Disturbance of consciousness with impaired attention

Change in cognition or disturbance of perception

Not better accounted for by a preexisting, established, or evolving dementia

Memory impairment (most commonly in recent memory)

Disorientation to time and place and rarely to self

Speech and language disturbances (dysarthria, dysnomia, dysgraphia, aphasia)

Perceptual disturbances, including misinter-pretations, illusions, and hallucinations (most commonly visual)

Acute onset (hours to days) and fluctuating during course of the day

Always attributable to a medical or organic cause: look for evidence in the history, physical examination, or laboratory data to indicate that it is direct physiologic consequence of general medical condition, substance intoxication or withdrawal, use of medication, or toxin exposure

Prevalence at medical admission: 10%-31%

Older postoperative patients: 15%-53%

Patients in ICUs: 70%-87%

Associated with serious adverse outcomes, including increased mortality at discharge and 12 months, length of stay, hospital costs, and institutionalization

Increased or decreased psychomotor activity (hyperactive vs. hypoactive delirium)

Disorganization of thought process (ranging from mild tangentiality to incoherence)

Emotional disturbances, including fear, anxiety, depression, irritability, anger, euphoria, and apathy

Disturbed sleep-wake cycle, at times completely reversed with exacerbation of symptoms at bedtime (also known as sundowning)

Impaired judgment

Advanced age

Dementia (see page 58 for more information)

Depression (see page 65 for more information)

Brain injury

History of alcohol abuse (see page 102 for more information)

History of delirium

Functional status (immobility, history of falls, low level of activity)

Sensory impairment (visual and hearing)

Malnutrition, dehydration

Postoperative state, intensive care unit (ICU) stay

Prolonged sleep deprivation

Altered mental status

Change in mental status

Confusion

Disorientation

Dementia

Memory problems

Depression

Agitation

Psychosis

Withdrawal (from alcohol or benzodiazepines)

Wernicke’s (triad: confusion, ataxia, ophthalmoplegia)

Hypoglycemia

Hypoxia (myocardial infarction [MI], congestive heart failure, anemia, carbon monoxide toxicity)

Hypoperfusion of the central nervous system (CNS)

Hypothermia

Hypertensive encephalopathy

Intracerebral hemorrhage

Infection

Meningitis or encephalitis

Metabolic (renal failure, hepatic failure, diabetic ketoacidosis, electrolyte disturbances, acid-base disturbances, adrenal insufficiency)

Poisons (heavy metals, anticholinergics, overdose, intoxication, drug-drug interactions)

Seizures or status epilepticus

Delirium is a reversible condition and should be considered a medical emergency

Treat the underlying medical or organic cause(s)

Address and minimize contributing factors

Acute interventions (see Agitation page 13 for more details)

Provide orienting environmental cues (clock, calendar, names of care providers posted where patient can see them clearly)

Provide adequate social interaction

Have the patient use eyeglasses and hearing aids appropriately

Mobilize the patient as soon as possible

Ensure adequate intake of nutrition and fluids

Educate and support the patient and his or her caregivers

TABLE 2-1 Selected Causes of Delirium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 2-2 Approach to the Evaluation of Delirium | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

If possible, avoid using medications until the underlying cause has been determined

Use lower doses for elderly patients and persons with parkinsonism, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and mental retardation

First-line medications are typical or atypical antipsychotics (see Agitation page 13 for more details)

Begin with a single antipsychotic and titrate the dose to symptom response

Bedtime or twice-daily (BID) dosing on an as-needed (PRN) basis is often helpful

Avoid benzodiazepines and anticholinergics

They may increase confusion or paradoxically increase disinhibition

Watch for respiratory depression and oversedation

Benzodiazepines are associated with prolongation and worsening of delirium symptoms

Consider nonbenzodiazepine anxiolytics (see Agitation page 13 for more details)

Used when less restrictive measures have failed or when the patient exhibits severe agitation or violent behavior (see Agitation page 13 for more details)

Agitation: a state of poorly organized and aimless psychomotor activity that stems from physical or emotional unease

Signs and symptoms: motor restlessness, hyperactivity, irritability, decreased attention, increased distractibility, increased reactivity, increased mood lability, uncooperative or inappropriate behaviors, decreased sleep

Psychological correlates: fear, anger, anxiety, pain or discomfort

Agitation is a symptom that may occur in a variety of psychiatric disorders

Compare with aggression: overt behavior involving an intent to inflict noxious stimulation on or to behave destructively toward another organism

May be impulsive or premeditated

Most often not primarily caused by a psychiatric etiology

>21% of annual psychiatric ED visits (˜900,000) involve agitated pts with schizophrenia (Marco & Vaughan, 2005)

1.7 million psych ED visits annually involve agitated patients with all diagnoses (Allen & Currier, 2004)

Seen in 50% of community-dwelling patients with Alzheimer’s disease

Seen in 90% of nursing home residents with dementia (Teri et al., 1989)

Delirium

Psychosis

Mania

Anxiety or depression

Dementia

Intoxication or withdrawal

Medication side effects

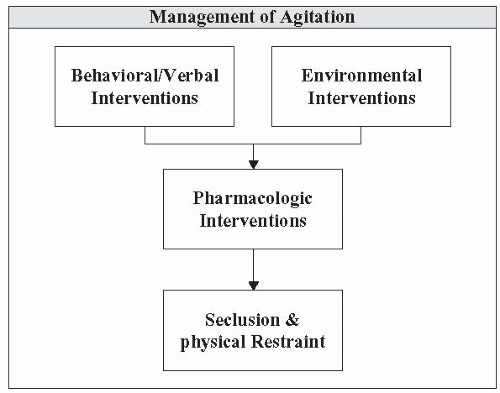

Agitation is a behavioral emergency

Maintain patient and staff safety

Maximize patient comfort

Screen for and treat medical abnormalities

Treat drug intoxication and withdrawal

Treat psychiatric symptoms (e.g., anxiety, psychosis)

Use tranquilizing medications if needed

Use good eye contact (avoid staring; watch facial expressions)

Watch the person’s interpersonal space (distance, altitude, movement)

Use good posture (relaxed, open handed, equal egress, 90 degree)

Don’t touch!

Be empathic to the patient’s condition and problems

Accept what the patient says (don’t challenge)

Anticipate shame, vulnerability, and loss of self-esteem

Express concern and desire to protect the patient from harm

Acknowledge the patient’s power to make decisions but be firm about boundaries and limits

Use distractions (food, drink, blanket, magazine, phone call)

Report to patient what you observe (“you are scaring me”)

Remove all potentially dangerous objects

Isolate (decrease interpersonal stimulation)

Decrease external stimuli (quiet room, individual examination room)

Use a show of force (security)

Provide one to one observation

These are required when patients are at substantial risk of harming themselves or others and when less restrictive measures have failed

Always use the least restrictive means possible. Try alternative measures first. Behavioral or verbal and environmental interventions as above; as needed medications and pharmacologic management

Implement for the least amount of time possible, as mandated by the clinical situation

Know your specific state-mandated protocol for initial assessment and reevaluation of restrained patients

Consider criteria for release (e.g., “able to engage in mutual dialogue with staff, noncombative”). Sleeping should be a criterion for release EXCEPT when it is thought that releasing the patient would lead to further agitation

Morbidity associated with physical restraints: fractures, abrasions, bruises, aspiration pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism, decubitus ulcers (from prolonged immobilization)

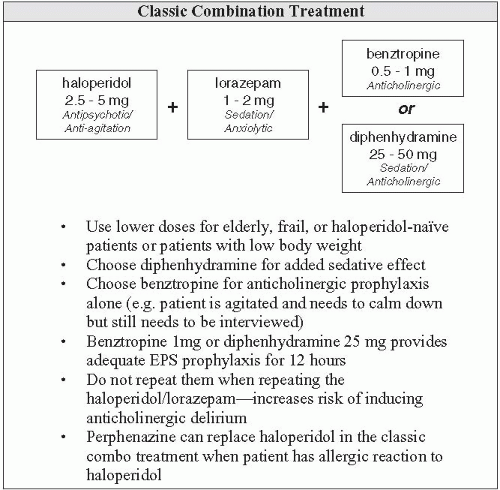

Offer the patient as needed medications

Try to use any sedating or antipsychotic medications the patient is currently taking

The mainstay of treatment is use of typical and atypical antipsychotics; combine them with sedating medications or anticholinergic medications if indicated

If the patient is unwilling to take medications by mouth or if a faster onset is required, use the intramuscular (IM) route (or the intravenous [IV] route if available)

Titrate dose to symptom response

Routes of administration (how long to take effect)

Orally (PO): takes effect in 20-30 min; maximum effect in 1 hr

IM: takes effect in 10-15 min; maximum effect in 30 min

IV: takes effect in few minutes

Special populations: elderly patients, children, medically compromised patients

Start low, go slow

Avoid anticholinergic agents (risk of delirium)

Give low-dose benzodiazepines only (may paradoxically increase disinhibition)

Consider atypical antipsychotics (especially risperidone and olanzapine) in geriatric patients with dementia and agitation

TABLE 2-3 Typical Antipsychotics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In general, there is a lower risk of extrapyramidal side effects (EPS) than with typical antipsychotics, but EPS may still occur

When using IM olanzapine, avoid coadministration with other medications, especially benzodiazepines or other CNS depressants as there have been eight case reports of sudden death, cardiovascular complications, and respiratory depression

Anticholinergics: use with high-potency neuroleptics (haloperidol) to prevent EPS

This is especially important in young males and patients with previous dystonic reactions

Watchfordeliriumwhenusing inelderly,mentally retarded,or TBIpatients

Benzodiazepines: use for anxiety symptoms, withdrawal, sedation, akathisia

Watch for delirium and paradoxically increased disinhibition when using in elderly, mentally retarded, or traumatic brain injury patients

Nonbenzodiazepine anxiolytics: use for anxiety symptoms in patients in whom benzodiazepines are risky

TABLE 2-4 Atypical Antipsychotics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

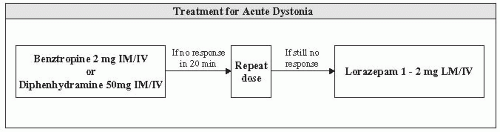

Higher frequency of EPS with typical antipsychotics

Includes acute dystonia, akathisia, parkinsonian-like effects

Acute muscular rigidity and cramping

Most likely occurs within the first week of neuroleptic initiation

Particularly common after IM haloperidol

Risk factors: young men, history of dystonic reaction

Very uncomfortable and frightening for patients

Watch for laryngeal dystonia, which includes airway compromise and is a medical emergency

Treat with benztropine, diphenhydramine, or lorazepam

If an antipsychotic is being continued, maintain the anticholinergic for 2 weeks (benztropine 2 mg BID for 14 days)

TABLE 2-5 Adjunctive Medications | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Feeling of inner restlessness and the need to move, especially the legs

Difficult to distinguish from anxiety and agitation related to psychosis; increased restlessness after initiation of a typical antipsychotic should always raise suspicion for akathisia

Treatment varies by clinical situation

Symptoms include bradykinesia, rigidity of the limbs, resting tremors, cogwheeling, masked facies, stooped posture, festinating gait, and drooling

Onset of symptoms is usually after several weeks of therapy

Most common in elderly patients who are taking high-potency drugs

Treatment:

Switch from a typical to an atypical antipsychotic

Decrease to the lowest effective dose of antipsychotic

Add a fixed dose of antiparkinson drug (benztropine 1-2 mg BID)

TABLE 2-6 Treatment for Akathisia | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

All antipsychotics have quinidine-like cardiac effects, which increase the risk of cardiac arrhythmias through prolongation of corrected QT interval (QTc)

Obtain a baseline electrocardiogram(ECG) or follow-up ECGin patients with:

Known elevated QTc

Family history of sudden death

Known heart disease

Known to be taking drugs that prolong QTc interval (e.g., quinolones)

Provide cardiac monitoring at higher doses (watch for QTc prolongation and torsades de pointes)

Replete K and Mg to a high normal range

Dry mouth

Hyperthermia

Constipation

Urinary retention

Blurred vision

Narrow-angle glaucoma

Memory deficits

Hallucinations

Delirium(see page 9 for more information)

Eye pain and redness

Blurred vision, decreased visual acuity

Extreme light sensitivity

Nausea and vomiting

Seeing halos around lights

Oversedation and respiratory compromise: carefully monitor vital signs

Orthostasis and fall risk; monitor orthostatic blood pressure (BP) and place the patient on fall precautions when appropriate

Motoric immobility: with rigidity, including waxy flexibility (e.g., resistance to arm repositioning), catalepsy or with minimal response to stimuli (stupor)

Excessive motor activity: apparently purposeless and not influenced by stimuli (e.g., constant unrest, screaming, taking off clothes, running down hallway)

Extreme mutism: verbal unresponsiveness (e.g., while occasional eye contact) or extreme negativism: motiveless resistance to all instructions or maintenance of a rigid posture against attempts to be moved (e.g., grinding teeth while the jaw is pulled down, squeezing the eyelids during an eye examination)

Peculiarities of voluntary movement:

Inappropriate or bizarre posture (e.g., sitting or standing without reaction)

Stereotyped movement (e.g., repetitive patting or rubbing oneself)

Prominent mannerism (e.g., walking on tiptoe)

Grimace (e.g., forceful, odd smile)

Echolalia or echopraxia: repeating the words or movements of the inter-viewer

Neurologic or medical illness (e.g., toxic-metabolic, infections, CNS diseases, drugs, poisoning)

Psychiatric disorder (e.g., mood disorders, schizophrenia, acute psychosis, conversion disorder)

Early recognition

Diagnosis and treatment of neuromedical illnesses: obtain a complete blood count (CBC), complete metabolic panel, creatine kinase (often increased), Fe (decreased Fe is a risk factor for catatonia), urinalysis (UA) (consider rhabdomyolysis), urine toxicology, serum toxicology, cultures, consider brain computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging and electroencephalography

Close observation and frequent vital signs. Consider malignant catatonias (including NMS- see page 39 for more information) with autonomic hyperactivity and fever (associated with a 50% mortality rate if center untreated)

Supportive care: hydration, nutrition, mobilization, anticoagulation, precautions against aspiration

Discontinue antipsychotics or other possible culprits (e.g. metoclopramide)

Restart recently withdrawn dopamine agonists or benzodiazepines

Institute supportive measures: cooling blanket if hyperthermia or parenteral fluids and antihypertensives or pressors

Suspect medical complications

Treat etiology (see above)

Lorazepam IV, PO, or IM deltoid (first-line agent regardless of cause; 80% effective) 1-2 mg IV initial dose; may repeat q30 min, monitor respiratory rate, up to 20 mg/d (occasionally); switch to PO or nasogastric (NG) 6-20 mg total daily dose for maintenance

Other agents: amantadine 100 mg PO BID; bromocriptine 2.5-5.0 mg PO BID; memantine 5-10 mg PO BID; topiramate 100 mg PO BID

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree