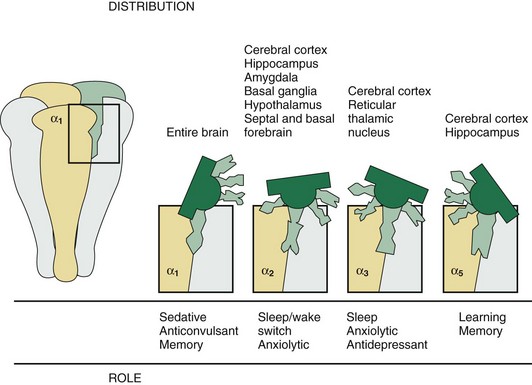

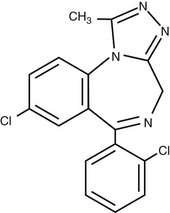

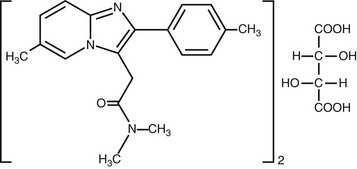

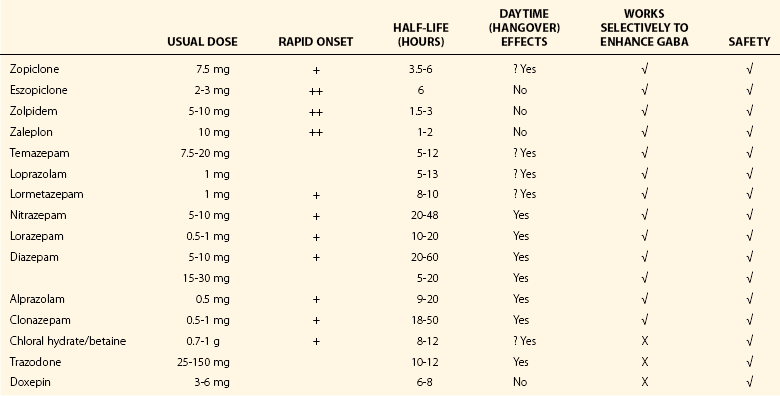

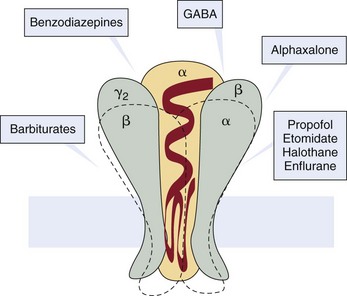

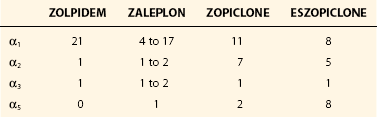

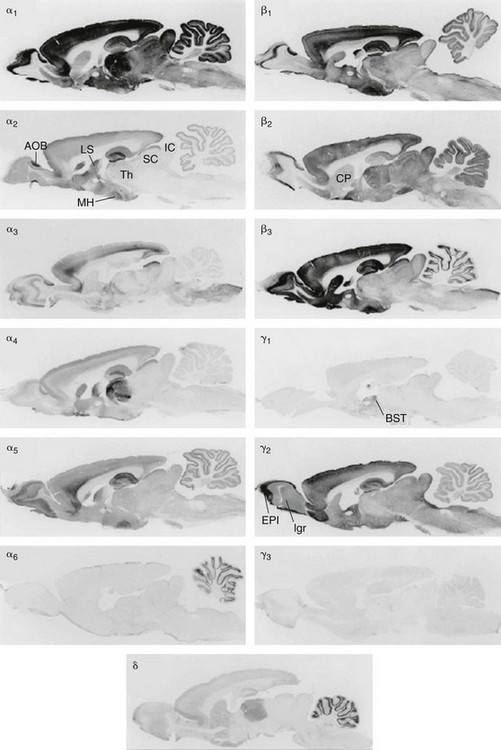

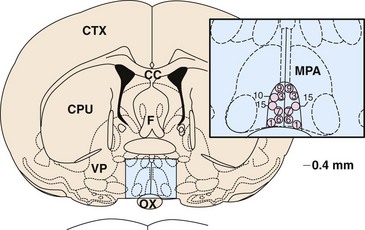

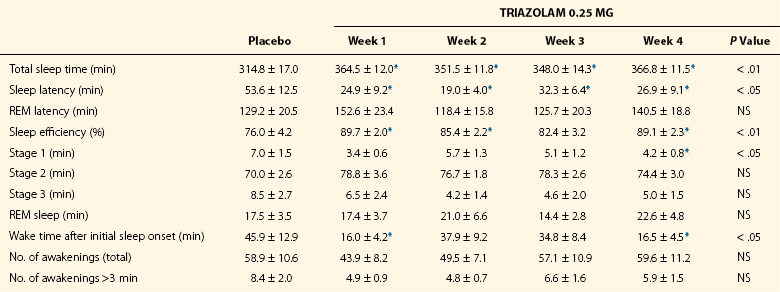

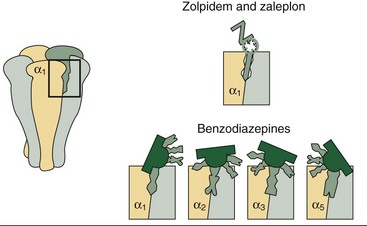

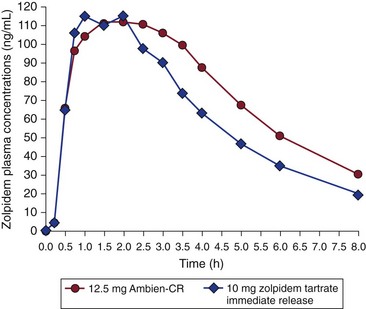

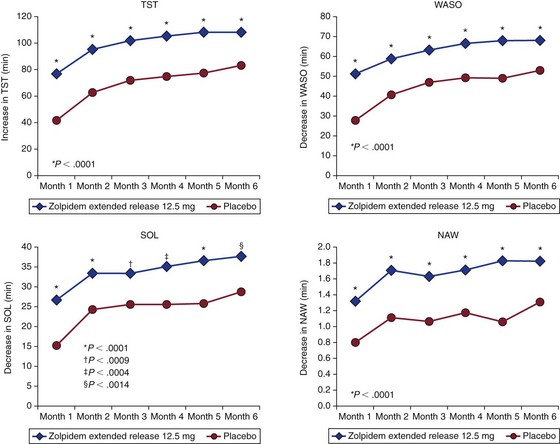

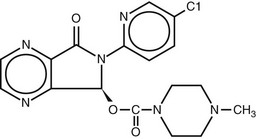

Chapter 6 The modern era of hypnotic pharmacology began in the 1960s with the introduction into the U.S. market of the benzodiazepines, or diazepam-like compounds, which dominated the market until the development of the newer, nonbenzodiazepine agents in the 1990s (Table 6-1). Table 6-1 Includes data from Wilson S, Nutt DJ: Sleep disorders. New York, 2008, Oxford University Press. All of the current FDA-approved agents—with the exception of ramelteon and doxepin—act by modulating the function of the γ-amino butyric acid (GABA)-A receptor complex. This complex is composed of five glycoprotein subunits, each of which comes in multiple isoforms (Fig. 6-1). Figure 6-1 Schematic representation of the GABA-A receptor complex. Hypnotic activity that results from GABA receptor–modulating compounds appears to be related to action at the α1 and possibly the α3 isoforms. Distribution of these isoforms is seen in Figure 6-2, their putative actions are seen in Figure 6-3, and the relative affinities of GABA agonist hypnotics for these isoforms are seen in Table 6-2. Table 6-2 Relative GABA-A Receptor Affinities of Commonly Used Medications Modified from Nutt DJ, Stahl SM: Searching for perfect sleep: the continuing evolution of GABA-A receptor modulators as hypnotics. J Psychopharmacol 2010;24(11):1601–1612. Figure 6-2 Immunocytochemical distribution of GABA-A receptor subunits α1 through α6, β1 through β3, γ1 through γ3, and δ in sagittal sections. The neuroanatomic site of action of hypnotics has not been fully elucidated. Among the important sites for agents that act at the GABA-A receptor are the medial preoptic area (MPA) and ventrolateral preoptic area (VLPO) of the hypothalamus. Microinjections of a variety of agents—such as triazolam, pentobarbital, ethanol, adenosine, and propofol—into the MPA induce sleep in animal studies (Fig. 6-4). Figure 6-4 Typical injection sites of triazolam into the medial preoptic area (MPA) in rats. Figure 6-5 illustrates triazolam as representative of the benzodiazepines; Table 6-3 details triazolam’s effects on sleep. Table 6-3 Effects of Triazolam on Polygraphic Measures of Sleep in a 4-Week Trial NS, not significant; REM, rapid eye movement. *Differs from placebo condition by at least P < .05 (least significant difference test). Data from Mendelson WB: Subjective vs. objective tolerance during long-term administration of triazolam. Clin Drug Invest 1995;10:276–279. Beginning with zolpidem in the early 1990s, the newer non-benzodiazepine GABA-A receptor modulators are more selective in their binding to α-isoform subtypes than are the benzodiazepines, as seen in Figures 6-6 and 6-7. Although as a class their effects on sleep appear relatively more specific than with the benzodiazepines, it should be cautioned that they may have other types of effects, such as on body balance. One meta-analysis indicates that whereas benzodiazepines and zopiclone produce significant next-day driving impairment, zolpidem 10 mg and zaleplon 10 mg had relatively little effect; other work suggests that zolpidem 10 mg may also have residual driving effects in the elderly. Figure 6-6 Binding of benzodiazepines, zolpidem, and zaleplon to the α-subunit of the GABA receptor. Zolpidem comes in its original immediate-release form, now generic in the United States, as well as in a modified-release, two-layer tablet (Ambien CR; Figs. 6-8 and 6-9). A sublingual form (Intermezzo) is designed for administration during awakenings at night, when the patient plans to be in bed for at least an additional 4 hours, and it significantly decreases the time it takes to return to sleep. This strategy of taking a medication in the middle of the night to return to sleep should be reserved for people who wake up in the middle of the night and have difficulty returning to sleep on an intermittent, unpredictable basis. In such cases, as-needed use is superior to nightly prophylactic dosing, which is associated with dosing on many nights when medication is not needed, thereby exposing patients to unnecessary costs and side effects. However, for those with nightly or near-nightly difficulty with middle-of-the-night awakenings, nightly dosing with an agent intended to prevent these awakenings is indicated. Figure 6-8 Plasma concentrations following administration of zolpidem two-layer, modified-release (Ambien-CR) 12.5 mg and zolpidem 10 mg. Figure 6-9 Sample efficacy data for zolpidem modified-release 12.5 mg given 3 to 7 nights per week over 6 months. Zopiclone and eszopiclone are addressed in Figures 6-10 through 6-12. Figure 6-10 Structure of eszopiclone, the S-isomer of racemic zopiclone. (From data on file, Sepracor Inc.)

Pharmacology

Drugs with Hypnotic Properties

The sites at which a variety of sedative/hypnotics and anesthetics act are indicated. (Modified from Rudolph U, Mohler H: Analysis of GABA-A receptor function and dissection of the pharmacology of benzodiazepines and general anesthetics through mouse genetics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2004; 44:475–498.)

The α1 subunit, which is believed to be associated with sleep induction and memory effects, is found throughout the brain, although in varying concentrations in different regions. Types α2 through α6 are localized in more specific brain regions. Some hypnotics, notably eszopiclone, also have significant activity at the α3 subunit. Scale bar = 2 mm. AOB, accessory olfactory bulb; BST, bed nucleus ofstria terminalis; CP, caudoputamen; EPI, external platform layer of the olfactory bulb; Igr, internal granular layer of the olfactory bulb; IC, inferior colliculus; LS, lateral septal nucleus; MH, medial hypothalamic nuclei; SC, superior colliculus; Th, thalamus. (Modified from Pirker S, Schwarzer C, Wieselthaler A, et al: GABA-A receptors: immunocytochemical distribution of 13 subunits in the adult rat brain. Neuroscience 2000;101:815–850.)

Injection in these sites produced shortened sleep latency and increased total sleep, whereas injections into surrounding areas had no effect. CC, corpus callosum; CPU, caudate putamen; CTX, cortex; F, fornix; OX, optic chiasm; VP, ventral pallidum. (Modified from Mendelson WB, Monti D: Effects of triazolam and nifedipine injections into the medial preoptic area on sleep. Neuropsychopharmacology 1993; 8:227–232.)

Zolpidem

The benzodiazepines, such as triazolam and estazolam, bind to all of the α-unit isoforms of the GABA-A receptor complex, which may explain why they have a wide range of pharmacologic effects in addition to sleep induction. The newer nonbenzodiazepine GABA receptor agonists such as zolpidem have relatively greater selectivity for the α1 subunit, which may correspond to their higher ratio of sleep/nonsleep effects. (Modified from Sleep: excessive sleepiness. San Diego, 2005, NEI Press. Copyright Neuroscience Education Institute, reprinted with permission.)

Note the higher plasma concentrations of the modified-release preparation in the second half of the night. (Data from Amin J, Lee A, Gerlovin M, German D [eds]: Monthly prescribing reference: diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. Prescribing Reference, 2006. Available at www.empr.com.)

Data taken from a patient’s morning questionnaire. NAW, number of nocturnal awakenings; SOL, sleep onset latency; TST, total sleep time; WASO, wake after sleep onset. (Data from Krystal A, Erman M, Zammit GK, et al: Long-term efficacy and safety of zolpidem extended-release 12.5 mg, administered 3 to 7 nights per week for 24 weeks, in patients with chronic primary insomnia. Sleep 2008;31:79–90.)

Zopiclone and Eszopiclone

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Pharmacology

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue