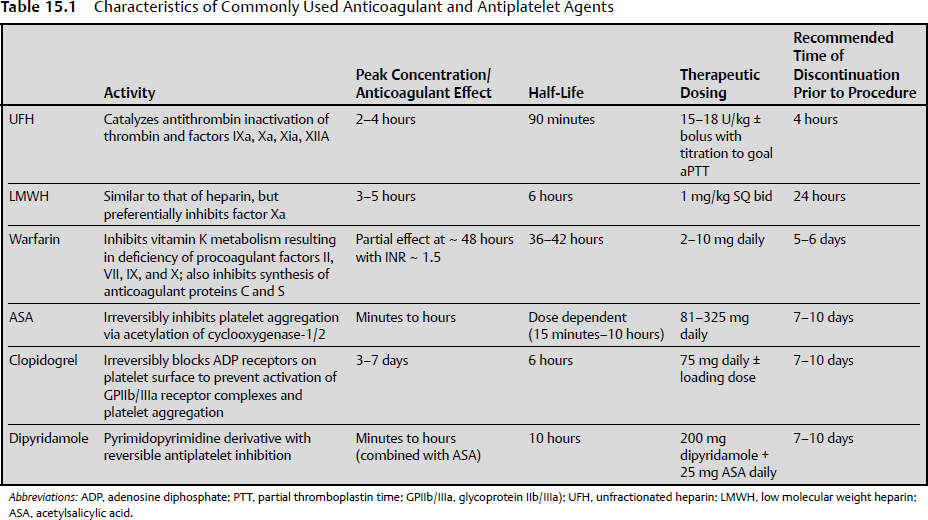

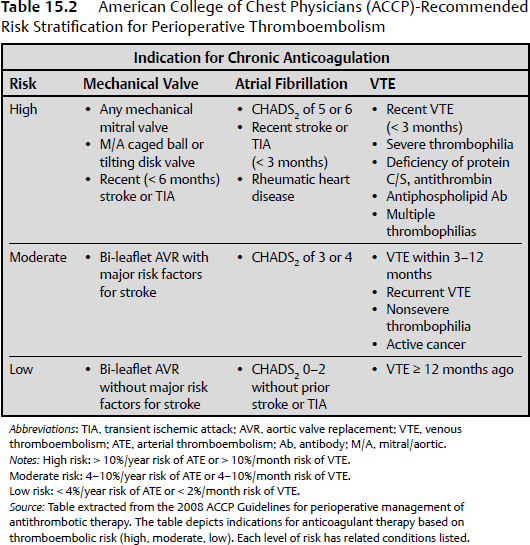

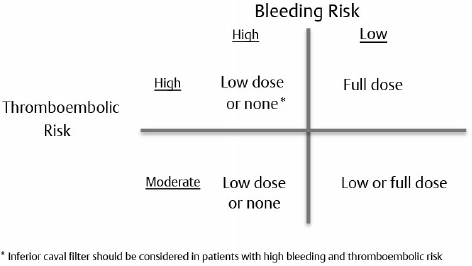

15 Intracranial and spine surgeries are associated with a high risk for bleeding complications. Thus, patients receiving chronic oral anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapies present a significant challenge for the neurosurgeon.1 Many of these patients require bridging therapy and alteration of antiplatelet regimens to minimize the risks of surgical complications. Unfortunately, there is minimal evidence-based literature pertaining to specific guidelines for these patients on appropriate reinitiation of anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy in the postoperative period. Therefore, extrapolation of recommendations presented for nonneurosurgical patients must be considered. The 2008 American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) Guidelines are used to provide a framework for decision making.2 The most recent 2012 ACCP guidelines,3 although changing the way in which quality of evidence and grades of recommendations were established, did not result in any substantive change from the 2008 recommendations. Antiplatelet therapy is used to decrease platelet aggregation and inhibit thrombus formation in the arterial circulation. The most clinically relevant of these drugs are cyclooxygenase inhibitors (aspirin), adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptor inhibitors (clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticlopidine), nonsteroidal anti inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (abciximab, eptifibatide, and tirofiban), and adenosine deaminase and phosphodiesterase inhibitors (dipyridamole). Aspirin and clopidogrel are commonly used for primary and secondary prevention of thrombotic cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease. As these two agents have been widely studied, evidence-based guidelines for reinitiation of therapy are established and will be presented below. As the majority of these other medications are used in the acute setting for treatment of cardiovascular events, perioperative management should be done in conjunction with a cardiologist. Chronic oral anticoagulation (AC) with warfarin is indicated in four primary classes of disorders: cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease (CVD), venous thromboembolism (VTE), and peripheral vascular disease (PVD). PVD includes arterial stenosis and bypass grafts. Patients with a history of upper- and lower- extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE) encompass the VTE group. Those in the CVD group include cardiogenic or atherosclerotic stroke and carotid dissection. Lastly, cardiovascular diseases necessitating anticoagulation include valvular disease with or without prosthetic valves, idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, intracardiac thrombus, and atrial fibrillation.1 Each of these disease subsets represents patients with an increased risk for thromboembolic complications requiring bridging anticoagulation therapy in the periprocedural setting. In fact, the ACCP recommends that those patients with an estimated annual thrombotic risk > 4% in the absence of anticoagulation receive bridging therapy. Pre- and periprocedural strategies for bridging therapy have previously been defined for these patients, but it is important to note that bridging therapy by definition is inclusive of therapeutic unfractionated heparin (UFH) and low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), as well as low-dose LMWH. Postoperative initiation of UFH or LMWH requires individualized assessment of bleeding and thromboembolic risk in all postoperative patients. The delicate balance between perioperative risk of thromboembolism and bleeding is especially prevalent in neurosurgical cases. Ensuring the safety of these high-acuity patients requires great care and consideration of risk stratification, procedure type, and case by case assessment of postoperative bleeding (Table 15.1). The 2008/2012 ACCP guidelines2,3 are considered the authoritative source of recommendations for postoperative resumption of anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy. These guidelines provide recommendations classified by a grading system incorporating assessment of benefit to risk ratio (class 1 and 2), and methodological strength (A through C). Specifically, grade 1 represents strong recommendations such that benefits of therapeutic choice outweigh risk, and grade 2 represents those that are weak, in which the trade off is less clear. Methodological strength is assessed such that high-quality evidence from randomized trials (strength A) is distinguished from moderate-quality evidence from randomized trials with limitations (strength B), and from observational studies with large effects and low quality evidence (strength C).2 All guidelines to date regarding the reinitiation of postoperative anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy are based on grade 1B/C and 2C recommendations. It is well known that there are limited data from randomized controlled studies in this area, as the risk of adverse outcomes in this population far outweighs the possibility of gathering relevant data. This factor highlights the primary importance of evaluating each patient on an individualized case-by-case basis. This evaluation should be based on the degree of postoperative bleeding and level of risk for the development of thromboembolic events. Every neurosurgical patient is considered at high perioperative bleeding risk, and the degree of postoperative hemostasis will be the primary determining factor to decide when anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy can be restarted. Patients should not resume anticoagulation until primary hemostasis is secured. Postoperative screening coagulation tests (prothrombin time [PT], partial thromboplastin time [PTT]) should be normal, and the patient’s platelet count should be ≥ 100,000/µL. If postoperative hemostatic abnormalities exist, they should be evaluated and corrected as discussed in Chapter 14. A secondary consideration prior to restarting anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy postoperatively is the patient’s risk for thromboembolic complications. This risk is based on preoperative comorbidities (Table 15.2). The degree of intensity used when restarting anticoagulation (therapeutic versus low-dose UFH/LMWH versus no anticoagulation) will be determined by the preoperative condition necessitating chronic oral anticoagulation. No risk stratification model has yet to be validated, but the ACCP separates patients into high-risk, moderate-risk, and low-risk groups depending on the initial indication for antithrombotic therapy. Those patients requiring bridging therapy will incorporate both moderate- and high-risk groups, and thus represent the population for which this discussion is appropriate. The ACCP guidelines present class 1C recommendations for patients receiving bridging anticoagulation undergoing surgical procedures with high bleeding risk (all neurosurgical cases). These include (1) delay starting LMWH/UFH until 48 to 72 hours after surgery when hemostasis is secured, (2) administer low-dose LMWH/UFH when hemostasis is secured, or (3) completely avoid LMWH or UFH and just restart warfarin. Additional 1C recommendations state that the individual anticipated bleeding risk and degree of postoperative hemostasis should determine the time to restart UFH or LMWH rather than starting anticoagulation at a fixed period of time. Vinik et al4 have proposed an approach to resumption of anticoagulation with UFH/LMWH in patients undergoing bridging therapy (Fig. 15.1). This approach assumes that postoperative hemostasis is normal. It can be extrapolated from their proposal that in neurosurgical patients (high bleeding risk) at least 24 hours postprocedure, those with high or moderate thromboembolic risk should be started on low-dose UFH/LMWH or no anticoagulation at all.1,4 Additionally, on postoperative day 2 or 3, the UFH/LMWH dose used should be reevaluated. Patients receiving no anticoagulation who are not bleeding should be started on low-dose therapy. Patients already on low-dose anticoagulation who are without bleeding should be advanced to therapeutic dosing. Fig. 15.1 Restarting postoperative anticoagulation with unfractionated heparin (UFH) or low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is based on two variables, thromboembolic and bleeding risk. In patients with high bleeding risk and high or moderate risk of thromboembolism who have adequate hemostasis, restarting low-dose UFH/LMWH or not restarting anticoagulation should be considered at ≥ 24 hours. Additionally, an inferior vena caval filter should be considered in patients with high bleeding and thromboembolic risk. In patients with low bleeding risk and high thromboembolic risk, full-dose UFH/LMWH should be restarted at ≥ 24 hours. For those with low bleeding risk but moderate thromboembolic risk, low- or full-dose UFH/LMWH should be considered. (Data from Vinik R, Wanner N, Pendleton RC. Periprocedural antithrombotic management: a review of the literature and practical approach for the hospitalist physician. J Hosp Med 2009;4:551–559.) The primary purpose of bridging anticoagulation is to provide a window in which warfarin therapy is discontinued and the risk of thromboembolic events is minimized. As is noted in Table 15.1, at least 2 days of warfarin therapy are necessary to minimally achieve a partial anticoagulant effect (international normalized ratio [INR] ≥ 1.5). For this reason, ACCP guidelines have a 1B recommendation for restarting warfarin on (1) the evening of the day of surgery, (2) on postoperative day 1, or (3) when adequate hemostasis is achieved. Unfortunately, these recommendations are not based on the neurosurgical literature and cannot provide an easy one size fits all solution for neurosurgical patients. Many neurosurgeons may prefer to withhold full anticoagulation until they are comfortable that the patient is at minimal risk for bleeding complications, which typically is on postoperative days 3 to 4 but may be up to 1 week postsurgery. When warfarin is restarted, the patient can either receive the preoperative warfarin dose or have the home dose doubled for the first 2 days after reinitiation. Numerous studies have indicated that to achieve a therapeutic INR (2.0–3.0), 4 to 7 days of bridging anticoagulation will be necessary, with the choice of regimen differing by approximately a half day. The guidelines support the idea that once a therapeutic INR is reached, UFH/LMWH can be discontinued. Importantly, daily INR monitoring in all hospitalized patients should be done beginning the morning after initial dosing until a therapeutic INR is reached, and should be continued twice weekly thereafter.5 Many patients require antiplatelet therapy that cannot be discontinued in the perioperative period (bare metal stents within 6 weeks of placement, or within 12 months of drug-eluting stent placement). For those with high perioperative bleeding risk, antiplatelet agents are stopped 7 to 10 days prior to the procedure.6 In these patients, grade 2C recommendations per the ACCP guidelines include restarting acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) and clopidogrel ~ 24 hours after the procedure in the presence of adequate hemostasis. Again, unfortunately, these recommendations are not based on evidence from the neurosurgical literature, and many neurosurgeons may prefer to withhold antiplatelet therapy until they are comfortable that the patient is at minimal risk for bleeding complications, which typically is on postoperative days 3 to 4 but may be up to 1 week postsurgery. This decision requires a balancing of concerns about thrombotic risk versus bleeding risk and clinical significance of any potential hemorrhage. Antiplatelet bridging therapy has been proposed in patients at high risk for thromboembolism, as in patients with recent stent placement or myocardial infarction. As these patients may be “bridged” with a short-acting glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa antagonist agent (eptifibatide, tirofiban), it is reasonable to consider restarting these agents prior to oral antiplatelet therapy. It is important to note that this is an “off label” use of GPIIb/IIIa agents, and that all decisions with antiplatelet drugs should be made in conjunction with a multidisciplinary team including a cardiologist.6 There are no further guidelines concerning other agents, but these agents should not be restarted prior to achieving successful hemostasis. Once they are restarted, the ACCP guidelines recommend against the use of monitoring with platelet function assays. The use of therapeutic anticoagulation can result in a major bleeding event in up to 10 to 20% of patients.4 The decision to restart anticoagulation should incorporate evaluations of intraoperative hemostasis, preoperative thromboembolic risk based on comorbidities, and patient-related factors that may further increase the risk of bleeding (older age, need for concomitant NSAIDs or antiplatelet therapies, impaired renal function, use of spinal/epidural catheter, liver disease, or cancer).4 Only after careful consideration of all potential risks for complications can bridging anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapies be resumed. Special consideration must be given to neurosurgical patients in the postoperative period, as they are at high risk for development of potentially life-altering sequelae of both bleeding and development of thromboembolic phenomenon. Minimal literature is available for analysis in this area, and no neurosurgery specific guidelines have yet been published. It is well known that agents, such as warfarin, UFH, LMWH, clopidogrel, and ASA, increase the bleeding risk in postoperative neurosurgical patients. Major postoperative bleeding complications may lead to reoperation and possibly the development of permanent neurologic deficits. The most studied and potentially dangerous of these events is the development of an epidural hematoma. The exact incidence of postoperative symptomatic epidural hematoma formation is unknown, but is suspected to be between 0.1% and 1.0% with and without chemoprophylaxis for thromboembolism, and as high as 22% for patients on therapeutic anticoagulation for preoperative comorbidities.7,8 Review of the relevant neurosurgical literature suggests an increased relative risk for epidural hematoma formation with the use of both prophylactic and therapeutic anticoagulants, but the absolute risk of development of this complication is uncertain. That being said, the occurrence may lead to long term and permanent neurologic deficits. For this reason, numerous neurosurgical specific recommendations suggest that if anticoagulation is necessary, the use of UFH instead of LMWH is favored as it is more easily controlled, has a shorter duration of action, and is more easily reversed with protamine sulfate.9,10 Venous thromboembolic events after major spinal and intracranial procedures may also complicate recovery of full neurologic function. Patients with a high preoperative thromboembolic risk are at even greater risk for development of thromboembolism resulting from extended recumbency and limited mobility in the postoperative period. Despite these increased risks, restarting antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapy will be primarily dependent on the degree of postoperative hemostasis. Special consideration can be given to patients bridged for preoperative DVT or PE who have inadequate postoperative hemostasis. These patients should be assessed for temporary inferior vena cava (IVC) filter placement instead of immediate bridging anticoagulant therapy with UFH or LMWH.7,8 In patients who have been anticoagulated for atrial fibrillation or mechanical heart valves and who are at increased risk for postoperative development of cerebrovascular accident (stroke or TIA), individual risk-benefit analysis will be necessary to balance initiating or delaying of anticoagulation. Patients on chronic anticoagulation also present to the neurosurgeon with evidence of intracranial hemorrhage and subdural hematoma from supratherapeutic INR values with or without trauma. Wijdicks et al11 addressed in 1998 the question as to how long these patients can be taken off anticoagulation therapy. In patients considered at high thromboembolic risk (prosthetic heart valve with atrial fibrillation, or cage-ball valves), the time off of anticoagulation varied between 2 and 22 days, with no thromboembolic complications. Despite including only nine patients, this retrospective study concluded that for most patients with prosthetic heart valves, cessation of anticoagulation for 1 to 2 weeks is a sufficient amount of time to observe intracranial hemorrhage, clip or coil aneurysms, or evacuate hematoma without an increased risk for development of thromboembolism.11 Patients undergoing elective spine surgery, intervention for traumatic head injury or neoplasm, or patients with intracranial hemorrhage without surgical intervention necessitate particular attention to individualized risk–benefit analysis of a postoperative thromboembolic event and bleeding. These risks must be incorporated into the decision-making process once a patient has achieved adequate hemostasis for reinitiation of anticoagulation. Ultimately, bridging anticoagulation cannot be reinstituted until postoperative bleeding is well controlled. C.K. is a 45-year-old woman who presents to the emergency department (ED) with acute-onset right-sided chest pain. In the past 1 month, the patient has undergone left and right total hip arthroplasty for pathological fractures resulting from lytic bone lesions suspected to be secondary to multiple myeloma. She has been continued on prophylactic doses of Lovenox since after her first surgical intervention. During evaluation of her chest pain, a computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the chest reveals bilateral, right greater than left, pulmonary emboli. She subsequently has her Lovenox dose increased to therapeutic, twice daily dosing. One week later, the patient again presents to the ED after developing a progressively worsening, diffuse headache, confusion, and slurred speech. A CT of the head indicates an acute intracranial hemorrhage, and the patient undergoes emergent neurosurgical intervention after the anticoagulant effect was emergently reversed. These questions arise: When should anticoagulation be restarted? In the immediate postoperative period, which anticoagulant should be used? The following approach should be considered: • This patient has a high potential risk for a clinically significant hemorrhage if anticoagulation is restarted too soon but also has a recent DVT and PE diagnosis. A reasonable strategy would be to place a temporary IVC filter and postpone anticoagulant therapy for several weeks, with the filter removal done after therapeutic anticoagulation is achieved. • In addition to the IVC filter, it may be appropriate to start low-dose heparin therapy at 24 to 48 hours postoperative if the patient’s CT head scan and clinical exam are stable. On postoperative days 2 to 5, the patient should be reassessed to determine if progression of therapy to either low-dose (if not previously started) or high-dose (if already on low-dose) heparin therapy. • Unfractionated heparin (rather than LMWH) is considered the more appropriate agent for bridging therapy in the neurosurgical patient, as it enables better control of the anticoagulant effect. • The IVC filter can be removed after the patient has resumed full anticoagulation. H.B. is a 72-year-old man with a past medical history significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, stroke, and coronary artery disease, who was initially diagnosed with a stage IIa diffuse large B-cell lymphoma approximately 10 years prior to presentation. The patient received chemotherapy, and was in complete remission after treatment. Eleven months prior to presentation, the patient underwent coronary catheterization, and received a drug-eluting stent to the left anterior descending artery. Since this intervention, the patient has been maintained on clopidogrel. On presentation at a hospital today, the patient’s family reports altered mental status and the patient describes a diffuse, dull headache. CT imaging is significant in showing two lesions in the right temporal and parietal areas suspicious for central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma. The oncology team requests biopsy and plans to consult cardiology for appropriate options for stopping clopidogrel. Assuming cardiology believes that it is appropriate to discontinue clopidogrel for this procedure, and that there were no significant surgical complications, after how many days preoperative should the clopidogrel be stopped and when can it be restarted after the operation? The following approach should be considered: • Clopidogrel should be stopped 5 to 7 days before the operation. • Assuming adequate hemostasis, clopidogrel may be restarted at 48 to 96 hours status-postprocedure if the CT head scan and clinical exam are stable. • All intracranial and spine surgeries are considered high bleeding risk procedures. • No specific evidence-based guidelines exist for postoperative reinitiation of bridging anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy in neurosurgical patients. • Patients need to be evaluated on an individual basis for adequate hemostasis and thromboembolic complication risk in the postoperative setting prior to restarting all anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapies. • The following issues pertain to resumption of anticoagulation in the postoperative setting:

Postoperative Strategies for Resumption of Anticoagulants and Antiplatelet Agents in Neurosurgical Patients

Classes of Agents

Postoperative Resumption of Anticoagulant and Antiplatelet Therapy

Neurosurgery-Specific Issues

Case Example 1

Case Example 2

All guidelines to date regarding the reinitiation of postoperative anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy are based on grade 1B/C and 2C recommendations.

All guidelines to date regarding the reinitiation of postoperative anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy are based on grade 1B/C and 2C recommendations.

Preoperative bleeding risk and postoperative hemostasis dictate the timing for starting or restarting anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy.

Preoperative bleeding risk and postoperative hemostasis dictate the timing for starting or restarting anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy.

Preoperative risk of thromboembolism governs the degree of aggression in the dosing of heparin/LMWH postoperatively.

Preoperative risk of thromboembolism governs the degree of aggression in the dosing of heparin/LMWH postoperatively.

If postoperative hemostasis is adequate, UFH/LMWH can be restarted at 48 to 96 hours postprocedure depending on the diagnosis, clinical exam, and CT findings.

If postoperative hemostasis is adequate, UFH/LMWH can be restarted at 48 to 96 hours postprocedure depending on the diagnosis, clinical exam, and CT findings.

If postoperative hemostasis is adequate, warfarin can be restarted at 48 to 96 hours postprocedure depending upon the diagnosis, clinical exam, and CT findings.

If postoperative hemostasis is adequate, warfarin can be restarted at 48 to 96 hours postprocedure depending upon the diagnosis, clinical exam, and CT findings.

If postoperative hemostasis is adequate, ASA and clopidogrel can be restarted at 48 to 96 hours postprocedure depending on the diagnosis, clinical exam, and CT findings.

If postoperative hemostasis is adequate, ASA and clopidogrel can be restarted at 48 to 96 hours postprocedure depending on the diagnosis, clinical exam, and CT findings.

In patients on ADP receptor inhibitors, GPIIa/IIIb inhibitors, and adenosine reuptake inhibitors, consultation with a cardiologist is recommended prior to restarting these medications.

In patients on ADP receptor inhibitors, GPIIa/IIIb inhibitors, and adenosine reuptake inhibitors, consultation with a cardiologist is recommended prior to restarting these medications.

Consider the use of a temporary IVC filter for patients who are at high risk of developing or already have a DVT/PE and have a high risk of bleeding.

Consider the use of a temporary IVC filter for patients who are at high risk of developing or already have a DVT/PE and have a high risk of bleeding.

Postoperative Strategies for Resumption of Anticoagulants and Antiplatelet Agents in Neurosurgical Patients

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree