Psychological Evaluation in the Psychiatric Context

Psychological evaluation in the psychiatric context generally refers to measurements from psychological testing (in addition to the utilization of information from the history and traditional mental status examination), made for the purpose of helping delineate and clarify a patient’s psychopathology. Psychological testing is frequently requested to address specific clinical issues such as the patient’s need for hospitalization, personality factors complicating Axis I symptoms, the possible presence of malingering, identification of major therapeutic issues, the patient’s potential for suicide, his or her primary defense mechanisms and coping style, and the most appropriate discharge options. The child psychiatrist may need to rule out neurodevelopmental disorders such as mental retardation with cognitive testing. Questions a psychiatrist may ask in a neuropsychological referral are typically related to the role of possible central nervous system dysfunction in a patient’s pathology and its impact on daily functioning. For example, does a patient have dementia or pseudodementia, is a patient’s behavioral or emotional dyscontrol the result of personality factors or impaired central nervous system mechanisms that modulate such reactions, and what is the extent of organic damage and associated cognitive impairment? In addition to clarifying the diagnosis and assisting in treatment planning, psychological testing can play an important role in outcome assessment by helping to document the effectiveness of the treatment provided to a given patient.

The psychiatrist’s ability to call upon and utilize psychological consultation on complex clinical cases in the course of practice leads to many diagnostic advantages over relying upon interview and observations alone, particularly in today’s health care environment that emphasizes documentation. Further, having an understanding of a patient’s personality structure, amenability to treatment, and verbal skills, for example, are extremely useful in deciding whether psychosocial treatments or pharmacological treatment alone would be the preferred treatment modality. The demonstration of treatment effectiveness by measurably positive changes on symptom report scales is important documentation for insurance companies, managed care corporations, and patient consumers. The measurement of a patient’s tendency to deliberately exaggerate or to experience somatoform symptoms is often critical in the medicolegal context. Similarly, the measurement of cognitive skills and deficits adds a dimension to the psychiatrist’s understanding of the patient’s abilities, whether it be the identification of precocity in a preschooler or dementia in an aged professional who is reluctant to retire despite complaints from clients and business partners.

The selection of tests to address given referral questions is determined according to whether they satisfactorily meet key psychometric standards. Psychological tests are typically norm-referenced, that is, the score of an individual patient is compared to the average of the standardization sample, the group of persons to whom the test was initially administered, and who were carefully chosen as being representative of the population of interest (e.g., patients with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder). The test procedures themselves are also standardized. While informal bedside testing can be adapted to one’s personal style and has the flexibility of incorporating items specific to the referral questions, standardized testing implies uniformity of test administration, scoring, and interpretation.

Standardization contributes to the test’s reliability, that is, it must be internally consistent and produce the same or similar results if given to the same individual at different times. For example, if a medical school applicant scores in the 98th percentile on the Medical College Admissions test (MCAT) on Saturday and in the 60th percentile on Monday using the same test version or an equivalent form, the measure is said to be unreliable because little confidence can be put in either score. The useful psychological test must ultimately also have validity, the most important criterion for a test: the degree to which the test actually measures what it claims to be measuring. The validity of a test can be assessed in a number of different ways. It can be measured against an external, well-accepted criterion (criterion validity). For example, with regard to its criterion validity, does the MCAT score actually predict medical student performance as measured by relevant external criteria, such as grades, faculty evaluations, and successful completion of training? Does a test for obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) correctly identify most patients who have been diagnosed as meeting OCD criteria by multiple raters? Criterion validity is assessed by calculating the test’s sensitivity (its ability to correctly classify a patient as having the condition of interest), and its specificity (its success in correctly classifying patients without the condition). Another type of validity, content validity, involves a systematic analysis of the individual items comprising the test in order to determine how well the items sample the behavior domain under study. For example, a measure of depression should consist of items that sample all major aspects (e.g., cognitive, physiologic, and behavioral) of the construct with respect to their relative importance. A test must also have ecological validity, the degree to which the test genuinely reflects cogent, real-world realities and behavior. For example, an elderly patient may perform very poorly on a test of mental arithmetic skills, but the score may bear little relationship to her ability to balance a checkbook if she can compensate for her concentration problems by using the aid of pencil and paper. The utility of a test is another key characteristic, referring to its unique usefulness in answering the relevant referral questions and contributing to the desired outcome. The tests described in this chapter are among those that have withstood scrutiny over time and demonstrated their utility in psychiatric practice.

Personality and Behavioral Assessment

Interest in personality assessment predates the scientific advances in psychological testing. Throughout the ages, people have evaluated their own conduct and the actions of others for the purpose of understanding and predicting behavior. Scientific personality testing has its origins in the study of individual differences through psychological measurement.

Contemporary personality and behavior measures are typically described as being either objective or projective in type. The use of the term “objective” implies that responses are objectively scored and interpreted according to normative data. Examples of the former include comprehensive objective personality tests, behavioral rating scales, and actuarial assessment techniques. We have selected examples of these types of objective personality and behavioral instruments for discussion, as they are the ones the psychiatrist is most likely to encounter in clinical practice. That is, when referring patients for personality testing, there will be a greater likelihood that many of the following will be administered and discussed in the psychologist’s report. There will also be a parallel discussion of projective tests.

Comprehensive personality tests are structured paper-and-pencil self-report instruments whose items are answered in a standard format (e.g., true–false). Usually the patient is the respondent, though some tests utilize the input of significant others. They are scored in a quantitative manner, and resulting numerical scores are subjected to statistical analyses. Typically, a profile is generated that contrasts the patient’s scores with those of the normative sample. Normative data are provided in the test manual, as are reliability and validity information.

The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2) is the most frequently used personality inventory in clinical practice. In the 1930s, psychiatrists and psychologists had to rely almost exclusively on interview procedures to assist them in making clinical decisions. Starke Hathaway and Charley McKinley, a psychologist–psychiatrist collaborative team at the University of Minnesota, published the original MMPI in 1943. It was developed entirely from an empirical perspective, with response items chosen solely on the basis of their ability to distinguish among cohorts of psychiatric patients with given disorders. This 566-item true-false test was designed to yield 10 clinical subscales: Hypochondriasis, Depression, Hysteria, Psychopathic Deviate, Masculinity–Femininity, Paranoia, Psychasthenia, Schizophrenia, Hypomania, and Social Introversion. For ease of communication, each scale was given an associated number. For example, Hypochondriasis = 1, Depression = 2, and so forth. Psychologists typically refer to these numbers when discussing an MMPI profile among themselves, as many scale names are clinically outdated (e.g., Psychasthenia). In addition, there are multiple validity scales available which measure the respondent’s test-taking attitude (e.g., defensiveness, exaggeration of symptoms). Sets of items selected for inclusion in the test’s final version differentiated a specific clinical sample (e.g., depressed patients on the Depression subscale) from the normal subjects who comprised the standardization group.

The MMPI was revised in 1989 as the MMPI-2, which consists of 567 self-descriptive statements. In the revision, several original items were reworded or deleted, and statements focusing on suicide, substance abuse, and related matters were added. The revised version also includes a standardization sample that is more representative of the U.S. population (based on census data). In 2003, an extensive project was completed that restructured the clinical scales of the MMPI-2 and anchored them in an empirically derived factor structure. Another extensive revision of the MMPI-2 is reportedly soon to be published, reducing its length and revising the primary clinical scales. These changes guarantee that the MMPI-2 and its successors will continue to play an important role in the assessment of psychopathology, though its evolution as an instrument raises many questions about validity and utility that will need to be addressed by careful research.

Interpretation of the MMPI-2 is based primarily on a profile analysis consisting of two or three highest scale elevations. Scales with T scores of 65 or above are considered clinically significant. Abnormally low scores are interpretable. Numerous books are available to help the clinician interpret specific code types. The basic profile form of a hand-scored MMPI-2 is shown in Figure 6–1. The patient’s profile suggests a depressive disorder with possible cognitive changes or even psychotic involvement (elevated Depression and Schizophrenia scales) in an individual who is overly dependent, self-centered, and naïve about their own feelings and motivations (elevated Hysteria scale).

Figure 6–1.

Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2) Profile for Basic Scales. (Copyright © 1989 the Regents of the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved. “MMPI-2” and “Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2” are trademarks owned by the University of Minnesota. Reproduced by permission of University of Minnesota Press.)

The Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI) was constructed in 1991 by Leslie Morey, then a professor of psychology at Vanderbilt University, with the goal of closely corresponding to contemporary psychiatric concepts and diagnostic nomenclature, such as found in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The test consists of 344 items answered on a four-point Likert-type format: totally false, slightly true, mainly true, and very true. In addition to the 11 clinical scales (diagnosis), there are 5 treatment consideration scales (prognosis), 2 interpersonal scales (social support), and 4 validity scales. The clinical scales are Somatic Complaints, Anxiety, Anxiety-Related Disorders, Depression, Mania, Paranoia, Schizophrenia, Borderline Features, Antisocial Features, Alcohol Features, and Drug Features. An important feature of the PAI scales is that they are further divided into subscales that reflect specific components or subtypes of a given disorder. For example, a patient’s specific manifestation of anxiety may be as excessive worry and concern (i.e., cognitive) rather than trembling hands (e.g., physiologic). The treatment scales (Suicidal Ideation, Treatment Rejection, Nonsupport, Stress, Aggression) also provide the clinician with pertinent information for treatment planning, an especially useful feature of this test.

The MMPI-2 and PAI are two important objective personality inventories for diagnostic classification and treatment planning. The empirically developed MMPI-2 is used primarily for spotlighting acute psychiatric (Axis I) issues and for identifying patients’ psychopathological patterns that may not be explicitly apparent to either the patient or the clinician. The PAI is a more “face-valid” test; that is, the scales correspond, often very explicitly, with current psychiatric (DSM) conceptions of Axis I disorders and Axis II personality disorder criteria. Though designed to be an improved MMPI-2, most clinicians who have used both have found each to contribute uniquely useful information to the assessment process, as reflected by the immense popularity of both instruments.

There are several advantages to using comprehensive personality measures. They are relatively simple to administer. The arduous task of data entry, scoring, and calculating scales may be accomplished by computer. Test manuals provide standardization and psychometric information (e.g., validity and reliability data) for the user, as well as guidance in clinical interpretation. Comprehensive personality instruments also have limitations. They are primarily behavioral in content and may provide inadequate information about the respondent’s underlying motives or psychodynamics. For example, two patients may produce identical profiles indicating that they feel depressed and anxious. In one case the symptoms may be the result of acute situational stress (e.g., financial reversals), whereas in the other case, the symptoms may be long-standing and connected to historical issues, such as unresolved childhood trauma. Further, the prescribed objective response method (e.g., true-false or four-point scale) prevents patients from elaborating or qualifying their responses.

Behavioral rating scales are objective scales that may be self-administered or, especially when used with children or severely impaired individuals, rely on the reports of knowledgeable informants. These scales usually focus upon a single disease construct (e.g., depressive symptoms, obsessive–compulsive symptoms, PTSD symptoms) or upon a set of specific behaviors of interest in a given population, such as ratings of childhood behavioral problems. The scale’s scores are then typically compared to normative data in the form of averages or cutoff points identified by research as optimal in predicting a given criterion. Behavior rating scales tend to be more focused on a given set of behaviors or symptoms, or are developed on a given subpopulation (e.g., children, PTSD victims) than comprehensive personality tests. As such, they may be more limited in scope, but may assist the clinician in specifically elucidating a patient’s clinical presentation in a more complete fashion.

The chapters in this volume on child assessment reference some of the most widely used comprehensive child behavior rating scales (e.g., Child Behavior Checklist). Adaptive behavior rating scales for children and adults, such as the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale, provide standardized procedures for assessing functional abilities, key to the assessment of mental retardation, and other developmental disorders. These tests, and ones like them, are in reality collections of multiple behavior rating scales that are conormed on a single population and designed to tap several domains of behavior.

One of the most widely used rating scales is the Beck Depression Inventory, now in its second version. Though often used to aid in diagnosing depression, its major utility is in measuring the severity of self-reported depressive symptoms, and in describing the particular manifestation of depression in a given patient. It contains self-rating items of all the DSM criteria of depression, as well as other changes commonly experienced in depressive patients. A simple glance at the rating form yields a wealth of information, such as the overall severity of the symptoms, and whether the patient’s symptoms are more physiological, cognitive, or mood-oriented in nature.

Many advantages of behavioral rating scales have already been mentioned. They represent powerful tools in assessing the severity of psychiatric disorders and in illuminating the nature and characteristics of many behavioral syndromes. The sheer wealth of scales is almost bewildering: for nearly any given disorder, the clinician or researcher will have an array of well-researched instruments from which to choose. Their utility is in great demand whenever objective, repeatable, quantifiable data are required to assess patients’ progress in treatment, the efficacy of new research treatments, or the measurement of quality outcomes.

Their very specificity unfortunately contributes to some of their disadvantages. By focusing only on a given syndrome or symptom cluster, the use of a targeted rating scale may serve to mask initial diagnostic errors because symptoms from other syndromes may not be assessed. Perhaps their greatest weaknesses are apparent in the forensic assessment context. In most cases, the scales are so transparent (“face-valid”) that it is easily apparent to the respondent exactly what disorder or set of behaviors is being assessed by the scale. Few of the measures have acceptable validity indexes to identify the impact of potentially defensive responding or malingering. Even unintentional false reporting, such as by a frustrated parent who is at wit’s end over a child’s disruptive behavior, or a parent who is determined to cast their child’s conduct problems in an acceptable light by over-endorsing depressive symptoms, can muddy the conclusions. In sum, the utility of these scales is quite limited in the forensic realm, and are best used in the context of a comprehensive, multimodal assessment.

Actuarial measures are assessment methods based purely on given patient characteristics, demographic information, and historical data that are mathematically combined to make probabilistic classifications of patients (e.g., risk of violence or likelihood of responding favorably to a given type of treatment). However, for many clinicians, the thought of basing treatment or placement decisions on actuarial descriptors or cut scores may seem foreign, if not repellent. Yet there are psychiatric evaluation contexts that sometimes require the input of such techniques. For example, the psychiatrist who assesses a patient’s suicide risk by asking about history of prior attempts, current plans, intentions, means, age, level of stress, and religiosity is in fact using an informal analogue of an actuarial process to make a critical determination. Attempts to more rigorously codify systems for assessing suicidal risk have met with some success (e.g., Suicide Potential Scale).

Actuarial techniques are most often appropriate in clinical situations in which a decision must be made in one direction or the other, regardless of the quality of the data, because of the gravity of the potential outcomes. In addition to suicide risk, the most common situations requiring an estimate of risk usually revolve around violent behavior. Multiple actuarial rating systems have been researched and developed in this area, including aids to the evaluator involved in assessing risk of sexual reoffending (e.g., STATIC-99), risk of suicide (e.g., Suicide Potential Scale), and risk of violent reoffending in individuals with a known history of violence (e.g., Violence Risk Assessment Guide, or VRAG).

The latter technique, the VRAG, is the product of an extensive research program on violent offenders in a maximum-security institution in Ontario. The VRAG represents a typical actuarial procedure. The patient is rated on several static dimensions, such as the nature of their offense, the presence of a psychotic disorder, age, presence of childhood conduct disorder, and several other variables. The patient is also subjected to an interview with the Hare Psychopathy Checklist, a semistructured interview technique designed to identify the degree of a patient’s psychopathy, or tendency to demonstrate personality characteristics shown to be related to serious acts of violence (see Table 6–1).

Superficial | Glib, slick, and smooth in social interactions. |

Grandiose | Possessing an inflated sense of importance and self-assuredness |

Lack of remorse | Unconcerned about others’ distress, disdainful of victim’s feelings |

Lack of empathy | Unable to place oneself in the inner world of another person, callous |

Pathological conniving | Deceitful, shrewd, cunning, manipulative |

Impulsive | Acts without considering consequences, reckless, displays anger with little provocation |

Sensation seeking | Pathological need for excitement and a sense of risk |

Lack of responsibility | Parasitic lifestyle, promiscuous sexual behavior, failure to meet obligations |

Lack of goals | Aimless lifestyle, no sense of purpose |

Juvenile delinquency | Pattern of rights violations beginning in childhood or adolescence |

Adult sociopathy | A diverse pattern of adult antisocial behaviors, career criminality |

The patient’s overall score is then compared to a sample of offenders with a known recidivism rate, and a probability value of future reoffending is assigned. While marked by a large error rate, this method is considerably superior to nonquantitative clinical judgments of violence risk made by psychologists and psychiatrists. This and similar methods are now commonly used in forensic consultation, and have been accepted for use by the courts in multiple court decisions.

The advantages to the psychiatrist in utilizing these actuarial methods, when available, are considerable. In addition to providing a check on personal biases and minimizing the inherent inaccuracy of general impressions based on a global impression of the patient, professional risk issues are minimized. By definition, these techniques represent the standards generally accepted by the mental health community, and thus would presumably serve as a powerful protective measure in the unhappy event of liability litigation following a patient committing a violent act. Disadvantages include the fact that the error rates of these methods, though superior to clinical judgment, remain very high. Presumably, many more predictive factors or combinations thereof need to be identified in order to reduce the error rate. Such methods also do not usually take into account dynamic factors such as availability of treatment, compliance with treatment, intrapersonal changes due to the consequences of past acts of violence, or the impact of supervision and scrutiny, to name a few. Consequently, actuarial analysis is best employed as an adjunct to, not a replacement for, comprehensive psychological or psychiatric assessment.

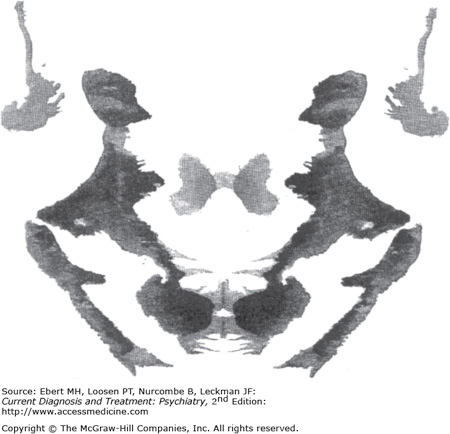

As opposed to objective personality testing, in projective personality testing, the individual is provided unstructured test stimuli (e.g., inkblots, incomplete sentences, pictures of human figures) and required to give meaning to them. The theoretical assumption is that the patient’s responses reflect primarily a “projection” of the individual’s inner needs, motivations, defenses, and drives. That is, tests are intended to elicit a projection of unconscious material from the subject’s inner life. In theory, the manner in which the patient organizes and perceives the ambiguous test stimuli reveals something about his or her distinctive personality. There are objective scoring systems for some projective tests, such as the Exner Comprehensive Scoring System, one of the most sophisticated and widely used for the Rorschach. However, some clinicians prefer to make psychodynamic interpretations from the thematic content of the patient’s Rorschach responses, arguing that they are achieving a much richer understanding of the patient than that provided through more sterile numerical analysis of the person. Proponents of objective personality inventories often criticize their counterparts who favor projective testing for not meeting higher standards of validity, reliability, and standardization. Many clinicians, however, utilize a test battery of both objective and projective tests when performing a psychological workup on a patient. Such a strategy will likely result in a more comprehensive evaluation of a patient and provide more confidence in replicated findings from different types of test stimuli. Three of the projective tests that have stood the proverbial “test of time” are the Rorschach Inkblot Test, the Thematic Apperception test (TAT), and the Sentence Completion test (SCT).

The Rorschach Inkblot Test was the creative effort of a Swiss psychiatrist, Hermann Rorschach, who first published the test in 1921. Out of several hundred inkblot configurations, he selected 10 cards because of the variety of responses they elicited. Five of the bilaterally symmetrical inkblots are achromatic, two have additional spots of red, and three combine several colors (Figure 6–2).

During the test administration, the examiner asks the patient what each card looks like (i.e., “What might this be?”). The examiner then records the patient’s responses verbatim, the time it takes to generate responses, and any nonverbal reactions. After the responses are compiled, the examiner asks the patient to go through the cards again. This is referred to as the inquiry phase. In the latter phase, the examiner is attempting to identify the factors influencing the response—what parts of the blot are used and what features made the blot look a certain way (e.g., color, movement, texture, shading, and form). All of these factors are interpretable. For example, perception of movement (e.g., the percept of a bird in flight) is considered to relate to the richness of an individual’s fantasy life. The form determinant (e.g., how closely the response corresponds with the selected area of the inkblot) is believed to indicate an individual’s reasoning powers and reality testing. Persons with good psychological functioning tend to have refined and differentiated perceptions, whereas the perceptions of psychologically impaired persons generally fit poorly with the form of the blot associated with their response. Color responses are believed to reflect the emotional life of the respondent. For example, pure color responses (i.e., the blot color itself stimulates the respondent’s associative process) are considered to reflect an individual with poorly integrated emotional reactions. Location choice (e.g., the area of the blot where the respondent associates his or her response) is also considered to reflect something about one’s personality. For example, an emphasis on very small details is considered to reflect an individual who has a very critical attitude or is overly concerned with trivialities.

Responses are analyzed in terms of the number that fall into various categories (e.g., movement, form, location), the normative frequency of these categories for different clinical groups, and the relationships among determinants (i.e., ratios such as percentage of conventional form). Psychodynamically oriented examiners also interpret the content of responses in terms of symbolic meaning (e.g., perception of an island may reflect a sense of isolation). When interpreted within the respondent’s specific experiences, the latter analyses are believed to reveal a great deal about an individual’s unique personality style.

A number of Rorschach scoring and interpreting systems have been developed since its inception. Irving Weiner and John Exner have attempted to put contemporary Rorschach assessment on a psychometrically sound basis. For instance, the Exner Comprehensive Scoring System emphasizes structural rather than thematic content of responses. This complex scoring system involves categorizing responses in an objective manner by converting them into ratios, percentages, and other indices. Interpretations are primarily data based rather than theoretically based. The Exner system has been well received by the current generation of Rorschach testers whose graduate training has emphasized the importance of psychometric standards in assessment.

The TAT was developed in 1943 by Harvard psychologist Henry Murray. The test consists of 29 pictures and one blank card. The cards have recognizable human figures (Figure 6–3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree