Axial FLAIR, coronal T1 with gadolinium MRI brain multiple demyelinating plaques consistent with multiple sclerosis within the white matter of both cerebral hemispheres, with single enhancing focus posterior limb right internal capsule consistent with an acute demyelinating plaque.

Three-step assessment

1 Classical clinical features of MS: painful tonic spasms prior to brainstem attacks

2 Neurological examination: consistent with MS: a gait ataxia with distal vibratory sense loss; paroxysmal spasms observed

3 Investigations: MRI brain consistent with MS with acute demyelinating plaque, CSF consistent with MS

Tip: Paroxysmal painful tonic spasms may be due to CNS demyelination. The stereotyped and repetitive nature of the spells, as well as the frequency (which in this case amounted to up to 45 times per day), is characteristic of this condition, and this frequency may rule out an epileptiform cause as well. Usually the inciting demyelinating lesion is found within the cervical spine, but lesions in the internal capsule, as was the case in this patient, may also cause this symptom. Antiepileptic drugs improve MS paroxysmal spasms and exquisite therapeutic responsiveness to carbamazepine is common. An increased dose of carbamazepine was required in this patient, who subsequently experienced complete elimination of the paroxysmal tonic spasms. Often carbamazepine can be weaned and discontinued successfully after weeks to months of therapy, with the spasms having abated for a prolonged duration.

Case 13: A man with treatment-resistant trigeminal neuralgia

A 64-year-old gentleman was evaluated who had been symptomatic from first and third division right trigeminal neuralgia for six years. Over that period, the painful symptoms had waxed and waned in severity. Triggers such as eating provoked the symptoms and he described the pain as like “lightning,” with a severity estimated at 8/10 on a Likert pain scale. He had been treated with gabapentin and carbamazepine for years on increasing doses as he experienced more frequent, and more severe, lancinating pain episodes. It was considered to be routine trigeminal neuralgia and he came with no prior brain MRI or other neurological diagnosis at the time.

He had no cognitive symptoms or memory loss. He had mild diplopia due to remote trauma at 18 years of age. He had no dysphagia, dysarthria or other cranial nerve symptoms. He had no symptoms of motor weakness, gait difficulties or incoordination or sensory loss.

On neurological examination he had normal cranial nerve examination with mild distal left upper extremity weakness with left hyperreflexia and left extensor plantar response.

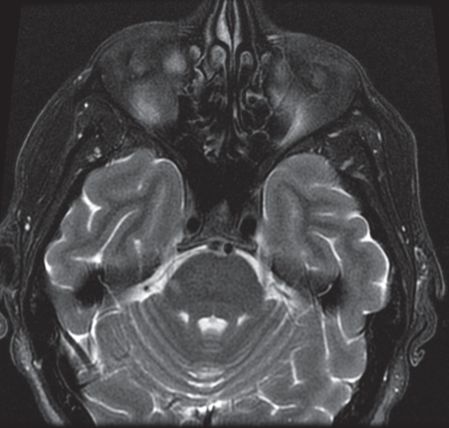

A brain MRI showed T2 hyperintense foci within the cerebral hemispheric white matter with a discrete focus of T2 hyperintensity within the right pons at the trigeminal nerve root entry zone (Figure 3.2). A cervical spinal cord MRI showed non-nenhancing, short-segment T2 hyperintense intramedullary lesions, all of which are consistent with MS.

Axial T2 MRI brain showing prominent white matter lesion within the right aspect of the pons at the root entry zone of the right trigeminal nerve. A number of ovoid T2 hyperintense and T1 hypointense white matter lesions and T2 hyperintense lesions were seen within the cervical spinal cord (not shown).

Three-step assessment

1 Classical clinical features of MS: trigeminal neuralgia

2 Neurological examination consistent with MS: left corticospinal tract impairment (upper motor neuron weakness with extensor plantar response)

3 Investigations: MRI brain consistent with MS with lesion at trigeminal nerve root entry zone; MRI cervical spine consistent with MS

Tip: Trigeminal neuralgia may be the heralding symptom of MS as it was in this presented case. A brain MRI is recommended in all patients with trigeminal neuralgia to identify any vascular compression that causes “typical” primary trigeminal neuralgia, as well as to investigate the possibility of a secondary etiology such as MS as a cause. Trigeminal neuralgia may be bilateral in some MS patients. Surgical management of MS-related TN relies more on ablative therapies rather than vascular decompressive surgery given the etiology of demyelination at the trigeminal nerve root entry zone as opposed to being from arterial compression of the nerve.

Case 14: A man with recurrent spells of ataxia and dysarthria

A 39-year-old man presented with recurrent symptoms of imbalance. Many years ago he had numbness involving the left axilla, trunk and left leg that resolved spontaneously after four days, consistent with an inflammatory sensory cervical myelopathy. He had no prior episodes of ataxia, optic neuritis, diplopia, dysphagia or unilateral motor symptoms. He then developed repetitive and stereotypical spells. For approximately five to ten seconds, he would have an aura that “something is happening.” Following that he would have 30-second spells where his speech would be very “effortful” and slurred, without mental confusion or aphasia. Toward the end of each spell, he would experience left leg and arm tingling paresthesias. The symptoms would always proceed exactly in this stereotyped fashion and occurred repetitively a few times every hour.

He had never awoken from sleep due to these spells and there were no identifiable provoking factors.

His neurological examination was normal.

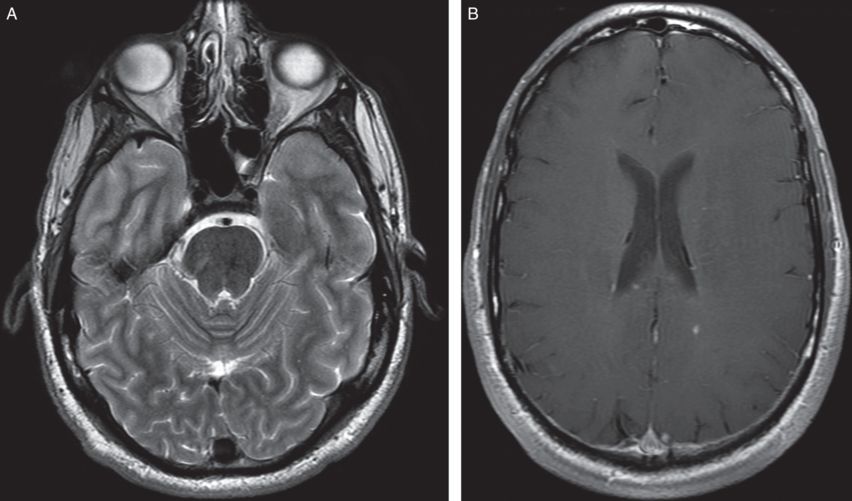

A brain MRI demonstrated multiple white matter T2 hyperintensities, several of which were gadolinium enhancing (Figure 3.3). A cervical spine MRI demonstrated multiple non-enhancing lesions consistent with MS. Thoracic spine MRI and CSF examinations were not performed. EEGs during two typical spells showed no epileptiform activity.

A) Axial T2 MRI brain showing linear signal abnormality in the right pons; patchy T2 signal hyperintensity was also noted within the brainstem around the obex and along the left lateral cervical medullary junction. B) Axial T1 with gadolinium MRI brain with enhancing lesion in right hemispheric white matter.

Three-step assessment

1 Classical clinical features of MS: sensory myelopathy with resolution, paroxysmal ataxia and dysarthria

2 Neurological examination: normal

3 Investigations: MRI brain consistent with MS; MRI cervical spine consistent with MS

Tip: Paroxysmal symptoms of ataxia and dysarthria are an uncommon manifestation of MS. The suspected cause is due to ephaptic transmission (cross talk) over demyelinated axons similar to painful tonic spasms of MS and MS-related trigeminal neuralgia. Typically the location of the MS lesion responsible for this presentation is within the brainstem or cerebellar white matter pathways.

Case 15: Recurrent encephalopathy in a patient with longstanding MS

A 79-year-old woman had a history of MS for over 40 years. Initially she had an attack-related disease, with acute and initially resolving symptoms mostly referable to within the spinal cord. She started to use a cane 38 years ago and had been wheelchair bound for the last 30 years. Over the last 25 years she was unable to transfer independently.

She was evaluated repeatedly in the emergency room for recurrent symptoms of confusion and drowsiness consistent with significant encephalopathy with some hearing impairment and slurred dysarthric speech. During an outpatient visit by her primary care provider a reliable body temperature could not be recorded. She was sent to the emergency room, where an initial body temperature was recorded at 32.1 degrees Celsius. She was rewarmed with IV fluids, and it improved to 35.2 degrees Celsius.

On neurological examination, she had a right internuclear ophthalmoplegia, upper motor neuron quadriparesis and was wheelchair bound.

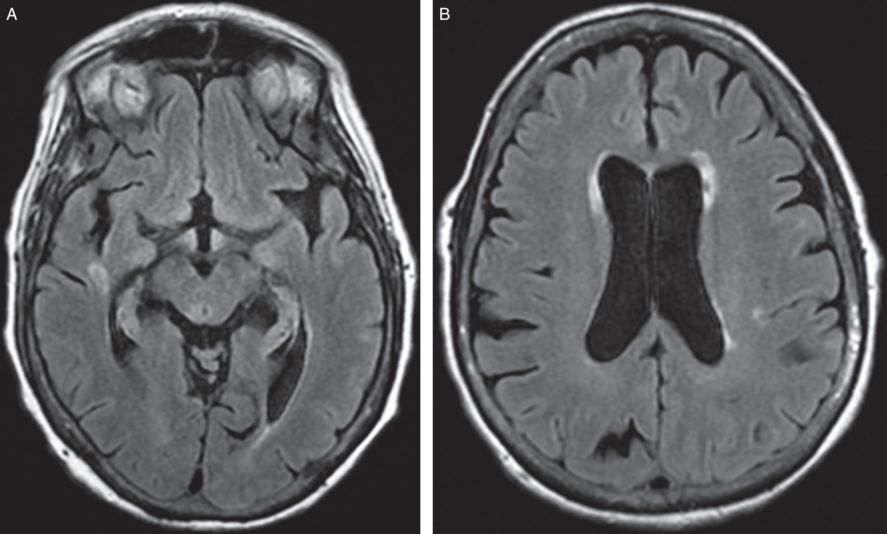

Prior brain and spinal cord MRIs showed typical changes of chronic demyelination due to MS (Figure 3.4). A prior CSF examination showed eight unique CSF oligoclonal bands. A CT angiogram showed no significant abnormalities. An EEG showed atypical triphasic waves and mild slowing posteriorly with no potentially epileptogenic activity consistent with a non-specific encephalopathy.

Axial FLAIR MRI brain showing periventricular signal abnormality consistent with MS. Abnormal multifocal patchy cervical and thoracic cord T2 hyperintensities with focal thoracic cord atrophy consistent with demyelinating disease were also seen (not shown).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree