Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Carla Smith Stover

Steven Berkowitz

Steven Marans

Joan Kaufman

Introduction

Kevin is a 5-year-old boy whose father murdered his mother in a domestic dispute while he was at school. His father was arrested the same day and Kevin initially went to stay with his paternal grandparents who frequently provided care for him while his parents worked. That evening, Kevin sat for several hours on the family couch not reacting to the chaos and upset around him. He was quiet and appeared distant and withdrawn. He refused to speak to anyone and stared off into space. The following day, he was removed from his paternal grandparents’ care and placed in a foster home because his grandfather posted bail for his father. Child protective services felt Kevin was at risk due to the grandfather’s actions in support of Kevin’s father. Kevin’s relatives then began a custody battle over who would serve as his guardian. Kevin remained in foster care for several months while protective services assessed which family member was most appropriate. A custody and placement evaluation was conducted over the subsequent months and it was a full year until the guardianship issue was resolved.

This case illustrates several important factors that can increase the likelihood of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) developing following a traumatic event: 1) Kevin evidenced dissociation immediately following the event. Children are more likely to develop severe PTSD symptomatology if they display dissociative symptoms following the trauma (1); 2) Kevin experienced additional stress in the aftermath of the initial loss of his mother by being dislocated to a foster home. He not only lost his mother, but his home with all its familiar surroundings, and several other close family supports. PTSD is more likely when there are additional post event stressors such as dislocation, and loss or separation from significant caregivers (2,3); and 3) Kevin’s other relatives, with whom he had a previous close relationship, were not as available to provide appropriate support given their own grief and subsequent custody battle over his guardianship. If caregivers are distressed and distracted by other issues, children tend to have more difficulties, as caregivers’ own psychological problems render them less capable of providing for the children’s needs (4).

Intrafamilial violence is the most common precipitant of PTSD in children and adolescents (5,6,7), yet PTSD can emerge as a consequence of exposure to a wide range of traumas, including terrorism, war, natural disasters, automobile accidents,

and community violence. The precipitant may constitute an isolated incident, or as in the case of Kevin, a chronic stressor. Over the past two decades there has been a burgeoning of research in the area of PTSD, and significant advances in its assessment and treatment in children and adolescents.

and community violence. The precipitant may constitute an isolated incident, or as in the case of Kevin, a chronic stressor. Over the past two decades there has been a burgeoning of research in the area of PTSD, and significant advances in its assessment and treatment in children and adolescents.

Definitions

Formal diagnostic criteria for PTSD were not introduced until 1980, with the publication of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition (DSM-III) (8). In 1987, in response to new data suggesting that symptoms and distress were common after severe trauma (9), minimum duration criteria requiring symptoms to be present for at least 30 days were added to the diagnosis of PTSD (10). The minimum duration criteria, however, created a diagnostic dilemma, such that the diagnosis of adjustment disorder was the only possible diagnosis for stress-related symptomatology in the first month after a traumatic event (9). This deficit was addressed with the inclusion of the diagnosis Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) in the DSM-IV (11).

The diagnostic criteria for ASD and PTSD are delineated in Table 5.15.2.1. To receive a diagnosis of ASD, a child must exhibit symptoms for a minimum of 2 days and a maximum of 4 weeks post trauma. If symptoms persist or occur after the 4-week time limit for ASD, then the diagnosis of PTSD is given. An immediate diagnosis of ASD is not required for a child to later be diagnosed with PTSD, and PTSD can be diagnosed with acute onset, or delayed onset, if symptoms emerge 6 or more months after the event.

Criterion A for ASD and PTSD are exactly the same. The diagnosis of either disorder requires the experience of extreme stress and an intense response to the event. In practice, however, it is often quite difficult to elicit information about the child’s response to a given trauma.

The diagnoses of ASD and PTSD require the presence of reexperiencing, avoidance and/or dissociation, and hyperarousal symptoms. ASD and PTSD differ in the priority given to the different categories of symptoms, with three or more dissociative symptoms required for the diagnosis of ASD, and fewer if any dissociative symptoms necessary for the diagnosis of PTSD.

The DSM allows for developmental differences in the presentation of symptoms in children. Recurrent thoughts may be evident in children, not only through verbal reports, but also in play themes. A child who underwent a stressful medical procedure may enact doctor and patient themes repeatedly, a child who was physically abused may depict a parent character degrading and harming a child character, and a child who was sexually abused may play out scenes with sexually explicit material. In addition, in children, nightmares need not specifically be related to the trauma to count as a reexperiencing symptom; any frightening dreams with onset after the trauma can count toward the diagnosis of PTSD. Also, instead of reliving the trauma mentally, trauma-specific reenactment can count toward the diagnosis of PTSD in children. In sexually abused children this frequently takes the form of initiating sexual advances toward other children. Additional information about diagnosing PTSD in children, and developmental considerations in diagnosing very young children, are discussed later in the chapter in the Diagnosis and Assessment section.

Epidemiology

The National Comorbidity Study is the most comprehensive epidemiological survey of psychiatric disorders in the United States. Just under 6,000 individuals aged 15–54 participated in the study. The estimated prevalence of PTSD was 7.8% overall, and 10.4% for women, double the rate observed in men. Rape and combat were the most likely events to be associated with PTSD in the National Comorbidity Study (12).

PTSD rates are believed to be similar, if not higher, in children and adolescents (13). Several epidemiological studies estimate trauma exposure rates in children to be between 25% and 45% (14,15). Of children with a history of traumatic event exposure, rates of PTSD range from 5% to 45% (15,16,17), with higher rates reported in low income high-risk subjects, and lower rates reported in pediatric emergency room samples. Within juvenile cohorts, as discussed earlier, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and intrafamilial violence are the most common precipitants of PTSD (5,6,7).

Neurobiology

Preclinical studies of the effects of stress provide a valuable heuristic in understanding the pathophysiology of PTSD in adults (18,19), with many of the biological alterations associated with early stress in preclinical studies reported in adults with PTSD. For example, one of the best replicated findings in adults with PTSD is reduction in hippocampal volume (20,21,22,23,24,25,26). There has been some suggestion that reduced hippocampal volume represents a preexisting, inherent vulnerability factor, rather than a consequence of trauma exposure, given one study found combat exposed twins with PTSD and their unexposed cotwins had smaller hippocampal volumes than combat-exposed twins without PTSD and their unexposed cotwins (27). This interpretation has to be accepted with caution, however, as the combat-exposed veterans who developed PTSD and their unexposed cotwins were more likely to have had a history of childhood physical and/or sexual abuse, suggesting the potential importance of early developmental insults on later hippocampal structure.

Preclinical studies of the effects of stress suggest a minimum of three mechanisms through which hippocampal atrophy may result: neuronal atrophy, neurotoxicity, and disruption of neurogenesis. In animals, 3 weeks of exposure to stress and/or stress levels of glucocorticoids can cause neuronal atrophy in the CA3 region of the hippocampus (28,29). At this level, glucocorticoids produce a reversible decrease in number of apical dendritic branch points and length of apical dendrites of sufficient magnitude to impair hippocampal-dependent cognitive processes (28). More sustained stress and/or glucocorticoid exposure can lead to neurotoxicity— actual permanent loss of hippocampal neurons through binding of glutamate to N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. Rats exposed to high concentrations of glucocorticoids for approximately 12 hours per day for 3 months experience a 20% loss of neurons specific to the CA3 region of the hippocampus (30). Evidence of stress-induced neurotoxicity of cells in this region has been reported in nonhuman primates as well (31,32). Reductions in hippocampal volume may also be affected by decreases in neurogenesis, which results from decreased expression of Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) caused by elevated glucocorticoids (33). The granule cells in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus continue to proliferate into adulthood, and neurogenesis in this region is markedly reduced by stress.

Contrary to expectations derived from preclinical studies of the effects of early stress on hippocampus structure (34), and imaging studies of adults (35), multiple pediatric studies have failed to detect hippocampal atrophy in children with PTSD (36,37,38,39). While some clinical studies suggest the failure to detect hippocampal atrophy may be due to the low rate of recurrent depressive illness or comorbid alcohol problems in pediatric samples (40,41), there are emerging findings that suggest multiple developmental factors may be relevant in

understanding the absence of hippocampal findings in children and adolescents with PTSD. For example, there are age-dependent changes in sensitivity to NMDA receptor blockade, as in preclinical studies of neurotoxicity in corticolimbic regions, cell death has been reported to be minimal or absent during prepuberty, only reaching its peak in early adulthood (42).

understanding the absence of hippocampal findings in children and adolescents with PTSD. For example, there are age-dependent changes in sensitivity to NMDA receptor blockade, as in preclinical studies of neurotoxicity in corticolimbic regions, cell death has been reported to be minimal or absent during prepuberty, only reaching its peak in early adulthood (42).

TABLE 5.15.2.1 DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR ASD AND PTSD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Instead of hippocampal atrophy, children and adolescents with PTSD have been found to have reduced medial and posterior corpus callosum areas in two independent investigations (36,38). This is a finding that has likewise been reported in psychiatric inpatients with a history of maltreatment when compared to psychiatric and healthy controls without a history of early childhood trauma (43).

To the best of our knowledge, there is only one published structural MRI study in prepubescent nonhuman primates subjected to early stress (44). Most preclinical studies of the effects of early stress have examined the impact of early stress on the neurobiology of adult animals. Consistent with the child clinical studies, prepubescent primates subjected to early maternal deprivation failed to show evidence of hippocampal atrophy, and instead had reductions in the medial and posterior portions of the corpus callosum.

The medial and posterior portions of the corpus callosum contain interhemispheric projections from the auditory cortices, posterior cingulate, insula, and somatosensory and visual cortices to a lesser extent. They also include connections from the inferior parietal lobe to the contralateral inferior parietal lobe, superior temporal sulcus, cingulate, retrosplenial cortex, and parahippocampal gyrus (45). Several of the regions with interhemispheric projections through the medial and posterior portions of the corpus callosum have connections with prefrontal cortical areas, and are involved in circuits that mediate the processing of emotional stimuli and various memory functions— core disturbances associated with PTSD.

Given findings in juvenile cohorts in the corpus callosum— the primary white matter tract in the brain— we utilized diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) in a cohort of maltreated children with PTSD. DTI is a relatively new application of MRI technology that measures the extent and direction of diffusion of water in the brain, and can be used to assess the integrity of white matter tracts (see Peterson, 2.4.1). When compared to demographically matched controls, maltreated children with PTSD had reduced fractional anisotropy (FA) in the medial and posterior region of the corpus callosum (46). FA is greatest in axons, and increases with myelination, suggesting the possibility of myelination alterations in association with early traumatic life events.

It is probably premature to conclude that alterations in hippocampal structure are not evident in preadolescents. MRI methodology may just be too crude to identify structural hippocampal changes. In order to better understand the neurobiological effects of stress early in development, additional preclinical studies are needed that systematically examine the effects of stress on prepubertal animals and across development using refined research methodologies to detect subtle changes in hippocampus structure (e.g., cell proliferation and gene expression, to complement MRI findings). Emerging findings from adult studies implicate a range of neuroanatomical structures that are likely relevant in the pathophysiology of PTSD, and additional work in this area in juvenile samples will also help to elucidate structures and circuits relevant early in development.

As was discussed extensively in the previous chapter (see Kaufman, 5.15.1), the negative neurobiological sequelae associated with a history of early trauma are not inevitable. There is a host of environmental and genetic factors that can modify the impact of early trauma. Some of the factors most relevant in modifying the emergence and course of PTSD are delineated in the Course and Prognosis section of this chapter.

Diagnosis and Assessment

Multiple Informants and the Assessment of Trauma

In the area of child psychopathology assessment, extensive attention has been paid to the finding that independent raters (parents, teachers, children) often provide discrepant yet important information about children’s psychiatric symptomatology (47). Emerging findings suggest the same is true in assessing children’s trauma experiences (48,49).

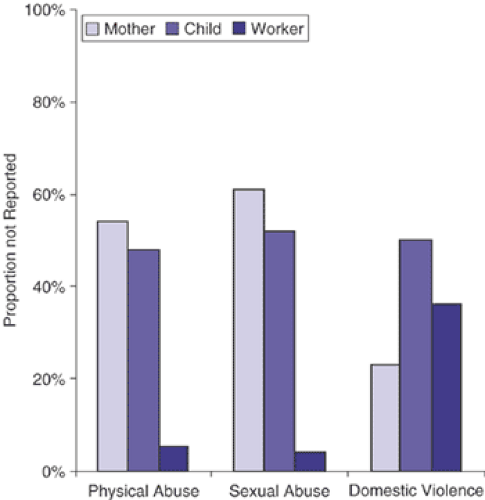

Multiple informants and multiple measures appear necessary to accurately assess children’s trauma histories, a first and critical step in the assessment of PTSD. For example, in one recent study (50), child-, parent-, and protective-services data were used to assess children’s traumatic experiences. Each of the data sources missed a number of traumas identified by the other methods. All three sources of information, however, were able to be reliably integrated to provide a “best estimate” of children’s maltreatment experiences. Figure 5.15.2.1 shows the proportion of traumas experienced by the children identified after all sources of data were reviewed that were not reported by each informant alone. Substantiated incidents of physical and sexual abuse documented in protective service records were denied by parents and children approximately 50% of the time when queried directly about these types of experiences. Of the various types of traumas, parents were most likely to report incidents of domestic violence. In addition, parents occasionally reported incidents of physical and sexual abuse that occurred in the past when the family was living in another state and that their workers did not know about. Utilizing only parent and child interview data, without access to the protective service record, 40% of the children with a history of sexual abuse, 30% of the children with a history of physical abuse, and 16% of the children with a history of witnessing domestic violence would not have been identified. In these cases, PTSD symptoms would not ordinarily be surveyed, and the diagnosis of PTSD would have been missed.

The data described above highlight the importance of clinicians obtaining information from multiple sources (child protective services, children, parents) when making psychiatric diagnoses and delineating treatment plans for maltreated children. Comprehensive multi-informant assessment will help to assure proper diagnoses and optimal selection of appropriate clinical interventions, including trauma-focused psychotherapies. Working collaboratively with parents and/or protective service workers is essential in the care of these children.

As reviewed elsewhere (51), there are several good measures of trauma exposure to help clinicians determine if a child has experienced a Criterion A trauma. The Traumatic Events Screening Inventory (TESI) (52) and Violence Exposure Scales (VEX-R) (53) assess a wide variety of childhood traumas, and both have caregiver and child-report versions. Most of the standard semistructured and structured child psychiatric diagnostic interviews also include a survey of a variety of criterion A traumas. Reliable, more detailed measures of domestic violence can be obtained with the Revised Conflict Tactics

Scale (CTS2) (54) or the Partner Violence Inventory (PVI) (55), and the Child Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) (56) provides an excellent assessment of a range of maltreatment experiences. Reliable methods have also been developed to extract and rate severity of maltreatment experiences from case records (57), and to integrate trauma data from multiple informants (48).

Scale (CTS2) (54) or the Partner Violence Inventory (PVI) (55), and the Child Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) (56) provides an excellent assessment of a range of maltreatment experiences. Reliable methods have also been developed to extract and rate severity of maltreatment experiences from case records (57), and to integrate trauma data from multiple informants (48).

Symptom Assessment

In our clinical and research practice, we aim to have trauma history data from multiple informants prior to assessing psychiatric symptomatology in children. We then query them about various trauma experiences. If children deny a trauma we know they have experienced via other sources, we consider that evidence of “avoidance.” We then let them know what we learned about from the other source, let them know that we are not going to ask them too much about those experiences, but want to know if they have any problems a lot kids experience who have been through the type of things they have. We then query them regarding the presence of PTSD symptoms. If children are particularly reticent to talk, we begin by asking the more benign hyperarousal items (sleep difficulties, concentration problems, irritability), progress to ask about the avoidance/numbing symptoms, and then query about the more stressful reexperiencing items.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree