Childhood obesity is not a benign condition; it is associated with premature death and adult disease. Franks and colleagues (6) studied 4,857 Native American, non-diabetic children (mean age 11.3 years at baseline) to determine which of four risk factors—BMI, high cholesterol, blood pressure, or glucose tolerance—best predicted early mortality from endogenous causes (in other words, by disease or self-inflicted death instead of accidents or homicide). The study followed the children for more than 20 years, during which period there were 559 deaths, of which 166 were suitable for the analysis. Of the factors studied, high BMI alone predicted premature death by endogenous causes; glucose intolerance, high blood pressure, and hypercholesterolemia alone failed to significantly predict premature death. Furthermore, obesity in youth still strongly predicted premature death even after a statistical adjustment to control for development of type 2 diabetes in adulthood. The most obese children were more than twice as likely to die prematurely (6). Other work by Franks and colleagues (7) shows that obesity in young children is a much stronger predictor of later type 2 diabetes than any other conventional metabolic or cardiovascular risk factor.

This chapter presents the case for prevention, a discussion of various types of prevention, and selected strategies recommended for the prevention of childhood obesity in a number of settings, with particular emphasis on the earliest period of child development, when the primary influencers on the child are the parents and family. Throughout the chapter we describe what might happen in a variety of settings, and what society might look like, if prevention of childhood obesity were treated as a national priority. We have tried to emphasize how we might better support parents and families and indicate what specific research findings might guide and foster the development of effective strategies to prevent childhood obesity.

The Case for Prevention As a National Priority

The CDC estimates that there are approximately 12.5 million obese children in the US today (8). Once established, childhood obesity often persists into adulthood (9, 10) and is notoriously difficult to treat (see Chapter 20). Obese children face many adverse psychosocial and health risks (11). Obese children are targets of social discrimination and this can cause low self-esteem and poor performance in school (12). In addition to negative social consequences and early mortality (13), obese children suffer from higher rates of illness which is both costly and preventable (14). The growing prevalence of childhood obesity is fueling an alarming increase in type 2 diabetes and in risk factors for heart disease which now occur during childhood and early adulthood (10, 15–18).

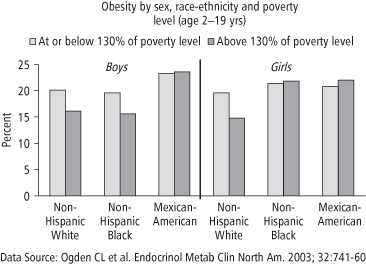

Obesity prevalence and its toll in disease and suffering are distributed disproportionately among poorer and minority members of the US population, although the data for children differ by sex (see Figure 27-2).

Figure 27-2 Data illustrating the effects of socioeconomic status and ethnicity on prevalence of obesity prevalence, by sex

A disproportionate number of obese children are Native American, African American, Hispanic, or Asian/Pacific Islanders (10, 19–23). Obesity among immigrant children and adolescents is an increasing problem (24) although prevalence varies substantially by ethnicity and generational status (24). Obesity is also rising at disproportionately high rates among rural residents, including children (25, 26). State data on obesity prevalence among low-income, preschool-aged children shows that the prevalence was 12.4% in 1998 but rose to 14.6% in 2008. (27) These data include prevalence data for pre-schoolers from major Indian reservations and show that prevalence ranged from a low of 12% in children from the Chickasaw Nation (Oklahoma) to 20.9% in the Inter Tribal Council of Arizona (27).

The Diseases and Costs Associated with Childhood Obesity

US healthcare expenditures, currently estimated at 16% of national GDP (28), will likely reach $4 trillion and represent 20% of GDP by 2015 (29). Much of the dramatic increase in healthcare costs is driven by the growing prevalence of obesity-related illness and disability, especially medical spending for the treatment of diabetes, dyslipidemia, and heart disease (30). Medicare and Medicaid populations suffer higher rates of obesity than the national average; consequently, the percentage of medical expenditures attributable to obesity in these populations is conservatively estimated2 at 6.8% of healthcare expenditures for Medicare and 10.6% for Medicaid, as compared to the 5.7% estimated for the nation as a whole (31).

Prevention of obesity is considered to be cost-effective when compared to the cost of treating obesity or its health consequences, a cost that was estimated at $117 billion annually in 2001 (32) but is rising rapidly as costly bariatric surgical procedures (33, 34) and other treatments become more common (see Chapter 19). Promising studies of the offspring of severely obese mothers who underwent bariatric surgery show a markedly lower obesity prevalence in those children as compared to children born to the same mothers prior to surgery (35–37). Although these outcomes will have to be replicated by other groups, this benefit of childhood obesity prevention in the offspring of weight-reduced severely obese mothers may, over the long term, offset some of the cost of treating women (and possibly teens) of childbearing potential.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) has estimated the national costs for illness related to childhood obesity per se to be $14 billion (14). The IOM has also described the upsurge in type 2 diabetes as a “major public health crisis” among American Indian and Alaskan Native teens. One analysis (15) of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data (1999–2002) collected on 4,370 adolescents aged 12–19 years projected that more than 39,000 US adolescents are now afflicted with diabetes, and another 2.7 million have impaired fasting glucose levels (pre-diabetes). Another analysis of NHANES data (1999–2000) revealed 17.8% with impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) among obese teens as compared to only 7% among normal-weight teens (18). In addition to type 2 diabetes, other so-called “adult” diseases such as sleep apnea, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hepatic steatosis are becoming more commonplace among the obese pediatric population (38)—a circumstance unheard of 30 years ago, before the upsurge in childhood obesity prevalence.

The Link between Childhood and Adult Obesity

Obesity in childhood persists into adulthood (9, 10). Whitaker (9) studied height and weight records of 854 children born between 1965 and 1971 in a health maintenance organization in Washington state. This study demonstrated that obesity in children “tracks” into young adulthood, meaning that 80% of the obese teens (15 years old or older) were still categorized as obese at 21–29 years of age. Among older children, obesity is an increasingly important predictor of adult obesity: obese 15–17 year olds faced a 17-fold higher risk of adult obesity. Among children younger than 10 years, the presence of obesity in one parent doubles the risk that obese children will remain obese into adulthood, but the risk is substantially higher if both parents are obese (9). In girls, obesity in childhood raises the risk of obesity persisting into young adulthood: as compared to normal-weight girls, the risk increased by 11-fold in obese 9–11 year olds to 30 times greater risk in older obese teens (10).

Despite the pervasiveness and persistence of obesity as a serious and costly public health threat, the evidence base on prevention of childhood obesity is distressingly thin (14, 39). Building the evidence base and implementing effective programs and strategies is the primary challenge before us. As a nation, we must take into account that childhood obesity occurs in racially, ethnically, economically, and culturally diverse contexts. Action is needed on a multitude of levels, ranging from the individual, family, and community levels to the local, state, and federal political levels (14, 39). We must engage industries ranging from the food and restaurant to the healthcare, insurance, major media, and entertainment industries, in order to shift societal values and norms toward the widespread adoption of a healthy lifestyle that encourages and maintains energy balance through healthy eating, portion control, and increased physical activity (14, 39).

The Complexity of Prevention

For researchers seeking to identify promising strategies to prevent childhood obesity, the complex nature of obesity etiology has presented a formidable challenge. The human body conforms to the laws of thermodynamics, and weight is maintained if, on average, energy consumed balances or equals energy expended. The development of obesity results from a failure to maintain energy (or calorie) balance, but the path to obesity is complex. It is often the result of an interaction among insufficient physical activity, consumption of excess calories, and genetic predisposition, within the context of a whole host of environmental, socioeconomic, and political factors that promote obesity (39).

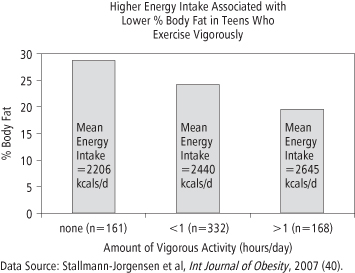

The complexity of the relationships among food intake, physical activity, and body fat content is illustrated in children by workers who examined energy intake, vigorous physical activity, and body fat percentage in three groups of teens: those who exercised vigorously an hour or more a day; those who exercised vigorously less than one hour a day; and those who did not exercise vigorously (see Figure 27-3) (40).

Figure 27-3 Data illustrating that higher levels of daily vigorous physical activity are associated with higher mean energy intake but lower percentage body fat

As might be expected, vigorously active children have the lowest percent body fat compared to either their less active or sedentary counterparts. Note in Figure 27-3 that the most active children consume the most calories and yet they are the leanest group. The fact that the vigorously active children eat the most calories and have the lowest percentage body fat, whereas the fattest children are eating the fewest calories, illustrates that assessments of either food intake or physical activity alone can be seriously misleading. In studies of children, food intake, physical activity, and percentage body fat (or a body fat surrogate such as sex- and age-specific BMI percentile) should be taken into account in the design and evaluation of a childhood obesity prevention strategy. Because obesity prevention interventions in children are necessarily of long duration, the expense of measuring all of the relevant variables is considerable. This is one of the factors hampering prevention research.

Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Prevention

The IOM (39) has offered a conceptual framework for childhood obesity prevention based on the segment of the population targeted and the purpose of the intervention:

- Primary prevention: Universal or population-based efforts directed at a target population seeking to prevent obesity from occurring in the first place.

- Secondary prevention: Selective or high-risk prevention focused on individuals (e.g., those who are overweight or those with a normal weight but exhibiting an escalating weight trajectory) identified to be at high risk for obesity.

- Tertiary prevention: Targeted or indicated prevention focused on those already afflicted with obesity; seeks to stem negative consequences (such as type 2 diabetes or other illness).

A primary prevention strategy for childhood obesity would target all children in a population and might include monitoring or screening children in order to assess them and identify nascent problems before any of the children become obese. A secondary prevention strategy recognizes that at least some children may already be categorized as overweight or even obese, but seeks to prevent further weight gain and sometimes weight loss. A tertiary prevention strategy is one in which the children are categorized as obese, and the goal is to remediate or reverse the comorbidities of obesity such as type 2 diabetes. The primary prevention of obesity in a school-based setting is discussed in Chapter 26 and secondary prevention, or treatment, of childhood obesity is discussed in Chapter 25. Tertiary prevention would include surgery (Chapter 19), but is controversial for children.

The Ecological Model

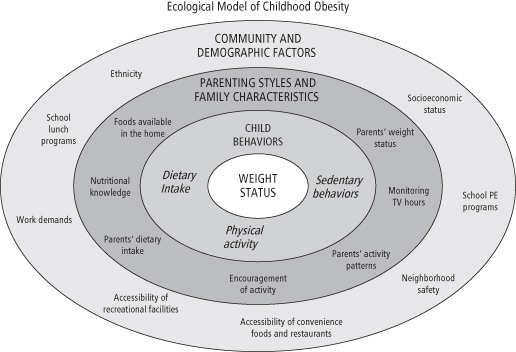

The IOM has called for a multilevel approach to childhood obesity prevention (39). This approach is informed by the ecological model developed by Davison and Birch (41) depicted in Figure 27-4.

Figure 27-4 A model illustrating the context and many factors that affect the weight status of a child

The ecological model represents the entire social, biological, and political context in which a child’s weight status is shaped. The model helps identify the roles and responsibilities of individuals or groups for obesity prevention. For the sake of prevention strategy development, it permits the identification of roles for federal, state, and local government leaders and agency directors, for industry (food, beverage, restaurant, media, entertainment), for marketers and advertisers, for community leaders, schools, and preschools, as well as families, including parents, siblings, and all other primary caregivers. The framers of several IOM reports relevant to childhood obesity have taken the position that childhood obesity prevention should be a national priority requiring visionary and aggressive leadership on all levels, and that an effective prevention campaign must address all of the factors on multiple levels simultaneously. In the remainder of this chapter, a small subset of recommendations will be discussed, but the serious student of childhood obesity prevention is encouraged to read these reports in their entirety (14, 39, 42–45).

The prevention strategies addressed in this chapter focus primarily on settings in which specific changes in behavior thought to prevent childhood obesity might be supported. The behavioral changes include decreasing sedentary behavior, increasing physical activity, increasing exclusive breastfeeding, decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption, and increasing the availability and consumption of foods that are high in nutrient density but low in energy density (e.g., fruits and vegetables). These strategies have been selected based on the best available evidence of effectiveness, although it is acknowledged that this is not always the best possible evidence (14, 39, 45). In view of the growing number of obese women of childbearing age, we discuss the relationship between maternal obesity and obesity in offspring and the need to reduce the prevalence of obesity among women of childbearing age as a prevention strategy. The science supporting each strategy is described in detail and research needs are identified throughout.

Settings for Prevention: It Takes a Nation

Having reviewed the rationale for supporting childhood obesity prevention as a national health priority, we now explore what could be done in various settings if obesity prevention were accorded this status. We also examine what is (and is not) being done, and identify actions that we believe would be beneficial in addressing obesity prevention with the commitment it deserves in the following settings:

- Media and the marketplace

- Home/families

- Healthcare/clinical

- Schools

- Community settings

- Worksites

Media and the Marketplace

Children spend a significant amount of money on food, either directly or by persuading their parents to make certain purchasing decisions through “pester power.” Marketers know the commercial importance of placing their products at the eye level of children and they are willing to pay grocers to ensure that their products are optimally placed. The placement of gum and candy at the checkout is just one example of strategic product placement. In the typical supermarket, we are literally surrounded by foods and beverages that have been formulated and packaged to appeal to children. Total marketing expenditures of the food, beverage, and restaurant industries collectively could not be ascertained, but advertising alone accounted for more than $11 billion in 2004 (43). It is also estimated that food and beverage companies spend $1.6 billion on advertising to children directly (46). There is a shift in the food, beverage, restaurant, and entertainment industries toward spending marketing dollars on “unmeasured sales promotion” such as character licensing, product placement, special events, in-school activities, and advergames (see www.digitalads.org). The point of industry spending on marketing to children is to influence the more than $200 billion that children spend directly, and an equal amount that they influence through pester power (43).

The IOM published a landmark report, Food Marketing to Children and Youth: Threat or Opportunity (43), which concluded that TV advertising influences children, especially 2–11-year-olds, to prefer and request high-calorie/low-nutrient foods and beverages. What are children spending their money on? The leading categories are candy, carbonated soft drinks, and salty snacks, according to the IOM, and there is little debate that such purchases lead to increased consumption of heavily advertised foods and beverages (43).

A fundamental issue underlying the debate about marketing to children is the “stages of discernment” of children. This refers to the perceptual and cognitive development of children (43, 47). Before a certain age, children lack the ability to discriminate commercial from noncommercial content. Children who have not developed this level of discernment are unable to distinguish the difference between program content and advertising. They accept advertising at face value and do not understand that advertisements are designed to urge them to make certain purchasing or other behavioral decisions about the products being advertised. Children generally develop powers of discernment at about age of 8 years, but children as old as 11 years may not do so without prompting (47). Kunkel and colleagues (47) describe three important trends that sharpen this debate. First, unlike 30 years ago, current children’s programming spans the entire day and exposes them to many more commercial messages embedded in their programs (>40,000 per year). Second, characters from children’s TV programs and movies are now embedded in the advertisements, thus intentionally blurring the distinction between programs and advertisements. Third, the Internet and cell phones represent new conduits for commercial messages directed to children throughout the day. Through Channel One and other forms of advertising in schools, children are literally surrounded by commercial messages all day, every day. Because of children’s undeveloped critical and discriminatory powers, the American Psychological Association has argued that advertisements targeting children below the age of 8 are unethical and manipulative (47). Their report argues that children deserve special protections from all commercial messages until they are mature enough to clearly discern and critically interpret their commercial persuasive intent (47).

This is not new information or new thinking about protections needed for children. Based in part on a research review conducted by the National Science Foundation in 1977 (48), the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) issued its own 300-page report (49) and initiated a rulemaking process about this issue in 1978. They raised the question of whether advertising to young children should be restricted or banned as a protective measure. This effort by the FTC ended only because industry pressure (by lobbying) mounted, and Congress intervened and cut off funds to the FTC. The FTC capitulated and terminated the ruling in 1981. Since then, the marketing strategies employed by industry are considerably more pervasive, targeting all media, including cell phones, the Internet and the web, school gyms and playing fields, sports arenas, billboards, and buses, in order to reach children with their commercial messages.

The Congressional response to the FTC ruling was considered at the time to be reflective of the public’s perception that the FTC was overreaching itself—i.e., going beyond its proper role. In “Advertising to Kids and the FTC: A Regulatory Retrospective that Advises the Present” (50), Beales and colleagues warn that a similar attempt to ban advertising today would be even more inappropriate because parents have so many ways to prevent children from viewing advertising (e.g., by restricting them to commercial-free programs) and there are so many technologies available (such as TiVo) that permit parents to strip out advertisements from commercial programming. In short, these authors argued that the FTC action was not a proper role of government and that the FTC was, in effect, usurping the proper role of parents. Not everyone agrees and certainly one wonders if the parents today would agree.

The Beales’ analysis asserts that FTC staff concluded that the proposed ban would be impractical because it would have been nearly impossible to implement (50). This conclusion was based on the viewing behavior of audiences and programming available in the 1970s and on the fact that the FTC framed its argument on scientifically muddled claims about the cariogenicity of sugary foods marketed to children. It is noteworthy that the analysis states that there was little evidence at the time that TV advertising of sugary foods led to increased consumption of the foods (50). It seems unlikely that advertisers would spend billions of dollars on advertising if consumption patterns were unaffected; however this has not been directly studied. Thus, independent documentation of the connection between advertising to children and the purchasing and consumption patterns of children as well as their body weight status is an important research need.

Though the FTC was unsuccessful in 1978, the ubiquitous commercial environment in which children now live, combined with the rapidly growing epidemic of childhood obesity and growing prevalence of obesity-related illnesses, may finally provide the basis that the FTC would require to ban advertising of foods to children. Another retrospective review of the unsuccessful attempt by the FTC to ban advertising to children (51) concludes that the ban now would be more likely to rely on an “unfairness” argument that rests on the existence of “consumer injury” which would have to meet at least three criteria: 1) the injury would have to be substantial; 2) the injury must not be outweighed by countervailing benefits to consumers or competition; and 3) the injury must not be reasonably avoidable by the consumers themselves (51). The very fact that our children are increasingly obese and falling ill and even dying from obesity-related illness may finally persuade Congress that their intervention with the FTC in 1978 has had catastrophic consequences. Today they may finally conclude that the ban on commercial advertising directed to young children, considered by the FTC nearly 30 years ago, should have gone forward.

This does not seem to be the case, however. In July 2008, the FTC released a report to Congress, “Marketing Food to Children and Adolescents: A Review of Industry Expenditures, Activities, and Self-Regulation” (46). Rather than suggesting a ban on advertising to children, the FTC encourages companies to self-regulate their advertising of food, especially to children under the age of 12. They note, for example, that 13 companies either abolished their advertising to this age group or they only market nutritious foods to this age group (46).

The IOM marketing report cited above (43) does not call for a cessation of commercial advertising directed at children under 12. For this reason, some would argue that the report falls short of what is needed to prevent childhood obesity. Nonetheless, the IOM’s recommendations are a good starting point for the development of a national initiative to prevent childhood obesity (see Box 27-1).

Box 27-1 Selected Recommendations from the IOM Marketing Report

1. Calls on industry to formulate foods and beverages that are “substantially lower in total calories, lower in fats, salt, and added sugars, and higher in nutrient content”

2. Calls on industry, government, scientific, public health and consumer groups to develop an industry-wide, graphic rating system (appealing to children and youth) for use on product labels to convey the nutritional quality of foods and beverages

3. Calls on restaurants to offer healthier food, beverage, and meal options for children and youth

4. Calls on restaurants to provide prominently visible calorie content on menus and/or at the “point of choice” (e.g., a menu board on the wall)

5. Calls on trade associations to develop industry-wide food and beverage marketing standards, including in venues where parents and children shop, and assure compliance

6. Calls on trade associations to share technical know-how for healthier product formulation

7. Calls on trade associations to foster collaboration and support for public sector initiatives promoting healthful diets for children and youth

Note that the second recommendation calls on industry to develop an industry-wide graphic based on a rating system of the nutritional quality of foods and beverages. Although some companies attempted to collaborate in the development of a program that would rank foods using a front-of-package label to guide consumer choices (e.g., the International Food and Beverage Alliance, www.ifballiance.org), for the most part, each company developed its own system and graphic. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) wrote to the administrator of one such program—the Smart Choices® program—and this led to a halt in the implementation of that program (52). The fourth recommendation on calorie labeling of menus will be implemented in chain restaurants with 20 or more outlets nationally as a part of the recently passed healthcare reform legislation (53). In the view of many concerned individuals and organizations, marketing to children remains largely unaddressed. An Interagency Working Group, with representatives from the FTC, the CDC, the FDA, and the US Department of Agriculture, was tasked to develop model nutrition standards for food marketing to children. As of November 2011 draft voluntary standards are still being hotly debated.

Regulatory Strategies

In the interest of public health, the sale of products associated with negative health outcomes, such as cigarettes and alcohol, is regulated through several mechanisms. In addition to regulating the marketing and sale of potentially dangerous products, the government sometimes imposes a tax on these items as a way of discouraging consumption and funding prevention and treatment programs and other measures. Similarly, local, state, and federal policies often prohibit the use of certain products in specified areas; for example, in most states, alcohol cannot be consumed in a moving vehicle, and cigarettes may not be smoked in most schools, restaurants, and worksites. Furthermore, the government sometimes imposes fines or other sanctions when individuals engage in dangerous activities such as driving a car without using a seatbelt or riding a motorcycle without wearing a helmet. These types of regulations have proven to be extremely effective in changing dangerous behaviors. In general, however, attempts to translate regulatory strategies directly to obesity prevention have been controversial and have not been adopted on a wide scale, partly because of the absence of data demonstrating that they are effective in preventing childhood obesity.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC), the agency that is the “trustee for the public airwaves,” has established a task force (see www.fcc.gov/obesity) to examine the issue of marketing to children. Both Senators Brownback (Republican, Texas) and Harkin (Democrat, Iowa) have participated in the FCC task force, although this body has no regulatory power, nor has its effectiveness been assessed. The Obama administration assembled its own Childhood Obesity Task Force (54), which included members of many federal agencies. In early 2010, the Task Force unveiled its action plan to eradicate childhood obesity within a generation (54). The effectiveness of the plan of action set forth by the Task Force, which included some proposals to limit advertising to children, has not yet been determined, and the ability of the Task Force to establish regulations to combat childhood obesity remain to be seen.

Not only policy-setting bodies but also the public at large—through public pressure generated by researchers, the media, advocacy groups, and others—can encourage key players to improve their sales and marketing techniques, even in the absence of legal regulations. In response to such pressure, the American Beverage Association (www.ameribev.org) has established guidelines for providing sodas in school vending machines, although some have criticized the ABA guidelines as too lenient (see www.cspi.org). Many countries have stricter regulations than the US on marketing to children (see Box 27-2), but the World Health Organization (WHO) has issued a report that says that from 2004 to 2006, from a global perspective, there has been more talk about regulation than action (55).

Box 27-2 Some Regulatory Activities of European Countries

1. Sweden and Norway do not allow advertising to children under 12. This ban was accomplished by legislation. (Note: Because of their small size, many countries in Europe receive programming and advertising from neighboring countries over which they have no control, potentially eroding the effectiveness of a ban.)

2. France is preparing mandatory health messaging for radio and television that will stream on all ads for anything considered a processed food. More legislation and regulation is expected.

3. The Dutch code includes a ban on celebrity and character endorsements in advertising aimed at children.

4. Spain’s Minister of Health has called for a ban on advertising to children.

5. Canada’s rules protect all children under 12 years of age. Puppets, persons, and characters (including cartoon characters) well known to children and/or featured on children’s programs must not be used to endorse or promote products, premiums, or services. All children’s advertising must receive authorization from the Children’s Clearance Committee prior to broadcast.

6. In the UK, legislation, which has not yet fully taken effect, will protect children under 16 years old. The rule states, “food and drink products may not be advertised in any programme that is made for children (including pre-school children) broadcast on any channel or in any programme that is of particular appeal to the under 16s … In addition, there are new rules on the content of advertisements which apply to all advertising of food and drink products to all children at all times.” The rules provide an additional level of protection for pre-school and primary school children.

Source: Robert Kesten of the Center for SCREEN-TIME Awareness (www.screentimeinstitute.org)

The food company Mars, Inc. announced that it would cease the marketing of candy and other confectionery products to children under the age of 12 as of January 2008. Since many confectionery products are sold through vending machines, it should be noted that the decision regarding which products are placed in vending machines in schools, parks, zoos, or other venues in a community is made at the local level, often by school administrators who are worried about budgetary issues and desire the sales revenues generated through vending machines for candy and “pouring contracts” for soda machines. Since it may not be widely known that such decisions are under local control, parents, caregivers, educators, and policy-makers need to know they can profoundly influence marketing to children in schools and elsewhere in the community. Regardless of the FCC deliberations, the message that such decisions are under local control needs to be communicated to the general public so that parents understand that they can get involved in the establishment and implementation of wellness policies. These policies can set nutrition standards for foods sold and served in their local schools.

The Food and Beverage Industry

As mentioned earlier, the IOM has called on the food and beverage industry to formulate products that are substantially lower in calories and higher in nutrient density and to refrain from marketing products that do not meet these higher standards to children. This raises the question of what those standards should be. Among members of the FCC task force, this debate often devolves into which foods or beverages meet the standards for “healthy” and which do not. In 2007, the IOM compiled a set of standards for foods served or sold in schools (44). The standards set the following limits:

- Fat—No more than 35% of calories from fat per portion.

- Sugar—No more than 35% of calories from sugar, with certain exceptions that would permit fruits, 100% juice, and certain dairy products to be sold or served in schools.

- Calories—No more than 200 kcal per portion for snacks; calorie limits for entrées would be guided by calorie limits for foods offered through the National School Lunch Program run by the US Department of Agriculture.

- Sodium—200 mg or less per portion.

The beverages recommended by the IOM as permissible during the school day are noncarbonated, non-flavored, and caffeine-free and include plain water, 1% and nonfat milk (or the equivalent in soy milk, lactose-free milk, or flavored milk with no more than 22 g of total sugars per 8 oz portion), and 100% juice in limited portions (8 oz for high school students, 4 oz for younger students). Some have argued that such standards are arbitrary and inappropriate and that banning or limiting advertising to children is logistically difficult, if not impossible, and may infringe on the First Amendment (free speech) rights of older viewers.

The Restaurant Industry

A development with national repercussions for the restaurant industry took place in New York City in the fall of 2006 when the city’s Department of Health (56) proposed that the posting of calories on menus and menu boards be required in certain restaurants. After two years of legal battles with the New York State Restaurant Association, restaurant chains with 15 or more stores were required to post calorie information on menus and menu boards (57). Since most Americans consume a substantial number of calories outside the home each day, the goal is to arm consumers with more information at the point of decision-making. The National Restaurant Association says that their research shows that “95% of survey respondents feel they are qualified to make their own dietary choices, and more than two out of three (68%) say they are tired of the ‘food police’ telling them what to eat” (58). With the advent of healthcare reform, and nationwide nutrition labeling in restaurant chains of 20 or more outlets (53), researchers are presented with an opportunity to evaluate the long-term effectiveness of posting calorie information for obesity prevention.

Many of the larger food chains already offer calorie information, either on their websites or in publications and handouts available in retail outlets. It appears that public pressure was sufficient to include provisions to require the posting of such calorie information at the point of decision-making in America’s 935,000 restaurants and food service outlets (59) as a part of healthcare reform. In areas implementing such policies, an important research need is to document how these policy changes influence the behavior of children and their parents, taste preferences, food and beverage selection and consumption, and BMI.

The Entertainment Industry

Characters, cartoon figures, and celebrities from children’s movies and TV programs are frequently used in product advertising. It is argued that the strong appeal of such characters to children represents unfair manipulation and may be harmful to children when used to endorse or promote foods of high calorie content and low nutrient density. In fact, the FTC report discourages their use (46). Others seek to use such characters to promote healthful eating and exercise habits. The Campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood criticized the use of the DreamWorks character Shrek in a public service announcement (PSA) developed by the Ad Council on behalf of DreamWorks and the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) (60). The plan was to use Shrek for healthy messaging to children, urging them to be more physically active. But critics pointed out that producers had signed for promotions tied to the release of the film sequel, Shrek the Third. According to an article in USA Today, the products linked to Shrek ranged from Sour Skittles to McDonald’s Happy Meals to Kellogg’s Shrek the Third cereal to special Cheetos that turn mouths green (61). One marketing expert claims that for children aged 6–11 years, Shrek’s familiarity is 94% (the same as that for Mickey Mouse), and Shrek’s “likability” with kids ranks slightly higher than SpongeBob SquarePants—and just below that of Santa (61). Critics worried that children would be confused by the conflicting messages represented by Shrek and since the DHHS campaign rested on voluntary airing of the PSA, the message to boost physical activity would likely be swamped out by the food messages linked to Shrek supported by millions of dollars of food industry-paid advertising power.

When public health activists began to make efforts to decrease smoking, one of the avenues pursued was banning cigarette advertisements from television. If we were to take the danger of childhood obesity as seriously as we take the danger of smoking initiation, we might ban all commercial advertising and marketing to children, especially TV ads for high-calorie, low-nutrient foods. Potentially harmful substances such as alcohol and tobacco cannot be sold to minors, and even when sold to adults they must carry warning labels. No such restrictions apply to the marketing of high-calorie, low-nutrient foods, nor have they been proposed. Thus, attitudes appear to differ greatly when comparing the public health response to the threat of smoking to the response to the equally serious threat of childhood obesity.

Home/Families

While the government is able to pass laws prohibiting the sale of alcohol or tobacco to minors or require that food labels carry certain calorie or portion size information or even health warnings, laws regulating the home environment are more controversial. Laws do regulate some parenting behaviors; for example, young children below a certain weight must be placed in car seats if they are to ride in cars, use of seat belts is required by law, and children must be sent to school (or otherwise educated to a minimum standard). Severe obesity in childhood in some instances is considered to be a form of child neglect (62). Case studies from California, Iowa, Indiana, New Mexico, and Texas describe instances where children have either died or were removed from their families because of severe obesity (62). A major challenge is how to assist parents seeking to prevent childhood obesity, especially single parents or parents who need to hold more than one job and who must work long hours in order to pay for housing and other basic necessities. Other challenges include helping parents to assess childhood obesity and to identify it as a genuine health threat, and motivating them to take constructive action. Perhaps most challenging of all is how to help parents offset the billions of dollars spent on marketing unhealthful foods and a sedentary lifestyle to children. It has been suggested that parents can do this by serving as positive role models and by using messages and home policies that reinforce healthy eating and physical activity (39, 43).

Public health media campaigns can shift social norms and address parental behavior. An example is the TV ads, radio spots, and billboards dedicated to the “Parents: The Anti-Drug” Campaign (www.theantidrug.com) intended to discourage teen drug use. Churches, PTAs and PTOs, Kiwanis Clubs, Rotary Clubs, and a wide variety of other organizations might be mobilized to reach out to parents to help them prevent obesity among their children. But evidence is lacking on how to design and implement such campaigns, how to craft the messages to motivate positive changes and how those messages should be effectively delivered to busy, overworked parents at all socioeconomic levels. A national initiative to address childhood obesity, such as the Childhood Obesity Task Force of the Obama administration, may or may not have the political support to mount such a prevention campaign, but could surely stimulate and facilitate the necessary research, development, and evaluation.

The Role of Parenting

A national opinion poll of more than 1,000 adults, conducted in the spring of 2004 by RTI International, found that the vast majority (91%) of respondents view parents as playing a major role in stemming the childhood obesity epidemic (63). Another poll (64) reached a similar conclusion. In other words, the American public believes that parents are central to this issue. Yet very few interventions incorporate parents and parenting as the central feature (65–67). The IOM report on childhood obesity prevention (39) and a review by Golan and Crow (68) suggest that parents have a role to play in the prevention of childhood obesity by shaping their children’s eating and activity habits, building a positive body image and self-esteem, and making policies that can help mitigate environmental factors that promote obesity. But it concludes that the evidence is scanty and more research is needed.

Parents play three key roles in the home that can influence the development of childhood obesity. In addition to their genetic contribution to their offspring, over which they have no effective control, parents serve as role models, policy-makers, and environmental change agents. The IOM’s overall recommendation to parents is to “promote healthful eating behaviors and regular physical activity for their children” (39). Specific ways in which to implement this recommendation are summarized in Box 27-3 and each will be discussed further below.

Box 27-3 Recommendations for the Home

Parents Should Promote Healthful Eating Behaviors and Regular Physical Activity for Their Children

To implement this recommendation parents can:

- Choose exclusive breastfeeding for feeding infants for the first 4–6 months of life.

- Provide healthful food and beverage choices for children by carefully considering nutrient quality and energy density.

- Assist and educate children in making healthful decisions regarding types of foods and beverages to consume, how often, and in what portion size.

- Encourage and support physical activity.

- Limit children’s TV viewing and other recreational screen-time to less than two hours a day.

- Discuss weight status with their child’s healthcare provider and monitor age- and sex-specific BMI percentile.

- Serve as positive role models for their children regarding eating and physical activity behaviors.

Adapted from IOM. Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2005 (39).

Parents As Policy-Makers

The importance of establishing and maintaining household routines for very young children was illustrated by a cross-sectional analysis of national data on 4-year olds assessed in 2005 in the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study. These workers found that three household routines were particularly important: regularly eating the evening meal as a family, obtaining adequate (>10.5 hours) nighttime sleep and limiting TV and other screen-time viewing to less than two hours a day (69). Factors such as improving the nutritional quality of foods offered in the home, increasing physical activity, and decreasing time spent watching TV and other recreational screens are discussed elsewhere in this chapter, but a few studies of sleep are discussed below.

Chaput and colleagues (70) found a strong inverse relationship between sleep duration and the risk of developing obesity. In 422 children (50% boys) between the ages of 5 and 10 years, the odds of obesity were lowest in children who reported sleeping 12–13 hours a day. By comparison, children who slept 10.5–11.5 hours a day had a significantly increased likelihood of obesity. The risk of obesity more than triples among children sleeping only 8–10 hours a day. One research question that this cross-sectional study cannot answer and that needs to be addressed is whether obesity is interfering with sleep or whether disordered or inadequate sleep is causing or contributing to the development of obesity.

It is well known that obesity in children is associated with sleep apnea or a temporary cessation of breathing during sleep (71). Apneic episodes increase with severity of obesity and can cause a number of deleterious physiological and metabolic effects. In one study (72), sleep-disordered breathing was significantly more prevalent among 132 obese children and adolescents than in 453 normal-weight school children who served as controls. Tzischinsky and Latzer (73) conducted a study of sleep–wake cycles in obese children (n = 36) by means of mini-actigraph monitors (which measure motor activity), which the children wore for one week. Among obese children, 37% reported uncontrolled binge-eating episodes. These workers found that sleep disruption in obese children suffering from binge-eating was significantly more severe than in obese children who were not troubled by binge-eating or among normal-weight (n = 25) controls. The role of sleep in the development and prevention of obesity is an area in which considerably more research is needed.

Self-Regulation and Parents As Role Models and Facilitators of Healthy Eating

Researchers who study the feeding behavior of children invoke the concept of “self-regulation,” which is the notion that healthy children have functional internal physiological cues signaling hunger and satiety, and that if they learn to “listen” to these signals they will avoid overeating and obesity. To support this concept, people cite the classic feeding study of Clara Davis conducted in the 1920s (74). This study led to a notion that there is an innate “wisdom of the body,” because young, newly weaned children maintained energy balance when given ad libitum access to a variety of foods over extended periods of time with no parental attention to the amount of food the child consumed. It is not widely appreciated, however, that all of the foods offered in this widely cited study were wholesome (75). In other words, the design of this study did not challenge these children to choose between healthful and less healthful food choices in an environment saturated with media messages to eat a variety of high-calorie foods and drink soda and other sugar-sweetened beverages.

Today, significant numbers of children are weaned on chips, French fries and sugar-sweetened beverages (76) that are carefully formulated and tested to be especially appealing to children. These products cater to children’s preferences for sweet taste, which is thought to be innate, and for salty flavor, which develops early in infancy (77, 78). Food preferences strongly influence food intake and shape the foundation of one’s customary diet (79); thus, wholesome foods and beverages should be particularly emphasized during infancy and childhood.

Parents are responsible for the foods and beverages that are brought into the home and routinely made available to infants and children. This is a challenge, as parents’ and children’s food choices are influenced by the marketing efforts of the food industry, as we have discussed previously. A national childhood obesity prevention strategy would not only protect children from commercially driven persuasion, but would harness marketing savvy to shape healthier eating and lifestyle habits for children and the entire family. In the meantime, parents are in a quandary. Do they restrict foods they know are not good for their children but are heavily advertised and are designed to be preferred, or do they include such foods among those made available in the home? Studies in laboratory settings suggest that restriction is ill-advised because it leads to stronger preferences for forbidden foods (80–82). The recommended course of action is for parents to offer predominantly nutritious foods to their children and as soon as they are able, to allow children to serve themselves without parental comment or coercion (83). Foods and beverages of minimal nutritional value can be available for occasional use rather than banned altogether.

It is not unusual for parents to lament that fruits and especially vegetables are unappealing to their child. There are studies demonstrating that parental modeling by consuming a particular disliked food (or beverage, such as milk) will enhance the likelihood of acceptance (84). Furthermore, it has been shown that repeated offerings of a food (as many as 10 times might be necessary) leads to eventual liking and acceptance of that food by the child (85–88).

Coaxing a young child to eat new foods is a familiar action in most families with young children. One study (89) demonstrated that young children are more willing to taste novel foods if the mother samples the new food first. A similar study showed the importance of parental modeling of fruit, juice, and vegetable consumption (90). Qualitative research shows that children are aware of what their parents do and do not eat, and further that children of various ethnicities report lack of parental modeling as the key reason they refused to eat certain foods (91). Birch and coworkers have played a leading role in demonstrating that parental consumption patterns and food preferences have a significant influence on the same behaviors in children (84, 92). On balance, this extensive body of research demonstrates that parental modeling of healthful food choices, repeated offerings of novel foods, and non-coercive encouragement of specific healthful foods have a beneficial effect on the eating behavior of offspring.

In older children, a study of factors favoring healthy eating among 11–16 year olds (93) identified several important facilitators:

- Family support for healthy eating.

- Availability of wholesome foods and beverages in the home.

- Desire to take care of one’s appearance.

Of equal importance to the quality of the diet is the quantity of food offered to children. The portions offered to children are often inappropriately large for their age—a factor that has been shown to lead to overeating and eating in the absence of hunger in children as young as 5 years old (94). This is yet another reason that parents are encouraged to allow a toddler to self-regulate food intake by serving him- or herself as soon as the child is old enough to do so.

There is evidence that using food as a reward for good behavior or for manipulating the mood of children is ill-advised (85). One retrospective study found an association between using food rewards in childhood and subsequent chronic struggles with dieting and binge-eating in adulthood (86). Using food as a reward should be discouraged.

Obesity prevention studies seeking to leverage parental influence on adolescents have sometimes led to inconsistent results, possibly because the teenage years are often marked by adolescent rebellion and rejection of parental influences, difficult social and emotional adjustments, and the emergence of peer influence on teens. Research is needed to evaluate whether positive parental influences on feeding behavior re-emerge after the rebellious adolescent years end. Most authoritative sources on childhood obesity prevention, such as the IOM, urge parents to take control of the home environment, including food and beverages offered in the home, actively monitor their children’s behaviors, and offer non-food rewards for physical activity and other positive behaviors that favor energy balance and healthy weight maintenance (39, 95).

Parental Eating Behavior and Exercise of Control

“Feeding is the area of a child’s life where nutrition, parenting, and human development meet.”

C. W. Slaughter and A. H. Bryant, Hungry for love: The feeding relationship in the psychological development of young children. The Permanente Journal 2004; 8: 23–9

The question of how parental control over their own and their children’s eating behaviors affect their children’s weight trajectory is of considerable interest. Not only is this a delicate topic because of family privacy issues, but there is a body of evidence suggesting that parental attempts to restrict and control children’s eating and weight may backfire—producing the very problem that parents are seeking to avoid (79–81). Validated instruments have been developed as research tools to evaluate the effect of parental control on children’s eating behaviors and weight (96–99). Two important parental eating behaviors—dietary restraint and disinhibition—appear to be important. Dietary restraint refers to the conscious restriction of food intake to control weight (100). Disinhibition refers to the abandonment of control of food intake triggered by external food cues or circumstances (101). Thus, a parent who frequently diets to control weight, but frequently gives up and goes on eating binges, would be an example of a dietary restraint behavior coupled with disinhibition. The Framingham Children’s Study offers data demonstrating that parental eating behaviors can influence the eating behavior of their offspring. Hood and colleagues (102) found deleterious effects of parental disinhibited eating coupled with dietary restraint, namely, increased skinfold thickness and BMI of their offspring. Their analysis suggested these negative effects were most pronounced when both parents exhibited the combination of dietary restraint and disinhibition.

What is unclear is how, or through what mechanism, these parental behaviors influence the child. Does the child lose the ability to detect or respond to his internal cues of hunger and satiety because of imposed parental food restriction and disinhibition? Or does the child simply imitate the parent’s behavior?

The combination of disinhibition and restriction is associated with adult obesity and the onset of obesity may have a genetic underpinning. Thus, the obesity of the child born to parents exhibiting such behaviors may reflect genetic endowment or may reflect a learned response. An important research question is whether these parental behaviors can be managed or modified for the sake of preventing childhood obesity in their offspring. As mentioned previously, direct marketing of foods to children has a strong effect on food choices, and it may be possible that any parental control or internal physiological cue in the child may be overridden by this marketing, making research in this arena especially difficult.

Epstein and colleagues (103) evaluated a parent-focused targeted behavioral prevention intervention in families with at least one obese parent in which the children were of healthy weight (BMI < 85th percentile) and between 6 and 11 years of age. The families were randomized to two groups and both groups were given a comprehensive behavioral weight-control program. One group was encouraged to increase fruit and vegetable intake and the other was encouraged to decrease intake of high-fat/high-sugar foods. The children were given materials that matched those of their parents but child materials did not restrict calories, whereas parent materials did. A total of 15 families began in each group and, at the end of one year, 27 families (90%) completed the protocol. The weight-control program for parents was based on the “Traffic Light Diet,” which groups foods into three categories—red, yellow, and green—based on calories and nutrient content. Green light foods are lowest in calories and highest in nutrient content. They include most vegetables and are not restricted. Yellow foods are caution foods: higher in calories, but they deliver important nutrients needed for a balanced diet. Red light foods are highest in calories and lowest in nutrient delivery. Red light foods such as cakes and cookies should be eaten sparingly. In this study, the Traffic Light Diet was taught to parents in eight weekly meetings, followed by four biweekly meetings and two monthly meetings. The children came only to the first meeting in which the parents and children were given the first modules in their workbooks. The diet was used to promote healthful eating and a balanced diet in all parents, and weight loss in the overweight parents. Parents were also taught behavior change techniques and how to foster and reinforce targeted behaviors in their children using non-food rewards. In the “Increase Fruit and Vegetable” group, the goal was to teach parents to reinforce behaviors that incrementally moved toward the goal of eating two servings of fruits and three servings of vegetables per day. Parents in the “Decrease Fat and Sugar” group reinforced behavior that moved toward the goal of “no more than 10 servings” of high-fat/high-sugar foods per week. Child materials were sent home with parents each week and included assignments that the parent and child should do together. Both groups of parents worked with a therapist and were given a physical activity goal of performing at least 30 minutes of moderately intense physical activity on six or more days per week.

A key finding was that parents who targeted and reinforced increased fruit and vegetable intake successfully increased intake of fruits and vegetables. The unexpected dividend in this group is that the intake of high-fat/high-sugar foods spontaneously decreased and the decrease was significant in the parents and in their children. In the group that targeted and reinforced decreased high-fat/high-sugar foods, parents achieved reductions in the intake of those foods in themselves and in their children, but they achieved no beneficial change in fruit and vegetable consumption. Weight loss was achieved in both groups, but the fruit and vegetable group lost significantly more weight.

These workers concluded that the greater success of the fruit and vegetable group, emphasizing what can be eaten rather than what cannot, may be a more effective strategy in reducing overall calorie intake. The study demonstrates that focusing on parental change and providing materials for parents and children to use at home may be useful as a prevention strategy—a finding consistent with studies targeting only parents in the treatment of childhood obesity (104, 105). A major limitation is that this study involved very few families because it was difficult to recruit overweight parents with normal-weight children who were interested in childhood obesity prevention (103). In other words, prevention of childhood obesity is not widely valued or considered a priority at this time. Given the widespread prevalence of overweight and obesity among parents, this study suggests that an intervention that targets the overweight parent of a normal-weight child can yield beneficial results in both the parent and child and may thus offer a cost-benefit advantage. The question of how the cost of such an intervention would be covered in a real-world setting would have to be addressed as an important component of a national initiative to address childhood obesity.

Prevention and Treatment of Obesity in Parents and Parents-To-Be

One way to prevent obesity in early childhood is to treat obesity in parents or parents-to-be (see also Chapter 10). Obesity in parents, especially mothers, predisposes their offspring to childhood obesity (106–109). One study of nearly 8,500 low-income children born in the 1990s (107) found that children born to obese mothers were more likely to become obese preschoolers. By 4 years of age, obesity was present in almost 25% of children who were born to obese mothers. This compares to fewer than 10% of children who were born to normal-weight mothers.

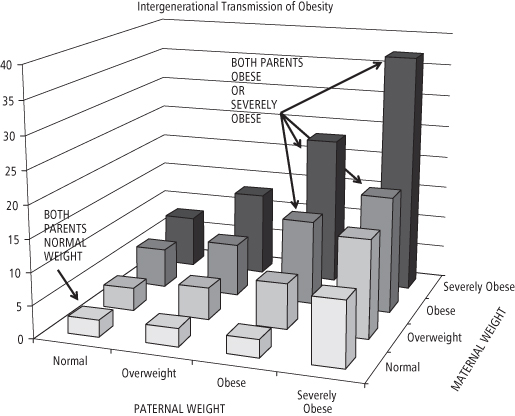

The presence of obesity in fathers also raises the risk of obesity in the child (9, 107, 109). The interaction between the severity of maternal and paternal obesity on the transmission of obesity to their offspring is graded (see Figure 27-5) that is, the more severe the parental obesity, the greater the risk to their children (109).

Figure 27-5 Data showing the effect (and interaction) of parental weight status on the risk of childhood obesity (109)

If both parents are severely obese (defined as a BMI of 40 or higher) the risk of childhood obesity increases 10-fold over that seen in the offspring of normal-weight parents (107, 109). Thus, public health efforts to prevent childhood obesity should reduce the growing prevalence of severe obesity, which is the fastest growing segment of the obese population, and reduce obesity in children and adults of reproductive potential in order to stem intergenerational transmission of childhood obesity.

High maternal pre-pregnancy BMI is the most important factor contributing to childhood obesity in the offspring, but the prevalence of obesity in pregnancy is increasing with time. One regional study in the southern US found a prevalence of 16% in 1980 but higher than 37% in 1999 (110). Data collected in nine of the 50 states show that 13% of pregnant women were obese in 1994, but 22% were obese by 2003 (111). This ominous trend of increasing obesity among pregnant women is due in part to the fact that the number of obese women of childbearing age (20–39 years old) is steadily increasing and is now 34% nationwide (112). There are ethnic differences in obesity prevalence in women of this age group: White (31%), Mexican American (40%), all Hispanic (38%), and Black (47%) (112).

The rates of severe pre-pregnancy obesity are increasing (113). More and more women are entering pregnancy weighing more than 90, 113, or even 136 kg (110). Severe obesity has now reached 8% in US women of reproductive age (112). This jeopardizes their pregnancies and increases the rates of early miscarriage and congenital anomalies (114); it also raises the risk of gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes, caesarean delivery, infant injury and mortality, and maternal mortality (114)—all of this is in addition to jeopardizing the long-term health and well-being of their offspring by raising the risk of childhood obesity.

There are several factors contributing to increasing rates of obesity and severe obesity in pregnancy. One is the sharp increase in childhood obesity among girls between 6 and 11 years of age (1). Once established at this age, obesity is likely to persist through adolescence and into adulthood (9). Another factor is the increase in obesity among teens. A regional study of more than 700,000 children revealed that 18% of girls ages 12–19 were obese and 7% were extremely obese (5). Nationally, 17% of teens are obese (1) but there are large ethnic differences. Obesity in White teens is slightly lower than the average at 14.5%; in Hispanic teens the prevalence is 17.5%, and in Black teens it is 29% (1).

Another factor is that girls who are obese develop faster and have earlier menarche (115). They are more likely to become sexually active and pregnant while still young and have more children over the long term than those who are not obese (116). These young people are at high risk for unintended pregnancies (116) and their nutritional status is often marginal or poor, both prior to pregnancy (117, 118) and during pregnancy (119). In young girls who are still growing and developing, but whose nutritional status is marginal or suboptimal, an unintended pregnancy represents a severe additional stress and sets up a competition between the mother and the fetus for nutrients. Unintended pregnancies are especially prevalent among economically disadvantaged teens (116).

Excessive weight gain during pregnancy is the second most important factor contributing to the predisposition of the offspring to childhood obesity (120). The mother’s pre-pregnancy BMI category determines the weight gain recommended for an optimal pregnancy outcome (121; and see Chapter 10). The higher a woman’s pre-pregnancy BMI category, the lower is her recommended range of weight gain during pregnancy. For women categorized as obese, the recommended weight gain range is 5–9 kg (121). But gaining within the recommended limits is not typical (120, 122, 123). Only about one third of women gain as recommended; among the two-thirds who gain outside the recommended range, excessive gestational weight gain is nearly four times more common than inadequate gain (113). Obese women are more likely to gain excessively (124), have fatter babies (125), and their children are fatter by the time they reach the age of 4 (107, 124).

Retention of gained weight between pregnancies exacerbates the problems associated with obesity in pregnancy by raising the BMI of the mother for her subsequent pregnancies. Retained weight between pregnancies occurs among women of all racial and ethnic groups, but is most common in Black women. When confronted with obese pregnant women, physicians and other healthcare providers need to be aware that, if they make a specific weight gain recommendation, many women will strive to gain as recommended. Providers should emphasize the critical importance of improving the nutritional quality of the diet rather than recommending that pregnant women simply eat less of their usual diet. It must be emphasized that weight loss during pregnancy is not recommended. Weight loss to achieve a healthy BMI should only be pursued prior to conception or after delivery, but only after lactation is well established (see Chapter 10). Postpartum efforts to minimize retained weight and prevent weight gain are critically important, especially in women who will undergo subsequent pregnancies.

One way to reduce retained weight between pregnancies is through exclusive and long-term (6-month) breastfeeding, which also contributes to protection of the child against the development of childhood obesity (39). But compared to normal-weight women, obese women are less likely to initiate breastfeeding, and they breastfeed for shorter durations if they do initiate (126–129). Data collected on children born in 2005 show that the rates of exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months of age are very low (130). Across all racial and ethnic groups, less than 14% of babies are breastfed exclusively for six months. Among Blacks it is only 6% and in American Indian/Alaska Natives less than 8% (130). It needs to be recognized that breastfeeding—especially exclusive breastfeeding—not only offers optimal nutrition for the child, but also contributes to the goals of reducing body fat in the mother and helping her regain her pre-pregnancy BMI and stem weight gain between pregnancies. Thus, breastfeeding should be recognized as one strategy that operates in multiple ways to prevent childhood obesity.

Studies of the effects of weight-loss surgery in women demonstrate the benefits of achieving a healthy body weight prior to conception. In severely obese women, significant weight loss achieved with bariatric surgery prior to conception is associated with a healthier pregnancy, fewer complications at delivery, and a reduced risk of childhood obesity. These studies of surgical weight loss (35–37) compare babies born to mothers prior to surgery with babies born to the same mothers after surgery. After controlling for the age of the children, the prevalence of childhood obesity was reduced from 35% in children born prior to the mothers’ surgeries to 11% in children born after the surgery (35). It is unclear whether the reduction in childhood obesity is a consequence of changes in the maternal metabolic milieu at the time of conception, in the uterine environment, or improvements in the diet and activity levels of the mother and other caregivers, or some combination of all of the above possibilities. The possible epigenetic effects of maternal obesity on the developing fetal genome is an important research focus. Although these studies are promising, randomized controlled studies of the effects of bariatric surgery on pregnancy outcomes are nonexistent and assessments of long-term consequences are not available at this time. Certainly, treating obesity well before it becomes severe is preferred.

In Canada, some groups are already recommending that gynecological exams should include an assessment of BMI (131). Federal public health officials are organizing to encourage federal and provincial agencies to educate Canadians about the critical importance of entering pregnancy with as healthy a weight as possible (131). Similar efforts in the US at the federal level are urgently needed to break the intergenerational cycle that is propagating obesity and threatening the health of future generations.

Soda and Other Sugar-Sweetened Beverages

The possible role of soda and other sugar-sweetened beverages or soft drinks in the development of childhood obesity has been the focus of considerable research, although the studies are of inconsistent quality. A meta-analysis of 88 studies (132) examined the association between soft drink consumption and weight gain, nutrition, and health outcomes. The analysis found associations of soft drink intake with increased energy intake and increased body weight. Soft drink intake also was associated with lower intakes of milk and calcium and with an increased risk of diabetes. Since not all studies of soda consumption have supported a role for soda in childhood obesity etiology, Vartanian and colleagues (132) attempted to explain the discordant results. They concluded that study design significantly influenced the results. Larger effect sizes were found in studies using a stronger experimental design (i.e., longitudinal and experimental studies). Studies of weaker design (i.e., cross-sectional or observational studies) were less likely to find an association. These workers concluded that population-based strategies to prevent childhood obesity by limiting soft drink consumption are “strongly supported” by the available scientific evidence of higher quality: 10 of 12 cross-sectional studies, all five longitudinal studies, and all four of the long-term experimental studies examined showed that energy intake rises when soft drink consumption increases (132). Another meta-analysis restricted to randomized controlled trials found that only 12 studies met the inclusion criteria. Of those, six showed a dose-dependent increase in weight when sugar-sweetened beverages were added to the diet. However, studies removing such beverages from the diet showed no significant effect on BMI. The authors concluded that, taken together, the data are inconclusive and that an adequately powered randomized controlled trial needs to be conducted in overweight persons since their analysis suggested evidence of an effect (133).

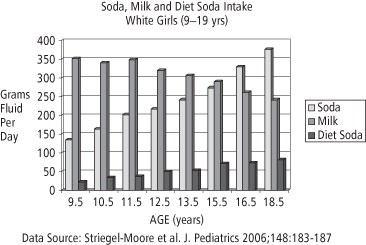

Nevertheless, the removal of soft drinks and other sugar-sweetened beverages from the diets of all children for the sake of obesity prevention may well be warranted for other reasons. The results of the Feeding Infants and Toddlers Study showed that sugar-sweetened beverages are fed to infants under the age of two, demonstrating that these beverages are now deeply embedded in US culture (76, 134), and raising the possibility that preferences for sweetened foods and beverages are being shaped during infancy (77–79). An analysis of beverage intake of children aged 9–19 years in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Growth and Health Study, conducted by Striegel-Moore and colleagues (135), illustrates that children are indeed drinking large quantities of sugar-sweetened beverages on a daily basis (see Figures 27-6 and 27-7).

Figure 27-6 Cross sectional data illustrating the changing patterns of intake of soda, milk and diet soda in white girls (ages 9 to 19)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree