Prevention of Psychiatric Disorders

David A. Mrazek

Patricia J. Mrazek

Introduction

The research evidence that supports preventive interventions has developed to a point that it is reasonable to establish public health goals that are designed to decrease the incidence of risk factors associated with the onset of mental illness. A number of malleable influences on child and adolescent development have been identified, and well validated preventive intervention programs are now being implemented.

However, preventive interventions have not been widely adopted, and even when psychiatrically ill children are

identified, many do not receive treatment. Given this context, it has been difficult to initiate preventive interventions for children who are only beginning to develop early symptoms that are associated with the onset of a psychiatric disorder. Furthermore, there is still insufficient political conviction that a public health investment in preventive interventions would result in a decrease in the prevalence and ultimately the cost of psychiatric illnesses.

identified, many do not receive treatment. Given this context, it has been difficult to initiate preventive interventions for children who are only beginning to develop early symptoms that are associated with the onset of a psychiatric disorder. Furthermore, there is still insufficient political conviction that a public health investment in preventive interventions would result in a decrease in the prevalence and ultimately the cost of psychiatric illnesses.

Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that it is possible to reduce the risk factors that are associated with mental illness. The majority of preventive trials have focused on the prenatal period, early infancy, childhood, and adolescence rather than on adulthood. Early studies have demonstrated that some positive outcomes have persisted for twenty years. More recently, the prevention of the initial onset of depression, anxiety, and psychosis has been demonstrated. The implementation of these interventions on a wider scale will hopefully provide convincing evidence that further validates that these interventions are effective.

Child and adolescent psychiatrists play critical roles in the initiation of clinical preventive interventions. This can occur as a consequence of their direct clinical care of children or their consultations to the community systems regarding the creation and improvement of prevention activities (1).

Research has begun to demonstrate that the prevention of mental disorders can be accomplished. This is an important development beyond earlier demonstrations of the prevention of behaviors that were linked with these disorders. Child and adolescent psychiatrists are in an ideal position to become more involved in these prevention research efforts given that they are the most intensively trained clinicians who routinely evaluate and treat severe mental illness in young patients. Importantly, psychiatric clinicians regularly work with psychiatrically ill children on a daily basis. Therefore, they are in key positions to identify and intervene with those children who are at highest risk. Preventive intervention research has benefited from interactions between academicians who are experts in research methodology and psychiatric practitioners who have extensive experience with children who are symptomatic and at risk for developing severe psychiatric illnesses.

History

In 1957, a series of definitions were put forward to organize the field of prevention of physical and emotional illnesses. Primary prevention was defined as an intervention designed to decrease the number of new cases of a disorder or illness. Secondary prevention was defined as an intervention designed to lower the rate of established cases of the disorder or illness. Tertiary prevention was defined as an intervention designed to decrease the amount of disability associated with existing illnesses. While all three of these “preventive” interventions are designed to have positive outcomes, only primary preventive interventions result in a decrease in the incidence of an illness in a given population at risk. In contrast, secondary and tertiary preventive interventions are initiated after the onset of the disorder and are better described as treatments designed to minimize the morbidity of already expressed diseases.

This older terminology was defined in Principles of Preventive Psychiatry, which was written in 1964 immediately following the mental health initiative that was advanced by the Kennedy administration (2). Ironically, despite this early recognition of the importance of prevention, child and adolescent psychiatrists have not played a central role in many of the more recently developed preventive intervention initiatives.

Development of Contemporary Definitions of Preventive Interventions

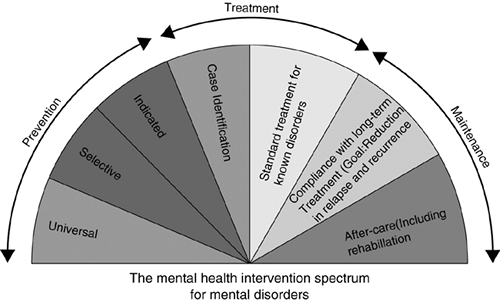

In the late 1980s a review of prevention research efforts at the National Institute of Mental Health suggested that more prevention research was needed. As a direct consequence of this recognition, an Institute of Medicine (IOM) committee on the prevention of mental disorders was created through a Congressional mandate. An important action of this IOM committee was to recommend the adoption of an alternative taxonomy for mental health interventions that more effectively differentiated prevention, treatment, and maintenance. The use of the term prevention in this classification system was restricted to interventions provided prior to a patient receiving a psychiatric diagnosis. The term treatment was reserved for therapeutic interventions provided to individuals who met diagnostic criteria. The term maintenance referred to long-term care provided to patients with chronic mental illness that reduced relapse and recurrence of symptoms and decreased the disability associated with the disorder (3). This classification system created a “spectrum of interventions” (Figure 2.2.2.1).

The IOM Committee recommended that three new subcategories of preventive interventions be formed in order to

better differentiate the wide variety of interventions that had previously been referred to as primary preventions. All three subcategories shared the defining characteristic that they were designed to be administered to populations prior to the initial onset of a psychiatric diagnosis. These categories were referred to as indicated, selective, and universal preventive interventions and were differentiated from each other based on their targeted populations. This nomenclature has become the standard method of describing preventive interventions (see Table 2.2.2.1).

better differentiate the wide variety of interventions that had previously been referred to as primary preventions. All three subcategories shared the defining characteristic that they were designed to be administered to populations prior to the initial onset of a psychiatric diagnosis. These categories were referred to as indicated, selective, and universal preventive interventions and were differentiated from each other based on their targeted populations. This nomenclature has become the standard method of describing preventive interventions (see Table 2.2.2.1).

TABLE 2.2.2.1 CLASSIFICATION OF PREVENTIVE INTERVENTIONS FOR MENTAL DISORDERS | |

|---|---|

|

Risk and Protective Factors

The term risk factor is used in both prevention and treatment, but the implications of risk within these two types of intervention are different. In prevention, a risk factor must predate the onset of the illness and can be a silent characteristic that is used to identify a target population. The reduction of risk factors that are both causal and malleable is a goal of preventive interventions. Once the diagnosis of an illness has been made, risk factors that are subsequently identified should be used to guide treatment decisions and influence the assessment of prognosis.

The concept of protective factors is parallel to risk factors. An individual who is characterized as having one or more protective factors is determined to be less at risk for the development of a specific form of psychopathology than an individual without the protective factor. The majority of protective factors are nonspecific and perceived to be universally beneficial. Common examples of protective factors include a supportive family environment or superior general intelligence.

While there is essentially a balance of positive protective factors and negative risk factors for every individual, there has not been a universally accepted methodology for the creation of an overall quantification of risk for a particular child. What may prove to be useful in the individual analysis of risk is to consider the relative weight of each identified risk and protective factor for a given individual. An analytic method with variably weighted coefficients recognizes that risk factors vary in their pathogenic effect. It also recognizes that biological and psychosocial risk factors as well as biological and psychosocial protective factors must be analyzed within the context of the developmental capacities of an individual child.

Prevention-Minded Treatment

In a very practical sense, child and adolescent psychiatrists have begun to expand their practices to include a modified form of treatment referred to as prevention-minded treatment (1). Prevention-minded treatment has been subdivided into two types. The first subtype of prevention-minded treatment involves the provision of traditional individual treatment, but includes strategies that are designed to indirectly benefit other family members. With this approach to prevention-minded treatment, the practitioner provides the direct treatment for the patient but considers the effects of his interventions on other family members who do not participate in the episode of care. The goal of this type of intervention is to provide indirect preventive interventions through the patient for another family member and it requires an appreciation of symptoms or exposure to risk factors of the other family member. An example of this approach is illustrated by the treatment of a mother with a major depressive disorder who has young children. If the clinician who is treating the mother becomes aware that her preschool child is developing behavioral symptoms such as an exaggerated concern for the safety of his mother, the clinician could bring these problems to the attention of her patient as well as providing her patient some guidance on how to handle these behaviors. Providing the mother a better understanding of the possible origins of the anxiety that her child is experiencing and providing the mother specific guidance in how to effectively reassure her child can be effective interventions. These interventions are designed to help both the mother and her child, but they would be a targeted preventive intervention for the child. Empirical evidence that effective treatment of major depressive disorders in women who have young children has a positive outcome not only on the women, but also on their children represents another example of indirect prevention-minded treatment (4).

The second type of prevention-minded treatment is a direct intervention involving other family members as a part of the treatment for the primary patient. This form of intervention often involves the invitation of other family members, including the children of a patient, to actively participate in therapy sessions. The therapist is open to the possibility of providing preventive interventions directly to other family members. Many forms of family therapy are designed to consider the adaptation of all members of the family system. An example could be an identified patient who is an adolescent with early prodromal symptoms of bipolar disorder whose family actively participates in family therapy. The ability of the teenager to monitor his own behavior may be severely compromised during hypomanic intervals. By recruiting family members to help the adolescent regulate his behavior, the anticipated escalation of these hypomanic symptoms may be averted. At the same time, this strategy can minimize the probability that the parents and siblings might develop symptoms. It does so by providing them with an intellectual context for dealing with the symptoms of bipolar illness and by preserving the quality of their interpersonal relationships.

Preventive Intervention Research

Preventive intervention research is a maturing scientific endeavor. The Society for Prevention Research is an interdisciplinary professional organization that is dedicated to promoting evidence-based programs and for increasing the quality of research projects in the field. The standards of evidence of the Society for Prevention Research for efficacy,

effectiveness, and dissemination of prevention programs and policies are now quite sophisticated (5). Specific issues related to the analysis of the outcomes of preventive intervention programs have been increasingly well addressed (6).

effectiveness, and dissemination of prevention programs and policies are now quite sophisticated (5). Specific issues related to the analysis of the outcomes of preventive intervention programs have been increasingly well addressed (6).

Many earlier preventive intervention research efforts did not designate presence or absence of psychiatric diagnosis as a primary outcome measure. However, preventive interventions focused on minimizing exposure to risk factors may well have an indirect positive benefit of preventing or delaying the onset of psychiatric disorders. The Prevention Research Program at the University of Arizona has demonstrated that preventive interventions can have multiple effects that improve function as well as reduce rates of psychiatric symptoms and psychiatric disorders (7). Their New Beginnings Program, a selective preventive intervention, targeted children whose parents had divorced. Approximately a third of the children of parents who divorce develop a psychiatric illness. Given this level of risk, these children are a very appropriate population for an early intervention. Using a randomized controlled clinical trial design, two well described preventive interventions were tested. The first intervention involved the mothers of the children and consisted of 11 group sessions and two individual sessions. The second intervention provided this same program for the mothers but also included 11 sessions for the children. The results of the six-year followup of both the program for the mothers and the program that involved both the mothers and children demonstrated that the children who received either of the interventions did better than the comparison group. The adolescents who had received these interventions were shown to have reduced symptoms of psychiatric disorder, lower rates of psychiatric diagnoses, less use of marijuana and alcohol, and fewer sexual partners. This program also resulted in parents having a greater sense of empowerment in their ability to be able to help their children. The consistency of these positive findings over multiple and varied outcome measures provides evidence to support the hypothesis that targeted preventive intervention efforts can simultaneously have broad beneficial effects and prevent psychiatric disorders. This program has addressed other important at-risk populations, including children who have experienced the death of a parent (8).

Prevention of Behavioral Disorders

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree