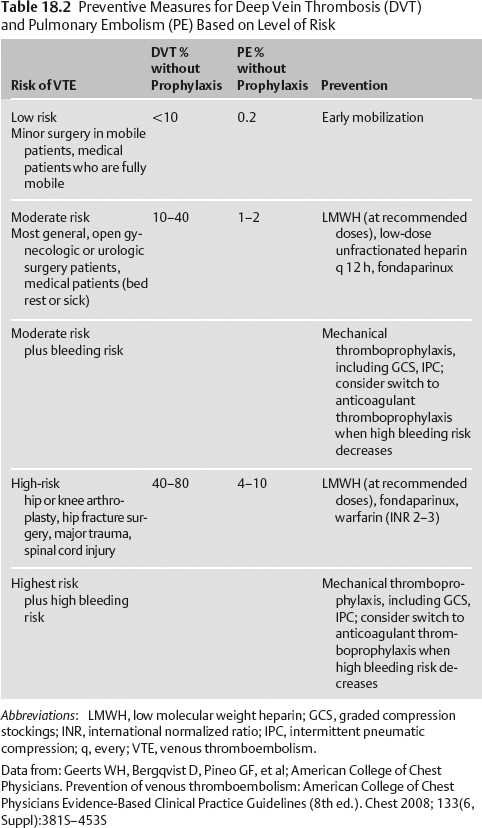

18 Prophylaxis Sherry Hsiang-Yi Chou Critically ill neurologic patients are at high risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE), nosocomial infection, gastric ulcer, and anemia. Prophylaxis can minimize the risk of these hospital complications. Pulmonary emboli (PE) account for 10% of hospital deaths and carry an in-hospital case fatality rate of 10% and a 1-year fatality rate of 30%. PE is the most preventable cause of in-hospital death. The risk for VTE depends on the patient’s age, history of hypercoagulability, prior VTE, history of cancer, and type of surgery (if any) Table 18.2.1 Data from: Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th ed.). Chest 2008; 133(6, Suppl):381S-453S Assess for history of cancer, hypercoagulability, previous VTE, coagulopathy, past GI bleed, anemia, steroid or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) use, and immunosuppressed state. Assess timing and type of surgery performed (if any). Evidence-based guidelines for preventing hospital complications are often “bundled” to allow for most effective implementation. Many government (Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations [JCAHO]) and state organizations support such bundles. Abbreviations: ACCP, American College of Chest Physicians; AHA/ASA, American Heart Association/American Stroke Association; b.i.d., twice a day; CT, computed tomography; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; GCS, Graded Compression Stocking; GBM, glioblastoma multiforme; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; IVC, inferior vena cava; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PE, pulmonary embolism; SCI, spinal cord injury; SQ, subcutaneus; t.i.d., three times a day; VTE, venous thromboembolism. Data from: Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th ed.). Chest 2008; 133(6, Suppl):381S-453S. Agnelli G, Piovella F, Buoncristiani P, et al. Enoxaparin plus compression stockings compared with compression stockings alone in the prevention of venous thromboembolism after elective neurosurgery. N Engl J Med 1998;339(2):80–85. Broderick J, Connolly S, Feldmann E, et al; American Heart Association. American Stroke Association Stroke Council; High Blood Pressure Research Council; Quality of Care and Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage in adults: 2007 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, High Blood Pressure Research Council, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Stroke 2007;38(6):2001–2023. Data from (continued): Spinal Cord Injury Thromboprophylaxis Investigators. Prevention of venous thromboembolism in the acute treatment phase after spinal cord injury: a randomized, multicenter trial comparing low-dose heparin plus intermittent pneumatic compression with enoxaparin. J Trauma 2003;54(6):1116–1124. Boeer A, Voth E, Henze T, Prange HW. Early heparin therapy in patients with spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1991;54(5):466–467. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2007;24(Suppl 1):S1-S106. Adams HP Jr, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, et al; American Heart Association. American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Clinical Cardiology Council; Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council; Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke 2007;38(5):1655–1711. Sherman DG, Albers GW, Bladin C, et al. PREVAIL Investigators. The efficacy and safety of enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after acute ischaemic stroke (PREVAIL Study): an open-label randomised comparison. Lancet 2007;369(9570):1347–1355. Sawaya R, Zuccarello M, Elkalliny M, Nishiyama H. Postoperative venous thromboembolism and brain tumors: Part i. Clinical profile. J Neurooncol. 1992;14:119–125. Sawaya R, Glas-Greenwalt P. Postoperative venous thromboembolism and brain tumors: Part ii. Hemostatic profile. J Neurooncol. 1992;14:127–134. Sawaya R, Highsmith RF. Postoperative venous thromboembolism and brain tumors: Part iii. Biochemical profile. J Neurooncol. 1992;14:113–118.

Neurosurgery

15–40%

Stroke

20–50%

Spinal cord injury

60–80%

Critically ill

10–80%

History and Examination

History

Physical Examination

Venous Thromboembolism

Nosocomial Infection

Gastric Ulcer/Anemia

Neurologic Examination

Prophylaxis and Preventive Strategies

Venous Thromboembolism

General Principles

Disease Category

Recommendation

Level of Recommendation

General

Mechanical methods alone have not been shown to reduce PE or death in any group.

Use mechanical methods alone in patients at high risk of bleeding, or as an adjunct to anticoagulant based prophylaxis.

Aspirin is not recommended as prophylaxis for any group.

Routine screening Doppler in asymptomatic patients is not cost effective and not recommended.

Grade 1A (ACCP)

Grade 2A (ACCP)

Grade 1A (ACCP)

Grade 1A (ACCP)

Craniotomy

Compression boots for all patients

Heparin SQ or LMWH are options.

A randomized controlled trial of enoxaparin plus compression stockings started 24 h postop compared with compression stockings alone in elective neurosurgery patients showed significantly fewer DVT/PE in the enoxaparin group, with no significant increase in bleeding.

Heparin SQ or LMWH plus compression boots are recommended for high-risk patients.

Grade 1A (ACCP)

Grade 2B, 2A (ACCP)

Grade 2B (ACCP)

Elective spine surgery

Early mobilization and no prophylaxis if no risk factors

Use some form of prophylaxis in older patients, history of cancer, previous VTE, neurologic deficit, or anterior approach. Options:

Heparin SQ

LMWH SQ

Compression boots alone

GCS alone

If multiple risk factors: SQ heparin or LWMH plus GCS and/or compression boots

Grade 2C (ACCP)

Grade 1B (ACCP)

Grade 1C (ACCP)

Grade 1B (ACCP)

Grade 1B (ACCP)

Grade 2B (ACCP)

Grade 2C (ACCP)

Acute spinal cord injury (SCI)

LMWH commenced as soon as hemostasis present

Alternatives: compression boots + unfractionated heparin or LMWH

If anticoagulant thromboprophylaxis is contraindicated because of high bleeding risk, compression boots or GCS is recommended.

When bleeding risk decreases, pharmacologic prophylaxis should be substituted or added.

For patients with an incomplete SCI associated with spinal hematoma on CT or MRI, use mechanical thromboprophylaxis at least for the first few days after injury.

Recommend against unfractionated heparin alone

A randomized controlled trial in SCI patients of heparin t.i.d. + compression boots vs LMWH found VTE in 16% of heparin group and 12% in LMWH group, major bleeding in 5% of heparin group, and 3% of LMWH group.

Recommend against IVC filter as primary prophylaxis IVC filters do NOT prevent DVTs. Complications of IVC filter placement include erosion/perforation of IVC wall, filter migration, improper initial placement, distal thrombi formation, arterial-venous fistula at insertion site, infection, IVC occlusion, and 0.12% incidence of death.

Grade 1B (ACCP)

Grade 1B (ACCP)

Grade 1C (ACCP)

Grade 1A (ACCP)

Grade 1C (ACCP)

Grade 1C (ACCP)

Grade 1A (ACCP)

Grade 1C (ACCP)

Intracerebral hemorrhage

All patients should have compression stockings.

After documentation of cessation of bleeding, SQ heparin or LMWH may be started in patients with hemiplegia after 3–4 days.

In a randomized trial, 68 patients with ICH were treated with SQ heparin at days 2, 4, and 10 postbleed. Rates of PE were 0, 4, and 13% at each time epoch with no increase in bleeding in the early time group.

Class I, level B (AHA/ASA)

Class IIb, level B (AHA/ASA)

Traumatic brain injury

Compression boots recommended in patients who do not have lower extremity injury

SQ heparin or LMWH + mechanical prophylaxis may be used.

Level III (Brain Trauma Foundation)

Level III (Brain Trauma Foundation)

Ischemic stroke

Early mobilization is recommended.

SQ administration of anticoagulants to prevent DVT in immobilized patients is recommended. The timing for starting these medications is not known.

In a randomized trial of 1,335 ischemic stroke patients to enoxaparin vs. SQ heparin b.i.d., those who received enoxaparin had significantly fewer VTE, DVT, and PE without any significant increase in intracranial or clinically significant bleeding.

Aspirin is a potential intervention to prevent DVT, but it is not as effective as SQ anticoagulants.

Compression stockings are recommended for patients who cannot receive SQ anticoagulants.

Class I, level C (AHA/ASA)

Class I, level A (AHA/ASA)

Class IIa, level A (AHA/ASA)

Class IIa, level B (AHA/ASA)

Brain tumor

All cancer patients are high risk for VTE

SQ heparin or LMWH + compression boots

No evidence for IVC filter

Prophylactic IVC filter carries high complication rates in cancer patients and risks often outweigh benefits

Incidence of VTE: meningioma (72%), GBM (60%), metastasis (20%)

No society guidelines

| Infection Type | Preventive Strategy |

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia | Aggressive weaning Daily sedation vacation Early tracheostomy Consider noninvasive ventilation Oral ETT (rather than nasal intubation) ETT cuff pressure >20 cm H2O Semirecumbent position 30–45 degrees unless contraindicated Oral hygiene (every 4 h and prn) Enteral feedings rather than total parenteral nutrition Pneumococcal vaccine for patients >65 years |

| Catheter-related bloodstream infection | Maximal sterile barrier Preferential use of subclavian line site (greater infection risk: femoral > internal jugular > subclavian) 2% chlorhexidine skin preparation Use of preassembled insertion kits Use catheters with least number of ports needed Replace transparent dressings when loose, damp, or otherwise every 7 days Replace gauze when loose, damp, or otherwise every 2 days No routine line replacement No guide wire exchanges Selective use of antimicrobial/antiseptic impregnated catheters Remove lines when no longer needed Glycemic control |

| Surgical site infection (SSI) | Most SSIs occur between days 5–10 postop. Smoking cessation Shower preop with antimicrobial soap. Patient should not shave operative field. Intraop skin prep with chlorhexidine Surgeon hand and forearm surgical scrub X 5 minutes preop Use closed suction drains and insert through a separate incision. Keep operative incision covered for 48 h postop, then keep primarily closed incision open after 48 h. Change dressing with sterile technique. Maintain normoglycemia. Minimize periop transfusions. Perioperative antibiotics. First dose to start within 60 minutes before incision. A single preoperative dose is the recommended standard, but antibiotics can be continued for a maximum of 24 h, except in cardiothoracic surgery (48–72 hours) and in solid organ transplant (48 h). For craniotomy, spine surgery, transsphenoidal surgery, and CSF shunting procedures, use: Cefuroxime 1.5 g IV q 6 h or cefazolin 1 g IV q 4 h intraoperatively (to be D/C’d after 24 hours) For neurosurgery with entry into the sinuses: Cefuroxime 1.5 g IV q 6 h and ampicillin 1 g IV q 6 h For immediate-type penicillin (PCN) allergy: Vancomycin 1000 mg IV q 12 h and gentamicin 1.5 mg/kg (ideal body weight) q 8 h (to be D/C’d after 24 h) For trauma: first- or third-generation cephalosporin, given for no longer than 24 h, even in colon injuries, as long as trauma is >4h old. Routine vancomycin and third-generation cephalosporin prophylaxis should not be given. |

| Clostridium difficile diarrhea | Judicious use of antibiotics Place infected patients on contact precautions. Meticulous hand washing with antiseptic soap and water before and after each contact Alcohol/Purell does not kill C. difficile spores. Dedicated single-use patient care items for those infected Terminally clean (with bleach) rooms of those infected. Treat clinically infected (not carriers) patients who have active diarrhea with PO or IV metronidazole or PO vancomycin (if refractory to metronidazole). |

| Meningitis/ventriculitis | A randomized trial did not show any benefit to routine EVD change (risk of infection rises over the first 4 d, but then plateaus). A retrospective study of 308 patients showed the same meningitis/ventriculitis rate (4%) for those who received only periprocedural antibiotics compared with those who had antibiotics for the duration the drain was in place. Using only periplacement antibiotics would save $80,000 a year. A prospective study of 228 patients showed that those who got periprocedure Unasyn had an 11% CSF infection rate and a 42% extracranial infection rate, compared with those who had Unasyn and aztreonam for the duration of catheter placement (3% CSF infection, 20% extracranial infection). Those who received antibiotics for the duration grew more MRSA and Candida. Both chemical and infectious meningitis can produce CSF leukocytosis and low glucose. Using prophylactic antibiotics for the duration of drain placement makes cultures unreliable and selects for resistance. Tunneling and surveillance protocols can limit infection. Minimize shunt manipulation and tapping. Use sterile technique with shunt tapping. Antibiotic-coated catheters are associated with fewer positive CSF cultures. |

| Indwelling catheter-related infection | Prophylactic antibiotics have not been shown to be useful for central lines, Foley catheters, lumbar drains, JP drains, or a Hemovac, and can breed resistance. We do not recommend prophylactic antibiotics for drains of any kind. |

Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; D/C, discontinue; ETT, endotracheal tube; EVD, external ventricular drain; IV, intravenously; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; prn, as needed; PO, by mouth; q, every.

Data from: Hemovac autotransfusion system; Zimmer Orthopaedic Surgical Products, Dover, OH. Gojo, Akron, OH. Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, New York, NY. Niederman MS. The clinical diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Respir Care 2005;50(6):788–796, discussion 807–812.

Szalados, JE, ed. Adult Multiprofessional Critical Care Review. Mount Prospect, IL: Society of Critical Care Medicine; 2007.

O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Dellinger EP, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep 2002;51(RR-10):1–29.

Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, et al. An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med 2006;355(26): 2725–2732.

Bratzler DW, Houck PM. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for surgery: an advisory statement from the National Surgical Infection Prevention Project. Am J Surg 2005;189(4):395–404.

Surgical Care Improvement Project. Available at: www.medqic.org. Accessed August 10, 2008.

Wong GK, Poon WS, Wai S, Yu LM, Lyon D, Lam JM. Failure of regular external ventricular drain exchange to reduce cerebrospinal fluid infection: result of a randomised controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002;73(6):759–761.

Alleyne CH Jr, Hassan M, Zabramski JM. The efficacy and cost of prophylactic and perioprocedural antibiotics in patients with external ventricular drains. Neurosurgery 2000;47(5):1124–1127, discussion 1127–1129.

Poon WS, Ng S, Wai S. CSF antibiotic prophylaxis for neurosurgical patients with ventriculostomy: a randomised study. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 1998;71:146–148.

Zabramski JM, Whiting D, Darouiche RO, et al. Efficacy of antimicrobial-impregnated external ventricular drain catheters: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. J Neurosurg 2003;98(4):725–730.

| Product | Transfusion/Administration Indication |

| Packed red blood cells | Transfuse for active bleeding Transfuse for a hematocrit <30% for acute ischemia (MI, consider for acute cerebral ischemia, SAH with vasospasm). For all other critically ill patients, restrict transfusion for those with Hgb <7 g/dL. TRICC trial randomized 838 critically ill patients to restricted transfusion for a Hgb <7.0 g/dL vs. liberal transfusion for a Hgb <10 g/dL, 26% of patients had a history of CAD, and 5% had a neurologic diagnosis. Overall, there was no difference in survival between the restrictive and liberal transfusion groups. Subgroups with APACHE score <20 or age <55 years had significantly better survival with restricted transfusion. The restrictive group had significantly fewer cardiac complications, MI, pulmonary edema, and multisystem organ dysfunction. In a retrospective study of 78,974 patients >65 years old with acute MI, transfusion for a hematocrit <30% was associated with a lower 30-day mortality. |

| Erythropoietin | Restrict use of erythropoietin to those with anemia receiving renal replacement therapy (target Hgb 7–9 mg/dL). In a randomized controlled trial of 1460 critically ill medical, surgical, and trauma patients, weekly erythropoietin did not decrease the number of patients who required an RBC transfusion or the number of units transfused (Hgb target 7–9 g/dL). Treatment with erythropoietin was associated with a significantly higher risk of thrombotic events. |

| Fresh frozen plasma | Transfuse for patients with vitamin K deficiency or warfarin therapy and active bleeding (if significantly increased PT, INR, or PTT). Transfuse for patients with vitamin K deficiency or warfarin therapy who require surgery or an invasive procedure (if significantly increased PT, INR, or PTT). Transfuse for patients with liver disease and active bleeding (if significantly increased PT, INR, or PTT). Transfuse for patients with liver disease before surgical or invasive procedures (except percutaneous liver biopsy, paracentesis, or thoracentesis) (if significantly increased PT, INR, or PTT). Transfuse for acute DIC with treatable triggering condition and active bleeding (if significantly increased PT, INR, or PTT). Transfuse for TTP/HUS and initial plasmapheresis. Transfuse acquired deficiencies of a single coagulation factor when DDAVP or appropriate factor concentrates are ineffective/unavailable and there is serious bleeding or before emergency surgical or invasive procedure. Give FFP along with massive transfusion of RBCs (>1 blood volume and significantly increased or unknown PT, INR, or PTT). |

| Platelets | Risk of severe bleeding rises when platelets <5–10,000/UL. Risk of spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage when platelets <1000/UL (0.76% per day) Platelets are not indicated for stable thrombocytopenic patients with counts >10,000/UL Consider maintaining platelets >50,000/UL in patients with recent intracranial or spinal hemorrhage. Consider maintaining platelets >50,000/UL in patients who require invasive procedures. Transfuse platelets for patients with defective platelets (due to antiplatelet medication, EtOH, renal failure, etc.), who are actively bleeding, had a recent intracranial or spinal hemorrhage, or are having an invasive procedure. Platelet transfusion (in addition to cryoprecipitate) is recommended for patients with bleeding after tPA. Platelet transfusion can worsen TTP and HIT. |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; DDAVP, 1,desamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; EtOH, ethyl alcohol; ETT, endotracheal tube; FFP, fresh frozen plasma; Hgb, hemoglobin; HIT, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia; HUS, hemolytic uremic syndrome; INR, international normalized ratio; MI, myocardial ischemia; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; RBC, red blood cell; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; tPA, tissue plasminogen activator; TTP, thrombotic thrombocytoperic purpura; UL, microliter.

Data from: Hebert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med 1999;340(6):409–417.

Wu WC, Rathore SS, Wang Y, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Blood transfusion in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2001;345(17): 1230–1236.

Corwin HL, Gettinger A, Fabian TC, et al; EPO Critical Care Trials Group. Efficacy and safety of epoetin alfa in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 2007;357(10): 965–976.

Lauzier F, Cook D, Griffith L, Upton J, Crowther M. Fresh frozen plasma transfusion in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2007;35(7):1655–1659.

Gastric Ulcers

Prophylaxis is recommended in patients with the following conditions:12

- Coagulopathy

- Mechanical ventilation >48 hours

- Patients with at least two of the following: sepsis, intensive care unit (ICU) stay >1 week, occult bleeding >6 days or more, and use of high-dose corticosteroids (>250 mg/day of hydrocortisone or equivalent).

- Glasgow Coma Scale ≤10

- Thermal injuries to >35% body surface area

- Partial hepatectomy and/or hepatic failure

- Multiple trauma and spinal cord injuries

- Organ transplant patients

Enteral feeding is an effective, nonpharmacologic method for gastrointestinal (GI) prophylaxis. Histamin-2 receptor antagonist (H2A), sucralfate, proton-pump inhibitors (PPI), antacids, and prostaglandin analogues decrease the incidence of upper GI bleeding in ICU patients. H2A blockers should be used with caution in the neuro-ICU, as they may cause significant encephalopathy and interact with anticonvulsants. Concerns for higher incidence of nosocomial pneumonia associated with H2A use remain controversial. Both H2 blockers and PPIs can aggravate Clostridium difficile colitis, and carafate or sulcrafate should be used preferentially in this context.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree