OBJECTIVES

Highlight the clinical consequences of language barriers.

Describe evidence for professional interpreters and for bilingual clinicians.

Describe the limited-English–speaking population in the United States.

Review policies pertaining to linguistic access in health care in the United States.

Describe institutional responses to overcome language barriers.

Summarize strategies to address language barriers in clinical practice.

INTRODUCTION

Health-care providers are better educated and more scientific than ever before, but they have a great failing: providers sometimes do not communicate effectively with their patients or with the patient’s family.1

The current health-care system offers some of the most technologically advanced medicine in the world. At the same time, millions of people in the United States, and increasingly throughout the world, have limited access to the most basic feature of good medical care: adequate communication.2 Effective patient–provider communication is essential to providing good medical care. Taking an accurate history is fundamental to being a diagnostician; the history is the key to the final diagnosis in 56–82% of cases.3 Moreover, the quality of communication also affects patient and physician satisfaction, patient adherence, and clinical outcomes.4 Unfortunately, in the United States, many people are unable to reap the benefits of effective communication because they cannot speak English well.

The ability to navigate a health-care system depends in large part on the capacity to speak and understand the official language. Language barriers can hinder care from simple communications such as calling for an appointment, to emergent situations such as explaining symptoms to an ambulance paramedic, to more nuanced exchanges such as discussing treatment risks and benefits with a doctor. The consequences can be dire.

This chapter is designed to help readers understand the impact of language barriers on both patients and clinicians, and provide guidance to overcome them. Although many of the ideas in this chapter pertain to language barriers in any health-care setting, we will focus on language barriers in the United States. We begin with an overview of language barriers in health care, including who faces these barriers, how language barriers affect health care, and current policies regarding linguistic access in US health-care settings. We conclude with practical suggestions clinicians may draw from to better care for limited-English–speaking patients.

LIMITED ENGLISH PROFICIENCY AND HEALTH CARE

Miguel Hernandez immigrated to the United States 5 years ago. Despite working long days, he takes English as a second language (ESL) classes in the evenings and on weekends. He is able to say and understand basic things in English, but this becomes more difficult when he is under stress. When he presents to the emergency department with an episode of recurrent nephrolithiasis, he does not know enough English to share his past medical history, alert the nurse of his codeine allergy, or describe his symptoms in detail to his doctor.

Limited English proficiency (LEP) refers to patients such as Mr. Hernandez who cannot speak, read, write, or understand the English language at a level that permits them to interact effectively with health-care providers. Since 1980, the US census has used a set of standardized questions to ask about language ability. Anyone who reports speaking English less than “very well” (i.e., “well,” “not well,” or “not at all”) is considered to be LEP by this population criterion.5

In clinical settings, a two-step process most reliably ascertains LEP status6:

Step 1: Ask the patient to report their proficiency in English. For those who report that they speak English less than “very well.”

Step 2: Ask the patient to report their preferred language for health care.

Guidelines, including from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) (2009), emphasize this two-step approach to the collection of language data rather than asking patients simply if they need an interpreter—a question that can be misunderstood, especially if an English-speaking family member accompanies the patient. If patients are asked only about their language preference, about 20% may be misclassified as LEP as they prefer their native language for health care yet speak English “very well.”7 This misclassification may obscure LEP-associated health-care disparities and confuse quality improvement efforts.

In the case of Miguel Hernandez, basic command of English that may suffice at the grocery store or post office may be inadequate to communicate in health-care settings. Given that communication is bidirectional, another important gauge of a patient’s LEP status is whether or not the clinician believes the patient is capable of expressing concerns and understanding recommendations.

THE LIMITED-ENGLISH–SPEAKING POPULATION IN THE UNITED STATES: LARGE, DIVERSE, AND GROWING

According to the US census, the number of Americans aged 5 years or older who spoke a language other than English at home grew from 23.1 million in 1980 to 60.5 million in 2011. The percentage who were considered LEP experienced similar growth,5 increasing from 4.8% in 1980 to 8.7% in 2011.

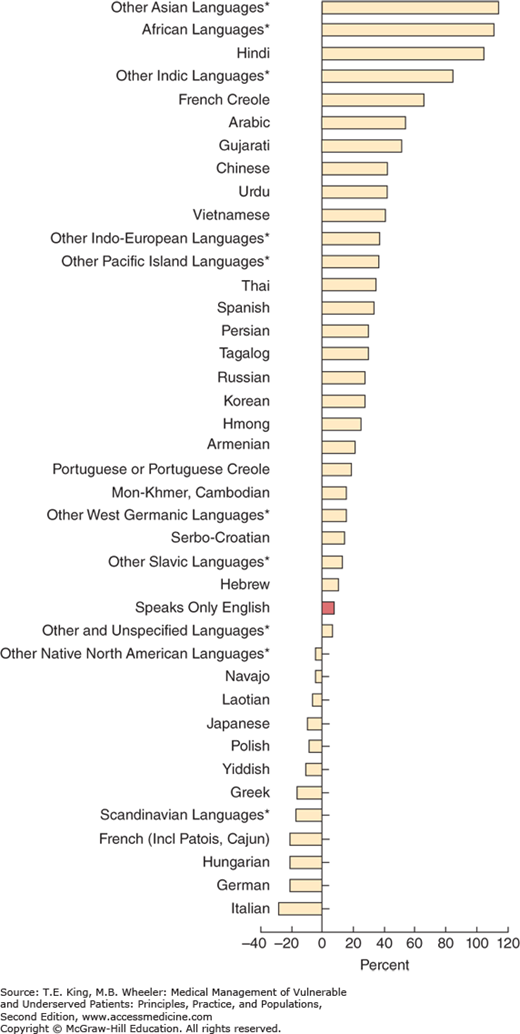

More than 380 different languages are spoken across the United States.5 Although Spanish accounts for about 62% of people who speak a language other than English at home, because of changes in immigration patterns, other languages are increasingly likely to be encountered (Figure 31-1). Between 1980 and 2010, Vietnamese speakers experienced the largest percent growth at 559%. During the same time period, four languages that had less than 200,000 speakers in 1980 more than doubled. These languages were Vietnamese, Russian, Persian, and Armenian.5

Figure 31-1.

Percentage change in language spoken at home: 2000–2011. The figure depicts the changes in language spoken at home for individuals 5 years of age or older over a 10-year span. (Adapted from Ryan C. Language Use in the United States 2011 American Community Survey Reports. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau, 2013. Available at https://www.census.gov/prod/2013pubs/acs-22.pdf. Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Census 2000 and 2011 American Community Survey.)

Among these various language groups, the proportion of people who are LEP varies considerably. For example, more than 50% of Korean, Chinese, and Vietnamese speakers and 46% of Spanish speakers are LEP, whereas 20% or less of French or German speakers are LEP.5 The greatest concentrations of LEP residents are in California, where according to the 2010 US Census Bureau American Community Survey, nearly one in every five people is considered LEP.8 Other states with high percentages of LEP residents include Texas (14.4%), New York (13.5%), New Jersey (12.5%), Nevada (12.3%), Florida (11.9%), Hawaii (11.8%), and Arizona (9.9%).8 However, the greatest increase in LEP populations has been in southeastern and western states such as Georgia, North Carolina, and Nevada, all of which experienced more than 300% growth8 between 1990 and 2010. Given the relative lack of established language access services in these “emerging” LEP communities, clinicians working in these high-growth states may face particular challenges in caring for their LEP patients.

LEP individuals are more likely than English-speaking members of the same ethnic group to be older, less educated, low income, and to have been in the United States for a shorter period of time.9 Given these demographic patterns, clinicians caring for LEP patients often encounter concurrent challenges of poverty, lack of insurance, and low functional health literacy and cross-cultural communication. However, although these issues are often intermeshed, they are also distinct, and require sensitivity to the individual patient’s background. For example, a patient may speak little English, but be highly educated, literate in her or his native language, and accustomed to and accepting of western biomedical concepts.

LANGUAGE BARRIERS HAVE CLINICAL CONSEQUENCES

Ha Lang, an elderly Cantonese-speaking woman, is hospitalized because she took too much warfarin. Late at night, she gets up to go to the bathroom. A nurse on duty stops her and tries to get her back into bed. When Mrs. Lang persists in wanting to go to the bathroom, the nurse thinks she is agitated. Instead of calling for an interpreter, the nurse has Mrs. Lang put in arm restraints and gives her a sedative (Box 31-1).

In studies with a wide range of LEP health consumers, language barriers are often reported as being one of the most important, if not the most important, barrier to accessing care.10,11,12 When compared with English speakers, limited-English–speaking patients are less likely to be insured13,14 or know about public health insurance programs,15 and their children are less likely to have a usual source of care.16 Limited-English–speaking patients are also less likely to receive physician visits,17,18 dental care,19 eye examinations,19 mental health visits,17 or referrals from the emergency department after discharge.20

Even when limited-English–speaking patients are able to access care, they have been found to be less likely to understand what transpires in the clinical encounter, from basic medical terminology21 to discharge diagnoses,22 to prescribed medications.23,24 In a telling study that sought to evaluate two types of state-of-the-art medical interpretation, patients presenting to a New York City emergency department were nearly twice as likely to report comprehension of diagnosis if their physician spoke their language than if the encounter was conducted via either of the excellent interpreting systems.25

Patients with language barriers are less likely than patients who do not have language barriers to engage in active exchanges with their providers26 or feel as if they played an active part in decision making.27 Perhaps as a result, they are less likely to be satisfied with their medical encounters,27,28,29,30 their individual providers,31,32 and the institutions that provide care.23,29

In nearly every clinical setting that has been examined, language barriers appear to result in lower-quality care. Limited-English–speaking patients are less likely to receive recommended preventive care such as mammograms,17 pap smears,33,34 colon cancer screenings,35 and influenza vaccinations.17,35 In psychiatric settings, LEP status has been associated with inadequate evaluation and diagnosis.36,37 In palliative care settings, LEP patients are less likely to have adequate symptom control,38 and in obstetrical settings, they are at higher risk of experiencing a nonsterile delivery.39 Once LEP patients present to the emergency department, they receive more diagnostic tests,40 are more likely to be hospitalized,14,41 and, once hospitalized, tend to have a longer length of stay42 than English-speaking patients with similar conditions. Patients with language barriers are less likely to receive informed consent for invasive procedures, despite the clear violation of law.43

Box 31-1. Common Pitfalls in Health Care for Limited-English–Speaking Patients

Language is one of the most significant barriers to health care for immigrants in the United States.

Limited-English–speaking patients understand less of what occurs during health-care visits than English speakers.

Limited-English–speaking patients tend to receive lower quality of care than those who speak English very well.

Using interpreters has been shown to improve understanding and quality of health care, though a comprehension gap remains when compared with care provided by bilingual clinicians.

Despite growing numbers of limited-English–speaking patients and legal mandates requiring provision of interpreter services, these services are often lacking or inadequate.

PATIENTS HAVE A LEGAL RIGHT TO LANGUAGE ACCESS IN HEALTH CARE

There are a number of federal and state laws that give limited-English–speaking patients a legal right to language assistance services in health-care settings. On the federal level, Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act has been interpreted by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to mean that any health-care organization that receives federal money—for example, Medicare or Medicaid payments—is obligated to ensure linguistic access for its LEP patients.44 More recently, HHS’ Office for Civil Rights has issued guidelines for health-care providers to follow in determining what type and extent of language assistance services to offer.45 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) also has issued regulations that require Medicaid health plans to make interpreter services available to their enrollees free of charge.46 The Affordable Care Act (ACA) explicitly requires insurers and health-care institutions to provide written translation and interpreting services for LEP patients of qualifying language groups.47 (For a quick primer on the ACA and language access services, see http://www.languagescientific.com/language-services-blog/affordable-care-act-language-service-requirements.html.)

Despite legal mandates, limited-English–speaking patients continue to face barriers when they attempt to access health services. This results, in part, from incomplete coverage and inconsistent enforcement of federal and state laws, limited availability of trained health-care interpreters; lack of adequate financing for language access services; and clinician and patient willingness to just “get by.”48 In the face of these challenges, it is critical that health-care providers understand how they can optimize their communication with LEP patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree