9 | Primary Osseous Tumors of the Cervical Spine |

| Case Presentation |

A 17-year-old male presented with vertebral plana at the cervicothoracic junction. He complained of pain and weakness. Physical examination showed bilateral triceps and intrinsic hand weakness. Plain radiographs showed vertebral plana, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated spinal cord compression from C7 to T2 (Fig. 9–1). The differential diagnosis included Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), Ewing sarcoma (EWS), lymphoma, aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC), metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma or neuroblastoma, and osteomyelitis. Staging studies did not reveal any evidence of metastatic disease. A core needle biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of EWS.

A multidisciplinary team of medical, musculoskeletal, and radiation oncologists administered corticosteroids and neoadjuvant multiagent chemotherapy. His neurological function improved immediately. The risks and benefits of surgical and nonsurgical options for definitive local control were discussed. The patient’s family desired to proceed with radiation therapy for definitive local control rather than an intralesional excision combined with radiation therapy or an en bloc spondylectomy.

Figure 9–1 A 17-year-old male with Ewing sarcoma involving C7 to T2. Vertebral plana is evident.

This case demonstrates the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to patients with primary bone tumors of the spine. The case also emphasizes the importance of obtaining diagnostic tissue prior to proceeding with a treatment plan even if the patient presents with neurological dysfunction. Vertebral plana is not diagnostic of LCH, and this case clearly demonstrates that a histological diagnosis is required to optimize treatment. This patient had a stable neurological examination; thus we obtained an urgent needle biopsy prior to administering corticosteroids, radiation, chemotherapy, or surgery. We administered corticosteroids after the biopsy to decrease the pain and compression associated with the tumor without compromising the quality of diagnostic tissue obtained, which can occur if corticosteroids are administered prior to the biopsy. Obtaining diagnostic tissue provides the multidisciplinary oncological team with invaluable information required to give appropriate recommendations.

| Background |

The treatment of benign1,2 and malignant3 primary osseous tumors of the cervical spine is diverse and complex. The clinical presentation and differential diagnosis must be considered prior to initiating treatment. Anatomical level (upper cervical, midcervical, cervicothoracic), location within the vertebra (body, pedicle, lamina), proximity to neurovascular and visceral structures, and histological diagnosis influence definitive treatment.

LCH is usually a self-limiting process that is often treated with observation or a percutaneous injection of corticosteroids. Multiple myeloma and lymphoma are usually managed with corticosteroids and chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy rather than operative intervention. Osteoblastoma, giant cell tumor (GCT), chondrosarcoma (CS), chordoma, and symptomatic osteoid osteoma, and osteochondroma are usually treated with surgical excision. ABC is often treated with an intralesional excision. However, embolization may be a more reasonable treatment for many patients with ABC. Osteogenic sarcoma (OGS) is usually treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and surgical excision.

A patient with a solitary cervical spine tumor and a stable neurological examination should obtain staging studies and a biopsy prior to proceeding with further intervention. Staging studies include laboratory studies (cell count, C-reactive protein, serum protein electrophoresis, prostate specific antigen); plain radiographs; a bone scan; a computed tomographic (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis; and a CT scan or MRI of the cervical spine.

A CT-guided core needle biopsy is the ideal method of obtaining diagnostic tissue. A large core needle biopsy usually provides diagnostic tissue without the potential destabilizing consequences of an open biopsy obtained through a laminectomy or corpectomy. A needle biopsy also minimizes contamination of surrounding tissue compared with an open biopsy. If diagnostic tissue is not obtained from the needle biopsy, then an open biopsy is warranted. A biopsy through a laminectomy minimizes contamination of visceral structures compared with a corpectomy and can function as the first stage of an en bloc spondylectomy, if deemed necessary. Needle and open biopsies must be carefully planned because a poorly executed biopsy can compromise oncological outcomes and treatment options. The biopsy should be guided by a practitioner with expertise in surgical oncology and spinal surgery. If the practitioner and institution cannot provide a definitive diagnosis and treatment, then the patient should be referred to a treatment center before performing the biopsy.4 Patients with multiple bony or visceral lesions probably have metastatic disease. The proper treatment of these patients is discussed in chapter 10.

A patient presenting with a progressive neurological deficit may require an emergent decompression and biopsy with frozen section analysis. Careful planning is required prior to performing the decompression to help minimize tumor contamination, which in turn stands to decrease the risk of local recurrence. The decompression and open biopsy are ideally performed by a surgeon with expertise in oncological and spinal surgery. A tumor in the lamina or spinous process is amenable to an excisional biopsy by means of a decompressive laminectomy.5 Tumors located primarily within the vertebral body can be initially treated with a decompressive laminectomy or a corpectomy. A laminectomy with a needle biopsy, as opposed to a corpectomy with an intralesional tumor excision and biopsy, reduces local tumor contamination of the anterior neck and can function as the first stage of an en bloc spondylectomy if warranted. However, a decompressive laminectomy alone removes the posterior tension band, which can render the spinal column more unstable. The patient is thus at risk for anterior column collapse and subsequent development of kyphosis and further neurological demise.6 The addition of provisional spinal instrumentation with or without a halo can provide temporary stabilization until the final histological diagnosis is made.

Corticosteroid administration should be considered for any patient with radiological evidence of spinal cord compression (SCC) and a progressive neurological deficit.7 However, a patient with a stable neurological examination should probably obtain a large-core needle biopsy prior to receiving corticosteroids because corticosteroids can have an oncolytic effect on myeloma, lymphoma, and LCH. This oncolytic effect decreases the likelihood of obtaining a diagnostic biopsy. Corticosteroids can be administered after diagnostic tissue is obtained.

Many primary bone tumors are best treated with an en bloc excision because the risk of local recurrence is probably lower for patients treated with an en bloc excision with adequate margins when compared with an intralesional excision.8–11 However, the proximity of the spinal cord, vertebral arteries, important functional nerve roots, and visceral structures makes en bloc excision extremely difficult in the cervical spine.

Tumors involving the lamina or spinous process can be completely excised by creating bilateral troughs in the lamina and removing the tumor en bloc. However, en bloc excision of a tumor involving the pedicle, transverse foramen, or vertebral body is demanding and requires extensive planning, preparation, and experience. Tumors involving both transverse foramina are probably best treated with an extracapsular intralesional excision rather than an en bloc excision. Odontoid lesions are nearly impossible to remove in one piece because the vertebral arteries, spinal cord, hard palate, and ligamentous structures impede en bloc removal of these tumors unless they only involve the caudal half of the odontoid or the unilateral aspect of the base of C2. Lower cervical tumors often involve unilateral or bilateral vertebral arteries and nerve roots to the phrenic nerve or brachial plexus. Cervicothoracic tumors are in close proximity to the vertebral arteries and the nerve roots that supply the intrinsic hand muscles. Various techniques for en bloc excision of upper12 and lower cervical11,13,14 and cervicothoracic tumors have been described. The proper treatment must consider the risk of neurological and vascular injury while preserving spinal stability and, if possible, spinal mobility. C5 to T1 nerve roots are usually spared during en bloc resections. Unilateral vertebral artery ligation does not usually cause ischemic injury of the brainstem, cerebellum, or spinal cord.15 However, tumor involvement of both vertebral arteries often precludes en bloc excision of the tumor, and a staged extracapsular intralesional excision can be performed with preservation of the vertebral arteries.16 Staged ligation of both vertebral arteries with or without vertebral artery bypass has been described, and can be considered in certain situations to enable complete excision of the tumor.14 A 30-minute vertebral artery occlusion test can help evaluate the patency of the right and left collateral circulation to the vertebrobasilar region. Tolerance of unilateral or bilateral vertebral artery occlusion clearly depends on collateral flow to the basilar trunk.14

Radiation therapy is not usually used to treat benign primary bone tumors because appropriate nonoperative and operative measures are usually curative, and the risk of developing radiation-associated malignancies, myelopathy, kyphotic deformity, and surrounding soft tissue and visceral damage is high relative to the potential benefit of decreasing the likelihood of local tumor recurrence.17 Additionally, most primary benign and malignant bone tumors are relatively radioresistant. However, EWS is relatively radiosensitive, and some patients with EWS are best treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radiation therapy for definitive local control.17 Almost all patients witty multiple myeloma or lymphoma are best treated with corticosteroids and chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy rather than surgery. Patients with OGS, chordoma, and CS are best treated with en bloc excision. However, radiation therapy is sometimes administered after inadvertent or planned tumor contamination16,17 to potentially eradicate residual microscopic tumor cells. Radiation therapy is generally more effective against microscopic disease, thus removal of all gross tumor is recommended.18–20 Proton beam radiation may provide better tumor control with less damage to surrounding soft tissues than conventional radiation therapy.

| Benign Primary Bone Tumors |

Aneurysmal Bone Cyst

ABCs are highly vascular lesions of unknown etiology. They represent ~1% of all primary bone tumors and commonly occur in the second decade of life. Females are affected more often than males. Primary ABCs are not associated with an underlying lesion, whereas secondary ABCs arise in conjunction with some primary bone tumors like GCT, chondroblastoma, osteoblastoma, and telangiectatic OGS. Approximately 10 to 20% arise from the mobile spine, with ~10% of these tumors affecting the cervical spine. Common clinical symptoms and signs include pain and swelling. Neurological deficits are present in ~25% of patients. The posterior elements are almost always involved. Cavernous spaces containing red blood cells are commonly seen on histological examination. Plain radiographs and CT usually demonstrate a lytic, expansile lesion. MRI often shows fluid-fluid levels, which are pathognomonic. Intralesional excision, en bloc excision, and selective arterial embolization have been successfully used, alone or in combination, by different authors.21–23 The incidence of local recurrence is -10% after intralesional excision. Malignant transformation of ABCs has been described in patients previously treated with irradiation.21 Radiation therapy is thus not usually recommended for these patients.

| Authors’ Preferred Management |

Selective arterial embolization should be considered for patients with a physiologically stable spine.23 Patients with progressive neurological deficits, progressive or unacceptable deformity, or intractable pain may benefit from surgery. A patient with a physiologically unstable spine with a tumor involving the lamina or spinous process are treated with en bloc excision with or without spinal stabilization, whereas those with vertebral body or pedicle involvement can be treated with preoperative embolization followed by an intralesional excision, stabilization, and fusion.

Giant Cell Tumor

GCTs are tumors composed of multinucleated osteoclast-like giant cells and mononuclear cells. They represent ~5% of all primary bone tumors and commonly occur in the third decade of life. Females are more affected than males. Approximately 5% of these tumors arise from the mobile spine, with ~30% of these tumors affecting the cervical spine. Pain is almost always present, and radiculopathy is common. GCTs are usually lytic and arise from within the vertebral body. Intralesional extracapsular or en bloc excision is the treatment of choice.14,24 Hart et al reported a lower incidence of local recurrence for patients treated exclusively at a tertiary care center compared with patients treated elsewhere before referral (18% vs 83%).24 Interestingly, this group also noted that none of the patients in Italy had prior treatment other than a biopsy prior to referral compared with 29% (6/21) of patients treated in American centers. Serial selective arterial embolization,24–26 and interferon27,28 may prove to be useful adjuncts to help decrease the likelihood of local recurrence or treat unresectable tumors. Radiation therapy is associated with the development of postradiation sarcoma and is not recommended for most patients with a GCT.24,29 Preoperative embolization can reduce blood loss associated with excision of a GCT.

| Authors’ Preferred Management |

Preoperative embolization with an intralesional extracapsular excision at a tertiary care center is probably the most appropriate treatment of patients with a GCT involving the cervical spine. Removal of all gross tumor, including the pseudocapsule combined with minimal soft tissue tumor contamination of the surrounding tissue, is recommended. En bloc excision is not usually recommended for GCT involving the cervical spine because of the associated morbidity and complexity of an en bloc excision in the cervical spine for a tumor that can usually be well controlled with an intralesional, extracapsular excision. En bloc excision should be considered for GCTs that do not involve the transverse foramen or for recurrent GCTs.

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

LCH, which was previously called histiocytosis X or eosinophilic granuloma, is a tumor composed of mononuclear cells called Langerhans histiocytes. LCH is a focal or multifocal benign proliferation of Langerhans histiocytes in the skeletal system. Ten to 20% of patients with skeletal involvement of LCH will have lesions in the spine, with the cervical spine involved in ~15% of these patients. LCH usually occurs in the first or second decade of life. Neurological symptoms are rare and are usually limited to mild paresthesias or radicular pain. Early lesions are usually lytic, whereas vertebra plana is a common late finding. Histological examination reveals Langerhans histiocytes, which contain a coffee bean-shaped nucleus. Eosinophils are often present. These lesions are usually self-limiting and surgery is rarely required. Treatment recommendations include observation,30–32 oral or intralesional corticosteroids,33 chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. There is controversy regarding the need to biopsy solitary, cervical spine lesions with vertebral plana. Some authors recommend close clinical observation,34 whereas others recommend a biopsy. We believe that obtaining diagnostic tissue is warranted because the differential diagnosis of a destructive cervical spine lesion with or without vertebral plana or a soft tissue mass includes LCH, osteomyelitis, EWS, metastatic carcinoma, lymphoma, ABC, acute leukemia, metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma or neuroblastoma, and plasmacytoma. Cultures should be obtained at the time of biopsy.

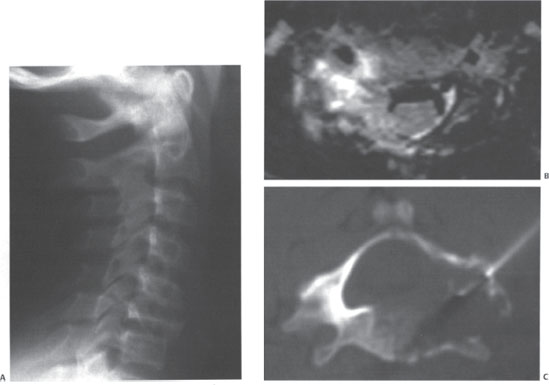

Figure 9–2 (A) A 10-year-old male with C6 vertebral plana. (B) T2-weighted axial magnetic resonance imaging with an expansile vertebral lesion surrounding the vertebral foramen and compressing the thecal sac. (C) Computed tomographically guided needle biopsy of the vertebral lesion demonstrated Langerhans cell histiocytes on cytological examination. An intralesional injection of corticosteroids was administered.