Psychosomatic Medicine

13.1 Introduction and Overview

13.1 Introduction and Overview

Psychosomatic medicine has been a specific area of concern within the field of psychiatry for more than 50 years. The term psychosomatic is derived from the Greek words psyche (soul) and soma (body). The term literally refers to how the mind affects the body. Unfortunately, it has come to be used, at least by the lay public, to describe an individual with medical complaints that have no physical cause and are “all in your head.” In part due to this misconceptualization, the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), in 1980, deleted the nosological term psychophysiological (or psychosomatic) disorders and replaced it with psychological factors affecting physical conditions (see Section 13.5), nor has the term reappeared in subsequent editions, including the latest edition (DSM-5). Nonetheless, the term continues to be used by researchers and is in the title of major journals in the field (e.g., Psychosomatic Medicine, Psychosomatics, and Journal of Psychosomatic Research). It is also used by the two major national organizations in the field (the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine and the American Psychosomatic Society) as well as international organizations (e.g., the European Association for Consultation Liaison Psychiatry and Psychosomatics). In 2003 the American Board of Medical Specialties and the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology approved the specialty of psychosomatic medicine. That decision recognized the importance of the field and also brought the term psychosomatic back into common use.

HISTORY

As Edward Shorter discusses in detail in his summary of the history of psychosomatic illness, ways of presenting illness vary over history, because patients unconsciously select symptoms that are thought to represent true somatic illnesses. As a result, psychosomatic presentations have varied over the course of recent history. Prior to 1800, physicians did not conduct clinical evaluations and could not distinguish somatic from psychogenic illness. As a result, the diagnoses of hysteria and hypochondriasis could easily be made in the presence of true medical illnesses and did not suggest any specific disease presentations.

Sigmund Freud was the principal theoretician to bring psyche and soma together. He demonstrated the importance of the emotions in producing mental disturbances and somatic disorders. His early psychoanalytic formulations detailed the role of psychic determinism in somatic conversion reactions. Using Freud’s insight, a number of workers in the early decades of the 20th century tried to expand the understanding of the interrelationship of psyche and soma. The influence on adult organ tissue of various unresolved pregenital impulses was proposed by Karl Abraham in 1927, the application of the idea of conversion reaction to organs under the control of the autonomic nervous systems was described by Sándor Ferenczi in 1926, and the attaching of a symbolic meaning to fever and hemorrhage was suggested by Georg Groddeck in 1929.

In the 20th century, somatization symptoms changed from predominantly neurologic (e.g., hysterical paralysis) to other symptoms such as fatigue and chronic pain. Edward Shorter attributes this change to three causes: (1) improvements in medical diagnostic techniques made it easier to rule out organic causes for neurologic disease; (2) the central nervous system (CNS) paradigm faded; and (3) social roles changed (e.g., the disappearance of the historical notion that “weak” women would be expected to have fainting spells and paralysis).

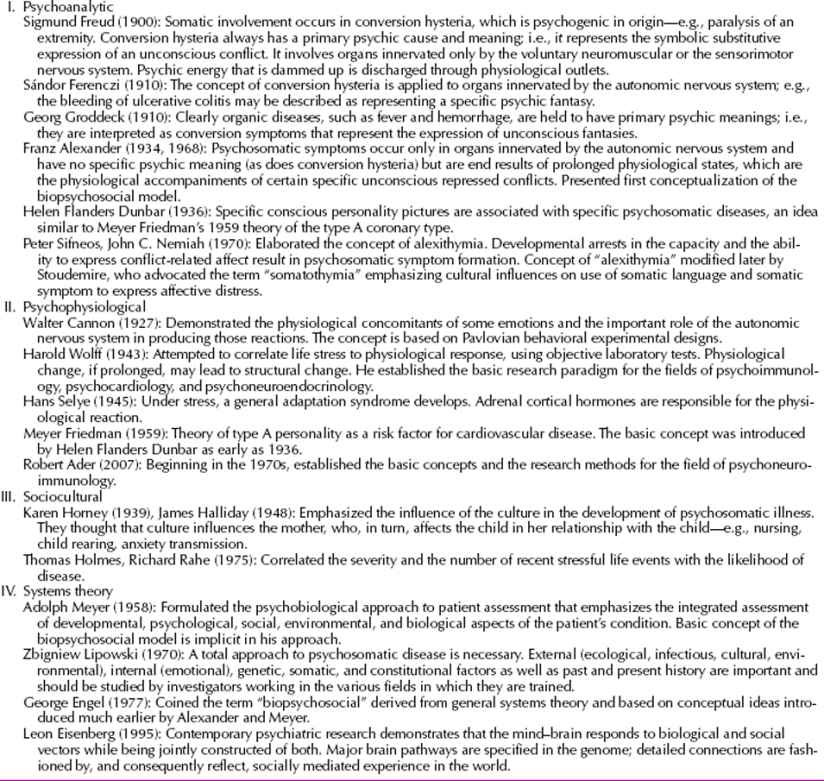

Although hysterical neurologic symptoms have remained relatively less common in the 21st century, CNS explanations of chronic pain and fatigue are gaining prominence. For example, functional brain research has demonstrated brain dysfunction and possibly genetic contributions among some individuals with fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome. Those syndromes, while still thought by some to represent somatization variants, are currently established medical diagnoses. The major conceptual trends in the history of psychosomatic medicine are outlined in Table 13.1-1.

Table 13.1-1

Table 13.1-1

Major Conceptual Trends in the History of Psychosomatic Medicine

CURRENT TRENDS

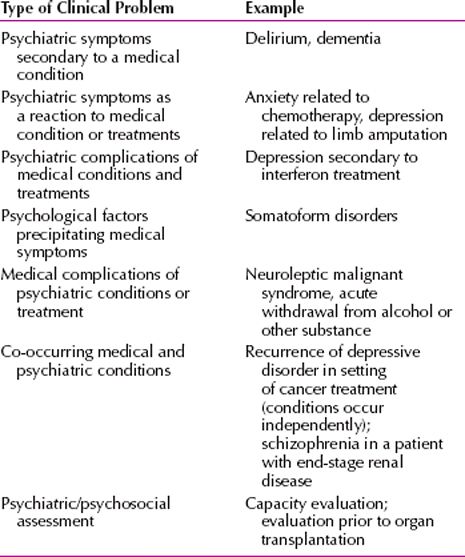

The practice of psychosomatic medicine has evolved considerably since its early clinical origins and has come to focus on psychiatric illnesses that occur in the setting of physical health care. In large part this evolution has occurred as a result of the increased complexity of medicine, the increased understanding of the relationship of medical illness to psychiatric illness, and the greater appreciation of mind and body as one. A key outcome of this has been the granting of subspecialty status for psychosomatic medicine. Clinical care is now delivered in a variety of health care settings and utilizes an ever expanding set of diagnostic tools, as well as many effective somatic and psychotherapeutic interventions. Research in the area has progressed to include a greater understanding of the relationship between chronic medical conditions and psychiatric disorders and has examined the pathophysiologic relationships, the epidemiology of comorbid medical and psychiatric disorders, and the role specific interventions play in physiologic, clinical, and economic outcomes (Table 13.1-2).

Table 13.1-2

Table 13.1-2

Summary of Clinical Problems in Psychosomatic Medicine

Psychiatric morbidity is very common in patients with medical conditions, with a prevalence ranging from 20 to 67 percent, depending on the illness. Patients in the general hospital have the highest rate of psychiatric disorders when compared with community samples or patients in ambulatory primary care. For example, compared with community samples, depressive disorders in the general hospital are more than twice as common, and substance abuse is two to three times as common. Delirium occurs in 18 percent of patients. Similarly, increased rates are seen in primary and long-term care.

Psychiatric morbidity has serious effects on medically ill patients and is often a risk factor for their medical conditions. It is well established that depression is both a risk factor and a poor prognostic indicator in coronary artery disease. Psychiatric illness worsens cardiac morbidity and mortality in patients with a history of myocardial infarction, diminishes glycemic control in patients with diabetes, and decreases return to functioning in patients experiencing a stroke. Depressive and anxiety disorders compound the disability associated with stroke. In the context of neurodegenerative disease such as Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s, depression, psychosis, and behavioral disturbances are significant predictors of functional decline, institutionalization, and caregiver burden. Hospitalized patients with delirium are significantly less likely to improve in function compared with patients without delirium. Delirium is associated with worse outcomes after surgery, even after controlling for severity of medical illness.

In addition, depression and other mental disorders significantly impact quality of life and the ability of patients to adhere to treatment regimens (e.g., in patients with diabetes mellitus). Psychiatric disorders are linked to nonadherence with antiretroviral therapy, adversely affecting the survival of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients. Psychiatric disorders worsen the prognosis and quality of life of cancer patients. Psychiatric disorders are also linked to nonadherence with safe sex guidelines and with use of sterile needles in HIV-infected injection drug users, thus having major public health implications.

EVALUATION PROCESS IN PSYCHOSOMATIC MEDICINE

Psychiatric assessment in the medical setting includes a standard psychiatric assessment as well as a particular focus on the medical history and context of physical health care. In addition to obtaining a complete psychiatric history, including past history, family history, developmental history, and a review of systems, the medical history and current treatment should be reviewed and documented. A full mental status examination, including a cognitive examination, should be completed, and components of a neurologic and physical examination may be indicated depending on the nature of the presenting problem.

Another important objective of the psychiatric evaluation is to gain an understanding of the patient’s experience of his or her illness. In many cases, this becomes the central focus for both the psychiatric assessment and interventions. It is often helpful to develop an understanding of the patient’s developmental and personal history as well as key dynamic conflicts, which in turn may help to make the patient’s experience with illness more comprehensible. Such an evaluation can include use of the concepts of stress, personality traits, coping strategies, and defense mechanisms. Observations and hypotheses that are developed can help to guide a patient’s psychotherapy aimed at diminishing distress and may also be helpful for the primary medical team in their interactions with the patient.

Finally, a full report synthesizing the information should be completed and include specific recommendations for additional evaluations and intervention. Ideally, the report should be accompanied by a discussion with the referring physician.

TREATMENTS USED IN PSYCHOSOMATIC MEDICINE

A host of interventions have been successfully utilized in psychosomatic medicine. Specific consideration must be given to medical illness and treatments when making recommendations for psychotropic medications. Psychotherapy also plays an important role in psychosomatic medicine and may vary in its structure and outcomes as compared with therapy that occurs in a mental health practice.

Psychopharmacologic recommendations need to consider several important factors. In addition to targeting a patient’s active symptoms, considering the history of illness and treatments, and weighing the particular side-effect profile of a particular medication, there are several other factors that must be considered that relate to the patient’s medical illness and treatment. It is critical to evaluate potential drug–drug interactions and contraindications to the use of potential psychotropic agents. Because the majority of psychotropic medications used are metabolized in the liver, awareness of liver function is important. General appreciation of side effects, such as weight gain, risk of development of diabetes, and cardiovascular risk, must be considered in the choice of medications. In addition, it is also important to incorporate knowledge of recent data that outline effectiveness and specific risks involved for patients with co-occurring psychiatric and physical disorders. For example, a greater understanding of the side effects of antipsychotic medications has raised concerns about the use of these medications in patients with dementia.

The use of psychosocial interventions also requires adaptation when used in this population. The methods and the goals of psychosocial interventions used in the medically ill are often determined by the consideration of disease onset, etiology, course, prognosis, treatment, and understanding of the nature of the presenting psychiatric symptoms in addition to an understanding of the patient’s existing coping skills and social support networks. However, there are ample data that psychosocial interventions are effective in addressing a series of identified problems and that such interventions in many cases are associated with a variety of positive clinical outcomes.

REFERENCES

Ader R, ed. Psychoneuroimmunology. 4th ed. New York: Elsevier; 2007.

Alexander F. Psychosomatic Medicine: Its Principles and Application. New York: Norton; 1950.

Cannon WB. The Wisdom of the Body. New York: Norton; 1932.

Chaturvedi SK, Desai G. Measurement and assessment of somatic symptoms. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2013;25(1):31–40.

Escobar J. Somatoform disorders. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, eds. Kaplan & Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9th ed. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Lippincott William & Wilkins; 2009:1927.

Fava GA, Sonino N. The clinical domains of psychosomatic medicine. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:849–858.

Goodwin RD, Olfson M, Shea S, Lantigua RA, Carrasquilo O, Gameroff MJ, Weissman MM. Asthma and mental disorders in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;25:479–483.

Hamilton JC, Eger M, Razzak S, Feldman MD, Hallmark N, Cheek S. Somatoform, factitious, and related diagnoses in the National Hospital Discharge Survey: Addressing the proposed DSM-5 revision. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(2):142–148.

Kaplan HI. History of psychosomatic medicine. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, eds: Kaplan and Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:2105.

Lesperance F, Frasure-Smith N, Theroux P, Irwin M. The association between major depression and levels of soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1, interleukin-6, and C-reactive protein in patients with recent acute coronary syndromes. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:271–277.

Lipsitt DR. Consultation-liaison psychiatry and psychosomatic medicine: The company they keep. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:896.

Matthews KA, Gump BB, Harris KF, Haney TL, Barefoot JC. Hostile behaviors predict cardiovascular mortality among men enrolled in the multiple risk factor intervention trial. Circulation. 2004;109:66–70.

Palta P, Samuel LJ, Miller ER, Szanton SL. Depression and oxidative stress: Results from a meta-analysis of observational studies. Psychosom Med. 2014;76(1):12–19.

Schrag AE, Mehta AR, Bhatia KP, Brown RJ, Frackowiak RS, Trimble MR, Ward NS, Rowe JB. The functional neuroimaging correlates of psychogenic versus organic dystonia. Brain. 2013;136(3):770–781.

Shorter E. From Paralysis to Fatigue: A History of Psychosomatic Illness in the Modern Era. New York: Free Press; 1992.

13.2 Somatic Symptom Disorder

13.2 Somatic Symptom Disorder

Somatic symptom disorder, also known as hypochondriasis, is characterized by 6 or more months of a general and nondelusional preoccupation with fears of having, or the idea that one has, a serious disease based on the person’s misinterpretation of bodily symptoms. This preoccupation causes significant distress and impairment in one’s life; it is not accounted for by another psychiatric or medical disorder; and a subset of individuals with somatic symptom disorder has poor insight about the presence of this disorder.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

In general medical clinic populations, the reported 6-month prevalence of this disorder is 4 to 6 percent, but it may be as high as 15 percent. Men and women are equally affected by this disorder. Although the onset of symptoms can occur at any age, the disorder most commonly appears in persons 20 to 30 years of age. Some evidence indicates that this diagnosis is more common among blacks than among whites, but social position, education level, gender, and marital status do not appear to affect the diagnosis. This disorder’s complaints reportedly occur in about 3 percent of medical students, usually in the first 2 years, but they are generally transient.

ETIOLOGY

Persons with this disorder augment and amplify their somatic sensations; they have low thresholds for, and low tolerance of, physical discomfort. For example, what persons normally perceive as abdominal pressure, persons with somatic symptom disorder experience as abdominal pain. They may focus on bodily sensations, misinterpret them, and become alarmed by them because of a faulty cognitive scheme.

Somatic symptom disorder can also be understood in terms of a social learning model. The symptoms of this disorder are viewed as a request for admission to the sick role made by a person facing seemingly insurmountable and insolvable problems. The sick role offers an escape that allows a patient to avoid noxious obligations, to postpone unwelcome challenges, and to be excused from usual duties and obligations.

Somatic symptom disorder is sometimes a variant form of other mental disorders, among which depressive disorders and anxiety disorders are most frequently included. An estimated 80 percent of patients with this disorder may have coexisting depressive or anxiety disorders. Patients who meet the diagnostic criteria for somatic symptom disorder may be somatizing subtypes of these other disorders.

The psychodynamic school of thought holds that aggressive and hostile wishes toward others are transferred (through repression and displacement) into physical complaints. The anger of patients with this disorder originates in past disappointments, rejections, and losses, but the patients express their anger in the present by soliciting the help and concern of other persons and then rejecting them as ineffective.

This disorder is also viewed as a defense against guilt, a sense of innate badness, an expression of low self-esteem, and a sign of excessive self-concern. Pain and somatic suffering thus become means of atonement and expiation (undoing) and can be experienced as deserved punishment for past wrongdoing (either real or imaginary) and for a person’s sense of wickedness and sinfulness.

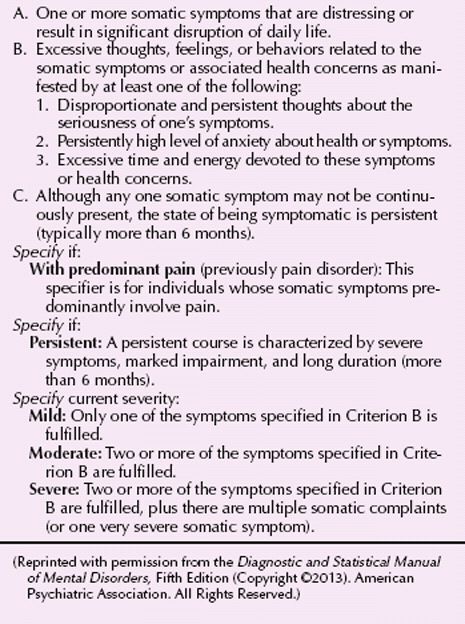

DIAGNOSIS

According to the fifth edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), the diagnostic criteria for somatic symptom disorder require that patients be preoccupied with the false belief that they have a serious disease, based on their misinterpretation of physical signs or sensations (Table 13.2-1). The belief must last at least 6 months, despite the absence of pathological findings on medical and neurological examinations. The diagnostic criteria also require that the belief cannot have the intensity of a delusion (more appropriately diagnosed as delusional disorder) and cannot be restricted to distress about appearance (more appropriately diagnosed as body dysmorphic disorder). The symptoms of somatic symptom disorder must be sufficiently intense to cause emotional distress or impair the patient’s ability to function in important areas of life. Clinicians may specify the presence of poor insight; patients do not consistently recognize that their concerns about disease are excessive.

Table 13.2-1

Table 13.2-1

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Somatic Symptom Disorder

CLINICAL FEATURES

Patients with somatic symptom disorder believe that they have a serious disease that has not yet been detected and they cannot be persuaded to the contrary. They may maintain a belief that they have a particular disease or, as time progresses, they may transfer their belief to another disease. Their convictions persist despite negative laboratory results, the benign course of the alleged disease over time, and appropriate reassurances from physicians. Yet, their beliefs are not sufficiently fixed to be delusions. Somatic symptom disorder is often accompanied by symptoms of depression and anxiety and commonly coexists with a depressive or anxiety disorder.

A severe case of somatic symptom disorder that highlights diagnostic, prognostic, and management issues is described in the case study.

Mr. K, a white man in his mid-30s, consulted a general medicine clinic complaining of gastrointestinal problems. Major presenting symptoms were a long list of physical symptoms and concerns mostly related to the gastrointestinal system. These included abdominal pain, left lower quadrant cramps, bloating, persistent sense of fullness in stomach hours after eating, intolerance to foods, constipation, decrease in physical stamina, heart palpitations, and feelings that “skin is getting yellow” and “not getting enough oxygen.” A review of systems disclosed disturbances from virtually every organ system, including tired eyes with blurred vision, sore throat and “lump” in throat, heart palpitations, irregular heartbeat, dizziness, trouble breathing, and general weakness.

The patient reported that symptoms started prior to the age of 30 years. For more than a decade, he had been seen by psychiatrists, general practitioners, and all kinds of medical specialists, including surgeons. He used the Internet constantly and traveled extensively in search of expert evaluations, seeking new procedures and diagnostic assessments. He had undergone repeated colonoscopies, sigmoidoscopies, and computed tomographic (CT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies, and ultrasound examinations of the abdomen that had failed to disclose any pathology. He was on disability and had been unable to work for more than 2 years due to his condition.

About 3 years before his visit to the medicine clinic, his abdominal complaints and his fixed belief that he had an intestinal obstruction led to an exploratory surgical intervention for the first time, apparently with negative findings. However, according to the patient, the surgery “got things even worse,” and since then he had been operated on at least five other occasions. During these surgeries he has undergone subtotal colectomies and ileostomies due to possible “adhesions” to rule out “mechanical” obstruction. However, available records from some of the surgeries do not disclose any specific pathology other than “intractable constipation.” Pathological specimens were also inconclusive.

The physical examination showed a well-developed, well-nourished male, who was afebrile. A complete physical and neurological examination was normal except for examination of the abdomen, which revealed multiple abdominal scars. Right ileostomy was present, with soft stool in the bag and active bowel sounds. There was no point tenderness and no abdominal distension. During the examination, the patient kept pointing to an area of “hardness” in the left lower quadrant that he thought was a “tight muscle strangling his bowels.” However, the examination did not disclose any palpable mass. Skin and extremities were all within normal limits, and all joints had full range of motion and no swelling. Musculature was well developed. Neurological examination was within normal limits. The patient was scheduled for brief monthly visits by the primary care physician, during which the doctor performed brief physicals, reassured the patient, and allowed the patient to talk about “stressors.” The physician avoided invasive tests or diagnostic procedures, did not prescribe any medications, and avoided telling the patient that the symptoms were mental or “all in his head.” The primary care physician then referred the patient back to psychiatry.

The psychiatrist confirmed a long list of physical symptoms that started before the age of 30 years, most of which remained medically unexplained. The psychiatric examination revealed some anxiety symptoms, including apprehension, tension, uneasiness, and somatic components such as blushing and palpitations that seemed particularly prominent in front of social situations. Possible symptoms of depression included mild dysphoria, low energy, and sleep disturbance, all of which the patient blamed on his “medical” problems. The mental status examination showed that Mr. K’s mood was rather somber and pessimistic, although he denied feeling sad or depressed. Affect was irritable. He was somatically focused and had little if any psychological insight. The examination revealed the presence of a few life stressors (unemployment, financial problems, and family issues) that the patient quickly discounted as unimportant. Although the patient continued to deny having any psychiatric problems or any need for psychiatric intervention or treatment, he agreed to a few regular visits to continue to assess his situation. He refused to engage anyone from his family in this process. Efforts to engage the patient with formal therapy such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) or a medication trial were all futile, so he was seen only for “supportive psychotherapy,” with the hope of developing rapport and preventing additional iatrogenic complications.

During the follow-up period, the patient was operated on at least one more time and continued to complain of abdominal bloating and constipation and to rely on laxatives. The belief that there was a mechanical obstruction of the intestines continued to be firmly held by the patient and bordered on the delusional. However, he continued to refuse pharmacological treatment. The only medication he accepted was a low-dose benzodiazepine for anxiety. He continued to monitor his intestinal function 24 hours per day and to seek evaluation by prominent specialists, traveling to high-profile specialty centers far from home in search of solutions. (Courtesy of J. I. Escobar, M.D.)

Although DSM-5 specifies that the symptoms must be present for at least 6 months, transient manifestations can occur after major stresses, most commonly the death or serious illness of someone important to the patient or a serious (perhaps life-threatening) illness that has been resolved but that leaves the patient temporarily affected in its wake. Such states that last fewer than 6 months are diagnosed as “Other Specified Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders” in DSM-5. Transient somatic symptom disorder responses to external stress generally remit when the stress is resolved, but they can become chronic if reinforced by persons in the patient’s social system or by health professionals.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Somatic symptom disorder must be differentiated from nonpsychiatric medical conditions, especially disorders that show symptoms that are not necessarily easily diagnosed. Such diseases include acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), endocrinopathies, myasthenia gravis, multiple sclerosis, degenerative diseases of the nervous system, systemic lupus erythematosus, and occult neoplastic disorders.

Somatic symptom disorder is differentiated from illness anxiety disorder (a new diagnosis in DSM-5 discussed in Section 13.3) by the emphasis in illness anxiety disorder on fear of having a disease rather than a concern about many symptoms. Patients with illness anxiety disorder usually complain about fewer symptoms than patients with somatic symptom disorder; they are primarily concerned about being sick.

Conversion disorder is acute and generally transient and usually involves a symptom rather than a particular disease. The presence or absence of la belle indifférence is an unreliable feature with which to differentiate the two conditions. Patients with body dysmorphic disorder wish to appear normal, but believe that others notice that they are not, whereas those with somatic symptom disorder seek out attention for their presumed diseases.

Somatic symptom disorder can also occur in patients with depressive disorders and anxiety disorders. Patients with panic disorder may initially complain that they are affected by a disease (e.g., heart trouble), but careful questioning during the medical history usually uncovers the classic symptoms of a panic attack. Delusional disorder beliefs occur in schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, but can be differentiated from somatic symptom disorder by their delusional intensity and by the presence of other psychotic symptoms. In addition, schizophrenic patients’ somatic delusions tend to be bizarre, idiosyncratic, and out of keeping with their cultural milieus, as illustrated in the case below.

A 52-year-old man complained “my guts are rotting away.” Even after an extensive medical workup, he could not be reassured that he was not ill.

Somatic symptom disorder is distinguished from factitious disorder with physical symptoms and from malingering in that patients with somatic symptom disorder actually experience and do not simulate the symptoms they report.

COURSE AND PROGNOSIS

The course of the disorder is usually episodic; the episodes last from months to years and are separated by equally long quiescent periods. There may be an obvious association between exacerbations of somatic symptoms and psychosocial stressors. Although no well-conducted large outcome studies have been reported, an estimated one third to one half of all patients with somatic symptom disorder eventually improve significantly. A good prognosis is associated with high socioeconomic status, treatment-responsive anxiety or depression, sudden onset of symptoms, the absence of a personality disorder, and the absence of a related nonpsychiatric medical condition. Most children with the disorder recover by late adolescence or early adulthood.

TREATMENT

Patients with somatic symptom disorder usually resist psychiatric treatment, although some accept this treatment if it takes place in a medical setting and focuses on stress reduction and education in coping with chronic illness. Group psychotherapy often benefits such patients, in part because it provides the social support and social interaction that seem to reduce their anxiety. Other forms of psychotherapy, such as individual insight-oriented psychotherapy, behavior therapy, cognitive therapy, and hypnosis, may be useful.

Frequent, regularly scheduled physical examinations help to reassure patients that their physicians are not abandoning them and that their complaints are being taken seriously. Invasive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures should only be undertaken, however, when objective evidence calls for them. When possible, the clinician should refrain from treating equivocal or incidental physical examination findings.

Pharmacotherapy alleviates somatic symptom disorder only when a patient has an underlying drug-responsive condition, such as an anxiety disorder or depressive disorder. When somatic symptom disorder is secondary to another primary mental disorder, that disorder must be treated in its own right. When the disorder is a transient situational reaction, clinicians must help patients cope with the stress without reinforcing their illness behavior and their use of the sick role as a solution to their problems.

OTHER SPECIFIED OR UNSPECIFIED SOMATIC SYMPTOM DISORDER

This DSM-5 category is used to describe conditions characterized by one or more unexplained physical symptoms of at least 6 months’ duration, which are below the threshold for a diagnosis of somatic symptom disorder. The symptoms are not caused, or fully explained, by another medical, psychiatric, or substance abuse disorder, and they cause clinical significant distress or impairment.

Two types of symptom patterns may be seen in patients with other specified or unspecified somatic symptom disorder: those involving the autonomic nervous system and those involving sensations of fatigue or weakness. In what is sometimes referred to as autonomic arousal disorder, some patients are affected with symptoms that are limited to bodily functions innervated by the autonomic nervous system. Such patients have complaints involving the cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, urogenital, and dermatological systems. Other patients complain of mental and physical fatigue, physical weakness and exhaustion, and inability to perform many everyday activities because of their symptoms. Some clinicians believe this syndrome is neurasthenia, a diagnosis used primarily in Europe and Asia. The syndrome may overlap with chronic fatigue syndrome, which various research reports have hypothesized to involved psychiatric, virological, and immunological factors. (See Chapter 14, which discusses chronic fatigue syndrome in depth.) Other conditions included in this unspecified category of somatic symptom disorder are pseudocyesis (discussed in Chapter 27) and conditions that may not have met the 6-month criterion of the other somatic symptom disorders.

REFERENCES

Dimsdale JE, Creed F, Escobar J, Sharpe M, Wulsin L, Barsky A, Lee S, Irwin MR, Levenson J. Somatic symptom disorder: An important change in DSM. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75(3):223–228.

Frances A. The new somatic symptom disorder in DSM-5 risks mislabeling many people as mentally ill. BMJ. 2013;346:f1580.

Halder SL, Locke GR 3rd, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd. Impact of functional gastrointestinal disorders on health-related quality of life: A population-based case-control study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:233.

Karvonen JT, Veijola J, Jokelainen J, Laksy K, Jarvelin M-R, Joukamaa M. Somatization disorder in the young adult population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26:9–12.

Keefe FJ, Abernethy AP, Campbell LC. Psychological approaches to understanding and treating disease-related pain. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:601–630.

Matthews SC, Camacho A, Mills PJ, Dimsdale JE. The internet for medical information about cancer: Help or hindrance? Psychosomatics. 2003;44:100–103.

Prior KN, Bond MJ. Somatic symptom disorders and illness behaviour: Current perspectives. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2013;25(1):5–18.

Rief W, Martin A. How to use the new DSM-5 somatic symptom disorder diagnosis in research and practice: a critical evaluation and a proposal for modifications. Annu Rev Clin Psychol . 2014;10:339–67.

Sirri L, Fava GA. Diagnostic criteria for psychosomatic research and somatic symptom disorders. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2013;25(1):19–30.

Smith TW. Hostility and health: Current status of psychosomatic hypothesis. In: Salovey P, Rothman AJ, eds. Social Psychology of Health. New York: Psychology Press; 2003:325–341.

Somashekar B, Jainer A, Wuntakal B. Psychopharmacotherapy of somatic symptoms disorders. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2013;25(1):107–115.

Tomenson B, Essau C, Jacobi F, Ladwig KH, Leiknes KA, Lieb R, Meinlschmidt G, McBeth J, Rosmalen J, Rief W, Sumathipala A, Creed F, EURASMUS Population Based Study Group. Total somatic symptom score as a predictor of health outcome in somatic symptom disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;203(5):373–380.

13.3 Illness Anxiety Disorder

13.3 Illness Anxiety Disorder

Illness anxiety disorder is a new diagnosis in the fifth edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) that applies to those persons who are preoccupied with being sick or with developing a disease of some kind. It is a variant of somatic symptom disorder (hypochondriasis) described in Section 13.2. As stated in DSM-5: Most individuals with hypochondriasis are now classified as having somatic symptom disorder; however, in a minority of cases, the diagnosis of illness anxiety disorder applies instead. In describing the differential diagnosis between the two, according to DSM-5, somatic symptom disorder is diagnosed when somatic symptoms are present, whereas in illness anxiety disorder, there are few or no somatic symptoms and persons are “primarily concerned with the idea they are ill.” The diagnosis may also be used for persons who do, in fact, have a medical illness but whose anxiety is out of proportion to their diagnosis and who assume the worst possible outcome imaginable.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The prevalence of this disorder is unknown aside from using data that relate to hypochondriasis, which gives a prevalence of 4 to 6 percent in a general medical clinic population. In other surveys, up to 15 percent of persons in the general population worry about becoming sick and incapacitated as a result. One might expect the disorder to be diagnosed more frequently in older rather than younger persons. There is no evidence to date that the diagnosis is more common among different races or that gender, social position, education level, and marital status affect the diagnosis.

ETIOLOGY

The etiology is unknown. The social learning model described for somatic symptom disorder may apply to this disorder as well. In that construct, the fear of illness is viewed as a request to play the sick role made by someone facing seemingly insurmountable and insolvable problems. The sick role offers an escape that allows a patient to be excused from usual duties and obligations.

The psychodynamic school of thought is also similar to somatic symptom disorder. Aggressive and hostile wishes toward others are transferred into minor physical complaints or the fear of physical illness. The anger of patients with illness anxiety disorder, as in those with hypochondriasis, originates in past disappointments, rejections, and losses. Similarly, the fear of illness is also viewed as a defense against guilt, a sense of innate badness, an expression of low self-esteem, and a sign of excessive self-concern. The feared illness may also be seen as punishment for past either real or imaginary wrongdoing. The nature of the person’s relationships to significant others in his or her past life may also be significant. A parent who died from a specific illness, for example, might be the stimulus for the fear of developing that illness in the offspring of that parent. The type of the fear may also be symbolic of unconscious conflicts that are reflected in the type of illness of which the person is afraid or the organ system selected (e.g., heart, kidney).

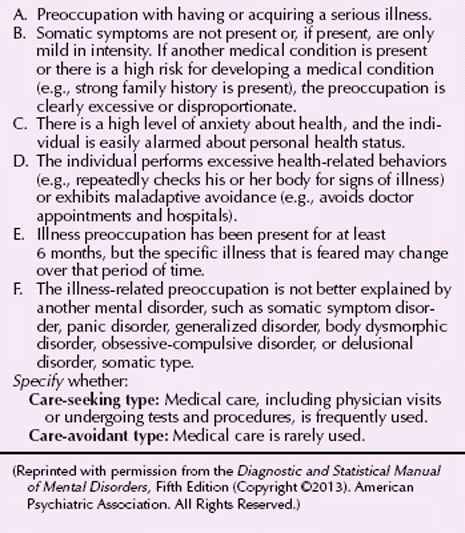

DIAGNOSIS

The major DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for illness anxiety disorder are that patients be preoccupied with the false belief that they have or will develop a serious disease and there are few if any physical signs or symptoms (Table 13.3-1). The belief must last at least 6 months, and there are no pathological findings on medical or neurological examinations. The belief cannot have the fixity of a delusion (more appropriately diagnosed as delusional disorder) and cannot be distress about appearance (more appropriately diagnosed as body dysmorphic disorder). The anxiety about illness must be incapacitating and cause emotional distress or impair the patient’s ability to function in important areas of life. Some persons with the disorder may visit physicians (care-seeking type) while others may not (care-avoidant type). The majority of patients, however, make repeated visits to physicians and other health care providers.

Table 13.3-1

Table 13.3-1

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Illness Anxiety Disorder

CLINICAL FEATURES

Patients with illness anxiety disorder, like those with somatic symptom disorder, believe that they have a serious disease that has not yet been diagnosed, and they cannot be persuaded to the contrary. They may maintain a belief that they have a particular disease or, as time progresses, they may transfer their belief to another disease. Their convictions persist despite negative laboratory results, the benign course of the alleged disease over time, and appropriate reassurances from physicians. Their preoccupation with illness interferes with their interaction with family, friends, and coworkers. They are often addicted to Internet searches about their feared illness, inferring the worst from information (or misinformation) they find there.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Illness anxiety disorder must be differentiated from other medical conditions. Too often these patients are dismissed as “chronic complainers” and careful medical examinations are not performed. Patients with illness anxiety disorder are differentiated from those with somatic symptom disorder by the emphasis in illness anxiety disorder on fear of having a disease versus the emphasis in somatic symptom disorder on concern about many symptoms; but both may exist to varying degrees in each disorder. Patients with illness anxiety disorder usually complain about fewer symptoms than patients with somatic symptom disorder. Somatic symptom disorder usually has an onset before age 30, whereas illness anxiety disorder has a less specific age of onset. Conversion disorder is acute, generally transient, and usually involves a symptom rather than a particular disease. Pain disorder is chronic, as is hypochondriasis, but the symptoms are limited to complaints of pain. The fear of illness can also occur in patients with depressive and anxiety disorders. If a patient meets the full diagnostic criteria for both illness anxiety disorder and another major mental disorder, such as major depressive disorder or generalized anxiety disorder, the patient should receive both diagnoses. Patients with panic disorder may initially complain that they are affected by a disease (e.g., heart trouble), but careful questioning during the medical history usually uncovers the classic symptoms of a panic attack. Delusional beliefs occur in schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders but can be differentiated from illness anxiety disorder by their delusional intensity and by the presence of other psychotic symptoms. In addition, schizophrenic patients’ somatic delusions tend to be bizarre, idiosyncratic, and out of keeping with their cultural milieus.

Illness anxiety disorder can be differentiated from obsessive-compulsive disorder by the singularity of their beliefs and by the absence of compulsive behavioral traits; but there is often an obsessive quality to the patients fear.

COURSE AND PROGNOSIS

Because the disorder is only recently described, there are no reliable data about the prognosis. One may extrapolate from the course of somatic symptom disorder, which is usually episodic; the episodes last from months to years and are separated by equally long quiescent periods. As with hypochondriasis, a good prognosis is associated with high socioeconomic status, treatment-responsive anxiety or depression, sudden onset of symptoms, the absence of a personality disorder, and the absence of a related nonpsychiatric medical condition.

TREATMENT

As with somatic symptom disorder, patients with illness anxiety disorder usually resist psychiatric treatment, although some accept this treatment if it takes place in a medical setting and focuses on stress reduction and education in coping with chronic illness. Group psychotherapy may be of help especially if the group is homogeneous with patients suffering from the same disorder. Other forms of psychotherapy, such as individual insight-oriented psychotherapy, behavior therapy, cognitive therapy, and hypnosis, may be useful.

The role of frequent, regularly scheduled physical examinations is controversial. Some patients may benefit from being reassured that their complaints are being taken seriously and that they do not have the illness of which they are afraid. Others, however, are resistant to seeing a doctor in the first place, or, if having done so, of accepting the fact that there is nothing to worry about. Invasive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures should only be undertaken when objective evidence calls for them. When possible, the clinician should refrain from treating equivocal or incidental physical examination findings.

Pharmacotherapy may be of help in alleviating the anxiety generated by the fear that the patient has about illness, especially if it is one that is life-threatening; but it is only ameliorative and cannot provide lasting relief. That can only come from an effective psychotherapeutic program that is acceptable to the patient and in which he or she is willing and able to participate.

REFERENCES

Blumenfield M, Strain JJ. Psychosomatic Medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

Brakoulias V. DSM-5 bids farewell to hypochondriasis and welcomes somatic symptom disorder and illness anxiety disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014 Feb 26. [Epub ahead of print].

Brody S. Hypochondriasis: Attentional, sensory, and cognitive factors. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(1):98.

El-Gabalawy R, Mackenzie CS, Thibodeau MA, Asmundson GJG, Sareen J. Health anxiety disorders in older adults: Conceptualizing complex conditions in late life. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(8):1096–1105.

Escobar JI, Gara MA, Diaz-Martinez A, Interian A, Warman M. Effectiveness of a time-limited, cognitive behavior therapy–type intervention among primary care patients with medically unexplained symptoms. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:328–335.

Gropalis M, Bleichhardt G, Hiller W, Witthoft M. Specificity and modifiability of cognitive biases in hypochondriasis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81(3):558–565.

Hirsch JK, Walker KL, Chang EC, Lyness JM. Illness burden and symptoms of anxiety in older adults: Optimism and pessimism as moderators. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(10):1614–1621.

Höfling V, Weck F. Assessing bodily preoccupations is sufficient: Clinically effective screening for hypochondriasis. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75(6):526–531.

Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The social readjustment rating scale. J Psychosom Res. 1967;11:213–218.

Kroenke K, Sharpe M, Sykes R. Revising the classification of somatoform disorders: Key questions and preliminary recommendations. Psychosomatics. 2007;48:277–285.

Lee S, Lam IM, Kwok KP, Leung C. A community-based epidemiological study of health anxiety and generalized anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28(2):187–194.

Muschalla B, Glatz J, Linden M. Heart-related anxieties in relation to general anxiety and severity of illness in cardiology patients. Psychol Health Med. 2014;19(1):83–92.

Noyes R Jr, Stuart SP, Langbehn DR, Happel RL, Longley SL, Muller BA, Yagla SJ. Test of an interpersonal model of hypochondriasis. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:292–300.

Starcevic V. Hypochondriasis and health anxiety: conceptual challenges. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(1):7–8.

Voigt K, Wollburg E, Weinmann N, Herzog A, Meyer B, Langs G, Löwe B. Predictive validity and clinical utility of DSM-5 Somatic Symptom Disorder: Prospective 1-year follow-up study. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75(4):358–361.

13.4 Functional Neurological Symptom Disorder (Conversion Disorder)

13.4 Functional Neurological Symptom Disorder (Conversion Disorder)

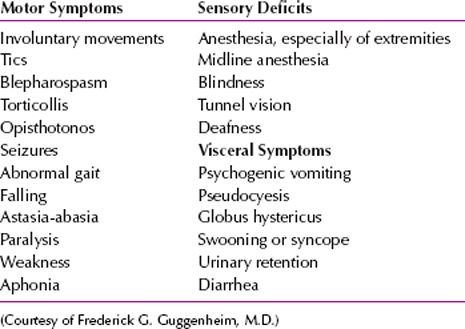

Conversion disorder, also called functional neurological symptom disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5), is an illness of symptoms or deficits that affect voluntary motor or sensory functions, which suggest another medical condition, but that is judged to be caused by psychological factors because the illness is preceded by conflicts or other stressors. The symptoms or deficits of conversion disorder are not intentionally produced, are not caused by substance use, are not limited to pain or sexual symptoms, and the gain is primarily psychological and not social, monetary, or legal (Table 13.4-1).

Table 13.4-1

Table 13.4-1

Common Symptoms of Conversion Disorder

The syndrome currently known as conversion disorder was originally combined with the syndrome known as somatization disorder and was referred to as hysteria, conversion reaction, or dissociative reaction. Paul Briquet and Jean-Martin Charcot contributed to the development of the concept of conversion disorder by noting the influence of heredity on the symptom and the common association with a traumatic event. The term conversion was introduced by Sigmund Freud, who, based on his work with Anna O, hypothesized that the symptoms of conversion disorder reflect unconscious conflicts.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Some symptoms of conversion disorder that are not sufficiently severe to warrant the diagnosis may occur in up to one third of the general population sometime during their lives. Reported rates of conversion disorder vary from 11 of 100,000 to 300 of 100,000 in general population samples. Among specific populations, the occurrence of conversion disorder may be even higher than that, perhaps making conversion disorder the most common somatoform disorder in some populations. Several studies have reported that 5 to 15 percent of psychiatric consultations in a general hospital and 25 to 30 percent of admissions to a Veterans Administration hospital involve patients with conversion disorder diagnoses.

The ratio of women to men among adult patients is at least 2 to 1 and as much as 10 to 1; among children, an even higher predominance is seen in girls. Symptoms are more common on the left than on the right side of the body in women. Women who present with conversion symptoms are more likely subsequently to develop somatization disorder than women who have not had conversion symptoms. An association exists between conversion disorder and antisocial personality disorder in men. Men with conversion disorder have often been involved in occupational or military accidents. The onset of conversion disorder is generally from late childhood to early adulthood and is rare before 10 years of age or after 35 years of age, but onset as late as the ninth decade of life has been reported. When symptoms suggest a conversion disorder onset in middle or old age, the probability of an occult neurological or other medical condition is high. Conversion symptoms in children younger than 10 years of age are usually limited to gait problems or seizures.

Data indicate that conversion disorder is most common among rural populations, persons with little education, those with low intelligence quotients, those in low socioeconomic groups, and military personnel who have been exposed to combat situations. Conversion disorder is commonly associated with comorbid diagnoses of major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, and schizophrenia and shows an increased frequency in relatives of probands with conversion disorder. Limited data suggest that conversion symptoms are more frequent in relatives of people with conversion disorder. An increased risk of conversion disorder in monozygotic, but not dizygotic, twin pairs has been reported.

COMORBIDITY

Medical and, especially, neurological disorders occur frequently among patients with conversion disorders. What is typically seen in these comorbid neurological or medical conditions is an elaboration of symptoms stemming from the original organic lesion.

Depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and somatization disorders are especially noted for their association with conversion disorder. Conversion disorder in schizophrenia is reported, but it is uncommon. Studies of patients admitted to a psychiatric hospital for conversion disorder reveal, on further study, that one quarter to one half have a clinically significant mood disorder or schizophrenia.

Personality disorders also frequently accompany conversion disorder, especially the histrionic type (in 5 to 21 percent of cases) and the passive-dependent type (9 to 40 percent of cases). Conversion disorders can occur, however, in persons with no predisposing medical, neurological, or psychiatric disorder.

ETIOLOGY

Psychoanalytic Factors

According to psychoanalytic theory, conversion disorder is caused by repression of unconscious intrapsychic conflict and conversion of anxiety into a physical symptom. The conflict is between an instinctual impulse (e.g., aggression or sexuality) and the prohibitions against its expression. The symptoms allow partial expression of the forbidden wish or urge but disguise it, so that patients can avoid consciously confronting their unacceptable impulses; that is, the conversion disorder symptom has a symbolic relation to the unconscious conflict—for example, vaginismus protects the patient from expressing unacceptable sexual wishes. Conversion disorder symptoms also allow patients to communicate that they need special consideration and special treatment. Such symptoms may function as a nonverbal means of controlling or manipulating others.

Learning Theory

In terms of conditioned learning theory, a conversion symptom can be seen as a piece of classically conditioned learned behavior; symptoms of illness, learned in childhood, are called forth as a means of coping with an otherwise impossible situation.

Biological Factors

Increasing data implicate biological and neuropsychological factors in the development of conversion disorder symptoms. Preliminary brain-imaging studies have found hypometabolism of the dominant hemisphere and hypermetabolism of the nondominant hemisphere and have implicated impaired hemispheric communication in the cause of conversion disorder. The symptoms may be caused by an excessive cortical arousal that sets off negative feedback loops between the cerebral cortex and the brainstem reticular formation. Elevated levels of corticofugal output, in turn, inhibit the patient’s awareness of bodily sensation, which may explain the observed sensory deficits in some patients with conversion disorder. Neuropsychological tests sometimes reveal subtle cerebral impairments in verbal communication, memory, vigilance, affective incongruity, and attention in these patients.

DIAGNOSIS

The DSM-5 limits the diagnosis of conversion disorder to those symptoms that affect a voluntary motor or sensory function, that is, neurological symptoms. Physicians cannot explain the neurological symptoms solely on the basis of any known neurological condition.

The diagnosis of conversion disorder requires that clinicians find a necessary and critical association between the cause of the neurological symptoms and psychological factors, although the symptoms cannot result from malingering or factitious disorder. The diagnosis of conversion disorder also excludes symptoms of pain and sexual dysfunction and symptoms that occur only in somatization disorder. DSM-5 allows specification of the type of symptom or deficit seen in conversion disorder, for example, with weakness or paralysis, with abnormal movements, or with attacks or seizures.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Paralysis, blindness, and mutism are the most common conversion disorder symptoms. Conversion disorder may be most commonly associated with passive-aggressive, dependent, antisocial, and histrionic personality disorders. Depressive and anxiety disorder symptoms often accompany the symptoms of conversion disorder, and affected patients are at risk for suicide.

Mr. J is a 28-year-old single man who is employed in a factory. He was brought to an emergency department by his father, complaining that he had lost his vision while sitting in the back seat on the way home from a family gathering. He had been playing volleyball at the gathering but had sustained no significant injury except for the volleyball hitting him in the head a few times. As was usual for this man, he had been reluctant to play volleyball because of the lack of his athletic skills and was placed on a team at the last moment. He recalls having some problems with seeing during the game, but his vision did not become ablated until he was in the car on the way home. By the time he got to the emergency department, his vision was improving, although he still complained of blurriness and mild diplopia. The double vision could be attenuated by having him focus on items at different distances.

On examination, Mr. J was fully cooperative, somewhat uncertain about why this would have occurred, and rather nonchalant. Pupillary, oculomotor, and general sensorimotor examinations were normal. After being cleared medically, the patient was sent to a mental health center for further evaluation.

At the mental health center, the patient recounts the same story as he did in the emergency department, and he was still accompanied by his father. He began to recount how his vision started to return to normal when his father pulled over on the side of the road and began to talk to him about the events of the day. He spoke with his father about how he had felt embarrassed and somewhat conflicted about playing volleyball and how he had felt that he really should play because of external pressures. Further history from the patient and his father revealed that this young man had been shy as an adolescent, particularly around athletic participation. He had never had another episode of visual loss. He did recount feeling anxious and sometimes not feeling well in his body during athletic activities.

Discussion with the patient at the mental health center focused on the potential role of psychological and social factors in acute vision loss. The patient was somewhat perplexed by this but was also amenable to discussion. He stated that he clearly recognized that he began seeing and feeling better when his father pulled off to the side of the road and discussed things with him. Doctors admitted that they did not know the cause of the vision loss and that it would likely not return. The patient and his father were satisfied with the medical and psychiatric evaluation and agreed to return for care if there were any further symptoms. The patient was appointed a follow-up time at the outpatient psychiatric clinic. (Courtesy of Michael A. Hollifield, M.D.)

Sensory Symptoms

In conversion disorder, anesthesia and paresthesia are common, especially of the extremities. All sensory modalities can be involved, and the distribution of the disturbance is usually inconsistent with either central or peripheral neurological disease. Thus, clinicians may see the characteristic stocking-and-glove anesthesia of the hands or feet or the hemianesthesia of the body beginning precisely along the midline.

Conversion disorder symptoms may involve the organs of special sense and can produce deafness, blindness, and tunnel vision. These symptoms can be unilateral or bilateral, but neurological evaluation reveals intact sensory pathways. In conversion disorder blindness, for example, patients walk around without collisions or self-injury, their pupils react to light, and their cortical-evoked potentials are normal.

Motor Symptoms

The motor symptoms of conversion disorder include abnormal movements, gait disturbance, weakness, and paralysis. Gross rhythmical tremors, choreiform movements, tics, and jerks may be present. The movements generally worsen when attention is called to them. One gait disturbance seen in conversion disorder is astasia-abasia, which is a wildly ataxic, staggering gait accompanied by gross, irregular, jerky truncal movements and thrashing and waving arm movements. Patients with the symptoms rarely fall; if they do, they are generally not injured.

Other common motor disturbances are paralysis and paresis involving one, two, or all four limbs, although the distribution of the involved muscles does not conform to the neural pathways. Reflexes remain normal; the patients have no fasciculations or muscle atrophy (except after long-standing conversion paralysis); electromyography findings are normal.

Seizure Symptoms

Pseudoseizures are another symptom in conversion disorder. Clinicians may find it difficult to differentiate a pseudoseizure from an actual seizure by clinical observation alone. Moreover, about one third of the patient’s pseudoseizures also have a coexisting epileptic disorder. Tongue-biting, urinary incontinence, and injuries after falling can occur in pseudoseizures, although these symptoms are generally not present. Pupillary and gag reflexes are retained after pseudoseizure, and patients have no postseizure increase in prolactin concentrations.

Other Associated Features

Several psychological symptoms have also been associated with conversion disorder.

Primary Gain. Patients achieve primary gain by keeping internal conflicts outside their awareness. Symptoms have symbolic value; they represent an unconscious psychological conflict.

Secondary Gain. Patients accrue tangible advantages and benefits as a result of being sick; for example, being excused from obligations and difficult life situations, receiving support and assistance that might not otherwise be forthcoming, and controlling other persons’ behavior.

La Belle Indifférence. La belle indifférence is a patient’s inappropriately cavalier attitude toward serious symptoms; that is, the patient seems to be unconcerned about what appears to be a major impairment. That bland indifference is also seen in some seriously ill medical patients who develop a stoic attitude. The presence or absence of la belle indifférence is not pathognomonic of conversion disorder, but it is often associated with the condition.

Identification. Patients with conversion disorder may unconsciously model their symptoms on those of someone important to them. For example, a parent or a person who has recently died may serve as a model for conversion disorder. During pathological grief reaction, bereaved persons commonly have symptoms of the deceased.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

One of the major problems in diagnosing conversion disorder is the difficulty of definitively ruling out a medical disorder. Concomitant nonpsychiatric medical disorders are common in hospitalized patients with conversion disorder, and evidence of a current or previous neurological disorder or a systemic disease affecting the brain has been reported in 18 to 64 percent of such patients. An estimated 25 to 50 percent of patients classified as having conversion disorder eventually receive diagnoses of neurological or nonpsychiatric medical disorders that could have caused their earlier symptoms. Thus, a thorough medical and neurological workup is essential in all cases. If the symptoms can be resolved by suggestion, hypnosis, or parenteral amobarbital (Amytal) or lorazepam (Ativan), they are probably the result of conversion disorder.

Neurological disorders (e.g., dementia and other degenerative diseases), brain tumors, and basal ganglia disease must be considered in the differential diagnosis. For example, weakness may be confused with myasthenia gravis, polymyositis, acquired myopathies, or multiple sclerosis. Optic neuritis may be misdiagnosed as conversion disorder blindness. Other diseases that can cause confusing symptoms are Guillain-Barré syndrome, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, periodic paralysis, and early neurological manifestations of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Conversion disorder symptoms occur in schizophrenia, depressive disorders, and anxiety disorders, but these other disorders are associated with their own distinct symptoms that eventually make differential diagnosis possible.

Sensorimotor symptoms also occur in somatization disorder. But somatization disorder is a chronic illness that begins early in life and includes symptoms in many other organ systems. In hypochondriasis, patients have no actual loss or distortion of function; the somatic complaints are chronic and are not limited to neurological symptoms, and the characteristic hypochondriacal attitudes and beliefs are present. If the patient’s symptoms are limited to pain, pain disorder can be diagnosed. Patients whose complaints are limited to sexual function are classified as having a sexual dysfunction, rather than conversion disorder.

In both malingering and factitious disorder, the symptoms are under conscious, voluntary control. A malingerer’s history is usually more inconsistent and contradictory than that of a patient with conversion disorder, and a malingerer’s fraudulent behavior is clearly goal directed.

Table 13.4-2 lists examples of important tests that are relevant to conversion disorder symptoms.

Table 13.4-2

Table 13.4-2

Distinctive Physical Examination Findings in Conversion Disorder

COURSE AND PROGNOSIS

The onset of conversion disorder is usually acute, but a crescendo of symptomatology may also occur. Symptoms or deficits are usually of short duration, and approximately 95 percent of acute cases remit spontaneously, usually within 2 weeks in hospitalized patients. If symptoms have been present for 6 months or longer, the prognosis for symptom resolution is less than 50 percent and diminishes further the longer that conversion is present. Recurrence occurs in one fifth to one fourth of people within 1 year of the first episode. Thus, one episode is a predictor for future episodes. A good prognosis is heralded by acute onset, presence of clearly identifiable stressors at the time of onset, a short interval between onset and the institution of treatment, and above average intelligence. Paralysis, aphonia, and blindness are associated with a good prognosis, whereas tremor and seizures are poor prognostic factors.

TREATMENT

Resolution of the conversion disorder symptom is usually spontaneous, although it is probably facilitated by insight-oriented supportive or behavior therapy. The most important feature of the therapy is a relationship with a caring and confident therapist. With patients who are resistant to the idea of psychotherapy, physicians can suggest that the psychotherapy will focus on issues of stress and coping. Telling such patients that their symptoms are imaginary often makes them worse. Hypnosis, anxiolytics, and behavioral relaxation exercises are effective in some cases. Parenteral amobarbital or lorazepam may be helpful in obtaining additional historic information, especially when a patient has recently experienced a traumatic event. Psychodynamic approaches include psychoanalysis and insight-oriented psychotherapy, in which patients explore intrapsychic conflicts and the symbolism of the conversion disorder symptoms. Brief and direct forms of short-term psychotherapy have also been used to treat conversion disorder. The longer the duration of these patients’ sick role and the more they have regressed, the more difficult the treatment.

REFERENCES

Ani C, Reading R, Lynn R, Forlee S, Garralda E. Incidence and 12-month outcome of non-transient childhood conversion disorder in the UK and Ireland. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(6):413–418.

Bryant RA, Das P. The neural circuitry of conversion disorder and its recovery. J Abnorm Psychology. 2012;121(1):289.

Carson AJ, Brown R, David AS, Duncan R, Edwards MJ, Goldstein LH, Grunewald R, Howlett S, Kanaan R, Mellers J, Nicholson TR, Reuber M, Schrag AE, Stone J, Voon V; UK-FNS. Functional (conversion) neurological symptoms: Research since the millennium. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(8):842–850.

Daum C, Aybek S. Validity of the “drift without pronation” sign in conversion disorder. BMC Neurol. 2013;13:31.

Edwards MJ, Stone J, Nielsen G. Physiotherapists and patients with functional (psychogenic) motor symptoms: A survey of attitudes and interest. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(6):655–658.

Guz H, Doganay Z, Ozkan A, Colak E, Tomac A, Sarisoy G. Conversion and somatization disorders: Dissociative symptoms and other characteristics. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:287–291.

Krasnik C, Grant C. Conversion disorder: Not a malingering matter. Paediatr Child Health. 2012;17(5):246.

Martinez MS, Fristad MA. Conversion from bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (BP-NOS) to bipolar I or II in youth with family history as a predictor of conversion. J Affect Disord. 2013;148(2–3):431–434.

McCormack R, Moriarty J, Mellers JD, Shotbolt P, Pastena R, Landes N, Goldstein L, Fleminger S, David AS. Specialist inpatient treatment for severe motor conversion disorder: a retrospective comparative study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013.

Nicholson TR, Aybek S, Kempton MJ, Daly EM, Murphy DG, David AS, Kanaan RA. A structural MRI study of motor conversion disorder: evidence of reduction in thalamic volume. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(2):227–229.

Stone J, Smyth R, Carson A, Lewis S, Prescott R, Warlow C, Sharpe M. Systematic review of misdiagnosis of conversion symptoms and “hysteria.” BMJ. 2005;331(7523):989.

Tezcan E, Atmaca M, Kuloglu M, Gecici O, Buyukbayram A, Tutkun H. Dissociative disorders in Turkish inpatients with conversion disorder. Comp Psychiatry. 2003;44:324.

13.5 Psychological Factors Affecting Other Medical Conditions

13.5 Psychological Factors Affecting Other Medical Conditions

Psychosomatic medicine has been a specific area of study within the field of psychiatry. It is based on two basic assumptions: There is a unity of mind and body; and psychological factors must be taken into account when considering all disease states.

Concepts derived from the field of psychosomatic medicine influenced both the emergence of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), which relies heavily on examining psychological factors in the maintenance of health, and the field of holistic medicine, with its emphasis on examining and treating the whole patient, not just his or her illness. The concepts of psychosomatic medicine also influenced the field of behavioral medicine, which integrates the behavioral sciences and the biomedical approach to the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of disease. Psychosomatic concepts have contributed greatly to those approaches to medical care.

The concepts of psychosomatic medicine are subsumed in the diagnostic entity of “Psychological Factors Affecting Other Medical Conditions.” This category covers physical disorders caused by or adversely affected by emotional or psychological factors. A medical condition must always be present for the diagnosis to be made.

CLASSIFICATION

The diagnostic criteria for “Psychological Factors Affecting Other Medical Conditions” excluded (1) classic mental disorders that have physical symptoms as part of the disorder (e.g., conversion disorder, in which a physical symptom is produced by psychological conflict); (2) somatization disorder, in which the physical symptoms are not based on organic pathology; (3) hypochondriasis, in which patients have an exaggerated concern with their health; (4) physical complaints that are frequently associated with mental disorders (e.g., dysthymic disorder, which usually has such somatic accompaniments as muscle weakness, asthenia, fatigue, and exhaustion); and (5) physical complaints associated with substance-related disorders (e.g., coughing associated with nicotine dependence).

STRESS THEORY

Stress can be described as a circumstance that disturbs, or is likely to disturb, the normal physiological or psychological functioning of a person. In the 1920s, Walter Cannon (1871–1945) conducted the first systematic study of the relation of stress to disease. He demonstrated that stimulation of the autonomic nervous system, particularly the sympathetic system, readied the organism for the “fight-or-flight” response characterized by hypertension, tachycardia, and increased cardiac output. This was useful in the animal who could fight or flee; but in the person who could do neither by virtue of being civilized, the ensuing stress resulted in disease (e.g., produced a cardiovascular disorder).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree