Atrophy maps in PPA subtypes [7, 11]. Only the left hemisphere is shown. Areas in red and yellow show peak atrophy sites when patient groups of a given subtype were compared to 27 age-matched controls using FreeSurfer software [7]. Abbreviations: ATL: anterior temporal lobe, IFG: inferior frontal gyrus, PPA-G, PPA-L, PPA-M, PPA-S: agrammatic, logopenic, mixed, and semantic variants of primary progressive aphasia.

The logopenic subtype (PPA-L) is characterized by variable interruptions of fluency on a background of intact grammar and comprehension. The patient may appear fluent if allowed to engage in small talk and generalities but starts to display frequent word-finding hesitations when access to specific terms and infrequently used words becomes necessary. Many patients will circumvent these retrieval blocks through circumlocutions but a careful listener will detect a pervasive simplification of output. Object naming impairments (anomia), based on word retrieval failures, are usually present and may elicit phonological paraphasias. Abnormal repetition has been included as a necessary criterion for the research-based diagnosis of this subtype [10]. However, this feature can be so mild that its inclusion as a core criterion may need to be reconsidered [7, 11]. The distinctive anatomical pattern in PPA-L is one where the atrophy is much more pronounced in the posterior than anterior parts of the language network. Peak atrophy sites include posterior temporal cortex and the temporoparietal junction where the inferior parietal lobule abuts the posterior parts of the superior and middle temporal gyri.

The core features of the semantic subtype (PPA-S) include profound impairments of object naming and word comprehension on a background of preserved fluency, repetition, and grammar. Initially, the relatively preserved comprehension of conversation (in part due to the patient’s ability to catch contextual cues) contrasts sharply with severe deficits in understanding nouns that denote concrete entities, especially animals, fruits, and vegetables. Initial comprehension and naming impairments display the phenomenon of taxonomic interference whereby words are understood at a generic but not specific level of meaning [12]. An analogous impairment at the stage of translating percepts and thoughts into words leads to the semantic paraphasias and vagueness of speech content. As the disease progresses, the comprehension impairment extends to all word classes and sentences. Surface dyslexia and dysgraphia (inability to read or spell words that have irregular phonology) are commonly seen. The distinctive peak atrophy sites in PPA-S are concentrated within the anterior temporal lobe (ATL) of the left hemisphere.

In a few PPA patients, combined impairments of grammar and comprehension arise early in the course of the disease. These patients constitute a fourth group of “mixed” PPA (PPA-M) [7, 11]. Peak atrophy sites in these patients include the IFG as well as the ATL of the language-dominant hemisphere (Figure 10.1).

Classification systems

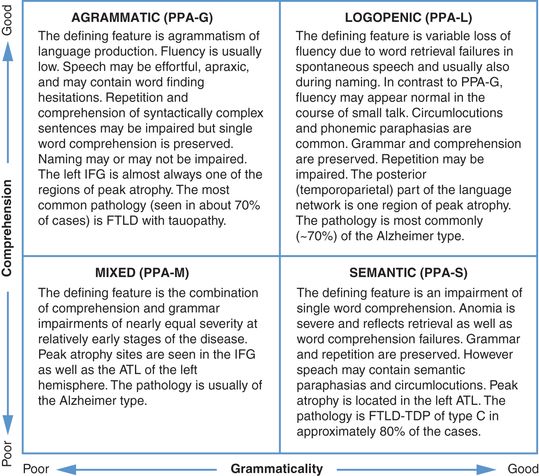

Consensus guidelines for subtyping PPA have been compiled [10]. They are based on principles of neurolingusitics and have systematized the classification of patients with this syndrome for research purpose. In their present version, however, the guidelines do not account for all language impairment patterns of PPA and allow some patients to fulfill criteria for more than one subtype. Minor revisions to correct these problems are being considered [13]. The consensus guidelines also require the assessment of ten different domains of language function. Their routine implementation in clinical settings would be burdensome. A simpler, albeit less rigorous, alternative is to use the two-dimensional template based on word-comprehension and grammar function as shown in Figure 10.2.

A two-dimensional template for the rapid clinical classification of PPA patients. The choice of tests and of cut-off scores needs to be determined empirically.

The upper left and lower right quadrants of this template closely correspond to the PPA-G and PPA-S subtypes delineated by the 2011 consensus guidelines. The lower left quadrant incorporates the PPA-M patients, a subtype that is not part of the 2011 guidelines. The upper right quadrant is the most heterogeneous. It contains not only the PPA-L subtype as defined by the 2011 guidelines (i.e., combination of word retrieval and repetition impairments), but also patients who are descriptively logopenic (i.e., have word retrieval impairments) but without abnormalities of repetition. The template approach is most meaningful if it is used within 1–3 years after symptom onset. If it is used too early in the disease, the upper right quadrant will contain patients in the prodromal stages of PPA-G and PPA-S; if it is used at advanced stages, many patients will have developed language production as well as comprehension impairments and will gravitate toward the lower left quadrant. The progressive nature of the language impairment introduces additional layers of complexity to the classification of PPA.

Trajectory of progression

Gradual intensification of impairment is the hallmark of PPA [5, 14, 15]. Each clinical subtype displays a somewhat different progression trajectory. In PPA-S, the extension of ATL atrophy into the anterior insula, posterior orbitofrontal cortex, and contralateral ATL may lead to the emergence of behavioral abnormalities characteristic of FTD syndromes or associative agnosia characteristic of the semantic dementia syndrome. In PPA-G, the spread of atrophy to motor areas and basal ganglia may lead to the emergence of movement disorders characteristic of the corticobasal degeneration or progressive supranuclear palsy syndromes. The trajectory of PPA-L is the most variable. In some patients, additional IFG atrophy leads to the emergence of features characteristic of PPA-G. In others, the spread of atrophy into additional parts of the temporal lobe leads to word comprehension and memory impairments. Some cases of PPA-L can show an unusually indolent pace of progression for up to a decade or more during which daily living activities that do not depend on language are maintained.

Neuropathology and differential diagnosis

The PPA syndrome can be caused by Alzheimer pathology or frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD). The two major classes of FTLD most relevant to PPA are designated FTLD-tau and FTLD-TDP [16]. In FTLD-tau the abnormal protein is a hyperphosphorylated and misfolded form of tau with morphologic and molecular features that are different from the neurofibrillary tauopathy of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). In FTLD-TDP the pathology revolves around abnormal precipitates of the 43 kd transactive response DNA-binding protein TDP-43. Major FTLD-tau subtypes include Pick’s disease (PiD), tauopathy of the corticobasal degeneration (CBD)-type, and tauopathy of the progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP)-type, each identified according to the molecular forms and morphology of the hyperphosphorylated tau precipitates. FTLD-TDP is further subdivided into types A, B, C, and D depending on the distribution of the abnormal TDP-43 precipitates.

According to multiple autopsy series, approximately 30% of PPA patients are found to have the neuropathology of FTLD-tau while an additional 30% have FTLD-TDP. The remaining 40% of patients display Alzheimer pathology but with neurofibrillary degeneration that is usually more intense in the language-dominant hemisphere [17–21]. Rarely, PPA can be caused by diffuse Lewy body disease (DLBD) [21]. Although Jacob–Creutzfeldt disease can also lead to PPA, the course is usually much faster and inconsistent with the temporal course of a neurodegenerative process [22]. This heterogeneity shows that the clinical specificity of the PPA syndrome is not determined by the histopathology of the disease but, rather, by its anatomical predilection for the language network of the brain.

Accurate clinical classification of PPA increases the precision with which the clinician can predict the nature of the underlying pathology. In PPA-S, approximately 70% of patients will be found at autopsy to have FTLD-TDP pathology of type C [23, 24]. Approximately 60–70% of PPA-G patients have FTLD-tau with the remainder having Alzheimer pathology or FTLD-TDP of type A. The pattern is different in PPA-L where approximately 60% of patients have Alzheimer pathology and the remainder FTLD-T or FTLD-TDP of type A [21].

At the individual patient level, no PPA subtype is pathognomonic for a specific type of neuropathology. Within the same PPA subtype patients with and without Alzheimer pathology are nearly indistinguishable: they both have asymmetric atrophy, progressive aphasia, and relative preservation of memory for recent events. The question of differential diagnosis in these patients can be addressed with the help of biomarkers such as amyloid imaging and determinations of tau and beta-amyloid in the CSF. A positive amyloid PET scan or high phosphotau with low beta-amyloid in the CSF signals a very high likelihood of Alzheimer pathology while a negative amyloid scan with normal CSF beta-amyloid and phosphotau excludes Alzheimer pathology with a great deal of certainty. In the future, tau imaging with PET will help to differentiate FTLD-tau from FTLD-TDP. Patients will frequently ask whether the diagnosis is “PPA or AD.” The clinician needs to state that it could be both, and then explain that in this context the term “PPA” refers to the clinical features experienced by the patient while the term “Alzheimer” refers to the nature of the microscopic changes that damage the language-related parts of the brain.

Patient care

Patient care in PPA can be divided into symptomatic and etiological components. The symptomatic approach starts with an evaluation by a knowledgeable speech therapist who can work with the patient and family to maximize communicative effectiveness and who can also assess the potential usefulness of assistive software and hardware. The etiological component of patient care revolves around the judicious use of clinical subtyping and biomarker information to surmise the nature of the underlying disease process. Based on this information, the clinician can decide whether to use Alzheimer medications or to channel the patient into clinical trials relevant to Alzheimer’s disease or FTLD.

For several years following symptom onset, the non-dominant hemisphere may show no significant atrophy or loss of metabolism [25]. Even within the affected hemisphere atrophic components of the language network continue to participate, albeit inefficiently, in the performance of language tasks [26]. The question has therefore been raised whether activation of either hemisphere with transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) might prove beneficial. Anecdotal reports have described positive results [27].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree