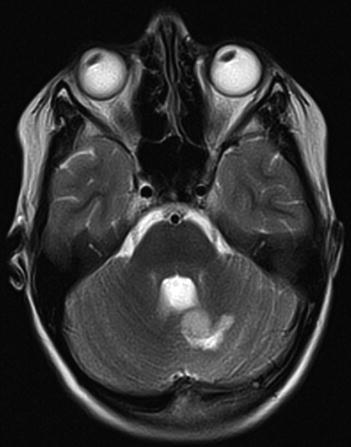

Fig. 6.1

The preoperative MRI

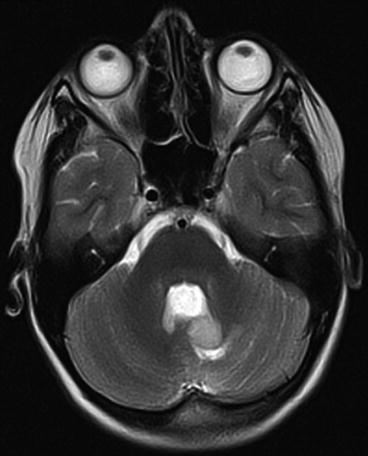

Fig. 6.2

The postoperative MRI at 7 months

Fig. 6.3

The postoperative MRI at 12 months

Case 4 (Patient Shares Criminal Intent with the Psychiatrist)

A paranoid patient tells his psychiatrist he is going to murder his wife. The psychiatrist deems the threat idle and does not take action (i.e., informing the police or forcing a hospital admission of the patient). The patient actually tries to kill his wife and harms her severely. What would have been the wisest thing to do?

Case 5 (Lack of Privacy in the Surgeon’s Waiting Room)

A man accompanies his wife for a consultation with the neurosurgeon about spinal stenosis. In the waiting room, he hears the secretary call out, “Mr. Bob Smith, Dr. Cushing will see you now.” He looks over to see that the man is the same Bob Smith who works under him at the office and is currently up for a promotion. He also recognizes Dr. Cushing’s name as a leading malignant brain tumor surgeon and wonders whether Smith’s recent promotion at work should perhaps be reconsidered.

6.3 Approach to the Cases

The first case is an example of a breach in privacy of the patient with no benefit to anyone but just harm, an egregious violation of the patient’s autonomy.

In the second case, confidentiality is demanded from the physician, which brings him into an awkward situation concerning his colleague. If he violates the family’s request and speaks to the first surgeon, there are no disadvantages to the patient so the violation might be justifiable.

In the third case, there is a conflict between the patient’s universal, ethical right to autonomy, the legal local law, and the physician’s personal decision, which derives from beneficence. To withhold the information from the boy and consequently limit his autonomy holds a great risk of maleficence. The son has the right to autonomy, being a bright young boy with the capacity to understand his situation and the consequences. Due to the legislation in his country, his mother has parental responsibility as well as the parental right to determine the course of treatment, although most Western societies recognize that there is no definitive age cutoff for determining competence and a mature 12-year-old might be deemed competent by the surgeon. The surgeon knows the tumor will require repeat surgery and/or radiation, so by following the mother’s will, harm will be done to the boy.

In the fourth case, the patient’s confidentiality is respected, but harm was done to a third party, which could have been prevented if dealt with differently. This case illustrates a clash between utilitarian ethics (do what produces the best outcome for the most people) and Kantian deontology (do what is deemed right irrespective of the consequences).

In the fifth case, imperfect systems have led to the disclosure of information about a patient to someone who can use this information in a way which may hurt the patient. The case highlights how much improvement is needed in everyday systems in our hospitals.

6.4 Discussion

6.4.1 Definition of Privacy and Confidentiality

The distinction between patient’s privacy and a patient’s confidentiality can be murky (Higgins 1989; Kleinman et al. 1997; Thompson 1979). In law, privacy has been described as “the right to be left alone.” A broad but fitting description of the difference between both is that privacy relates to a person and confidentiality relates to the information and data about an individual. The distinction is not that important as practically speaking, there is a great overlap between privacy and confidentiality.

In medical practice, privacy is probably best described as the right of the patient to have his/her person and information kept confidential, as well as the right to transfer this information in confidential surroundings. For example, physical examinations are conducted in a closed room. During rounds on the ward, family members and friends are requested to leave temporarily. Results of medical examinations and treatment plans are discussed in a private area.

A patient’s confidentiality is the right of the patient to nondisclosure of his/her information and data. This concerns verbally transferred information of the patient, as well as the security of the documented information, written or, nowadays ever more often, digital files. Exceptions are made when information is required by law, in the public interest. Clinical everyday examples are computers which are encrypted and have multiple password protection of patient files, and the storage of hard copies of patient files in separate, lockable spaces, not in open sight on counters or desks.

Pearl

Privacy is the right of the patient to transfer his/her personal information in a confidential surrounding, and confidentiality is the right of the patient to nondisclosure of his/her documentary information.

6.4.2 Privacy in Daily Clinical Life

The privacy of patients applies to many situations and is essentially an ever-present concern to the patient and to healthcare providers. The lack of privacy starts in the neurosurgery clinic waiting room. If ten patients are waiting in a common waiting room at any given time of the day, it is entirely possible that privacy could be lost by one patient recognizing another or one patient or family member recognizing a public figure or someone in their work life. Some corrective measures can be taken. Most psychiatrists have offices with separate entrance and exit doors so no two patients ever come face to face. Medical history-taking and physical examination should always take place in a private room with a door, although in many parts of the word, especially resource-poor settings, two or three patients often share one examining room. The patients’ hard copy files should be kept in a separate room where only limited people have access and should even be stored in a space, which can be locked, to ensure the utmost possible privacy. To follow these guidelines is unfortunately not always possible, due to the ever more limited time we have for the growing workload and logistic issues like limitations of space.

Modern systems provide the possibility to have a digital patient file. Even without a patient file, many patients’ data are accessible online in a hospital. The digitizing of the patients’ data facilitates our work and under the contemporary progressive strain in healthcare it saves time. At the same time, it is a liability concerning the patient’s privacy, because all digital data can be accessed both inadvertently and maliciously (i.e., hacking).

Conversations about patients between colleagues are often held in the hallway or elevators and can easily be overheard unnoticed – these behaviors should be avoided.

Pearl

Patient data should be kept confined in a safe space as much as possible. Conversations about patients should be held behind closed doors. Healthcare providers must always be aware of the public place they are in.

6.4.3 Confidentiality in Daily Clinical Life

Not to disclose the patient’s information seems a straightforward rule, even when one takes into account the exceptions, when disclosure is demanded for the public good or by law. Still, breaching confidentiality occurs more often than we think. Most of the time, we do not talk to the patient openly about whom we may disclose his/her medical information to, but it is understood that whenever we talk of a patient’s condition, consent is implicit (e.g., speaking to the patient’s spouse) or we must obtain verbal or written consent to do so. Confidentiality of patient data has become more complex and problematic as the medical profession progresses closer toward electronic records, which are subject to many abuses, both accidental and intentional (Graves 2013).

A very common example is when a neurosurgeon is called on the phone or e-mailed by a distressed, unknown family member of a recently operated patient inquiring about the condition of the patient (Weiss 2004). Most clinicians are trusting empathetic people, and we generally trust that the person is who they say they are and we provide some general information without checking the identity of the caller. If we do this, which is strictly speaking ill-advised, we should at minimum inform the patient as soon as possible of the conversation. Sometimes, sharing information can be very problematic in, for example, a situation where there is marital discord and a girlfriend presents herself as the person to communicate with, as opposed to the patient’s legal wife. In these situations, the surgeon must be extremely careful not only to protect the patient but also to protect himself/herself. As long as no harm is done to the patient, his/her confidentiality must be categorically and unconditionally respected.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree