Progression and Surgical Management of Isthmic Spondylolisthesis in Adults

Yizhar Floman

Although isthmic spondylolisthesis is often referred to as a congenital anomaly, it is well documented that spondylolysis usually evolves long after birth; between the ages of 5 and 8 years, and that the development of spondylolisthesis may begin up to the age of 20 years (1). Spondylolisthesis is present in about 6% of the population aged 20 years (2). A stress or a fatigue fracture through the pars interarticularis is probably the basic lesion leading to the development of isthmic spondylolisthesis (3). Despite the fact that the condition usually originates before adulthood, only 23% of children and adolescents are symptomatic; among the 23% are especially those with high-grade slips (4). Many adults are unaware of their spondylolisthesis until the fourth or fifth decade of life (5). If spondylolisthesis is a lesion that characteristically develops in late childhood or adolescence and seldom after the age of 20 years, why is this lesion clinically silent in early adulthood, and why does it become symptomatic after the third or fourth decade? What is the mechanism that leads this dormant lesion in the lumbar spine to manifest itself, and what is the best surgical solution for symptomatic adult isthmic spondylolisthesis? These questions will be addressed throughout the following chapter.

The intervertebral disc and the posterior elements, including the facet joints and the spinal ligaments, all play an important role in stabilizing the spinal motion segment. The facet joints determine the direction of movement of the spinal motion segment, whereas the intervertebral disc determines the extent of motion. Anterior translatory motion is mainly resisted by the paired facet joints, the pars interarticularis, and the intervertebral disc (6). The vertical sum of the forces affecting the spine results in 80% anterior column compression and 20% anteriorly directed shear forces (7).

In the presence of a bilateral pars interarticularis defect, spondylolisthesis occurs as a result of anterior shear forces acting parallel to the disc space at the slip level. There are higher anterior shear forces at the lumbosacral junction due to the obliquity of the L5-S1 disc. Because of the pars defect, the facet joints are no longer able to resist the anterior shear forces, and the intervertebral disc becomes the main structure resisting these forces and maintaining the stability of the spinal motion segment. As long as the disc retains its normal biochemical and biomechanical properties, the spinal motion segment will remain stable, despite the presence of mild slip and the loss of the resistance to anterior shear forces that is normally provided by the facet joints.

Although Friberg (8) contended that adult isthmic spondylolisthesis is hypermobile and unstable, several in-vivo radiologic studies have demonstrated Grade 1 to 2 isthmic lumbosacral spondylolisthesis in adults as being stable (9,10,11). Penning and Blickmann (9) studied sagittal plain motion in 24 individuals with lumbosacral spondylolisthesis who underwent radiography in various positions. No abnormal sagittal translatory motion

at the lumbosacral level was detected in any of the x-rays taken. Pearcy and Shepherd (10) used biplanar radiography to study symptomatic patients with Grade 1 to 2 lumbosacral olisthesis and found decreased motion at the lumbosacral level in flexion, extension, lateral bending, and axial rotation as well as in coupled motions. They detected no forward or backward translation greater than 2 mm; they also noted that translation in persons with symptomatic lumbosacral olisthesis was not larger than translation occurring in a healthy control group. The only significant difference between olisthetic individuals and controls was a decrease in flexion and extension at the lumbosacral level. Pearcy and Shepherd (10) therefore questioned the contention that mild adult lumbosacral spondylolisthesis is mechanically unstable. However, they could not rule out the role of muscle splinting in providing mechanical stability to the lumbosacral slip. More recently, Axelsson et al. (11) studied adult patients with mild spondylolisthesis and matched controls by means of roentgen stereophotogrammetry, which is the most accurate radiographic method currently available for measuring intervertebral motion. They failed to find any difference in the sagittal or vertical axis motion between the spondylolisthetic individuals and the controls. The transverse translatory motion was negligible in both groups (11). Thus, three independent radiographic investigations attested to the stability of adult low-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis (9,10,11).

at the lumbosacral level was detected in any of the x-rays taken. Pearcy and Shepherd (10) used biplanar radiography to study symptomatic patients with Grade 1 to 2 lumbosacral olisthesis and found decreased motion at the lumbosacral level in flexion, extension, lateral bending, and axial rotation as well as in coupled motions. They detected no forward or backward translation greater than 2 mm; they also noted that translation in persons with symptomatic lumbosacral olisthesis was not larger than translation occurring in a healthy control group. The only significant difference between olisthetic individuals and controls was a decrease in flexion and extension at the lumbosacral level. Pearcy and Shepherd (10) therefore questioned the contention that mild adult lumbosacral spondylolisthesis is mechanically unstable. However, they could not rule out the role of muscle splinting in providing mechanical stability to the lumbosacral slip. More recently, Axelsson et al. (11) studied adult patients with mild spondylolisthesis and matched controls by means of roentgen stereophotogrammetry, which is the most accurate radiographic method currently available for measuring intervertebral motion. They failed to find any difference in the sagittal or vertical axis motion between the spondylolisthetic individuals and the controls. The transverse translatory motion was negligible in both groups (11). Thus, three independent radiographic investigations attested to the stability of adult low-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis (9,10,11).

The fate of mild isthmic spondylolisthesis in individuals who sustain major trauma to the lumbar spine may also attest to the stability of this lesion. Since isthmic lumbosacral slip occurs in about 6% of the population, it is not uncommon for some of these individuals to sustain a traumatic lumbar vertebral fracture. The incidental occurrence of lumbar spine fractures in individuals with preexisting mild lumbosacral slip may be considered as being a simulated in-vivo biomechanical experiment that tests the stability of lumbosacral spondylolisthesis. Seven such cases were retrieved among 300 patients with thoracolumbar spine fractures who were managed during a 10-year period at one institution (12). All seven patients had a Grade 1 spondylolisthesis; five had sustained a lumbar burst fracture, and two had a lumbar compression fracture. The lumbosacral slip in all of them was judged to be old, preexisting the lumbar fracture, as evidenced either by a positive previous history of a slip, by dating the lesion with a 99 m-Tc-MDP bone scan, or by operative findings at the slip level. No evidence was found in any of these seven cases to indicate that the lumbosacral slip was affected by the major lumbar trauma. These cases serve to illustrate that a lumbosacral spondylolisthesis can absorb vertical compression forces as well as considerable anterior shear forces without demonstrable evidence of damage. This in-vivo “experiment” sheds some light on the biomechanics of mild lumbosacral olisthesis and lends support to the notion that mild olisthesis is mechanically stable.

What then are the sources of back and leg pain in adults with mild or moderate lumbosacral spondylolisthesis? Symptoms are usually the results of disc degeneration or herniation above the slip level, or a result of disc degeneration at the slip level (i.e., the lumbosacral level). It is reasonable to assume that the integrity of the disc at the slip level plays a key role in the stability of the lumbosacral articulation in the presence of a bilateral pars defect. As long as this disc maintains its structural and functional integrity, the lumbosacral articulation will be stable and will not generate painful stimuli, while its degeneration will eventually lead to adult slip progression. As the slip increases, anterior shear forces will increase as well, leading to further disc degeneration and further slip progression. Slip progression generates painful stimuli of instability and associated spinal stenosis (5).

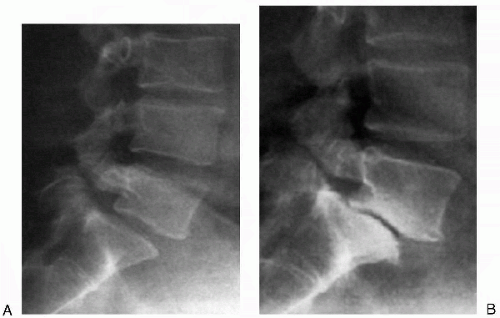

Until recently, there has been little mention in the literature of progression of lumbosacral spondylolisthesis in adults (5). On the contrary, while slip progression before

skeletal maturity has been adequately recorded, its occurrence in adults has been questioned (13,14,15). Slip progression in adults does occur, however (Figs. 26.1 and 26.2). Floman (5) reported on the progression of isthmic spondylolisthesis after skeletal maturity in 21 patients between the ages of 32 and 60 years. Documented slip progression ranged between 8% and 30% and occurred over a period of 3 to 20 years. In most cases, slip progression started after the age of 30 years. The increased olisthesis was always associated with degenerative disc disease at the slip level. Disc degeneration increased anterior shear forces, giving rise to increased olisthesis. Unlike lumbosacral adult slip

progression, progression of L4-L5 isthmic olisthesis in adult life is better documented in the literature (15).

skeletal maturity has been adequately recorded, its occurrence in adults has been questioned (13,14,15). Slip progression in adults does occur, however (Figs. 26.1 and 26.2). Floman (5) reported on the progression of isthmic spondylolisthesis after skeletal maturity in 21 patients between the ages of 32 and 60 years. Documented slip progression ranged between 8% and 30% and occurred over a period of 3 to 20 years. In most cases, slip progression started after the age of 30 years. The increased olisthesis was always associated with degenerative disc disease at the slip level. Disc degeneration increased anterior shear forces, giving rise to increased olisthesis. Unlike lumbosacral adult slip

progression, progression of L4-L5 isthmic olisthesis in adult life is better documented in the literature (15).

Ample evidence in the literature suggests that disc degeneration is the key to converting a stable spondylolisthesis into an unstable, progressing slip. The classical teaching was that disc degeneration and herniation occur at the level above the slip (16). It was Farafan et al. (17) who correctly stressed that disc degeneration below the pars defect occurred as a result of rotatory and anteriorly directed shear forces. Disc degeneration at the slip level may start as early as adolescence (18). Sarasta (19) found that spondylolisthesis was associated with disc degeneration, especially after the age of 40 years and that slip increase was associated with disc degeneration. Fredrickson et al. (20) as well as Danielson et al. (21) conducted research on long-term follow-up of spondylolisthesis and concluded that the disc had an important role in buffering the instability imposed by the anterior shear forces and the pars defect.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree