Psychiatry and Reproductive Medicine

Reproductive events and processes have both physiological and psychological concomitants. Likewise, psychological states affect reproductive physiology and modulate reproductive events. This chapter examines these bidirectional relationships with the goal of introducing fundamental concepts related to the classic reproductive events, such as menarche, pregnancy, delivery, postpartum, and menopause. The fields of psychiatry and reproductive medicine continue to define the multiple mechanisms by which psyche and soma interact to determine a woman’s gynecological and psychological health. For instance, premenstrual dysphoric disorder—the impairing symptoms and severe mood, cognitive, and behavioral changes that occur in association with the menstrual cycle—exemplifies a somatopsychic disorder in which biological changes occurring in the soma trigger changes in psychological state. In contrast, functional forms of hypothalamic anovulation represent psychosomatic illness that originates in the brain but alters somatic functioning.

REPRODUCTIVE PHYSIOLOGY

The physiological processes associated with menarche, menstrual cycling, pregnancy, postpartum, and menopause occur within the context of a woman’s physiological and interpersonal life, interfacing with psychosocial functioning throughout adolescence, young adulthood, midlife, and late life. The fields of psychiatry and reproductive medicine are just beginning to elaborate the multiple mechanisms by which psyche and soma interact to determine a woman’s gynecological and psychological function. This chapter illustrates how reproductive processes interact with psychosocial events and aims ultimately to improve the approach to both gynecologic and psychiatric treatments.

Menstrual Cycles

Menstrual cyclicity results directly from ovarian cyclicity. Each ovarian cycle starts with the development of a group or cohort of follicles, one of which becomes dominant. The follicles are composed of an oocyte surrounded by granulosa cells, which, in turn, are surrounded by theca cells.

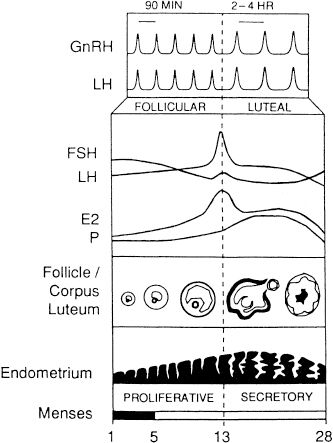

As shown at the top of Figure 27-1, follicular development is initiated by the hypothalamic release of gonadotropin-releasing hormones (GnRH) at a pulse frequency of approximately one pulse every 90 minutes. GnRH stimulates the release of the pituitary gonadotropins, luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). In turn, LH stimulates ovarian theca cells to synthesize and secrete androgens; FSH induces granulosa cell development, including the enzyme aromatase, which converts the thecally produced androgens to estrogens. In the presence of a constant GnRH pulse frequency of one pulse each 90 minutes, the secretion of LH and FSH in the follicular phase will be regulated primarily by estradiol feedback at the level of the pituitary. Rising estradiol concentrations suppress FSH, thereby limiting the number of follicles that become mature oocytes capable of ovulating.

FIGURE 27-1Schematization of the human menstrual cycle. Es, estradiol; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; P, progesterone.

As illustrated in the middle panel of Figure 27-1, when estradiol concentrations rise exponentially to exceed a critical threshold and remain elevated for at least 36 hours, which is the pattern one fully mature follicle produces, an LH surge is triggered and ovulation (release of the ovum from the follicle sac) ensues approximately 36 hours later. Thereafter, granulosa cells transform into progesterone-secreting luteal cells, and the ovulated follicle is then referred to as the corpus luteum, which secretes progesterone.

Figure 27-1 displays the levels of LH, FSH, estradiol, and progesterone throughout the menstrual cycle and corresponding follicular events. The target tissues for ovarian steroids include the endometrium, whose developmental sequence is illustrated along the bottom panel, and the hypothalamic GnRH pulse generator, whose frequency, as indicated in the top right panel, is slowed dramatically by the combination of estrogen and progesterone secreted during the postovulatory or luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. This inhibition of GnRH is followed by decreased secretion of LH and FSH so that new follicular development is prevented until the corpus luteum regresses. As progesterone concentrations decline, GnRH pulsatility increases, and gonadotropin, especially FSH, secretion rises. The phases of the menstrual cycle can be termed follicular and luteal in reference to ovarian events or proliferative and secretory in reference to endometrial events.

PREGNANCY

Biology of Pregnancy

The first presumptive sign of pregnancy is the absence of menses for 1 week. Other presumptive signs are breast engorgement and tenderness, changes in breast size and shape, nausea with or without vomiting (morning sickness), frequent urination, and fatigue. A diagnosis can be made 10 to 15 days after fertilization by testing for human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which is produced by the placenta. The definitive diagnosis requires a doubling of hCG levels and the presence of fetal heart sounds. Transvaginal ultrasound scanning can reveal a pregnant uterus as early as 4 weeks after fertilization, by visualization of a gestational sac.

Stages of Pregnancy

Pregnancy is commonly divided into three trimesters, starting from the first day of the last menstrual cycle and ending with the delivery of a baby. During the first trimester, the woman must adapt to changes in her body, such as fatigue, nausea and vomiting, breast tenderness, and mood lability. The second trimester is often the most rewarding for women. A return of energy and the end of nausea and vomiting allow women to feel better and experience the excitement of starting to look pregnant. The third trimester is associated with physical discomfort for many women. All systems—cardiovascular, renal, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and endocrine—have undergone profound changes that can produce a heart murmur, weight gain, exertional dyspnea, and heartburn. Some women require reassurance that those changes are not evidence of disease and that they will return to normal shortly after delivery—generally in 4 to 6 weeks.

Psychology of Pregnancy

Pregnant women undergo marked psychological changes. Their attitudes toward pregnancy reflect deeply felt beliefs about all aspects of reproduction, including whether the pregnancy was planned and whether the baby is wanted. The relationship with the infant’s father, the age of the mother, and her sense of identity also affect a woman’s reaction to prospective motherhood. Prospective fathers also face psychological challenges.

Psychologically healthy women often find pregnancy a means of self-realization. Many women report that being pregnant is a creative act gratifying a fundamental need. Other women use pregnancy to diminish self-doubts about femininity or to reassure themselves that they can function as women in the most basic sense. Still others view pregnancy negatively; they may fear childbirth or feel inadequate about mothering.

During early stages of their own development, women must undergo the experience of separating from their mothers and of establishing an independent identity; this experience later affects their own success at mothering. If a woman’s mother was a poor role model, a woman’s sense of maternal competence may be impaired, and she may lack confidence before and after her baby’s birth. Women’s unconscious fears and fantasies during early pregnancy often center on the idea of fusion with their own mothers.

Psychological attachment to the fetus begins in utero and, by the beginning of the second trimester, most women have a mental picture of the infant. Even before being born, the fetus is viewed as a separate being, endowed with a prenatal personality. Many mothers talk to their unborn children. Recent evidence suggests that emotional talk with the fetus is related not only to early mother–infant bonding but also to the mother’s efforts to have a healthy pregnancy, for example, by giving up cigarettes and caffeine. According to psychoanalytic theorists, the child-to-be is a blank screen on which a mother projects her hopes and fears. In rare instances, these projections account for postpartum pathological states, such as a mother’s desire to harm her infant, whom she views as a hated part of herself. Normally, however, giving birth to a child fulfills a woman’s need to create and nurture life.

Fathers are also profoundly affected by pregnancy. Impending parenthood demands a synthesis of such developmental issues as gender role and identity, separation or individuation from a man’s own father, sexuality, and, as Erik Erikson proposed, generativity. Pregnancy fantasies in men and wishes to give birth in boys reflect early identification with their mothers as well as the wish to be as powerful and creative as they perceive mothers to be. For some men, getting a woman pregnant is proof of their potency, a dynamic that plays a large part in adolescent fatherhood.

Marriage and Pregnancy

The prospective mother–wife and father–husband must redefine his or her roles as a couple and as an individual. They face readjustments in their relationships with friends and relatives and must deal with new responsibilities as caretakers of the newborn and each other. Both parents may experience anxiety about their adequacy as parents; one or both partners may be consciously or unconsciously ambivalent about the addition of the child to the family and about the effects on the dyadic (two-person) relationship. A husband may feel guilty about his wife’s discomfort during pregnancy and parturition, and some men experience jealousy or envy of the experience of pregnancy. Accustomed to gratifying each other’s dependency needs, the couple must attend to the unremitting needs of a new infant and a developing child. Although most couples respond positively to these demands, some do not. Under ideal conditions, the decision to become a parent and have a child should be agreed on by both partners, but sometimes parenthood is rationalized as a way to achieve intimacy in a conflicted marriage or to avoid having to deal with other life circumstance problems.

Attitudes Toward the Pregnant Woman. In general, others’ attitudes toward a pregnant woman reflect a variety of factors: intelligence, temperament, cultural practices, and myths of the society and the subculture into which the person was born. Married men’s responses to pregnancy are generally positive. For some men, however, reactions vary from a misplaced sense of pride that they are able to impregnate the woman to fear of increased responsibility and subsequent termination of the relationship. A woman’s risk of abuse by her husband or boyfriend increases during pregnancy, particularly during the first trimester. One study found that 6 percent of pregnant women are abused. Domestic abuse adds significantly to the cost of health care during pregnancy, and abused women are more likely than nonabused controls to have histories of miscarriage, abortion, and neonatal death. The reasons for abuse vary. Some men fear being neglected and not having excessive dependency needs gratified; others may see the fetus as a rival. In most cases, however, one finds a history of abuse before the woman became pregnant.

Same-Sex Partnering, Marriage, and Pregnancy

Some lesbian couples decide that one partner should become pregnant through artificial insemination. Societal attitudes may put stress on this arrangement, but if the two women have a secure relationship, they tend to bond strongly together as a family unit. Men in committed gay relationships are fathering children through artificial insemination with surrogate mothers. Recent studies show that children raised in same sex couple households are not measurably different from children raised by heterosexual parents with respect to personality development, psychological development, and gender identity. These children are also not more likely to be gay or lesbian themselves.

Some single, never-married women who do not wish to marry but do want to become pregnant may do so through artificial or natural insemination. Such women constitute a group who believe that motherhood is the fulfillment of female identity, without which they view their lives to be incomplete. Most of these women have considered the consequence of single parenthood and feel able to rise to the challenges.

Sexual Behavior

The effects of pregnancy on sexual behavior vary. Some women experience an increased sex drive as pelvic vasocongestion produces a more sexually responsive state. Others are more responsive than before the pregnancy, because they no longer fear becoming pregnant. Some have diminished desire or lose interest in sexual activity altogether. Libido may be decreased because of higher estrogen levels or feelings of unattractiveness. Avoidance of sex may also result from physical discomfort or an association of motherhood with asexuality. Men with a madonna complex view pregnant women as sacred and not to be defiled by the sexual act. Either a man or a woman may erroneously consider intercourse potentially harmful to the developing fetus and, thus, something to be avoided. Men who have extramarital affairs during their wives’ pregnancies usually do so during the last trimester.

Coitus. Most obstetricians place no prohibitions on coitus during pregnancy. Some suggest that sexual intercourse cease 4 to 5 weeks antepartum. If bleeding occurs early in pregnancy, an obstetrician may prohibit coitus temporarily as a therapeutic measure. Bleeding in the first 20 days of pregnancy occurs in 20 to 25 percent of women and approximately half of that group experience spontaneous abortion. Maternal death resulting from forcibly blowing air into the vagina during cunnilingus has been reported; the deaths presumably result from air emboli in the placental–maternal circulation.

Parturition

Fears regarding pain and bodily harm during delivery are universal and, to some extent, warranted. Preparation for childbirth affords a sense of familiarity and can ease anxieties, which facilitates delivery. Continuous emotional support during labor reduces the rate of cesarean section and forceps deliveries, the need for anesthesia, the use of oxytocin (Pitocin), and the duration of labor. A technically difficult or even painful delivery, however, does not appear to influence the decision to bear additional children.

Men’s responses to pregnancy and labor have not been well studied, but the recent trend toward inclusion of fathers in the birth process eases their anxieties and elicits a fuller sense of participation. Fathers do not parent the same way as mothers, and new mothers sometimes need to be encouraged to respect these differences and view them positively.

Lamaze Method. Also known as natural childbirth, the Lamaze method originated with the French obstetrician Fernand Lamaze. In this method, women are fully conscious during labor and delivery, and no analgesic or anesthetic is used. The expectant mother and father attend special classes, during which they are taught relaxation and breathing exercises designed to facilitate the birth process. Women who have such training often report minimal pain during labor and delivery. Participating in the birth process may help a fearful or ambivalent father bond with his newborn infant.

Prenatal Screening

Prenatal screening for potential or actual fetal malformation is conducted in most pregnant women. Sonograms are noninvasive and can detect structural fetal abnormalities. Maternal α-fetoprotein (AFP) is measured between 15 and 20 weeks, screening for neural tube defects and Down syndrome. The sensitivity of Down syndrome testing is increased when a triple screen is done (AFP, hCG, and estriol). Amniocentesis is indicated for women over 35 years, those with a sibling or parent with a known chromosome anomaly, and those with abnormal AFP or any other risk for severe genetic disorder. Amniocentesis is usually done between 16 and 18 weeks and carries a risk that 1 in 300 women will miscarry after the procedure. In the first trimester, chorionic villus sampling (CVS) can be done, which reveals the same information concerning chromosomal status, enzyme levels, and DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) patterns. With CVS, there is a risk that 1 in 100 women will have a spontaneous abortion after the procedure.

Screening in the first trimester allows women to choose early termination, which may be physically and emotionally easier on the woman. Profound ethical questions are involved in whether or not to abort a fetus with a known defect. Some women choose not to terminate and report a strong loving bond that lasts throughout the life of the child, who usually predeceases the parent.

Lactation

Lactation occurs because of a complex psychoneuroendocrine cascade that is triggered by the abrupt decline in estrogen and progesterone concentrations at parturition. In general, babies should be fed as needed, rather than by schedule. Breast-feeding has many benefits. The composition of breast milk supports timely neuronal development, confers passive immunity, and reduces food allergies in the child. In subsistence-level cultures in which children are allowed to nurse as long as they want (a practice supported by La Leche League, a breast-feeding advocacy group), most babies will wean themselves between ages 3 and 5 if not encouraged by the mother to do so earlier. Women who decide to breast-feed need good teaching and social support, which if lacking may lead to frustration and feelings of inadequacy. Women must not feel pressured or coerced into breast-feeding if they are opposed or ambivalent. In the long term, no discernible difference exists between bottle-fed and breast-fed children as adults.

An incidental finding about lactation is that some women experience sexual sensations during lactation, which in rare cases can lead to orgasm. In the early 1990s a woman who called a help line about such feelings was put in jail and had her infant taken from her on allegations of sexual abuse. Common sense ultimately prevailed, however, and mother and infant were reunited.

Perinatal Death

Perinatal death, defined as death sometime between the 20th week of gestation and the first month of life, includes spontaneous abortion (miscarriage), fetal demise, stillbirth, and neonatal death. In previous years, the intense bond between the expectant or new parent and the fetus or neonate was underestimated, but perinatal loss is now recognized as a significant trauma for both parents. Parents who experience such a loss go through a period of mourning much as that experienced when any loved one is lost.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree