|

|

Noradrenergic (NE), γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), serotoninergic (5-HT), and other neurotransmitter systems have been implicated

Brain areas thought to be involved include limbic system (amygdala), hippocampus, locus ceruleus, and cortical regions

TABLE 3-1 Differential Diagnosis of Anxiety | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Onset after age 35 years

No personal or family history of anxiety disorder

No childhood history of debilitating anxiety, separation anxiety, or phobias

Lack of significant life events leading to or exacerbating anxiety symptoms

Lack of avoidance behavior

Poor response to anxiolytic medications

TABLE 3-2 Approach to the Evaluation of Anxiety | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Prominent generalized anxiety, panic attacks, or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in the setting of substance intoxication or withdrawal

Need confirmation from clinical history, laboratory results, or physical examination that either:

Anxiety developed during or within 1 month of substance intoxication or withdrawal

Substance use is etiologically related to anxiety symptoms

Not occurring exclusively during delirium

Diagnosis should only be made if anxiety exceeds symptoms usually seen in substance intoxication or withdrawal

The person has chronic, excessive worry or anxiety that occurs most days for at least 6 months

It is associated with somatic symptoms, including fatigue, muscle tension, restlessness, sleep disturbance, difficulty concentrating, and irritability

Anxiety is hard to control and causes significant impairment

The person is seen as chronic “worrier” or “nervous person” by others around him or her

3%-8% prevalence rate

2:1 female-to-male ratio

50%-90% have comorbid psychiatric illness

Development of nervousness or worry occurring within 3 months of onset of psychosocial stressor

Remits within 6 months after termination of stressor

Not attributable to bereavement

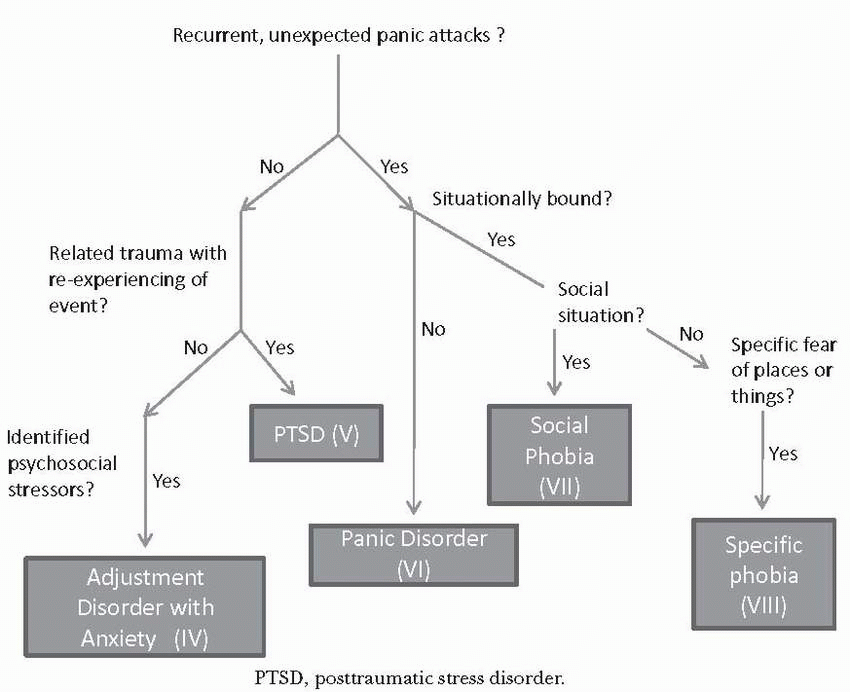

Intense fear, horror, and helplessness experienced after a traumatic event

Trauma was such that patient directly witnessed, experienced, or was confronted with an event that involved actual or threatened death, injury, or threat to physical integrity

Persistent reexperiencing of the event through distressing recollections, dreams, dissociative flashbacks, physiological reactivity, and psychological distress to stimulus cues of event

Persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic event and numbing of general responsiveness (e.g., detachment or sense of estrangement)

Symptoms of hyperarousal are present, including:

Difficulty falling or staying asleep

Irritability or angry outbursts

Difficulty concentrating

Hypervigilance

Exaggerated startle response

Symptoms present for more than 1 month (for symptoms <1 month, consider acute stress disorder)

Recurrent, unexpected panic attacks

Symptoms of panic attacks: overwhelming anxiety or fear that comes on acutely (<10 min) and is accompanied by four or more of the symptoms below:

Chest pain

Palpitations

Derealization or depersonalization

Fear of dying, losing control, or losing one’s mind

Paresthesias

Dizziness or lightheadedness

Shortness of breath

Many individuals may experience limited symptom attacks (e.g., only experiencing one or two of panic symptoms)

Attacks come on suddenly and peak within 10 minutes

Accompanied by more than 1 month of more than one of following:

Anticipatory anxiety (so-called “fear of the fear”)

Corresponding change in behavior (e.g., avoidance)

Worrying about consequences or outcomes of panic attacks

May occur with or without agoraphobia

Agoraphobia

Anxiety caused by being in places or situations from which escape may be difficult or embarrassing or from which help may not be readily available in case of a panic attack

Typically involves clusters of situations outside the home, including being in a crowd; standing in line; being on a bridge; or traveling in a bus, train, or automobile

Situations are avoided or endured with marked distress or anxiety about having panic

The first panic attack must occur unexpectedly (e.g., uncued)

The person may become phobic of particular situation in which panic occurred, but anxiety is from fear of another panic attack. not the situation itself

3% of the general population

Female > male

Average age of onset: 24 years

Potentially increased rate of suicidal ideation and attempts

Excessive anxiety or fear triggered by social situations causing marked impairment

Fear of being publicly scrutinized or humiliated

Panic attacks are a common feature

The patient recognizes that fear is excessive or irrational

The phobic stimulus is avoided or lived through with significant anxiety

Should specify if subtype “performance anxiety” is present

3%-15% prevalence rate

Onset peaks in adolescence

Often comorbid with depression and substance abuse

Irrational, overwhelming fear of a specific situation or object

Fear is recognized as irrational

Avoidance of phobic stimulus is common

Exposure to phobic stimulus can trigger panic attacks

Causes marked impairment

Types of phobias include animals (dogs), natural environment (heights), blood injection, situational (airplanes), and other (fear of choking)

5%-10% of US population

Most common psychiatric disorder among women; second among men

Bimodal distribution of situational phobias: childhood and early adulthood

Start slow: patients with anxiety are very sensitive to somatic side effects

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are first-line agents for most of the disorders

Antidepressant doses used for depression may need to be higher

Older agents such as tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are effective but typically have more side effects

TCAs are not effective for social anxiety disorder

Benzodiazepine are efficacious, fast-acting, and generally well tolerated but have abuse liability

There is a potential concern that benzodiazepines administered in aftermath of trauma may interfere with recovery after trauma

Beta-blockers are sometimes used to reduce autonomic arousal in patients with panic attacks

Beta-blockers are helpful in reducing the performance anxiety subtype but not the generalized subtype of social phobia

Anxiety disorders are effectively treated by many forms of psychotherapy, especially cognitive behavior therapy (CBT)

Cognitive restructuring: restructures catastrophic thinking

Relaxation training: anxiety management strategies

Slow breathing

Muscle relaxation

Behavioral exposure: repeatedly exposing the patient to fearful stimuli to extinguish the conditioned fear response

Supportive therapy is particularly helpful for acute management immediately after the trauma of PTSD

Problems with information recall or learning

One or more of the following problems with cognition:

Aphasia (problems with language)

Agnosia (difficulty recognizing objects)

Apraxia (difficulty executing voluntary movements without motor impairment)

Executive functioning problems (poor planning, abstract reasoning)

May also be associated with:

Poor judgment; disinhibition; hallucinations; delusions; anxiety, mood, or sleep disturbance

TABLE 3-3 Dementia Diagnosis Categories and Representative Examples | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 3-4 Clinical Features of Delirium, Depression, and Alzheimer’s Dementia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Safety of the patient and others takes priority. Use physical restraints or one-on-one supervision when necessary

Consider behavioral interventions

Reorient to environment

Simplify communication

Reassure, distract, and redirect

Identify if delirium is also present

Minimize polypharmacy

Identify and avoid drugs with cognitive side effects

Assess for and treat comorbid medical problems, especially delirium

Start with low doses (one quarter to one half that for normal adults) and increase slowly while monitoring for side effects

Older patients may be more sensitive to medication side effects such as sedation, orthostatic hypotension, anticholinergic side effects, and extrapyramidal side effects (EPS)

No pharmacologic treatment exists for wandering behavior

TABLE 3-5 Approach to the Evaluation of Dementia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 3-6 Dementia Subtypes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 3-7 Suggested Pharmacologic and Somatic Treatments for Symptoms Occurring with Dementia | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Hallucinations, paranoia, and delusions may not require treatment unless they are causing great distress to the patient or potential harm to others

When using atypical antipsychotics, consider the risk-benefit ratio for each patient and talk with patients and their families about the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) black box warning regarding a possible increased risk of death from medication use

Patients with dementia with Lewy bodies (which often co-occurs with Alzheimer’s dementia) are often very sensitive to antipsychotics. (Recall that antipsychotics may cause akathisia and agitation)

TABLE 3-8 Differential Diagnosis of Depression | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

MDE is defined by five or more of the following symptoms, one of which must be depressed mood or anhedonia. All symptoms must occur in the same 2-week period, be present a minimum of most of the day on most days, and result in clinically significant social, occupation, or interpersonal impairment

Depressed mood

Profound loss of interest or pleasure in all or almost all activities (anhedonia)

Profound increase (atypical feature) or decrease in appetite

Insomnia or hypersomnia (atypical feature)

Objective psychomotor hyperactivity or retardation

Decreased energy

Indecisiveness or decreased concentration

Worthlessness or guilt

Recurrent thoughts of death, recurrent suicidal ideation (SI) without a plan, SI with a plan, or suicide attempt (SA)

TABLE 3-9 Approach to the Evaluation of Depression | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Presence of at least one depressive episode

Rule out a history of manic, mixed, or hypomanic episodes; psychotic disorder; and delusional disorder

Modifiers include:

For active MDE: mild, moderate, severe with or without psychotic, melancholic, atypical, or postpartum features

If full criteria for MDE are not present: partial vs. full remission with or without psychotic, melancholic, atypical, or postpartum features

Two thirds of people with MDE contemplate suicide; 10% to 15% commit suicide

There is a 50% recurrence rate after the first episode, a 70% recurrence rate after the second episode, and a 90% recurrence after the third episode

Lifetime risk: women: 20%-25%; men 7%-12%

No socioeconomic or racial correlation

Increased in single people

Circumstances that may increase risk: being single, living in a rural area, divorced, losing a parent before age 11 years, experiencing the death of spouse, unemployment

Defined by depressed mood most of the day for more days than not for 2 years with symptom-free periods not exceeding 2 months during the 2-year period

While the patient is depressed, two of the following must be present:

Increased or decreased appetite

Insomnia or hypersomnia

Fatigue or low energy

Low self-esteem

Indecisiveness or decreased concentration

Hopelessness

Depression resulting in significant clinical impairment but not meeting the criteria for major depression

Occurs within 3 months of a stressful life event and does not persist longer than 6 months after termination of the stressor

Depressive symptoms occurring within 2 months of the death of a loved one are considered normal grief

Certain symptoms after the death may be associated with MDD:

Guilt (not including guilt regarding actions taken or not taken by survivor at the time of death)

Thoughts of death (not including patient feeling he or she would be better off dead or should have died with the deceased person)

Morbid preoccupation with worthlessness

Marked psychomotor retardation

Substantial, prolonged functional impairment

Hallucinations (not including transient seeing or hearing of the deceased person)

There is a 40% remission rate with an adequate single trial with an antidepressant; the majority of the rest of patients show some improvement, but 15% to 30% of patients do not improve after a single adequate trial

The most common reasons for failure are inadequate dosing and inadequate duration

Suggested pharmacotherapy guidelines:

No single antidepressant is universally accepted as more effective than another

Therapy should be chosen based on side effects, drug interactions, dosing schedule, discontinuation symptoms, cost of treatment, and history of effective response (including history of response in a first-degree relative)

Before declaring treatment failure, ensure maximum titration and minimum of 4 to 6 weeks of treatment after achieving the maximum dose (full response is gauged at 8-12 weeks)

Duration of treatment for depression maintenance:

Single episode: treat for a minimum of 6 months after resolution of symptoms or for the length of previous depressive episode, whichever is longer

Multiple episodes: indefinite maintenance

Addressing inadequate treatment response (treatment failure or partial response, defined as a 20% to 25% reduction in depressive symptoms):

Ensure proper dosing and duration of medication

Consider the accuracy of the diagnosis

If there is no response, switch the class of medication

If there is a less than desired response: augmentation with lithium or thyroid hormone (T3)

TABLE 3-10 Suggested Treatment by Depressive Subtype | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 3-11 Differential Diagnosis of Disordered Eating Behaviors | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Significantly low weight (≥15% below expected body weight) in combination with resistance to weight gain, often motivated by excessive concern with thinness or control overeating

Low weight is maintained by dietary restriction but is frequently accompanied by purging and exercise (see Bulimia nervosa)

Lifetime prevalence: 0.9% in women; 0.3% in men

Characterized by regular episodes of binge eating followed by a variety of purging, exercise, and dietary behaviors to prevent weight gain

Lifetime prevalence: 1.0%-1.5% in women

TABLE 3-12 Approach to the Evaluation of Disordered Eating | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Aberrant eating patterns and weight management habits not meeting criteria for AN or BN

The most common presentation of eating disorders

Occurs in 3% to 5% of women age 15 to 30 years

Episodic binge eating without purging, exercise, and dietary behaviors to prevent weight gain

Eating not linked to cues (social, hunger, satiety) that conventionally drive eating

Episodes may be associated with distress and other negative affect

At least three of the following must be present:

Eating more rapidly than normal

Eating until feeling uncomfortably full

Eating large amounts of food when not feeling hungry

Eating alone because of embarrassment of how much one is eating

Feeling disgusted with oneself, depressed, or guilty of overeating

Lifetime prevalence: 3.5% in women; 2% in men

Evaluate the patient’s medical and nutritional compromise

Treat the medical sequelae of undernutrition, purging behaviors, and obesity

Watch for refeeding syndrome caused by low phosphorous (gastric bloating, congestive heart failure (CHF), edema; can lead to respiratory failure, coma, seizures, or death)

Surveillance for and treatment of common and life-threatening complications, such as medical sequela of BN (tooth enamel decay, esophagitis, blistered knuckles) or emergencies such as arrhythmias or hematemesis

Management of obesity-related complications in patients with BED (diabetes, sleep apnea, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease)

Determine energy and micronutrient deficits and protocol for nutritional rehabilitation

The patient may safely gain 0.5 to 2.0 lb per week as an outpatient or up to 3 to 4 lb as an inpatient

Provide vitamin supplementation

Section 12 criteria for admission to inpatient psychiatric facility after medical stabilization: the patient must demonstrate him- or herself to be unable to care for him- or herself, as evidenced by weight below 75% of ideal body weight, electrolyte disturbance (K <3.2), electrocardiographic changes, abnormal vital signs (i.e., bradycardia, low blood pressure, significant orthostatic changes, hypothermia), or indications of suicidality

Patients under 20% of expected weight for their height should be enrolled in inpatient programs

Treatment initially supports nutritional goals and medical and psychiatric stabilization

Family therapy is the treatment of choice for adolescents with AN

CBT and interpersonal therapy (IPT) have been demonstrated effective for BN

Treat common comorbid psychiatric conditions, such as depression and anxiety

Medications that modify appetite: mirtazapine: increase appetite; topiramate: decrease appetite; Meridia: appetite suppressant

Monitor for potential weight gain as a medication side effect (i.e., with atypical antipsychotics)

There are no FDA-approved medications for the treatment of AN

Fluoxetine is FDA approved for treatment of BN (higher dosing, 60-80 mg)

Antidepressant use should not be initiated until weight gain has been achieved because side effects can be more severe in malnourished patients

Bupropion is contraindicated in patients with BN because of an increased risk of seizures

Some data suggest that atypical antipsychotics may have benefits for some AN patients, but this use is off label and has no established efficacy

Use with caution because of the risk for idiopathic and hypokalemiarelated QT prolongation

Antiepileptics have shown some effectiveness anecdotally in patients with BED

Zinc (50-100 mg) has been shown to more rapidly improve weight restoration in patients with AN

primary defense and occur chronically in response to reminders of the original traumatic event or even to relatively minor stressors of everyday living (Howell, 2005).

Daydreaming

Becoming absorbed in a movie or a book

Meditation

“Highway hypnosis” (e.g., being briefly lost in a trance while driving)

Fantasy

Formal or self-induced hypnotic state

Numbing: feeling detached from one’s emotions

Flashback: intrusive immersion in sensory components of a past traumatic experience

Depersonalization: feeling detached from one’s self or looking at one’s self as an outsider would

Derealization: feeling detached from one’s environment or a sense that the environment is unreal or foreign

Amnesia: inability to account for a specific and significant block of time that has passed

Identity confusion: feeling uncertain, puzzled, or conflicted about who one is

Identity alteration: shifting of one’s role or identity, accompanied by changes in behavior

TABLE 3-13 Differential Diagnosis of Dissociative Experiences | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 3-14 Approach to the Evaluation of Dissociation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Requires experience of a traumatic event, occurrence of three to five dissociative symptoms, one reexperiencing symptoms, and marked avoidance and arousal at the time of or shortly after the event

Occurs within 1 month of the traumatic event and persists for at least 2 days

Recognizes dissociative symptoms as frequent sequelae to traumatic exposure

See page 56 for more information

Requires experience of a traumatic stressor, occurrence of one reexperiencing symptom, three avoidance symptoms, and two arousal symptoms for duration of more than 1 month after the event

Does not require dissociative symptoms for diagnosis; however, several dissociative symptoms fall under PTSD diagnostic criteria, including flashbacks, numbing, detachment, restricted affect or absence of emotional responsiveness, and amnesia

One or multiple episodes of memory loss typified by inability to recall important personal information (e.g., one’s identity or significant elements of one’s past)

Occasionally seen in adult-onset traumatic events

The unrecalled personal information is often of a stressful or traumatic nature

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree