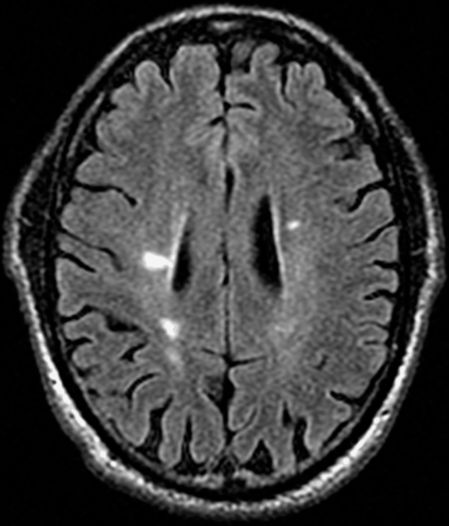

Axial FLAIR MRI brain showing ovoid, periventricular and juxtacortical lesions also involving the corpus callosum highly characteristic of MS lesions in this patient without classical clinical features of MS.

Repeat brain MRIs continued to show areas of abnormal signal but no interval development of any new lesions. There were juxtacortical lesions, a subcortical lesion in the left hemisphere white matter and a posterior left frontal lobe lesion. Cervical and thoracic spine MRI scans were normal with no evidence of demyelination within the spinal cord. Somatosensory evoked potentials were normal. EMG and nerve conduction studies were normal.

Three-step assessment

1 Classical clinical features of MS: none

2 Neurological examination: normal

3 Investigations: MRI brain consistent with MS; MRI spinal cord normal; CSF abnormalities (elevated IgG index) consistent with MS

Diagnosis: Radiologically isolated syndrome (RIS).

Tip: A detailed clinical history should check for classical cardinal clinical features for suspected relapses of multiple sclerosis or of a progressive neurological deficit consistent with progressive multiple sclerosis. The absence of these clinical features, along with highly characteristic brain and/or spinal cord MRI lesions, is consistent with a diagnosis of RIS.

The radiologically isolated syndrome is a relatively recent concept. Research groups studying this have shown that the risk of developing one clinical attack consistent with multiple sclerosis is approximately 30–35 percent within the first five years of evaluation. As was the case in the presented history, MRI scans are generally recommended for such procedures as migraine headache evaluation, routine follow-up for executive clinical evaluation, being a control in an investigational MRI study, and investigation of other nonspecific symptoms. Patients with asymptomatic typical demyelinating lesions within the spinal cord are at a higher risk for a future clinical attack than those without spinal cord MRI lesions. Currently, immunomodulatory MS medications are not generally recommended for this patient group.

Case 8: A patient with fatigue and a history of remote neurological symptoms, but without significant neurological debility. Could this be benign MS?

Some patients appear to have rather “benign” forms of multiple sclerosis. Definitions of this MS clinical course differ; however, it is often loosely defined as a lack of significant neurological impairment at least 15 to 20 years following the onset of multiple sclerosis. This should be distinguished from radiologically isolated syndrome, where there are no classical symptoms of clinical MS attacks but highly typical MRI features are found incidentally. In benign multiple sclerosis, patients definitively have multiple sclerosis with at least one prior attack and new MRI lesions occurring but seem to accrue little or no impairment with or without immunomodulatory medications, even after decades of having the disease. Benign multiple sclerosis remains controversial as MS-related cognitive impairment may be underreported, and long-term follow-up in some patients is limited to fully assess this.

A 67-year-old gentleman presented because of troublesome fatigue. He came with an existing “possible” diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. In the 1970s, the patient experienced an episode of painless, binocular diplopia lasting three months with resolution. In 1980, the patient developed a Lhermitte symptom accompanied by a sense of leg heaviness. Since then, he described waxing and waning sensory symptoms including tongue burning and numb spots on the face, left lower abdomen and left foot. There were other widely distributed patches of sensory symptoms that were rare and difficult to describe. There was no recent history to suggest any classical clinical relapses of multiple sclerosis. He was very active and was able to run without difficulty and walk for miles without any gait impairment.

On neurological examination his mental status was found to be normal, as were his visual fields. Extraocular movements were also entirely normal, with no internuclear ophthalmoplegia. A motor exam was entirely normal and plantar responses were flexor bilaterally.

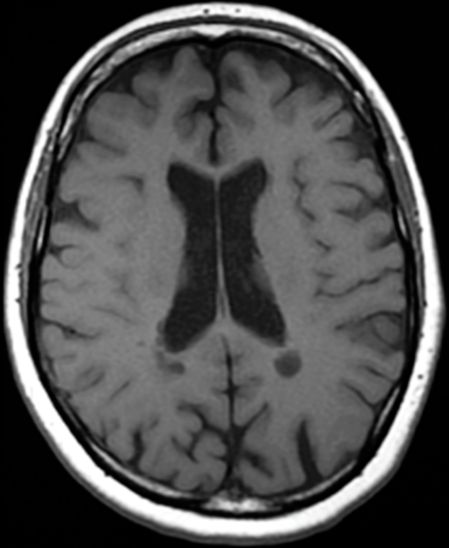

A brain MRI showed multiple areas of abnormal signal highly consistent with MS, and was unchanged from a brain MRI performed fifteen years previously (Figure 2.2). There was little or no change in the number, size or signal intensity of the lesions seen. A spinal cord MRI showed a small focus of abnormal T2 signal intensity at the C2–C3 level consistent with multiple sclerosis (not shown).

Axial FLAIR MRI brain showing scattered T2 hyperintensities, predominantly within the periventricular white matter compatible with clinical diagnosis of multiple sclerosis.

Three-step assessment

1 Classical clinical features of MS: brainstem attack with diplopia, Lhermitte symptom with cervical myelopathy

2 Neurological examination: normal

3 Investigations: MRI brain and cervical spine consistent with MS; CSF not performed

Diagnosis: Benign relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis.

Tip: Despite experiencing few problems over many decades, the patient clearly has relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, which is confirmed by his clinical history as well as MRI investigations. MRI scans compared with many years before may show little or no ongoing or intervening inflammatory activity in those with benign MS. Patients may go many years or decades without clear significant neurological impairment or confirmed secondary progressive multiple sclerosis.

Case 9: MS with occasional symptomatic worsening. Is it relapsing-remitting or a progressive clinical course of MS?

Pseudo exacerbations are temporarily worsened old MS symptoms that occur in association with increased body temperature, fatigue, infection or stress. This is a heralding of old symptoms due to inactive demyelinated multiple sclerosis plaques rather than an acute inflammatory attack of multiple sclerosis. Pseudo exacerbations of multiple sclerosis may occur with most MS clinical courses but are particularly common in patients with progressive forms of multiple sclerosis of long disease duration who have established disability. Occasionally the symptoms may be significant and prolonged. Treatment aimed at curing infection or reducing body temperature and returning to baseline neurological status is important but this does not constitute new inflammatory relapses of MS.

A 57-year-old woman had initial symptoms of multiple sclerosis with loss of sensation in her lower extremities for three weeks with spontaneous resolution at age 30 following the birth of one of her children. A brain MRI scan and CSF examination were convincing for the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. One sister had MS and used a walker.

She did not recall symptoms of prior optic neuritis nor of diplopia, and could not recall other definite attacks over time since the post-partum period. She had symptoms and signs of neurogenic bowel and bladder dysfunction. She described a steady decline in her gait due to progressive motor weakness over a number of years. She started to use a walker five years ago. She did not use a cane before that, but she did have significant imbalance. She now uses a scooter and a wheelchair at home. She had initiated treatment with interferon beta-1b, which she has remained on for ten years. She has had therapeutic intolerance with significant injection site reactions, and expressed a desired to discontinue immunomodulatory MS medications.

On examination, her mental status was normal. Her cranial nerves were normal, and her speech was clear. On motor examination, she had weakness on the right greater than left upper and lower extremities in an upper motor neuron “pyramidal” distribution. Reflexes were brisker on the right than left, and her plantar responses were extensor bilaterally. Vibratory sense was impaired in the lower extremities. She walked with a markedly impaired spastic ataxic gait, right more than left, and required a walker for standing.

A brain MRI remained entirely stable with areas of abnormal signal consistent with multiple sclerosis, as serial brain MRIs from the past had shown (Figure 2.3). A cervical spinal cord MRI showed areas of abnormal T2 signal without gadolinium-enhancing lesions, which is consistent with chronic demyelination of multiple sclerosis.

Axial T1 MRI brain showing chronic, inactive, ovoid areas of T1 hypointensity (“black holes”) consistent with chronic MS; multiple focal and confluent areas of hyperintense T2 signal change were also seen, as well as hyperintense T2 signal change within the pons (not shown).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree