Sensory level described by patients with myelopathies.

Step 2: Conduct a neurological examination for signs of MS

See Table 1.2.

| Examination | Examination findings | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Dementia | Impaired cognition on mental status exam | Pitfall: non-specific memory concerns are common in MS but not reliably distinguishing; severe dementia is uncommon but occurs in MS |

| Optic neuropathy | Scotoma, acuity deficit, color vison impairment, relative afferent pupillary deficit | Pitfall: acuity deficit due to refractive errors |

| Internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO) | May be bilateral, often incomplete with slowed adduction and dysconjugate nystagmus | Rapid saccades back and forth from extreme horizontal gaze identifies INO |

| Limb ataxia | Often asymmetrical | Pitfall: palatal myoclonus is a feature of stroke and Alexander disease |

| Upper motor neuron weakness | Pyramidal distribution; extensor plantar responses (Babinski signs) | Bilateral extensor plantar responses strongly suggest a myelopathy |

| Sensory loss | In pattern of cortical, brainstem or spinal cord impairment | Distal lower extremity vibratory loss most sensitive; pitfall: pin, light touch sensation is highly subjective and better appreciated on clinical history rather than findings on examination |

| Gait | Spastic, ataxic quality is most common, often asymmetrical | Pitfall: some patients have functional non-neurological gait disorders, or are impaired by pain |

The second step in diagnosing multiple sclerosis, following a detailed evaluation for the classical clinical symptoms of MS, is a comprehensive neurological examination. One way to simplify the results of neurological evaluation is to classify it as normal neurological examination, neurological examination consistent with multiple sclerosis or neurological examination consistent with an alternative neurological disease as the etiology. It should be strongly emphasized that many MS patients will have an entirely normal neurological examination. A neurological examination consistent with MS means that they exhibit one or more characteristic, but not defining or pathognomonic, abnormalities. For instance, patients may have signs of optic neuropathy such as visual acuity impairment, central scotoma, color vision impairment and a pale optic disc, all of which are characteristic of MS, particularly if the patient has a clinical history of typical optic neuritis. Extraocular movement abnormalities such as unilateral or bilateral internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO) indicative of interruption of the brainstem medial longitudinal fasciculus connecting the oculomotor and contralateral abducens nerve are classically caused by MS. It should be noted, however, that INO due to MS is often incomplete and the identification of slowed adduction with dysconjugate nystagmus is best seen by having the patient make repeated, rapid saccades back and forth from one extreme horizontal gaze to the other. Findings of corticospinal tract impairment with upper motor neuron–type weakness (hyperreflexia, “pyramidal” distribution weakness, extensor plantar responses [Babinski signs]) are commonly found in MS. MS patients may also have signs of cerebellar dysfunction with gait and limb ataxia as well as a cerebellar dysarthria. Distal upper or lower extremity sensory loss particularly to vibration is characteristic of dorsal spinal cord dysfunction in MS.

Step 3: Assess investigational evidence of MS

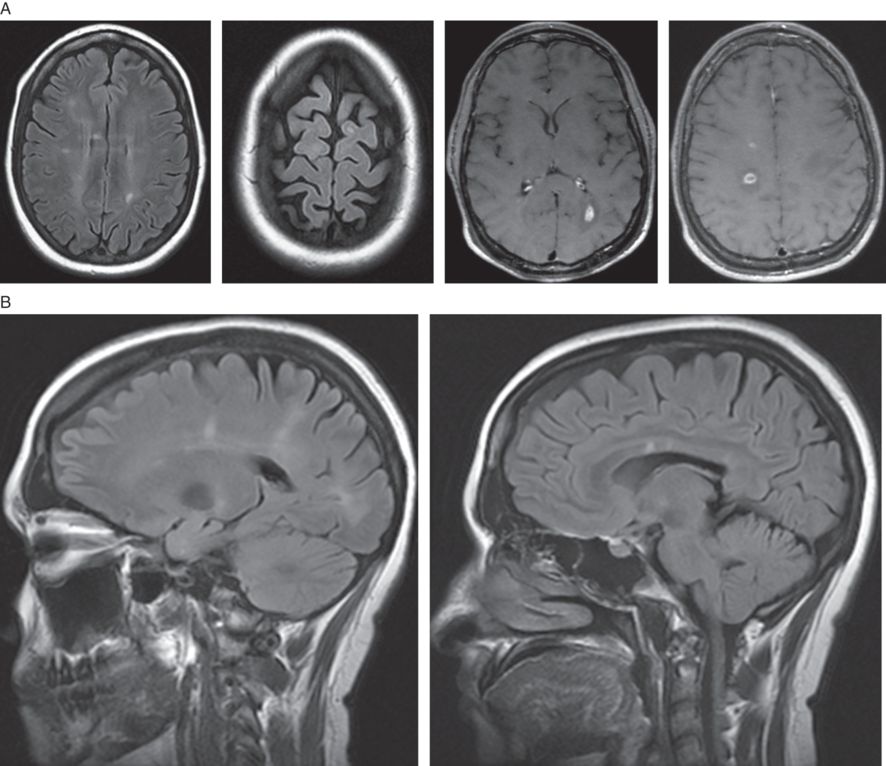

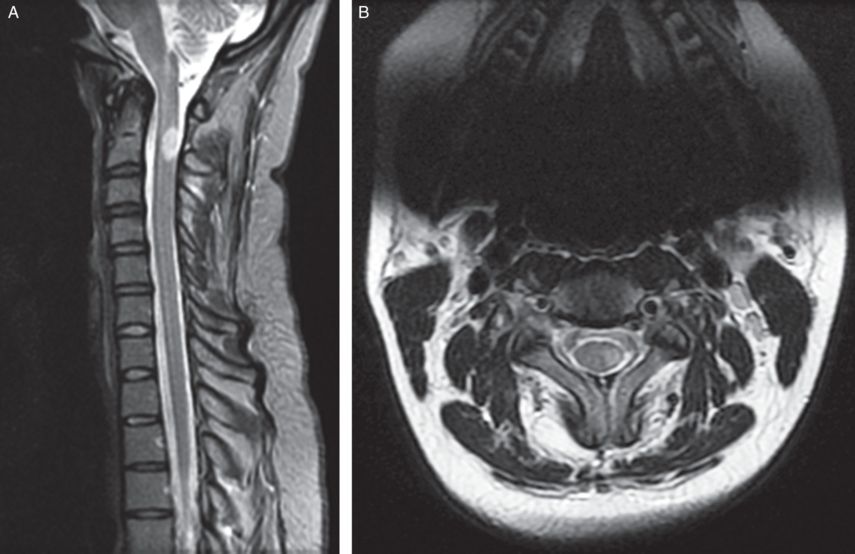

The third step in diagnosing MS is evaluating the results of appropriately selected investigations (Table 1.3). The most sensitive way to investigate a possible diagnosis of MS is the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, cervical, and thoracic spinal cord. Typical ovoid T2-weighted hyperintense lesions located periventricularly within the brain, within the posterior fossa, juxtacortically, chronic T1-weighted hypointense lesions (“black holes”) and acute T1 lesions that enhance following gadolinium administration are particularly characteristic of multiple sclerosis (see Figure 1.2). Similar areas of ovoid abnormal T2 signals that are short in length and generally laterally placed are found within the cervical and thoracic spinal cord (Figure 1.3). While it is extremely common to find non-specific MRI lesions within the brain, such as those related to aging, migraine headaches, hypertension and other vascular risk factors, these types of typical T2 lesions within the cervical and thoracic spine are characteristic of multiple sclerosis and do not arise simply due to these conditions.

|

A) Axial MRI brain showing typical FLAIR periventricular, juxtacortical and T1 gadolinium–enhancing lesions. B) Sagittal MRI brain FLAIR sequence showing typical “Dawson’s fingers” and corpus callosum MS lesions.

Sagittal T2 MRI cervical spine dorsally placed, short-segment, ovoid lesion characteristic of multiple sclerosis. Axial T2 MRI cervical spine in the same patient shows the lesion is in the left lateral aspect of the spinal cord.

The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination remains an important diagnostic test in the evaluation of MS. In particular, CSF elevations in the immunoglobulin G (IgG) index and unique CSF oligoclonal bands are characteristic of an immune-mediated CNS disease process generally and often of multiple sclerosis specifically. Examination of the white blood cell count, protein levels and other values are of benefit, but generally only to rule out mimickers of multiple sclerosis, including CNS infectious diseases, CNS neoplasms or other non-MS CNS diseases.

Electrophysiological evaluation of CNS pathways with evoked potentials also assists in MS diagnosis. Visual evoked potentials (VEP) assess for conduction deficit in the optic nerves. Somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEP) may identify impaired conduction in the central proprioceptive pathways. Brainstem auditory evoked potentials (BAEP) may, in rare cases, be useful in identifying central versus peripheral hearing impairment in the evaluation of multiple sclerosis.

Serological and neuroradiological testing, as well as other selected investigations searching for infectious, vascular, traumatic, neoplastic, inherited and other causes that may mimic multiple sclerosis, may be required in cases where a diagnosis of MS remains uncertain (see Table 1.4). Many MS cases are straightforward and few if any investigations outside of MRI, CSF and evoked potentials are required.

| Clinical red flags | Implication |

|---|---|

| Headache/meningismus | Sarcoidosis, SLE, Lymphomatosis |

| Stroke-like events | SLE, Antiphospholipid Syndrome, CNS angiitis, embolic strokes |

| Myopathy | Mitochondrial disease, Sarcoidosis |

| Neuropathy | B12 deficiency, Dysmyelinating D/o |

| Diabetes insipidus | Sarcoidosis, Histiocytosis |

| Bone lesions | Histiocytosis/Erdheim Chester disease |

| Pulmonary symptoms | Sarcoidosis, SLE |

| Cardiac symptoms | Embolic cerebral infarcts |

| Mucosal ulcers | Behçet’s disease |

| Arthritis/arthralgia | SLE, Sjögren’s disease |

| Rash | SLE, Fabry’s disease, Lyme |

| Oculomasticatory myorhythmia | CNS Whipple |

| Uveitis | Behçet’s disease, SLE |

| Prominent family history | CADASIL, Hereditary Spastic Paraparesis, Dysmyelinating disorder |

| Endocrinopathy | Sarcoidosis, Histiocytosis |

| Retinopathy | Mitochondrial disease, Susac syndrome |

| Thrombotic events | Antiphospholipid Syndrome, SLE |

| Laboratory red flags | |

| Elevated ESR | Vasculitis, SLE, Sjögren’s |

| High titer ANA | Connective tissue disease |

| Elevated serum lactate | Mitochondrial disease |

| Anemia/cytopenia | SLE, B12 deficiency |

| Persistent/marked CSF pleocytosis | Lymphoma |

| Neutrophilic CSF pleocytosis | Behçet’s disease, CNS Whipple |

SLE – systemic lupus erythematosus, CADASIL – cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy

Case 1: A woman with numbness and prior visual loss: possible MS

A 41-year-old woman noted one day while showering and shaving her legs that her right leg and thigh sensation was gone. This involved the whole limb, both anterior and posterior. The sensory loss then progressed the next day to involve the foot of that lower extremity, her buttocks, her genitalia, and the next day up to the lower back, all on the right side. She then had moderate, but incomplete, spontaneous improvement in the sensation over roughly the next three weeks. She had no left-side impairment, nor any motor weakness or bowel or bladder dysfunction. She had noticed higher levels of fatigue over the previous few months.

She recalled that five years previously, during a stressful time, she had left eye blurriness with mild ocular pain that resolved spontaneously over about three or four weeks. She had had no diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia or hearing loss and no other episodes of visual or sensory impairment. Her ambulation was normal and she could easily walk a mile and recently was able to cycle thirteen miles.

On examination, her mental status was normal, while visual acuity and color vision were normal bilaterally. Her motor exam was normal. A sensory exam revealed decreased temperature sensation up to T5 on the right side, with preserved pin vibratory and joint position sense. Muscle stretch reflexes were normal and her plantar responses were downgoing bilaterally. Her gait was normal.

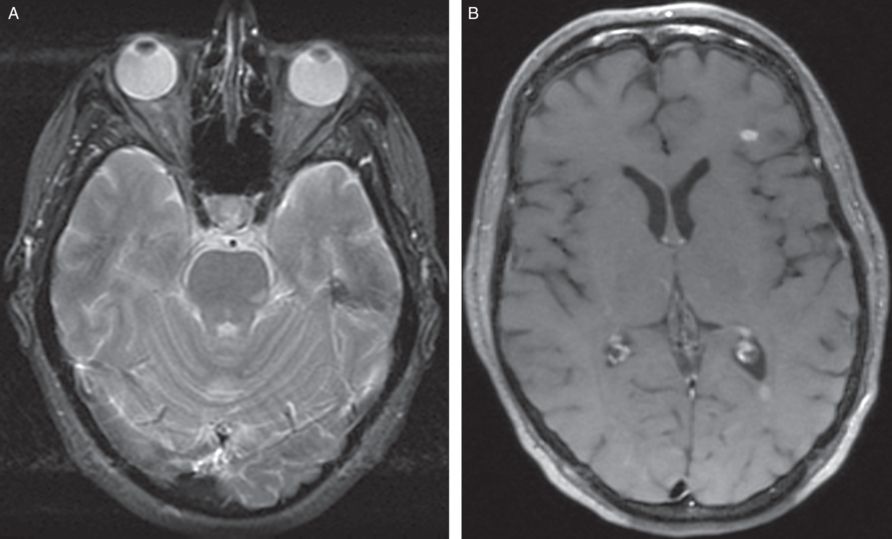

A brain MRI demonstrated areas of radially oriented nonenhancing increased T2 signals within the cerebral hemispheres, and T2 lesions in the cerebellum and pons suggestive of MS. Gadolinium-enhancing lesions were found throughout, raising suspicions of active demyelinating disease (Figure 1.4). A cervical spine MRI was normal. A thoracic spine MRI showed subtle, short segment T2–signal abnormality at T4 (not shown). A CSF examination showed elevations in oligoclonal bands and IgG index and normal other values. Visual evoked potential showed mild slowing on the left visual pathway.

A) Axial T2 MRI brain showing left pontine MS lesion. B) Axial T1 MRI brain with gadolinium showing enhancing white matter lesion in left frontal lobe.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree