Axial T2 MRI brain showing abnormal focal T2 signal abnormalities within the pons and cerebellar peduncles and axial FLAIR MRI showing extensive, non-enhancing increased T2 signal in the periventricular white matter directly abutting the ventricles.

Three-step assessment

1 Classical clinical features of MS: optic neuritis, progressive hemiataxia (bilateral)

2 Neurological examination: asymmetrical limb ataxia (cerebellar outflow tremor)

3 Investigations: MRI brain consistent with MS

Diagnosis: Secondary Progressive MS with progressive cerebellar impairment.

Tip: A cerebellar outflow tremor due to MS is notoriously difficult to treat symptomatically but benzodiazepines and gabapentin are often recommended.

Case 45: A woman with progressive cerebellar ataxia and an isolated cerebellar lesion. Is it MS?

A 71-year-old woman was well until two years prior to presentation. At that time, she had a relatively acute onset of vertigo and gait impairment. She continued to have worsening symptoms following the onset with progressive gait impairment. A brain MRI identified an enhancing lesion in the cerebellar hemisphere. She initiated treatments on corticosteroids, and a cerebellar biopsy was subsequently performed that was pathologically non-diagnostic, with evidence of gliosis but no neoplasm.

Since that time, she suffered from worsening incoordination of the right upper extremity. She had developed intractable hiccups, occasional diplopia and progressive truncal ataxia with worsening gait impairment. She initially started to use a walker but now required a wheelchair for ambulation. She had tapered off the corticosteroids entirely and had a brief course of cerebellar irradiation despite the lack of clear diagnosis. She had a 33-pack-per-year history of cigarette smoking. There was no family history of MS or other autoimmune CNS diseases.

On neurological examination she was awake and alert. She was severely debilitated, however, by the truncal ataxia. She had gaze-evoked horizontal nystagmus with macro square-wave jerks but no downbeat nystagmus. There was no palatal myoclonus. Motor examination was normal apart from being deconditioned. Plantar responses were flexor bilaterally. She had a tremor in the right greater side than on the left, with incoordination of both the upper and lower extremities and severe truncal ataxia which meant she found it difficult to even sit upright.

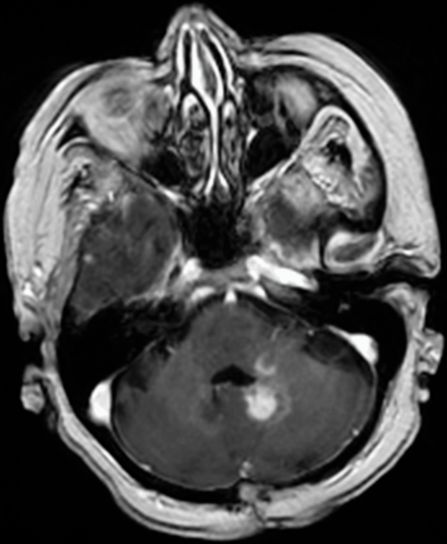

A repeat brain MRI showed a continuing area of abnormal T2 signal with gadolinium enhancement (Figure 7.2). A CSF examination was found to be normal. CT scans of the chest, abdomen and pelvis were also normal. Repeat cerebellar biopsies demonstrated a low-grade astrocytoma with features consistent of a pilocytic astrocytoma (WHO grade I).

Axial T1 with gadolinium, an MRI brain showing an abnormal enhancing lesion within the left cerebellar hemisphere centered on the dentate nucleus and extending into the left middle cerebellar peduncle and left side of the brainstem.

Three-step assessment

1 Classical clinical features of MS: progressive cerebellar ataxia

2 Neurological examination: consistent with cerebellar disease

3 Investigations: MRI brain not consistent with MS; MRI spinal cord not consistent with MS; repeat biopsy diagnostic of low-grade astrocytoma, pilocytic astrocytoma

Diagnosis: Cerebellar pilocytic astrocytoma (WHO grade I).

Tip: The patient had impairment restricted to the cerebellum only that was progressive over time. Despite the initial biopsy being unremarkable, she continued to worsen with severe gait impairment. A repeat brain biopsy may be needed in patients where the initial biopsy was felt to be non-diagnostic and there is continued progressive worsening.

Case 46: A young gentleman with acute onset of severe ataxia

A 27-year-old gentleman reported very brief episodes of true spinning vertigo lasting five to ten seconds in duration and which occurred while he was standing. He had no nausea, vomiting, tinnitus, dysarthria or dysphagia. He would have one episode per day and never more than that for the initial two weeks. He then awoke one morning with worsened and more persistent vertigo and painless, binocular, vertical diplopia. He then had progressive gait ataxia and dysarthria over three days. He was hospitalized and treated with intravenous corticosteroids for five days with initial symptomatic improvement. He then continued to deteriorate with more significant gait ataxia, dysarthria and diplopia. He had no cognitive impairment, visual loss, motor weakness, sensory loss or Lhermitte symptoms, or bowel or bladder dysfunction.

He had no prior neurological symptoms, no skin rash and no recent contact with anyone ill. He had no insect or tick bites and no farm animals or toxin exposures. There was no family history of neurological disease.

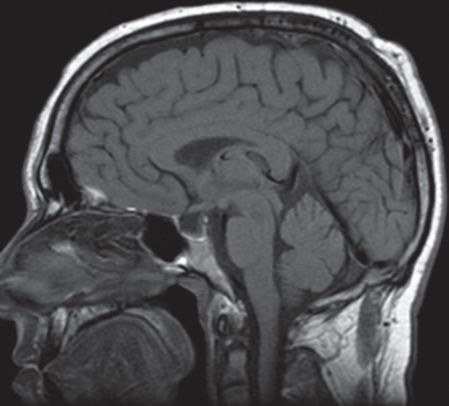

A brain MRI showed a subtle increased T2 signal in the folia of both cerebellar hemispheres without contrast enhancement, mass effect or atrophy (Figure 7.3). A CSF examination showed 28 white blood cells with 83 percent lymphocytes, a protein of 40 mg/dL with negative oligoclonal bands and normal IgG index. Visual evoked potentials were normal. Infectious agents and a serum paraneoplastic antibody screen were negative. Chest, abdomen and pelvic CTs and a scrotal ultrasound were negative for neoplasms. A cerebellar biopsy showed findings consistent with acute cerebellar degeneration with marked Purkinje cell loss associated with Bergmann gliosis, white matter and molecular cell layer gliosis with scattered reactive T-lymphocytes. Microglial activation was observed without microglial nodules.

Sagittal T1 MRI head demonstrates subtle associated elevation of T1 signal on pre-contrast images with no definite contrast enhancement, mass-effect or atrophy. Subtle, but definite, high T2 signal involving the folia of both cerebellar hemispheres, left greater than right, was seen on FLAIR imaging (not shown). Diagnostic considerations include paraneoplastic syndromes and infectious and post-infectious cerebellitis.

A follow-up brain MRI one year later showed interval progression of cerebellar atrophy without abnormal gadolinium enhancement and no other abnormalities.

Three-step assessment

1 Classical clinical features of MS: cerebellar ataxia, binocular painless diplopia

2 Neurological examination: severe, isolated cerebellar ataxia

Diagnosis: Acquired, presumably autoimmune, acute cerebellitis with subsequent cerebellar degeneration.

Tip: The acute and severe impairment in this patient with completely isolated involvement of the cerebellum is inconsistent with MS and consistent with cerebellitis. The brain MRI findings did not show typical white matter disease characteristic of MS, but instead showed an abnormality in the cerebellar folia. The CSF examination was consistent with an acute probable inflammatory cause and serology did not define an infectious cause. A cerebellar biopsy ruled out neoplastic and other causes. A follow-up brain MRI confirmed subsequent isolated cerebellar involvement with severe atrophy.

Case 47: An older gentleman with progressive gait ataxia and an abnormal brain MRI

A 69-year-old gentleman presented with a one- to one-and-half-year history of slowly progressive gait instability and personality changes. He started to develop problems, suffering from falls which always occurred while he was doing something active, such as lifting heavy items or mowing the lawn. He said that he feels like he is going to fall and that he cannot catch himself. He reports no worsened problems when walking in the dark. He has had occasional anger outbursts, which his wife says was very unusual since he has always been very laid back. He had not displayed any dream enactment behavior or nocturnal stridor. One month of oral corticosteroid therapy did not produce any improvement in the symptoms.

On examination there was no significant orthostatic hypotension. He scored 33/38 on a Kokmen short test of mental status. His speech was dysarthric and of a mixed ataxic, spastic and hypophonic character. A motor exam was found to be normal, as were reflexes with bilateral flexor plantar responses. He had moderate vibratory loss in the distal bilateral lower extremities. He had mild bilateral appendicular ataxia with a wide-based ataxic gait.

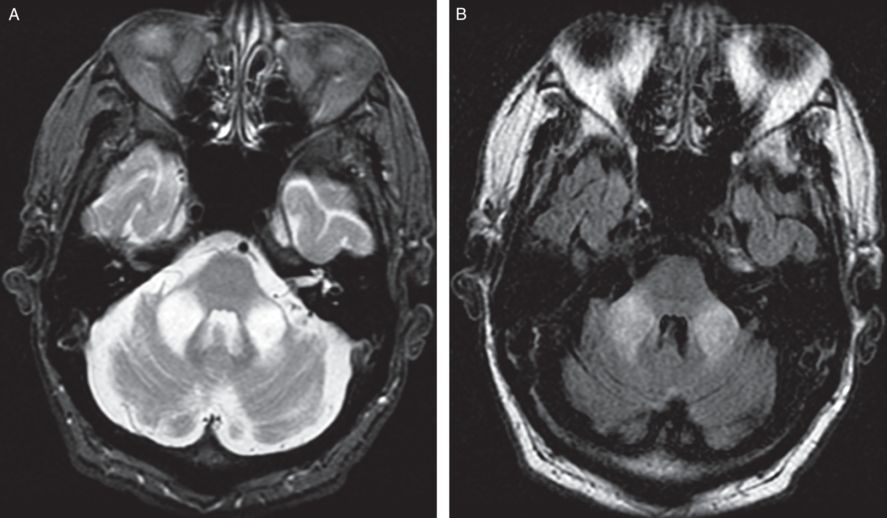

A brain MRI showed symmetrical T2 signal abnormality involving the middle cerebellar peduncles bilaterally with mild atrophy of the midbrain, medulla and cerebellum (Figure 7.4). A CSF examination was normal. Serum testing for Lyme and paraneoplastic disorders was negative. Genetic testing for dominantly inherited spinocerebellar ataxias was negative. Further testing showed an abnormality of the FMR-1 gene. An expanded CGG repeat of 88 was detected, indicating he is a carrier of Fragile X syndrome. Southern blot analysis suggested a normal methylation pattern. The finding of 88 CGG repeats and normal methylation pattern suggests the presence of a premutation within the Fragile X gene.

Axial T2 and FLAIR MRI brain demonstrates non-enhancing, symmetrical T2 signal abnormality involving the middle cerebellar peduncles bilaterally with mild atrophy of the midbrain, medulla and cerebellum.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree