Drugs used for obesity treatment can, in theory, target and decrease food intake or energy absorption, or increase physical activity or basal metabolism/energy expenditure, but drugs currently approved for weight-loss treatment target only a few of these. Many drugs that affect weight are not suitable for use in obesity therapy because they have other effects that are undesirable. Thus, the history of pharmacological treatments includes several drugs no longer used because the risks outweighed the benefits. Examples include phenylpropanolamine and fenfluramine (1) (see Box 18-1).

Box 18-1

Despite the success of combining fenfluramine and phentermine as a weight loss agent, fenfluramine was removed from the market because of unanticipated side effects. To quote the Food and Drug Administration:

“Fenfluramine and dexfenfluramine are appetite suppressants that were in widespread use in the United States. On July 8, 1997, 24 cases of valvular heart disease in women who had been treated with fenfluramine and phentermine were publicly reported. Although valvular lesions were observed on both sides of the heart, a leftsided valve was affected in all cases. The histopathologic features were similar to those observed in carcinoid-induced valvular disease, a serotonin-related syndrome.

Based on these data, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a public health advisory on July 8, followed by letters from FDA to 700,000 U.S. health-care practitioners and institutions requesting information about any additional similar patients. Subsequently, reports of fenfluramine- or dexfenfluramine-associated valvulopathy increased …

Because symptoms frequently occur relatively late during the course of valvular incompetence, the prevalence of valve lesions was assessed for patients who were exposed to these drugs but who had no obvious history of cardiac disease or cardiac symptoms. In early September, FDA received echocardiographic reports from five independent, unpublished echocardiographic prevalence surveys of patients who had received dexfenfluramine or fenfluramine alone or in combination with phentermine …

Based on data from the five prevalence surveys, FDA requested the voluntary withdrawal of fenfluramine and dexfenfluramine from the U.S. market; on September 15, the manufacturers and FDA announced the withdrawal of the drugs.”

From: www.fda.gov/cder/news/mmwr.pdf (accessed November 2, 2008).

Principles for Using Obesity Medications

The rationale for the use of medications in the management of obesity is that they can help more patients achieve clinically meaningful weight loss when those patients are making lifestyle changes to reduce weight. Obesity medications used alone have only small effects on weight; they are most helpful for supporting behavioral approaches to weight loss as adjuncts to lifestyle changes. Those currently available have been shown to produce greater weight loss than lifestyle changes alone, at least doubling the chances of achieving 5–10% loss, enough for a clinically significant improvement in the health profile. However, because medications have associated risks and side-effects and do not result in large weight losses, they generally should not be used for strictly cosmetic weight loss.

In using medications for weight management, health improvement should be the goal of therapy and the basis of patient selection. In assessing use of medications, the health risk from overweight should be weighed against the risks and side-effects of the medications themselves. Medications approved by the Food and Drug Administration for long-term use for weight loss are appropriate for subjects with a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or more, or 27 kg/m2 or more in those with a comorbid condition such as hypertension, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia, according to current prescription guidelines. Inclusion of the metabolic syndrome as a comorbid condition is also worth considering. If an individual with a BMI > 27 meets the National Cholesterol Education Program, Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATPIII) criteria for metabolic syndrome (see Box 18-2), then the pharmaceutical treatment of obesity may be indicated. We support the use of a metabolic syndrome diagnosis for determining eligibility for pharmacotherapy, because this diagnosis identifies individuals who have somewhat lower levels of lipids, blood pressure, and fasting glucose than the values traditionally used to identify risk, yet for whom weight loss is likely to reduce the risk of development of diabetes or cardiovascular disease (1).

Box 18-2 Metabolic syndrome: clinical identification

Diagnostic Values: Diagnosis is made when three of five of the following characteristics are present

| • Abdominal Obesity | Waist Circumference |

| Men | >40 in (102 cm) |

| Women | >35 in (88 cm) |

| • Blood Pressure | ≥130/≥85 mmHg |

| • Fasting Glucose | ≥100 mg/dL |

| • Triglycerides | ≥150 mg/dL |

| • HDL | |

| Men | <40 mg/dL |

| Women | <50 mg/dL |

Measurement of waist circumference is also desirable. The NCEP ATPIII definition of metabolic syndrome includes a waist circumference of >102 cm (40 in) for a man and >88 cm (35 in) for a woman, but cutoffs distinguished by ethnicity are helpful (see Box 18-2). Metabolic syndrome now has a widely accepted diagnostic framework. The five criteria are the same except that waist circumference has country- or region-specific criteria (2).

Selecting Patients Suitable for Using Medications for Weight Management

Once it is established that the patient is an appropriate candidate for medically supervised weight loss, an assessment of the patient’s motivation must be made. Weight loss is hard work and patients must be highly motivated to be successful. A weight-loss goal should be set collaboratively, with consideration of the patient’s circumstances, history of weight loss, and motivation. Most patients have an unrealistic view of how much weight they can lose. For many, a weight loss of <15% would be viewed as a failure. In contrast, weight loss using monotherapy with the currently available drugs is usually not greater than 10%, even when a lifestyle intervention is included. It is thus important for physician and patient alike to set a weight-loss goal for initial therapy that is not more than 10% of body weight, with a weight loss of less than 5% suggesting that an alternative strategy is needed. However, even modest weight loss (5–10%) can improve comorbidities and reduce associated health risks. Effective pharmacotherapy depends on linking the associated behavioral approach to the drug’s mechanism of action. Therefore, it is helpful if the patient understands the drug’s mechanism of action, in addition to its potential side-effects.

In general, about a quarter of persons who are prescribed an obesity medication will not have an acceptable response (of more than 5% weight loss). If weight loss is insufficient, the medication should not be continued. Generally, a loss of 1.8 kg (4 lb) in the first four weeks is indicative that a weight loss of at least 5% will be observed after six months of drug therapy. For example, of patients who lost 2 kg (4.4 lb) in the first four weeks of treatment with sibutramine, 60% achieved a weight loss of more than 5%, while less than 10% of those who did not lose 2 kg (4.4 lb) in four weeks achieved this level of weight loss (3). The reality is that obesity medications do not cure obesity. As with most diets of any kind, current medications typically result in a weight loss that plateaus after about six months of treatment, with weight regain occurring if the medication is stopped.

Only a fraction of patients eligible for using obesity medications to reduce or control body weight have such medications prescribed. This may be partly due to lack of insurance reimbursements for drug treatment, the limited amount of weight lost, the lack of recognition of its importance, and the reluctance of some physicians to work in this difficult and stigmatized area.

Benefits of Modest Weight Loss

The health benefits of modest weight loss need to be recognized by both the practitioner and the patient. Blood pressure, blood lipid levels, and control of blood glucose may all be improved with as little as 5–10% weight loss, as can comorbid conditions such as sleep apnea and arthritis. For example, a weight loss of 7% in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance was associated with a 58% reduction in risk for development of type 2 diabetes over 2–5 years in the Diabetes Prevention Program (4).

Drugs Used

Few medications are approved by the FDA for prescription for weight loss. Nevertheless, the American College of Physicians (5) recommended six medications, only three of which (orlistat for long-term use, phentermine and diethylpropion for short-term use) are currently approved by the FDA for treatment of overweight patients. The other three, sibutramine, fluoxetine and bupropion, as well as a seventh, sertraline (also used to treat obesity), are not FDA-approved for weight loss and should not be used primarily for this purpose, although fluoxetine and bupropion may be useful in management of depression in overweight patients, and bupropion may be helpful in reducing or preventing weight gain associated with smoking cessation efforts.

Drugs approved by the FDA for long-term treatment of overweight

Orlistat

Mechanism of Actions

In pharmacological studies, orlistat was shown to be a potent selective inhibitor of pancreatic lipase, inhibiting the breakdown and absorption of dietary fat. The drug has a dose-dependent effect on fecal fat loss, increasing it to approximately 30% on a diet that has 30% of its energy as fat. Orlistat has little effect in subjects eating a low-fat diet, as might be anticipated from its mechanism of action (see 1).

Weight-Loss Trials

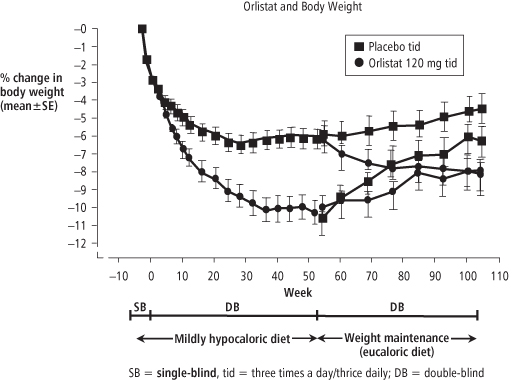

Several two-year and one four-year trial of orlistat in hundreds of subjects have been reported (1). They have used a variety of designs to study what we will call “low-dose” (60 mg, three times per day) and “high-dose” (120 mg, three times per day) regimens. The results of a two-year cross-over trial of orlistat and placebo are shown in Figure 18-3 (15). In the first year, patients received a diet calculated to be 500 kcal per day less than the patient’s requirements. During the second year, the diet was calculated to maintain weight. By the end of year 1, the placebo-treated patients lost 6.1% of their initial body weight and the high-dose drug-treated group lost 10.2%. The patients were randomized again at the end of year 1. Those switched from orlistat to placebo gained weight while those switched from placebo to orlistat lost weight, ending at a weight that was essentially identical to the loss in patients treated with orlistat for the full two years.

A four-year double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial with orlistat has also been reported (16). A total of 3,305 overweight patients, 21% of whom had impaired glucose tolerance, were included. Lifestyle changes and a reduced-calorie diet were prescribed to all groups. The lowest body weight was achieved during the first year, more than 11% (10.6 kg) below baseline in the high-dose orlistat-treated group and 6% (6.2 kg) below baseline in the placebo-treated group. Over the remaining three years of the trial, there was a small regain in weight, such that by the end of four years, the orlistat-treated patients were 6.9% (5.8 kg) below baseline, compared with 4.1% (3.0 kg) below for those receiving placebo. The trial also showed a 37% reduction in the development of diabetes, essentially all of which benefit occurred in those with impaired glucose tolerance at enrollment into the trial. In all 52% of the orlistat-treated subjects and 34% of the placebo-treated subjects completed four years of treatment.

An over-the-counter version of orlistat is approved by the FDA. It is available in 60 mg doses to be used three times per day for up to six months along with the weight-loss program provided when the product is purchased at a pharmacy, drug store, or supermarket. Its manufacturer showed that moderately overweight individuals (BMI 25–28 kg/m2) who use over-the-counter orlistat three times per day could lose 50% more than the weight loss observed with placebo-treated patients when all of them were eating the same diet.

Weight Maintenance After Weight Loss

Weight maintenance with orlistat was evaluated in a one-year study (see 1). Patients were enrolled if they had lost more than 8% of their body weight over six months while eating a 1,000 kcal/day (4,180 kJ/day) diet. The 729 patients were randomized to receive placebo or orlistat at 30 mg, 60 mg, or 120 mg three times per day. At the end of 12 months, the placebo-treated patients had regained 56% of their prior weight loss, compared with 32.4% in the group treated with the highest dose of orlistat. Regain of weight on the two lower doses of orlistat was not different from placebo.

Studies of Patients with Comorbidities (Hypertension, Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome)

Patients with type 2 diabetes, treated for one year with high-dose orlistat, lost more weight and showed a significantly greater decrease in hemoglobin A1C levels than did those receiving a placebo (17–19). Investigators have also pooled data on 675 subjects from three two-year studies with orlistat in which glucose tolerance tests were available (20). Of the patients taking orlistat, 6.6% converted from a normal to an impaired glucose tolerance, significantly less than the 10.8% conversion in the placebo-treated group. None of the orlistat-treated patients who originally had normal glucose tolerance developed diabetes, compared with 1.2% in the placebo-treated group. Of those who initially had normal glucose tolerance, 7.6% in the placebo group but significantly fewer, only 3%, in the orlistat-treated group developed diabetes.

Studies in Children and Adolescents

A multi-center trial tested the effect of orlistat in 539 obese adolescents with an average age of 13.5 years. (21). Subjects were randomized to placebo or high-dose orlistat and a mildly hypocaloric diet containing 30% fat. By the end of the study, BMI had decreased 0.6 kg/m2 and weight increased by 0.5 kg in the orlistat-treated group (increase in weight with decrease in BMI is possible as children mature); the respective changes were +0.3 kg/m2 BMI and +3.1 kg weight in the placebo group. The differences were due to differences in body fat. The side-effects were gastrointestinal, as expected from the mode of action of orlistat.

Safety

Orlistat is not absorbed from the GI tract to any significant degree, and its side-effects are thus related to the blockade of triglyceride digestion in the intestine (see 1). GI symptoms are common initially and can include borborygmi, flatulence, anal leakage, and fecal incontinence. Steatorrheal diarrhea can be expected if the diet is not low in fat, but episodes are few and generally not severe; they subside as patients learn to use the drug. The quality of life in patients treated with orlistat may improve despite concerns about GI symptoms. Orlistat can cause small but significant decreases in levels of fat-soluble vitamins. Levels usually remain within the normal range, but a few patients may need vitamin supplementation. Because it is impossible to tell which patients will need vitamins, routine use of a multivitamin supplement is appropriate, with instructions to take it before bedtime. On the plus side, orlistat lowers LDL cholesterol more than expected from any associated weight loss. Orlistat does not seem to affect the absorption of other drugs, except cyclosporin.

Drugs Approved by the FDA for Short-Term Treatment of Overweight

Phentermine and Diethylpropion

Phentermine and diethylpropion are classified by the US Drug Enforcement Agency as schedule IV drugs; benzphetamine and phendimetrazine are schedule III drugs. This regulatory classification indicates the government’s belief that these drugs have the potential for abuse, although this potential appears to be very low. Phentermine and diethylpropion are approved for only a “few weeks,” which usually is interpreted as up to 12 weeks in a year.

Most of the data on these drugs come from short-term trials. One of the longest of these clinical trials lasted 36 weeks and compared placebo treatment with continuous or intermittent phentermine (23). Both continuous and intermittent phentermine therapy produced significantly more weight loss than placebo. Patients treated intermittently had a slowing of weight loss during the periods when the drug was withdrawn and lost weight more rapidly when the drug was started again.

Box 18-3 Case study of sibutramine, a drug once approved by the FDA for long-term treatment of overweight, but with approval eventually revoked

Sibutramine

Sibutramine is an interesting example of a weight loss drug that was studied for a long time, showed promise for treatment of obesity, but which was eventually removed from the market. It illustrates the difficulties encountered in development of drugs for long-term use in the treatment of obesity.

Mechanism of Actions

Sibutramine is a highly selective inhibitor of the reuptake at nerve endings of the neurotransmitters norepinephrine and serotonin, and, to a lesser degree, dopamine. It was marketed in the US as Meridia and as Reductil elsewhere. In humans, sibutramine acts acutely, mostly by reducing food intake. In animals, it also increases energy expenditure, increasing resting metabolic rate, but the data on this effect in humans are conflicting. Because sibutramine promotes satiety, weight loss was greatest when it was used with a controlled, sensible diet, such as one with three portion-controlled meals and two snacks.

Food Intake

The effect of sibutramine on food intake can be substantial. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, two-week trial, a 30 mg/day dose reduced food intake by 23% on day 7 and 26% on day 14, relative to placebo. A 10 mg dose also significantly reduced food intake at 14 days with fewer side-effects (1).

Weight Loss

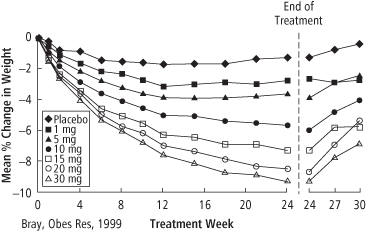

Sibutramine was available in 5, 10, and 15 mg doses; a single dose of 10 mg/day was the recommended starting level, with titration up or down depending on response. Sibutramine was demonstrated to have a dose-response weight-loss effect. After six months of treatment with doses ranging from 1 to 30 mg/day in a double-blind study, 67% of patients showed at least a 5% weight loss with 35% losing 10% or more. Weight regain occurred when sibutramine was discontinued (see Figure 18-2) (2). In another trial, sibutramine (10 mg/day) produced additional weight loss in patients who initially lost weight by consuming a very-low-calorie diet, whereas those randomized to the placebo regained weight (6). The studies described below have mostly used dosages of 10–20 mg/day, although some used a gradual increase from a lower to a higher dose.

Figure 18-2 Dose-response Effect of Sibutramine in a Multicenter Study

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree