Psychogenic Tremor and Shaking

Joseph Jankovic

Madhavi Thomas

ABSTRACT

The accurate diagnosis of psychogenic movement disorders (PMDs) is based not only on exclusion of other causes, but also on positive clinical criteria. Psychogenic tremor (PT) is the most common of all PMDs. We were able to obtain clinical information on 228 (44.1%) of the patients with PMD, followed for a mean duration of 3.4 ± 2.8 years. Among the 127 patients diagnosed with PT, 92 (72.4%) were female, the mean age at initial evaluation was 43.7 ± 14.1 years, and the mean duration of symptoms was 4.6 ± 7.6 years. The following clinical features were considered to be characteristic of PT: abrupt onset (78.7%), distractibility (72.4%), variable amplitude and frequency (62.2%), intermittent occurrence (35.4%), inconsistent movement (29.9%), and variable direction (17.3%). Precipitants included personal life stress (33.9%), physical trauma (23.6%), major illness (13.4%), surgery (9.4%), or reaction to medical treatment or procedure (8.7%). About a third of the patients had a coexistent “organic” neurologic disorder, 50.7% had evidence of depression, and 30.7% had associated anxiety. Evidence of secondary gain was present in 32.3%, including maintenance of a disability status in 21.3%, pending compensation in 10.2%, and litigation in 9.4%. Improvement in tremor, reported on a global rating scale at last follow-up by 55.1%, was attributed chiefly to “effective treatment by physician” and “elimination of stressors.” The findings from this largest longitudinal study of patients with PT are consistent with other series. We review the clinical features, natural history, prognosis, pathophysiology, and treatment of PT based on our own experience as well as that reported in the literature.

INTRODUCTION

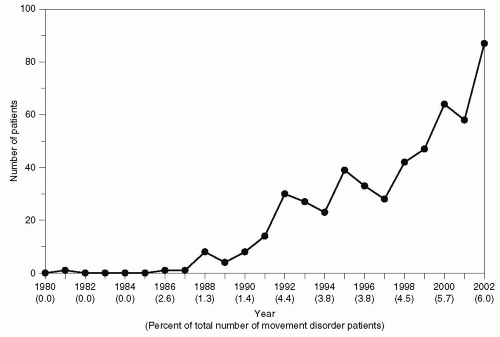

Psychogenic movement disorders (PMDs) are increasingly encountered in specialty clinics. The annual incidence of PMD in the Baylor College of Medicine Movement Disorders Clinic has been increasing at an exponential rate (Fig. 6.1) (1). This apparent increase in the incidence of PMD is probably related to improved recognition of common movement disorders by practicing neurologists; more atypical and difficult to manage disorders, many of which are psychogenic, are now referred to movement disorder specialists. Another reason for the increase may be increased recognition of these disorders by movement disorder specialists.

PT is the most common of all PMDs, accounting for 4.1% of all patients evaluated in our movement disorders clinic at Baylor College of Medicine (Table 6.1).

DIAGNOSIS OF PSYCHOGENIC TREMOR

Many patients with PMD are initially seen by their primary care physicians, and because of associated somatic complaints, are diagnosed as having “functional,” “hysterical,” “conversion,” or “medically unexplained” disorders (2,3). The term “psychogenic,” introduced into the literature by Robert Sommer, a German psychiatrist in 1894, has undergone several mutations since then as reviewed by Lewis in 1972 (4). His definition of the term “psychogenic,” meaning “originating in the mind or in mental or emotional processes; having a psychological rather than a physiologic

origin,” is used in this review (4). We use the term “psychogenic” rather than classify each patient into a specific diagnostic category, such as somatoform, factitious, malingering, or hypochondriacal disorder (5, 6, 7). Although exploration of the psychodynamic underpinning is important in understanding the basis of the PMD in each case, we find this information particularly useful in the management treatment rather than in the diagnostic phase of the evaluation.

origin,” is used in this review (4). We use the term “psychogenic” rather than classify each patient into a specific diagnostic category, such as somatoform, factitious, malingering, or hypochondriacal disorder (5, 6, 7). Although exploration of the psychodynamic underpinning is important in understanding the basis of the PMD in each case, we find this information particularly useful in the management treatment rather than in the diagnostic phase of the evaluation.

Figure 6.1 Annual incidence of PMD at Baylor College of Medicine. (From Thomas M, Jankovic J. Psychogenic movement disorders: diagnosis and management. CNS Drugs. 2004;18:437-452, with permission.) |

TABLE 6.1 PSYCHOGENIC MOVEMENT DISORDERS (BAYLOR COLLEGE OF MEDICINE) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

It is important to emphasize that the accurate diagnosis of PT is based not only on exclusion of other causes, but is dependent on positive clinical criteria, the presence of which should prevent unnecessary investigation. The diagnostic process begins with a careful search in the patient’s history for prior nonorganic disorders, surgeries without identifiable pathology, and excessive somatization. To understand more fully the underlying psychodynamic issues, it is essential to explore prior childhood adverse psychological, sexual, or physical experiences; personality factors; psychiatric history; drug dependence; evidence of a personal encounter or knowledge of a similar illness that could serve as a “model;” recent family life events; work-related or other injury; litigation; and possible secondary gain. We have adopted the following diagnostic classification, initially proposed by Fahn and Williams (8): (a) documented PMD (complete resolution with suggestion, physiotherapy, or placebo), (b) clinically established PMD (inconsistent over time or incongruent with the typical presentation of a classical movement disorder, such as additional atypical neurologic signs, multiple somatizations, obvious psychiatric disturbance, disappearance with distraction, and deliberate slowing), (c) probable PMD (incongruous and inconsistent movements in the absence of any of the other features listed in category b), and (d) possible PMD (clinical features of PMD occurring in the presence of an emotional disturbance).

Psychogenic sensory and motor disorders, such as unexplained paralysis or blindness; false sensory loss; gait and balance problems; and pseudoseizures are well-recognized, but PMDs characterized by hypokinesia (slowness or paucity of movement), hyperkinesias (excessive movements), or ataxia (incoordination of movement) are among the most common forms of psychogenic neurologic disorders. The most common PMD is psychogenic tremor (PT), defined as tremor or shaking not fully explained by organic disease (negative or exclusionary criteria) and exhibiting characteristics, described later, that make the movement incongruous with any organic tremor (positive criteria).

The diagnosis of PT is facilitated by various clues based on historical information and examination. The phenomenology of PT ranges from rest, postural, and kinetic tremor to bizarre “shaking” or repetitive “jerking” resembling myoclonus (9) or seizures (pseudoseizures) (10,11). Although the tremor usually involves the limbs, some patients exhibit shaking of the head and face. When the facial movement is confined to only one side of the face, it may resemble hemifacial spasm (12). Most patients exhibit all three types of tremor—rest, postural, and kinetic—to a variable degree. The duration of the tremor varies considerably among and within patients. PT may be classified according to duration into three types: (i) long duration (either continuous or intermittent) tremor, (ii) short-lived or paroxysmal tremors lasting less than 30 seconds, and (iii) continuous tremor, with superimposed short paroxysmal episodes (13). Other clues to the diagnosis of PT include selective disability; spontaneous and intermittent remissions; trigger by injury, stress, loud noise, or other precipitants; poor response to medication; and recovery with psychotherapy.

On examination, PT is typically characterized by rhythmical shaking incongruous with known tremor types; variability of frequency, amplitude, direction, and location of movement; distractibility; entrainment; suppressibility; and deliberate slowing. In “the shortest paper,” Campbell (14) pointed out that nonorganic tremors tend to decrease when attention is withdrawn from the affected area. Distractibility is defined as marked reduction, abolishment, or a change in amplitude or frequency of tremor when the patient is concentrating on other mental or motor tasks, such as repetitive alternating movements or a complex pattern of movements in the opposite limb. We often ask the patient to perform and repeat the following motor sequence of opposition of second, fifth, and third finger to the thumb of the contralateral hand. Entrainment is demonstrated when the original frequency (and amplitude) of tremor is changed in an attempt to match the frequency (and amplitude) of the repetitive movement performed by the patient volitionally or passively in the contralateral limb or tongue. In addition, we test for muscle tone, and specifically for evidence of active resistance against passive range of movement.

Some patients with PT may also have associated parkinsonism (15). In addition to rest tremor, patients with psychogenic parkinsonism demonstrate other tremor types; deliberate slowing; and resistance against passive movement, frequently varying with distraction. They may have a stiff gait and decreased arm swing when walking, often involving only one arm, which may or may not persist while running. Response to postural stability testing is often very inconsistent and many patients demonstrate an extreme response to even minor pull, flinging their arms, even though the arms may have been previously severely bradykinetic. Although they may retropulse, they almost never fall.

PT can affect any part of the body, but typically it causes shaking of the head, arms, and legs, often to a variable degree with changing anatomic distribution. Voice tremor may also be a manifestation of PT. Even palatal tremor has been reported to be a form of PT (16).

Physical examination of patients with PT may reveal other neurologic findings including false weakness, midline sensory split, lateralization of tuning fork, Hoover sign, pseudoclonus (clonus with irregular, variable amplitude), pseudoptosis (excessive contraction of orbicularis, with apparent weakness of frontalis), pseudo waxy flexibility (maintenance of limb in a set position, and inability to change this position), and convergence spasm (bilateral or unilateral spasm of near reflex, with intermittent episodes of convergence with miosis, and accommodation) (17). Another useful clue to the presence of PT is the apparent lack of concern, termed “la belle indifférence,” with dissociation from the tremor and the “disability” it causes. Some patients even smile or laugh while they relate their history of the disability that the tremor causes, as well as during examination and videotaping. On the other hand, some patients demonstrate an inordinate amount of effort in performing manual tasks accompanied by sighing, facial grimacing, and exhaustion. They may also embellish or exaggerate the symptoms and show signs of panic, such as tachycardia, hyperventilation, and perspiration.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree