Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and Sleep

James D. Geyer

Paul R. Carney

Kenneth L. Lichstein

POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

Overview, Epidemiology, and Course

Approximately 1% of individuals in the general population will experience posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in their lifetime (1,2). However, the number of people who have undergone what would be generally experienced as a severe, unexpected, and uncontrollable stressor is much higher than this. Only about 15% to 25% of the individuals who experience the same event develop persistent difficulties that meet the criteria for PTSD (see later) (2). The precipitating and perpetuating factors are poorly understood.

Not all extreme events are believed to be likely to lead to the set of difficulties that characterize PTSD. The current definition according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision, identifies several key aspects of events that tend to cause PTSD (3). These are the threat of death or serious injury that is associated with a response of intense fear, helplessness, or horror. These features are incompletely specified and are not quantifiable phenomena. PTSD is commonly seen in combat veterans, emergency response personnel, and victims of domestic abuse, crime, and trauma.

Avoidance behavior, reexperiencing the trauma, and a persistent hyperarousal are the most common characteristics of the disorder. Most patients develop a general isolation and detachment. Avoidance also includes specific attempts to prevent encountering things that are reminiscent of the traumatic event. The reexperiencing symptoms include recurrent intrusive recollections, nightmares, flashbacks (where individuals have the experience of reliving the traumatic situation), and both central and peripheral hyperactivation in response to events or locations reminiscent of the trauma. Hyperarousal includes disrupted sleep, along with irritability, exaggerated startle, and hypervigilance.

The available data on the natural history of PTSD suggest that it is typically a chronic condition. It has been estimated that 74% of affected individuals continue to have significant symptoms for >6 months (2). Most patients will experience long-term PTSD-associated difficulties regardless of treatment (4).

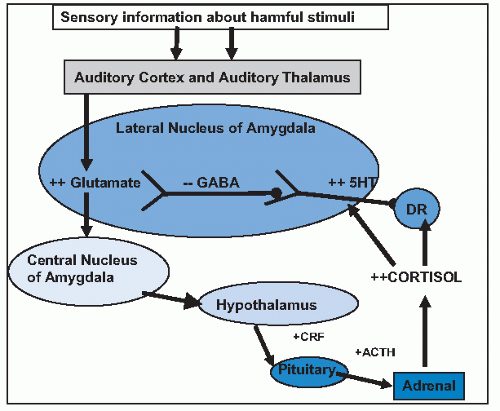

Serotonin (5-HT) plays an important role in the neurobiology of fear-mediated behavior and regulates brain regions implicated in the pathophysiology of PTSD, including the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, locus caeruleus, and hippocampus (5). The amygdala is the central nervous system’s gateway for our freeze-flight-fight response to a perceived threat. 5-HT is involved in the regulation of amygdala firing.

Specifically, 5-HT stimulates inhibitory gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurons, which, in turn, inhibit excitatory glutamate neurons and increase the threshold of amygdala firing (Fig. 26-1). The result is a decrease in vigilance and fear-related behaviors. The ability of 5-HT to modulate glutamatergic activity is dependent on the presence of corticosterone (6,7 and 8).

Clinical studies conducted in subjects with PTSD compared with non-PTSD controls show evidence of 5-HT dysregulation, including (a) decreased platelet 5-HT uptake in most, but not all, studies, (b) blunted prolactin response to the 5-HT releaser, D-fenfluramine, and (c) increased anxiety and heart rate to the serotonergic probe, meta-chlorophenylpiperazine. Perhaps the strongest clinical evidence for 5-HT’s role in PTSD is the positive results from pharmacologic treatment studies with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) resulting in Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of sertraline and paroxetine for the treatment of PTSD. These findings also add support for mirtazapine’s potential efficacy in PTSD given its serotonergic effects, although not via SSRI mechanisms.

Differential Diagnosis

The symptoms that the patient is experiencing must not have been present prior to the trauma. In that case, other diagnoses are indicated. In patients who are predominantly reexperiencing symptoms, obsessive—compulsive disorder is a diagnostic consideration (see later) (3). Flashbacks may be difficult to differentiate from hallucinations that can be seen in schizophrenia, delirium, psychotic mood disorders, substance intoxication, or withdrawal (3). In most cases, it is relatively easy to differentiate these conditions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree