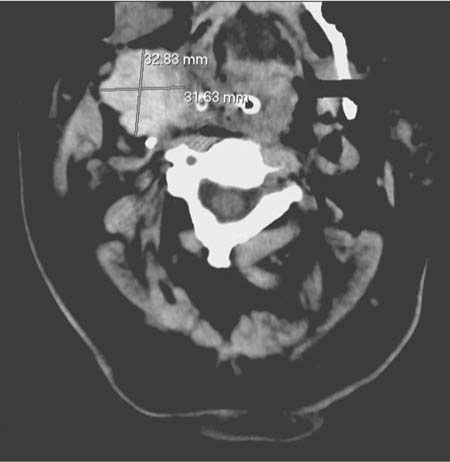

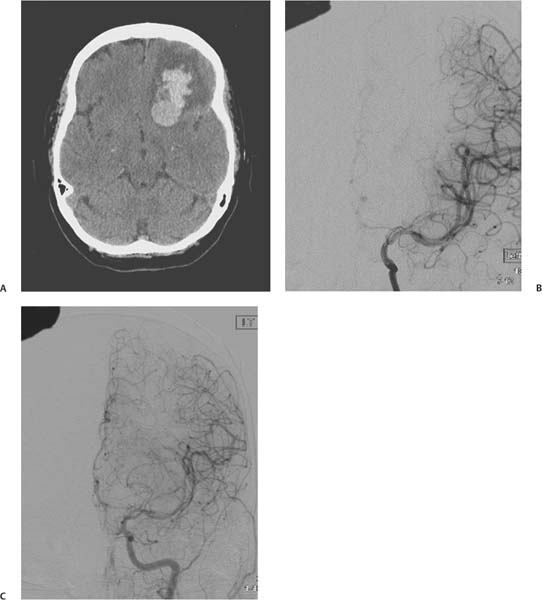

Chapter 19 Postoperative observation and management of postprocedural complications is a crucial role for neurocritical care. Although most neurosurgical textbooks emphasize surgical technique, little is often written addressing postprocedural complications. Treatment remains largely anecdotal based on variably sized cohorts. In this chapter we attempt to synthesize the available knowledge on the complication rates and management of the most common neurovascular procedures. Carotid endarterectomy (CEA) for primary and secondary prevention of stroke is one of the most common surgical procedures performed in the United States.1 Epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that the long-term benefit of surgery can be negated by excessive postoperative morbidity.2,3 Meticulous surgical techniques and careful patient selection has been emphasized; however, despite this there still remains significant information on CEA complications. The most common complication post-CEA is the development of a cranial nerve deficit. Individual cranial nerve deficits occur in 6 to 17% of procedures.4 The most common nerves involved include the facial, recurrent and superior laryngeal, hypoglossal, marginal mandibular, and the glossopharyngeal. The North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) reported a 7.6% incidence of cranial nerve deficits.2 The wide variation in reported deficits, however, probably represents the degree of scrutiny involved when looking for a deficit. When laryngoscopy is included, complication rates approach 16%.5 Fortunately, most cranial nerve deficits are temporary and resolve in 3 to 6 months. Most are not considered serious complications and are due to traction and compression injuries and not transection of the nerves. One potentially serious complication can occur if bilateral recurrent laryngeal or hypoglossal nerves are damaged during bilateral procedures. This can seriously impair respiration and airway control leading to a chronic severe cough and aspiration.4,5 Laryngoscopic examination of these nerves prior to staged bilateral operations should be performed to ensure the integrity and function of the involved muscles and nerves.5 Wound hematomas have ben estimated to occur in ~5.5% of procedures. Most are small and nonsignificant representing oozing from the surgical site, which can be aggravated by antiplatelet agents and heparinization. Rupture of the arterial suture site is rare and is usually fatal. Bleeding requiring reoperation has been reported to occur in 0.7 to 2.5% of cases.6 Reoperation for examination should be considered for any obvious hematoma. More urgent evacuation is needed for rapidly expanding hematomas that can compromise airways. Emergent bedside evacuation is recommended in this clinical situation even prior to endotracheal intubation.1 Figure 19.1 shows an example of right neck hematoma next to the CEA site. This patient required an emergent tracheostomy and control of bleeding. Fig. 19.1 Right neck hematoma after an elective right carotid endarterectomy. Operative stroke is the measure by which CEA is evaluated. Several clinical series evaluating operative stroke during CEA were performed in the 1970s and 1980s. Most were from academic institutions using cerebral monitoring and shunting techniques. The reported stroke rates ranged between 1.6 to 6.5%.1 In general stroke rates need to be ≤3% in asymptomatic patients and ≤6% for symptomatic patients for long-term benefit from the procedure.7 Questions have been raised whether low-volume centers can meet these criteria.8 Stroke rates are reported higher with contralateral carotid occlusion, ulcerated plaques, and patients with previous strokes.1,4 Continuous transcranial Doppler ultrasound has revealed that 30% of CEAs will have evidence for distal emboli during the procedure. Most are considered gaseous emboli and are of little significance; however, the appearance and timing of these emboli have provided clues as to when distal thrombotic emboli may occur.9 Operative strokes are believed to occur during prepping of the site, dissection and manipulation of the carotid, and during cross clamping. Cerebral monitoring, arterial shunts, and other protective devices have all been developed to decrease the incidence of operative strokes.9 About half of all strokes occur postoperatively. The mechanism is presumably secondary to emboli from an acute carotid occlusion or microembolization from the denuded endothelium of the surgical site. Cerebral hypoperfusion can occur but is believed to occur less frequently than distal emboli.9 Antiplatelet agents are used almost universally by surgeons before, during, and after the procedure. Heparin is similarly used during surgery, but there are variations in practice as to whether anticoagulation is continued, discontinued, or reversed after surgery.1,9,10 The decision to consider reexploration of the site can be quite difficult because many postoperative deficits may be transient and a reoperation could potentially worsen the situation. An urgent reoperation is encouraged when a patient awakens with a severe neurologic deficit.9 Carotid artery disease is a marker for coronary artery disease. Myocardial infarctions are common post CEA occurring in 2 to 3% of patients and accounting for 40 to 50% of all late deaths.9 Patients should have postoperative electrocardiographic (ECG) monitoring and be followed closely for signs of myocardial ischemia. A low threshold should be given to send cardiac biomarkers for suspected cardiac ischemia. As our understanding of cerebral autoregulation has improved, the occurrence of postoperative hyperperfusion has become rare. Nevertheless, it remains part of the Differential diagnosis of new neurologic change in the postoperative period. Figure 19.2 shows an example of a left frontal intracranial hemorrhage that developed after an internal carotid artery stenting procedure. The repeat angiogram clearly shows hyperperfusion of the left anterior cerebral artery. This complication can be avoided by carefully controlling the blood pressure after revascularization. Anticoagulants and antiplatelet therapies are closely monitored as these can play a role in hemorrhagic conversion of the hyperperfusion areas of the brain. Postoperative management of patients undergoing a CEA poses some specific challenges. Hemodynamic instability is common and includes persistent hypertension, bradycardia and hypotension, and normal perfusion pressure breakthrough. Careful blood pressure, fluid and electrolyte management is necessary to avoid large fluctuations in hemodynamics. Postoperative patients are typically followed in a postanesthesia care unit for 2 to 3 hours after CEA. A slow emergence from anesthesia may be beneficial in moderating blood pressure changes postoperatively.11 Analgesia may need to be limited to facilitate a neurologic exam. Patients may arrive in the intensive care unit (ICU) intubated. Care should be taken to inspect the surgical site for bleeding or swelling. Any deviation of the airway should prompt a return to the operating room. A neurologic assessment should focus on focal deficits and/or subtle cranial nerve deficits. A 12-lead ECG should be performed along with a thorough cardiac assessment. Most patients are admitted to the ICU overnight. Swallowing and orthostasis should be evaluated prior to dismissal from the ICU.11,12 Fig. 19.2 (A) Admission CT scan showing left frontal bleeding. (B) Baseline left internal carotid angiogram during stent procedure with limited left anterior cerebral artery flow. (C) Left anterior cerebral artery flow at the time of admission 5 days after an elective left carotid stent procedure. Postoperative hypertension is common, occurring in 50 to 60% of patients. Persistent hypertension is associated with worse outcomes and correlates with severe preoperative hypertension.13 As a result, some experts recommend delaying elective surgery until preoperative hypertension is controlled.1 Hypertension and hypotension are prevalent after carotid reconstruction and severe blood pressure fluctuations can occur after bilateral CEA.14 Hypertension is postulated to be mediated through damage to the sinus nerve of Hering. Under these circumstances damage to this nerve may be misinterpreted through the normal neurologic reflex arc mediated at the brainstem as a sustained reduction in blood pressure. Thus, compensatory reflex mechanisms designed to induce hypertension are initiated. Postoperative bradycardia and hypotension can also occur when the sinus nerve function is preserved. Under these circumstances carotid sinus transmural pressure is increased post CEA. This is interpreted as sustained hypertension, which initiates mechanisms to lower blood pressure.1 This hypothesis has been supported by several reports of successful treatment of postoperative hypertension with local anesthesia to the sinus nerve.1,15,16 Towne, however, could not reproduce these findings with transection of the nerve.17 Wade et al suggested that the effect of the sinus nerve decreased significantly with age and was severely attenuated in the elderly, a group commonly treated with CEA.18 Finally, Ransen et al noted that hypovolemia was the major contributing factor to postoperative hypotension. Similarly, bradycardia was a problem only in the setting of hypovolemia. In most instances this can be easily corrected.19 The treatment of post-CEA hypertension is somewhat controversial. Some authors have argued that transient postoperative hypertension should not be aggressively treated to avoid significant drops in blood pressure, which could potentially be harmful. Postoperative hypertension is argued to be in reaction to and not the cause of neurologic deficits in many instances.20 It is generally agreed, however, that severe hypertension should be treated and that significant fluctuations in blood pressure should be avoided. The most feared consequence of uncontrolled hypertension is normal perfusion pressure breakthrough with subsequent intracerebral hemorrhage. Cerebral autoregulation is believed to be downregulated in the ipsilateral hemisphere in severe carotid stenosis due to a persistent decrease in perfusion pressure. Once the stenosis is removed the downregulated hemisphere is subjected to relative high-perfusion pressures even in the setting of normal blood pressure. Sundt et al demonstrated a significant increase in cerebral blood flow ipsilateral to a CEA in the setting of normal blood pressure.21 Even with large increases in blood flow intracerebral hemorrhage occurs in < 1% of CEAs.1

Postprocedure Complications and Complication Avoidance

Carotid Endarterectomy

Carotid Endarterectomy

Complications

Complications

Cranial Nerve Deficits

Neck Hematomas

Neck Hematomas

Ischemic Stroke

Ischemic Stroke

Myocardial Infarction

Postoperative Hyperperfusion

Postoperative Management

Postoperative Management

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree