique of counterprojection is especially helpful. Clinicians acknowledge and give paranoid patients full credit for their feelings and perceptions; they neither dispute patients’ complaints nor reinforce them but agree that the world described by patients is conceivable. Interviewers can then talk about real motives and feelings, misattributed to someone else, and begin to cement an alliance with patients.

SPLITTING. In splitting, persons toward whom patients’ feelings are, or have been, ambivalent are divided into good and bad. For example, in an inpatient setting, a patient may idealize some staff members and uniformly disparage others. This defense behavior can be highly disruptive on a hospital ward and can ultimately provoke the staff to turn against the patient. When staff members anticipate the process, discuss it at staff meetings, and gently confront the patient with the fact that no one is all good or all bad, the phenomenon of splitting can be dealt with effectively.

PASSIVE AGGRESSION. Persons with passive-aggressive defense turn their anger against themselves. In psychoanalytic terms, this phenomenon is called masochism and includes failure, procrastination, silly or provocative behavior, self-demeaning clowning, and frankly self-destructive acts. The hostility in such behavior is never entirely concealed. Indeed, in a mechanism such as wrist cutting, others feel as much anger as if they themselves had been assaulted and view the patient as a sadist, not a masochist. Therapists can best deal with passive aggression by helping patients to ventilate their anger.

ACTING OUT. In acting out, patients directly express unconscious wishes or conflicts through action to avoid being conscious of either the accompanying idea or the affect. Tantrums, apparently motiveless assaults, child abuse, and pleasureless promiscuity are common examples. Because the behavior occurs outside reflective awareness, acting out often appears to observers to be unaccompanied by guilt, but when acting out is impossible, the conflict behind the defense may be accessible. The clinician faced with acting out, either aggressive or sexual, in an interview situation must recognize that the patient has lost control, that anything the interviewer says will probably be misheard, and that getting the patient’s attention is of paramount importance. Depending on the circumstances, a clinician’s response may be, “How can I help you if you keep screaming?” Or, if the patient’s loss of control seems to be escalating, say, “If you continue screaming, I’ll leave.” An interviewer who feels genuinely frightened of the patient can simply leave and, if necessary, ask for help from ward attendants or the police.

PROJECTIVE IDENTIFICATION. The defense mechanism of projective identification appears mainly in borderline personality disorder and consists of three steps. First, an aspect of the self is projected onto someone else. The projector then tries to coerce the other person into identifying with what has been projected. Finally, the recipient of the projection and the projector feel a sense of oneness or union.

PARANOID PERSONALITY DISORDER

Persons with paranoid personality disorder are characterized by long-standing suspiciousness and mistrust of persons in general. They refuse responsibility for their own feelings and assign responsibility to others. They are often hostile, irritable, and angry. Bigots, injustice collectors, pathologically jealous spouses, and litigious cranks often have paranoid personality disorder.

Epidemiology

Data suggest that the prevalence of paranoid personality disorder is 2 to 4 percent of the general population. Those with the disorder rarely seek treatment themselves; when referred to treatment by a spouse or an employer, they can often pull themselves together and appear undistressed. Relatives of patients with schizophrenia show a higher incidence of paranoid personality disorder than control participants. Some evidence suggests a more specific familial relationship with delusional disorder, persecutory type. The disorder is more commonly diagnosed in men than in women in clinical samples. The prevalence among persons who are homosexual is no higher than usual, as was once thought, but it is believed to be higher among minority groups, immigrants, and persons who are deaf than it is in the general population.

Diagnosis

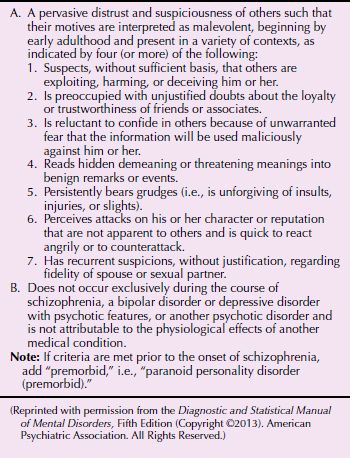

On psychiatric examination, patients with paranoid personality disorder may be formal in manner and act baffled about having to seek psychiatric help. Muscular tension, an inability to relax, and a need to scan the environment for clues may be evident, and the patient’s manner is often humorless and serious. Although some premises of their arguments may be false, their speech is goal directed and logical. Their thought content shows evidence of projection, prejudice, and occasional ideas of reference. The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria are listed in Table 22-1.

Table 22-1

Table 22-1

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Paranoid Personality Disorder

Clinical Features

The hallmarks of paranoid personality disorder are excessive suspiciousness and distrust of others expressed as a pervasive tendency to interpret actions of others as deliberately demeaning, malevolent, threatening, exploiting, or deceiving. This tendency begins by early adulthood and appears in a variety of contexts. Almost invariably, those with the disorder expect to be exploited or harmed by others in some way. They frequently dispute, without any justification, friends’ or associates’ loyalty or trustworthiness. Such persons are often pathologically jealous and, for no reason, question the fidelity of their spouses or sexual partners. Persons with this disorder externalize their own emotions and use the defense of projection; they attribute to others the impulses and thoughts that they cannot accept in themselves. Ideas of reference and logically defended illusions are common.

Persons with paranoid personality disorder are affectively restricted and appear to be unemotional. They pride themselves on being rational and objective, but such is not the case. They lack warmth and are impressed with, and pay close attention to, power and rank. They express disdain for those they see as weak, sickly, impaired, or in some way defective. In social situations, persons with paranoid personality disorder may appear business-like and efficient, but they often generate fear or conflict in others.

Differential Diagnosis

Paranoid personality disorder can usually be differentiated from delusional disorder by the absence of fixed delusions. Unlike persons with paranoid schizophrenia, those with personality disorders have no hallucinations or formal thought disorder. Paranoid personality disorder can be distinguished from borderline personality disorder because patients who are paranoid are rarely capable of overly involved, tumultuous relationships with others. Patients with paranoia lack the long history of antisocial behavior of persons with antisocial character. Persons with schizoid personality disorder are withdrawn and aloof and do not have paranoid ideation.

Course and Prognosis

No adequate, systematic long-term studies of paranoid personality disorder have been conducted. In some, paranoid personality disorder is lifelong; in others, it is a harbinger of schizophrenia. In still others, paranoid traits give way to reaction formation, appropriate concern with morality, and altruistic concerns as they mature or as stress diminishes. In general, however, those with paranoid personality disorder have lifelong problems working and living with others. Occupational and marital problems are common.

Treatment

Psychotherapy. Psychotherapy is the treatment of choice for those with paranoid personality disorder. Therapists should be straightforward in all their dealings with these patients. If a therapist is accused of inconsistency or a fault, such as lateness for an appointment, honesty and an apology are preferable to a defensive explanation. Therapists must remember that trust and toleration of intimacy are troubled areas for patients with this disorder. Individual psychotherapy thus requires a professional and not overly warm style from therapists. Clinicians’ overzealous use of interpretation—especially interpretation about deep feelings of dependence, sexual concerns, and wishes for intimacy—increases patients’ mistrust significantly. Patients who are paranoid usually do not do well in group psychotherapy, although it can be useful for improving social skills and diminishing suspiciousness through role playing. Many cannot tolerate the intrusiveness of behavior therapy, also used for social skills training.

At times, patients with paranoid personality disorder behave so threateningly that therapists must control or set limits on their actions. Delusional accusations must be dealt with realistically but gently and without humiliating patients. Patients who are paranoid are profoundly frightened when they feel that those trying to help them are weak and helpless; therefore, therapists should never offer to take control unless they are willing and able to do so.

Pharmacotherapy. Pharmacotherapy is useful in dealing with agitation and anxiety. In most cases, an antianxiety agent such as diazepam (Valium) suffices. It may be necessary, however, to use an antipsychotic such as haloperidol (Haldol) in small dosages and for brief periods to manage severe agitation or quasi-delusional thinking. The antipsychotic drug pimozide (Orap) has successfully reduced paranoid ideation in some patients.

SCHIZOID PERSONALITY DISORDER

Schizoid personality disorder is characterized by a lifelong pattern of social withdrawal. Persons with schizoid personality disorder are often seen by others as eccentric, isolated, or lonely. Their discomfort with human interaction; their introversion; and their bland, constricted affect are noteworthy.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of schizoid personality disorder is not clearly established, but the disorder may affect 5 percent of the general population. The sex ratio of the disorder is unknown; some studies report a 2-to-1 male-to-female ratio. Persons with the disorder tend to gravitate toward solitary jobs that involve little or no contact with others. Many prefer night work to day work so that they need not deal with many persons.

Diagnosis

On an initial psychiatric examination, patients with schizoid personality disorder may appear ill at ease. They rarely tolerate eye contact, and interviewers may surmise that such patients are eager for the interview to end. Their affect may be constricted, aloof, or inappropriately serious, but underneath the aloofness, sensitive clinicians can recognize fear. These patients find it difficult to be lighthearted: Their efforts at humor may seem adolescent and off the mark. Their speech is goal directed, but they are likely to give short answers to questions and to avoid spontaneous conversation. They may occasionally use unusual figures of speech, such as an odd metaphor, and may be fascinated with inanimate objects or metaphysical constructs. Their mental content may reveal an unwarranted sense of intimacy with persons they do not know well or whom they have not seen for a long time. Their sensorium is intact, their memory functions well, and their proverb interpretations are abstract. The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria are listed in Table 22-2.

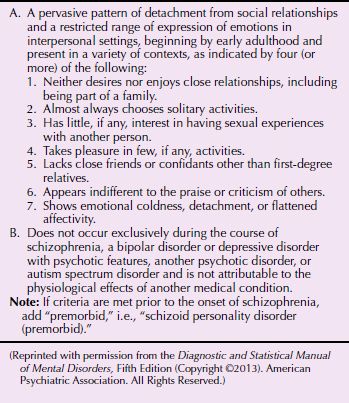

Table 22-2

Table 22-2

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Schizoid Personality Disorder

Clinical Features

Persons with schizoid personality disorder seem to be cold and aloof; they display a remote reserve and show no involvement with everyday events and the concerns of others. They appear quiet, distant, seclusive, and unsociable. They may pursue their own lives with remarkably little need or longing for emotional ties, and they are the last to be aware of changes in popular fashion.

The life histories of such persons reflect solitary interests and success at noncompetitive, lonely jobs that others find difficult to tolerate. Their sexual lives may exist exclusively in fantasy, and they may postpone mature sexuality indefinitely. Men may not marry because they are unable to achieve intimacy; women may passively agree to marry an aggressive man who wants the marriage. Persons with schizoid personality disorder usually reveal a lifelong inability to express anger directly. They can invest enormous affective energy in nonhuman interests, such as mathematics and astronomy, and they may be very attached to animals. Dietary and health fads, philosophical movements, and social improvement schemes, especially those that require no personal involvement, often engross them.

Although persons with schizoid personality disorder appear self-absorbed and lost in daydreams, they have a normal capacity to recognize reality. Because aggressive acts are rarely included in their repertoire of usual responses, most threats, real or imagined, are dealt with by fantasized omnipotence or resignation. They are often seen as aloof, yet such persons can sometimes conceive, develop, and give to the world genuinely original, creative ideas.

Differential Diagnosis

Schizoid personality disorder is distinguished from schizophrenia, delusional disorder, and affective disorder with psychotic features based on periods with positive psychotic symptoms, such as delusions and hallucinations in the latter. Although patients with paranoid personality disorder share many traits with those with schizoid personality disorder, the former exhibit more social engagement, a history of aggressive verbal behavior, and a greater tendency to project their feelings onto others. If just as emotionally constricted, patients with obsessive-compulsive and avoidant personality disorders experience loneliness as dysphoric, possess a richer history of past object relations, and do not engage as much in autistic reverie. Theoretically, the chief distinction between a patient with schizotypal personality disorder and one with schizoid personality disorder is that the patient who is schizotypal is more similar to a patient with schizophrenia in oddities of perception, thought, behavior, and communication. Patients with avoidant personality disorder are isolated but strongly wish to participate in activities, a characteristic absent in those with schizoid personality disorder. Schizoid personality disorder is distinguished from autistic disorder and Asperger’s syndrome by more severely impaired social interactions and stereotypical behaviors and interests than in those two disorders.

Course and Prognosis

The onset of schizoid personality disorder usually occurs in early childhood or adolescence. As with all personality disorders, schizoid personality disorder is long lasting but not necessarily lifelong. The proportion of patients who incur schizophrenia is unknown.

Treatment

Psychotherapy. The treatment of patients with schizoid personality disorder is similar to that of those with paranoid personality disorder. Patients who are schizoid tend toward introspection; however, these tendencies are consistent with psychotherapists’ expectations, and such patients may become devoted, if distant, patients. As trust develops, patients who are schizoid may, with great trepidation, reveal a plethora of fantasies, imaginary friends, and fears of unbearable dependence—even of merging with the therapist.

In group therapy settings, patients with schizoid personality disorder may be silent for long periods; nonetheless, they do become involved. The patients should be protected against aggressive attack by group members for their proclivity to be silent. With time, the group members become important to patients who are schizoid and may provide the only social contact in their otherwise isolated existence.

Pharmacotherapy. Pharmacotherapy with small dosages of antipsychotics, antidepressants, and psychostimulants has benefitted some patients. Serotonergic agents may make patients less sensitive to rejection. Benzodiazepines may help diminish interpersonal anxiety.

SCHIZOTYPAL PERSONALITY DISORDER

Persons with schizotypal personality disorder are strikingly odd or strange, even to laypersons. Magical thinking, peculiar notions, ideas of reference, illusions, and derealization are part of a schizotypal person’s everyday world.

Epidemiology

Schizotypal personality disorder occurs in about 3 percent of the population. The sex ratio is unknown; however, it is frequently diagnosed in females with fragile X syndrome. DSM-5 suggests the disorder may be slightly more common in males. A greater association of cases exists among the biological relatives of patients with schizophrenia than among control participants and a higher incidence among monozygotic twins than among dizygotic twins (33 percent vs. 4 percent in one study).

Etiology

Adoption, family, and twin studies demonstrate an increased prevalence of schizotypal features in the families of schizophrenic patients, especially when schizotypal features were not associated with comorbid affective symptoms.

Diagnosis

Schizotypal personality disorder is diagnosed on the basis of the patients’ peculiarities of thinking, behavior, and appearance. Taking a history may be difficult because of the patients’ unusual way of communicating. The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for schizotypal personality disorder are given in Table 22-3.

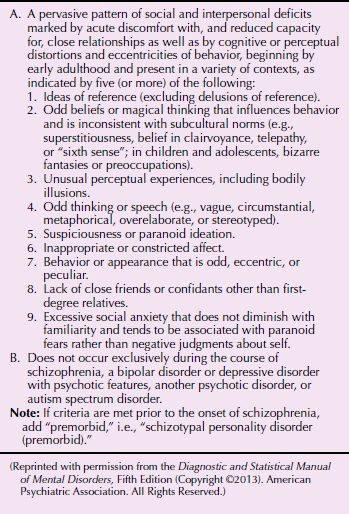

Table 22-3

Table 22-3

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Schizotypal Personality Disorder

Clinical Features

Patients with schizotypal personality disorder exhibit disturbed thinking and communicating. Although frank thought disorder is absent, their speech may be distinctive or peculiar, may have meaning only to them, and often needs interpretation. As with patients with schizophrenia, those with schizotypal personality disorder may not know their own feelings and yet are exquisitely sensitive to, and aware of, the feelings of others, especially negative affects such as anger. These patients may be superstitious or claim powers of clairvoyance and may believe that they have other special powers of thought and insight. Their inner world may be filled with vivid imaginary relationships and child-like fears and fantasies. They may admit to perceptual illusions or macropsia and confess that other persons seem wooden and all the same.

Because persons with schizotypal personality disorder have poor interpersonal relationships and may act inappropriately, they are isolated and have few, if any, friends. Patients may show features of borderline personality disorder, and indeed, both diagnoses can be made. Under stress, patients with schizotypal personality disorder may decompensate and have psychotic symptoms, but these are usually brief. Patients with severe cases of the disorder may exhibit anhedonia and severe depression.

Differential Diagnosis

Theoretically, persons with schizotypal personality disorder can be distinguished from those with schizoid and avoidant personality disorders by the presence of oddities in their behavior, thinking, perception, and communication and perhaps by a clear family history of schizophrenia. Patients with schizotypal personality disorder can be distinguished from those with schizophrenia by their absence of psychosis. If psychotic symptoms do appear, they are brief and fragmentary. Some patients meet the criteria for both schizotypal personality disorder and borderline personality disorder. Patients with paranoid personality disorder are characterized by suspiciousness but lack the odd behavior of patients with schizotypal personality disorder.

Course and Prognosis

According to current clinical thinking, the schizotype is the premorbid personality of the patient with schizophrenia. Some, however, maintain a stable schizotypal personality throughout their lives and marry and work, despite their oddities. A long-term study by Thomas McGlashan reported that 10 percent of those with schizotypal personality disorder eventually committed suicide.

Treatment

Psychotherapy. The principles of treatment of schizotypal personality disorder do not differ from those of schizoid personality disorder, but clinicians must deal sensitively with the former. These patients have peculiar patterns of thinking, and some are involved in cults, strange religious practices, and the occult. Therapists must not ridicule such activities or be judgmental about these beliefs or activities.

Pharmacotherapy. Antipsychotic medication may be useful in dealing with ideas of reference, illusions, and other symptoms of the disorder and can be used in conjunction with psychotherapy. Antidepressants are useful when a depressive component of the personality is present.

ANTISOCIAL PERSONALITY DISORDER

Antisocial personality disorder is an inability to conform to the social norms that ordinarily govern many aspects of a person’s adolescent and adult behavior. Although characterized by continual antisocial or criminal acts, the disorder is not synonymous with criminality.

Epidemiology

The 12-month prevalence rates of antisocial personality disorder are between 0.2 and 3 percent according to DSM-5. It is more common in poor urban areas and among mobile residents of these areas. The highest prevalence of antisocial personality disorder is found among the most severe samples of men with alcohol use disorder (over 70 percent) and in prison populations, where the prevalence may be as high as 75 percent. It is much more common in males than in females. Boys with the disorder come from larger families than girls with the disorder. The onset of the disorder is before the age of 15 years. Girls usually have symptoms before puberty and boys even earlier. A familial pattern is present; the disorder is five times more common among first-degree relatives of men with the disorder than among control participants.

Diagnosis

Patients with antisocial personality disorder can fool even the most experienced clinicians. In an interview, patients can appear composed and credible, but beneath the veneer (or, to use Hervey Cleckley’s term, the mask of sanity

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree