Psychotherapies

28.1 Psychoanalysis and Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy

28.1 Psychoanalysis and Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy

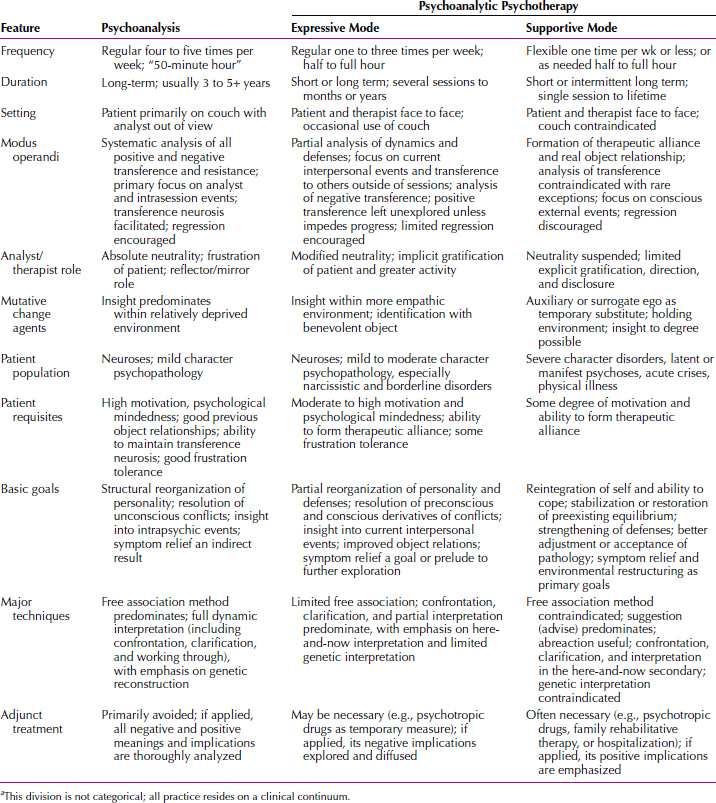

As broadly practiced today, psychoanalytic treatment encompasses a wide range of uncovering strategies used in varied degrees and blends. Despite the inevitable blurring of boundaries in actual application, the original modality of classic psychoanalysis and major modes of psychoanalytic psychotherapy (expressive and supportive) are delineated separately here (Table 28.1-1). Analytical practice in all its complexity resides on a continuum. Individual technique is always a matter of emphasis, as the therapist titrates the treatment according to the needs and capacities of the patient at every moment.

Table 28.1-1

Table 28.1-1

Scope of Psychoanalytic Practice: A Clinical Continuuma

Psychoanalysis is virtually synonymous with the renowned name of its founding father, Sigmund Freud (Freud and his theories are discussed in Section 4.1). It is also referred to as “classic” or “orthodox” psychoanalysis to distinguish it from more recent variations known as psychoanalytic psychotherapy (discussed below).

Psychoanalysis is based on the theory of sexual repression and traces the unfulfilled infantile libidinal wishes in the individual’s unconscious memories. It remains unsurpassed as a method to discover the meaning and motivation of behavior, especially the unconscious elements that inform thoughts and feelings.

PSYCHOANALYSIS

Psychoanalytic Process

The psychoanalytic process involves bringing to the surface repressed memories and feelings by means of a scrupulous unraveling of hidden meanings of verbalized material and of the unwitting ways in which the patient wards off underlying conflicts through defensive forgetting and repetition of the past.

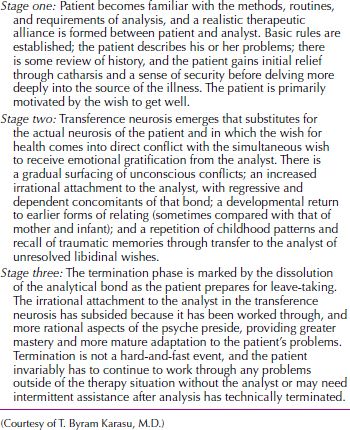

The overall process of analysis is one in which unconscious neurotic conflicts are recovered from memory and verbally expressed, reexperienced in the transference, reconstructed by the analyst, and, ultimately, resolved through understanding. Freud referred to these processes as recollection, repetition, and working through, which make up the totality of remembering, reliving, and gaining insight. Recollection entails the extension of memory back to early childhood events, a time in the distant past when the core of neurosis was formed. The actual reconstruction of these events comes through reminiscence, associations, and autobiographical linking of developmental events. Repetition involves more than mere mental recall; it is an emotional replay of former interactions with significant individuals in the patient’s life. The replay occurs within the special context of the analyst as projected parent, a fantasized object from the patient’s past with whom the latter unwittingly reproduces forgotten, unresolved feelings and experiences from childhood. Finally, working through is both an affective and cognitive integration of previously repressed memories that have been brought into consciousness and through which the patient is gradually set free (cured of neurosis). The analytical course can be subdivided into three major stages (Table 28.1-2).

Table 28.1-2

Table 28.1-2

Stages of Psychoanalysis

Indications and Contraindications

In general, all of the so-called psychoneuroses are suitable for psychoanalysis. These include anxiety disorders, obsessional thinking, compulsive behavior, conversion disorder, sexual dysfunction, depressive states, and many other nonpsychotic conditions, such as personality disorders. Significant suffering must be present so that patients are motivated to make the sacrifices of time and financial resources required for psychoanalysis. Patients who enter analysis must have a genuine wish to understand themselves, not a desperate hunger for symptomatic relief. They must be able to withstand frustration, anxiety, and other strong affects that emerge in analysis without fleeing or acting out their feelings in a self-destructive manner. They must also have a reasonable, mature superego that allows them to be honest with the analyst. Intelligence must be at least average, and above all, they must be psychologically minded in the sense that they can think abstractly and symbolically about the unconscious meanings of their behavior.

Many contraindications for psychoanalysis are the flip side of the indications. The absence of suffering, poor impulse control, inability to tolerate frustration and anxiety, and low motivation to understand are all contraindications. The presence of extreme dishonesty or antisocial personality disorder contraindicates analytic treatment. Concrete thinking or the absence of psychological mindedness is another contraindication. Some patients who might ordinarily be psychologically minded are not suitable for analysis because they are in the midst of a major upheaval or life crisis, such as a job loss or a divorce. Serious physical illness can also interfere with a person’s ability to invest in a long-term treatment process. Patients of low intelligence generally do not understand the procedure or cooperate in the process. An age older than 40 years was once considered a contraindication, but today analysts recognize that patients are malleable and analyzable in their 60s or 70s. One final contraindication is a close relationship with the analyst. Analysts should avoid analyzing friends, relatives, or persons with whom they have other involvements.

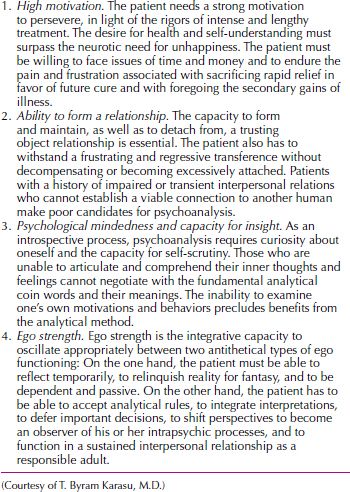

Patient Requisites

The most important patient requisites for psychoanalysis are listed in Table 28.1-3.

Table 28.1-3

Table 28.1-3

Patient Prerequisites for Psychoanalysis

Ms. M, a 29-year-old unmarried woman who worked in a low-level capacity for a magazine, presented for consultation with the chief complaints of considerable sadness and distress over her parent’s reaction when they found that she had had a homosexual relationship. She also realized that she had been working far below her potential. She had never sought any treatment before. She was clearly intelligent, sensitive, self-reflective, and insightful. When the possibility of psychoanalysis was presented to her, she worried that meant she was “sicker.” Ms. M, however, began reading Freud, realized that analysis was actually recommended for those who are higher functioning, and became intrigued by the idea. She agreed to come 4 days a week for 50-minute sessions.

She was the oldest of three children and the only girl. Ms. M’s father, a successful professional, was described as very demanding and intrusive, someone who never thought anything was good enough. He had always expected his children to do the “extra credit” assignments as part of their regular work. Ms. M, however, was very proud of her father’s accomplishments. She spoke of her mother in conflicting terms as well: She was a homemaker, weak, and sometimes acquiescent to the powerful father but also a woman in her own right who was involved in community volunteer work and could be a powerful public speaker.

Just prior to beginning her analysis, Ms. M had had her wallet stolen. In her first analytic session, she spoke of losing all of her identification cards, and to her it seemed as if she were starting analysis “with a completely new identity.” Initially, she was somewhat hesitant to use the couch because she wanted to see her analyst’s reactions, but she quickly appreciated that she could associate more easily without seeing the analyst.

As her analysis proceeded, through dreams and free associations, Ms. M became quite focused on the analyst. She became extremely curious about the analyst’s life. What emerged from her associations to seeing the analyst’s appointment book on the desk was that she felt “slotted in.” Whenever Ms. M saw other patients, she felt the office was “like an assembly line.” Further associations led to her feeling slotted in by her parents as they ran from one activity to another. Her resistance manifested itself in Ms. M’s often coming as much or more than 15 minutes late to her sessions. Her associations led to her admitting that she did not want her analyst to think that she was “too eager.” Ms. M was able to see that she needed to devalue her analyst and her importance to Ms. M as a defense against an overwhelming positive and even erotic transference toward her.

For example, Ms. M wanted to improve her appearance so that the therapist, who she called a “role model,” would find her more attractive. Her negative transference, however, was never far from the surface, and she denigrated the analyst by wondering if the analyst were a “clotheshorse” who was financing her wardrobe with the patient’s payments.

Her conflicts about her sexual orientation were a central preoccupation in the course of her analysis, particularly because her father was so homophobic. Early on, Ms. M felt awkward and uncomfortable when she went to a lesbian bar, and when asked if she qualified for the “lesbian discount,” she said she did not. At one point, she began seeing several men, including a male psychologist. The analyst made the transference interpretation, which Ms. M accepted, that a date with this man seemed as if it were a date with the analyst and sleeping with him would be equivalent to sleeping with the analyst. Ms. M was also able to see that her transient choice of dating a male therapist was a defensive compromise. Although her homosexual object choice was multidetermined, Ms. M came to appreciate, through her work in analysis, that at least a part of her conflicts about homosexuality stemmed from her relationship toward her father. It was a means of securing his attention as well as infuriating him.

Over the course of 4 years, Ms. M began to do considerably better at work and was promoted to a job commensurate with her potential. She was also able to deal better with both her parents, and particularly her father, regarding her sexual orientation. She became much more comfortable with her “new identity” and became involved in a relationship with a professional woman. At the end of therapy, Ms. M and this woman were committed to each other and were thinking of adopting a child. (Courtesy of T. Byram Karasu, M.D., and S. R. Karasu, M.D.)

Goals

Stated in developmental terms, psychoanalysis aims at the gradual removal of amnesias rooted in early childhood based on the assumption that when all gaps in memory have been filled, the morbid condition will cease because the patient no longer needs to repeat or remain fixated to the past. The patient should be better able to relinquish former regressive patterns and to develop new, more adaptive ones, particularly as he or she learns the reasons for his or her behavior. A related goal of psychoanalysis is for the patient to achieve some measure of self-understanding or insight.

Psychoanalytic goals are often considered formidable (e.g., a total personality change), involving the radical reorganization of old developmental patterns based on earlier affects and the entrenched defenses built up against them. Goals may also be elusive, framed as they are in theoretical intrapsychic terms (e.g., greater ego strength) or conceptually ambiguous ones (resolution of the transference neurosis). Criteria for successful psychoanalysis may be largely intangible and subjective and they are best regarded as conceptual endpoints of treatment that must be translated into more realistic and practical terms.

In practice, the goals of psychoanalysis for any patient naturally vary, as do the many manifestations of neuroses. The form that the neurosis takes—unsatisfactory sexual or object relationships, inability to enjoy life, underachievement, and fear of work or academic success, or excessive anxiety, guilt, or depressive ideation—determines the focus of attention and the general direction of treatment, as well as the specific goals. Such goals may change at any time during the course of analysis, especially as many years of treatment may be involved.

Major Approach and Techniques

Structurally, psychoanalysis usually refers to individual (dyadic) treatment that is frequent (four or five times per week) and long term (several years). All three features take their precedent from Freud himself.

The dyadic arrangement is a direct function of the Freudian theory of neurosis as an intrapsychic phenomenon, which takes place within the person as instinctual impulses continually seek discharge. Because dynamic conflicts must be internally resolved if structural personality reorganization is to take place, the individual’s memory and perceptions of the repressed past are pivotal.

Freud initially saw patients 6 days a week for 1 hour each day, a routine now reduced to four or five sessions per week of the classic 50-minute hour, which leaves time for the analyst to take notes and organize relevant thoughts before the next patient. Long intervals between sessions are avoided so that the momentum gained in uncovering conflictual material is not lost and confronted defenses do not have time to restrengthen.

Freud’s belief that successful psychoanalysis always takes a long time because profound changes in the mind occur slowly still holds. The process can be likened to the fluid sense of time that is characteristic of our unconscious processes. Moreover, because psychoanalysis involves a detailed recapitulation of present and past events, any compromise in time presents the risk of losing pace with the patient’s mental life.

Psychoanalytic Setting. As with other forms of psychotherapy, psychoanalysis takes place in a professional setting, apart from the realities of everyday life, in which the patient is offered a temporary sanctuary in which to ease psychic pain and reveal intimate thoughts to an accepting expert. The psychoanalytic environment is designed to promote relaxation and regression. The setting is usually spartan and sensorially neutral, and external stimuli are minimized.

USE OF THE COUCH. The couch has several clinical advantages that are both real and symbolic: (1) the reclining position is relaxing because it is associated with sleep and so eases the patient’s conscious control of thoughts; (2) it minimizes the intrusive influence of the analyst, thus curbing unnecessary cues; (3) it permits the analyst to make observations of the patient without interruption; and (4) it holds symbolic value for both parties, a tangible reminder of the Freudian legacy that gives credibility to the analyst’s professional identity, allegiance, and expertise. The reclining position of the patient with analyst nearby can also generate threat and discomfort, however, as it recalls anxieties derived from the earlier parent–child configuration that it physically resembles. It may also have personal meanings—for some, a portent of dangerous impulses or of submission to an authority figure; for others, a relief from confrontation by the analyst (e.g., fear of use of the couch and overeagerness to lie down may reflect resistance and, thus, need to be analyzed). Although the use of the couch is requisite to analytical technique, it is not applied automatically; it is introduced gradually and can be suspended whenever additional regression is unnecessary or counter-therapeutic.

FUNDAMENTAL RULE. The fundamental rule of free association requires patients to tell the analyst everything that comes into their heads—however disagreeable, unimportant, or nonsensical—and to let themselves go as they would in a conversation that leads from “cabbages to kings.” It differs decidedly from ordinary conversation—instead of connecting personal remarks with a rational thread, the patient is asked to reveal those very thoughts and events that are objectionable precisely because of being averse to doing so.

This directive represents an ideal because free association does not arise freely but is guided and inhibited by a variety of conscious and unconscious forces. The analyst must not only encourage free association through the physical setting and a nonjudgmental attitude toward the patient’s verbalizations, but also examine those very instances when the flow of associations is diminished or comes to a halt—they are as important analytically as the content of the associations. The analyst should also be alert to how individual patients use or misuse the fundamental rule.

Aside from its primary purpose of eliciting recall of deeply hidden early memories, the fundamental rule reflects the analytical priority placed on verbalization, which translates the patient’s thoughts into words so they are not channeled physically or behaviorally. As a direct concomitant of the fundamental rule, which prohibits action in favor of verbal expression, patients are expected to postpone making major alterations in their lives, such as marrying or changing careers, until they discuss and analyze them within the context of treatment.

PRINCIPLE OF EVENLY SUSPENDED ATTENTION. As a reciprocal corollary to the rule that patients communicate everything that occurs to them without criticism or selection, the principle of evenly suspended attention requires the analyst to suspend judgment and to give impartial attention to every detail equally. The method consists simply of making no effort to concentrate on anything specific, while maintaining a neutral, quiet attentiveness to all that is said.

ANALYST AS MIRROR. A second principle is the recommendation that the analyst be impenetrable to the patient and, as a mirror, reflect only what is shown. Analysts are advised to be neutral blank screens and not to bring their own personalities into treatment. This means that they are not to bring their own values or attitudes into the discussion or to share personal reactions or mutual conflicts with their patients, although they may sometimes be tempted to do so. The bringing in of reality and external influences can interrupt or bias the patient’s unconscious projections. Neutrality also allows the analyst to accept without censure all forbidden or objectionable responses.

RULE OF ABSTINENCE. The fundamental rule of abstinence does not mean corporal or sexual abstinence, but refers to the frustration of emotional needs and wishes that the patient may have toward the analyst or part of the transference. It allows the patient’s longings to persist and serve as driving forces for analytical work and motivation to change. Freud advised that the analyst carry through the analytical treatment in a state of renunciation. The analyst must deny the patient who is longing for love the satisfaction he or she craves.

Limitations. At present, the predominant treatment constraints are often economic, relating to the high cost in time and money, both for patients and in the training of future practitioners. In addition, because clinical requirements emphasize such requisites as psychological mindedness, verbal and cognitive ability, and stable life situation, psychoanalysis may be unduly restricted to a diagnostically, socioeconomically, or intellectually advantaged patient population. Other intrinsic issues pertain to the use and misuse of its stringent rules, whereby overemphasis on technique may interfere with an authentic human encounter between analyst and patient, and to the major long-term risk of interminability, in which protracted treatment may become a substitute for life. Reification of the classic analytical tradition may interfere with a more open and flexible application of its tenets to meet changing needs. It may also obstruct a comprehensive view of patient care that includes a greater appreciation of other treatment modalities in conjunction with, or as an alternative to, psychoanalysis.

Ms. A, a 25-year-old articulate and introspective medical student, began analysis complaining of mild, chronic anxiety, dysphoria, and a sense of inadequacy, despite above-average intelligence and performance. She also expressed difficulty in long-term relationships with her male peers.

Ms. A began the initial phase of analysis with enthusiastic self-disclosure, frequent reports of dreams and fantasies, and overidealization of the analyst; she tried to please him by being a compliant, good patient, just as she had been a good daughter to her father (a professor of medicine) by going to medical school.

Over the next several months, Ms. A gradually developed a strong attachment to the analyst and settled into a phase of excessive preoccupation with him. Simultaneously, however, she began dating an older psychiatrist and proceeded to complain about the analyst’s coldness and unresponsiveness, even considering dropping out of analysis because he did not meet her demands.

In the course of analysis, through dreams and associations, Ms. A recalled early memories of her ongoing competition with her mother for her father’s attention and realized that, failing to obtain his exclusive love, she had tried to become like him. She was also able to see how her increasing interest in becoming a psychiatrist (rather than following her original plan to be a pediatrician), as well as her recent choice of a man to date, were recapitulations of the past vis-à-vis the analyst. As this repeated pattern was recognized, the patient began to relinquish her intense erotic and dependent tie to the analyst, viewing him more realistically and beginning to appreciate the ways in which his quiet presence reminded her of her mother. She also became less disturbed by the similarities she shared with her mother and was able to disengage from her father more comfortably. By the fifth year of analysis, she was happily married to a classmate, was pregnant, and was a pediatric chief resident. Her anxiety was now attenuated and situation specific (that is, she was concerned about motherhood and the termination of analysis). (Courtesy of T. Byram Karasu, M.D.)

PSYCHOANALYTIC PSYCHOTHERAPY

Psychoanalytic psychotherapy, which is based on fundamental dynamic formulations and techniques that derive from psychoanalysis, is designed to broaden its scope. Psychoanalytic psychotherapy, in its narrowest sense, is the use of insight-oriented methods only. As generically applied today to an ever-larger clinical spectrum, it incorporates a blend of uncovering and suppressive measures.

The strategies of psychoanalytic psychotherapy currently range from expressive (insight-oriented, uncovering, evocative, or interpretive) techniques to supportive (relationship-oriented, suggestive, suppressive, or repressive) techniques. Although those two types of methods are sometimes regarded as antithetical, their precise definitions and the distinctions between them are by no means absolute.

The duration of psychoanalytic psychotherapy is generally shorter and more variable than in psychoanalysis. Treatment may be brief, even with an initially agreed-upon or fixed time limit, or may extend to a less definite number of months or years. Brief treatment is chiefly used for selected problems or highly focused conflict, whereas longer treatment may be applied for more chronic conditions or for intermittent episodes that require ongoing attention to deal with pervasive conflict or recurrent decompensation. Unlike psychoanalysis, psychoanalytic psychotherapy rarely uses the couch; instead, patient and therapist sit face to face. This posture helps to prevent regression because it encourages the patient to look on the therapist as a real person from whom to receive direct cues, even though transference and fantasy will continue. The couch is considered unnecessary because the free-association method is rarely used, except when the therapist wishes to gain access to fantasy material or dreams to enlighten a particular issue.

Expressive Psychotherapy

Indications and Contraindications. Diagnostically, psychoanalytic psychotherapy in its expressive mode is suited to a range of psychopathology with mild to moderate ego weakening, including neurotic conflicts, symptom complexes, reactive conditions, and the whole realm of nonpsychotic character disorders, including those disorders of the self that are among the more transient and less profound on the severity-of-illness spectrum, such as narcissistic behavior disorders and narcissistic personality disorders. It is also one of the treatments recommended for patients with borderline personality disorders, although special variations may be required to deal with the associated turbulent personality characteristics, primitive defense mechanisms, tendencies toward regressive episodes, and irrational attachments to the analyst.

Ms. B, an intelligent and verbal 34-year-old divorced woman, presented with complaints of being unappreciated at work. Always angry and irritable, she considered quitting her job and even leaving the city. Her social life was also being negatively affected; her boyfriend had threatened to leave her because of her extremely hostile, clinging behavior (the same reason her ex-husband had given when he left her 9 years earlier after only 16 months of marriage).

Her past included promiscuity and experimentation with various drugs, and, currently, she indulged in heavy drinking on weekends and occasionally smoked marijuana. She had held many jobs and had lived in various cities. The eldest of three children of a middle-class family, she came from an unhappy and unstable home: her brother had been in and out of psychiatric hospitals; her sister had left home at the age of 16 after becoming pregnant and being forced to marry; and her overly controlling parents had subjected their children to psychological (and occasionally physical) abuse, alternating between heated arguments and passionate reconciliations.

Initially, Ms. B attempted to contain her rage in treatment, but it frequently surfaced and alternated with child-like helplessness; she interrogated the psychiatrist regarding his credentials, ridiculed psychodynamic concepts, constantly challenged statements, and would demand practical advice but then denigrate or fail to follow the guidance given. The psychiatrist remained unprovoked by her aggression and explored with her the need to engage him negatively. Her response was to question and test his continued concern.

When her boyfriend left her, she attempted suicide (she cut her wrists superficially), was briefly hospitalized, and, on discharge, was placed on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for 6 months for her minor, but protracted, depression. The psychiatrist maintained their regular frequency of sessions despite her greater demands. Although she was puzzled by the steadiness of his interest, she gradually felt safe enough to express her vulnerabilities. As they explored her lack of full commitment to work, friends, and therapy, she began to understand the meaning of her anger in terms of the early abusive relationship with her parents and her tendency to bring it into contemporary relationships. With the psychiatrist’s encouragement, she also began to seek work and make small strides in relationship-oriented efforts. By the end of her second year of treatment, she had decided to remain in the city, to stay at her place of employment, and to continue therapy. She needed to experience and practice her somewhat fragile new self, which included greater intimacy in relationships, additional mastery of work skills, and a more cohesive sense of self. (Courtesy of T. Byram Karasu, M.D.)

The persons best suited for the expressive psychotherapy approach have fairly well integrated egos and the capacity to both sustain and detach from a bond of dependency and trust. They are, to some degree, psychologically minded and self-motivated, and they are generally able, at least temporarily, to tolerate doses of frustration without decompensating. They must also have the ability to manage the rearousal of painful feelings outside the therapy hour without additional contact. Patients must have some capacity for introspection and impulse control, and they should be able to recognize the cognitive distinction between fantasy and reality.

Goals. The overall goals of expressive psychotherapy are to increase the patient’s self-awareness and to improve object relations through exploration of current interpersonal events and perceptions. In contrast to psychoanalysis, major structural changes in ego function and defenses are modified in light of patient limitations. The aim is to achieve a more limited and, thus, select and focused understanding of one’s problems. Rather than uncovering deeply hidden and past motives and tracing them back to their origins in infancy, the major thrust is to deal with preconscious or conscious derivatives of conflicts as they became manifest in present interactions. Although insight is sought, it is less extensive; instead of delving to a genetic level, greater emphasis is on clarifying recent dynamic patterns and maladaptive behaviors in the present.

Major Approach and Techniques. The major modus operandi involves establishment of a therapeutic alliance and early recognition and interpretation of negative transference. Only limited or controlled regression is encouraged, and positive transference manifestations are generally left unexplored, unless they are impeding therapeutic progress; even here, the emphasis is on shedding light on current dynamic patterns and defenses.

Limitations. A general limitation of expressive psychotherapy, as of psychoanalysis, is the problem of emotional integration of cognitive awareness. The major danger for patients who are at the more disorganized end of the diagnostic spectrum, however, may have less to do with the overintellectualization that is sometimes seen in neurotic patients than with the threat of decompensation from, or acting out of, deep or frequent interpretations that the patient is unable to integrate properly.

Some therapists fail to accept the limitations of a modified insight-oriented approach and so apply it inappropriately to modulate the techniques and goals of psychoanalysis. Overemphasis on dreams and fantasies, zealous efforts to use the couch, indiscriminate deep interpretations, and continual focus on the analysis of transference may have less to do with the patient’s needs than with those of a therapist who is unwilling or unable to be flexible.

Ms. S was an attractive 30-year-old unmarried woman working as a secretary when she presented for consultation. Her chief complaints at the time were feeling “only anger and tension” and an inability to apply herself to studying voice, “which is one of the most important things to me.”

In obtaining a history, the therapist noted that Ms. S had never completed anything: She had dropped out of college; never pursued a music degree; and switched from job to job, and even city to city. What initially seemed like a woman with diverse interests (e.g., jobs as a research assistant, freelance copyeditor, part-time radio announcer; manager of data entry for a software company; and, most recently, secretary) really reflected a woman with a chaotic lifestyle and serious difficulties committing to anyone or anything. Although obviously intelligent, Ms. S presented with unrealistic expectations regarding her consultation. For example, after the first consultative session, Ms. S said she felt good afterward but felt there were “no revelations yet.” Because of Ms. S’s inability to commit and her somewhat disorganized life, the therapist recommended a course of psychotherapy, beginning twice a week, rather than something more intense like psychoanalysis. The therapist also realized over the course of the consultation that Ms. S would have difficulty with free association without getting disorganized. The therapist also thought that Ms. S might regress unproductively on the couch without visual contact with the therapist.

Ms. S was the second oldest of four children—two brothers and a younger sister, with whom she was most competitive and who clearly seemed the mother’s favorite. She described her mother as a successful professor who was demanding and critical, as if she had a “raised eyebrow” in disapproval. For example, much to her mother’s chagrin, Ms. S had once wanted a sandwich “with everything on it.” Ms. S was also disappointed when she was given one piece of luggage rather than a complete set for a Christmas gift. She was able to accept the therapist’s interpretation that she felt “part of a set” by being one of four siblings. Ms. S initially idealized her father, who was active in the family church, but eventually saw him as disappointing and rejecting.

Ms. S’s ideal therapist would be “flexible,” by which she meant a therapist who might do hypnosis one session, psychotherapy the next, and, maybe, analysis another session. In fact, within the first week of beginning therapy, Ms. S had simultaneously consulted a hypnotherapist, which she mentioned in passing only weeks later, for her neck pain and tension. Although she did not pursue hypnosis, she did maintain a chiropractor for most of her therapy, also something she mentioned many months after beginning therapy. She did speak of wanting to be “on best behavior” and “follow the rules.” Her tremendous sense of entitlement, however, was evident: She had an expectation of getting “cut-rate prices” on everything from haircuts and car repairs to doctors’ visits. Her initial fee was a much-reduced one, which she paid late and begrudgingly.

Although she was seen only twice a week, Ms. S developed intense feelings for her therapist. Mostly she experienced rage when she saw evidence of the therapist’s other patients, such as footprints on the waiting room floor after a snowstorm or a coat hanger turned around. She expressed the wish to keep some of her things, like bobby pins and hairspray, in the therapist’s bathroom. She vacillated between feelings she wanted to move in and feelings that the therapist did not exist. For example, before she took a plane flight, she wondered who would tell her therapist if something happened to her. She had never given the therapist’s name to anyone, nor did she have her name in her weekly appointment book. The therapist interpreted that she had a simultaneous wish to devalue her and not to share her with anyone else. Associations to a dream with an image of a string of baroque pearls led to thoughts that these pearls—irregular and imperfect—defective and even lopsided, represented how she viewed herself.

Over the course of the next few years, Ms. S was able to commit to coming regularly to therapy, although the course was somewhat tumultuous, with many threats of quitting and much withholding of information. At one point, she even tried to provoke the therapist by seeking a consultation with another therapist in order to “tattle” on her, just as she had tattled on her siblings. Her therapist remained unprovoked and continued to provide a safe environment for Ms. S to explore her ambivalence to the therapist and the therapeutic situation. The therapist was also able to contain Ms. S’s tendency to regress, particularly with separations, by providing her with the therapist’s telephone number.

She had actually entered therapy with an unconscious wish to become a world-famous singer who would win her mother’s approval and praise. Her narcissism and sense of entitlement made it difficult for her to give up on that fantasy despite repeated evidence that she did not have sufficient talent. She was finally able to settle on a compromise: She began to work diligently and closely as a research assistant to her mother, who was writing a book, and as Ms. S became more focused and organized over time, she even thought she might write a book about the church. (Courtesy of T. Byram Karasu, M.D., and S. R. Karasu, M.D.)

Supportive Psychotherapy

Supportive psychotherapy aims at the creation of a therapeutic relationship as a temporary buttress or bridge for the deficient patient. It has roots in virtually every therapy that recognizes the ameliorative effects of emotional support and a stable, caring atmosphere in the management of patients. As a nonspecific attitude toward mental illness, it predates scientific psychiatry, with foundations in 18th-century moral treatment, whereby for the first time patients were treated with understanding and kindness in a humane, interpersonal environment free from mechanical restraints.

Supportive psychotherapy has been the chief form used in the general practice of medicine and rehabilitation, frequently to augment extratherapeutic measures, such as prescriptions of medication to suppress symptoms, rest to remove the patient from excessive stimulation, or hospitalization to provide a structured therapeutic environment, protection, and control of the patient. It can be applied as primary or ancillary treatment. The global perspective of supportive psychotherapy (often part of a combined treatment approach) places major etiological emphasis on external rather than intrapsychic events, particularly on stressful environmental and interpersonal influences on a severely damaged self.

Indications and Contraindications. Supportive psychotherapy is generally indicated for those patients for whom classic psychoanalysis or insight-oriented psychoanalytic psychotherapy is typically contraindicated—those who have poor ego strength and whose potential for decompensation is high. Amenable patients fall into the following major areas: (1) individuals in acute crisis or a temporary state of disorganization and inability to cope (including those who might otherwise be well functioning) whose intolerable life circumstances have produced extreme anxiety or sudden turmoil (e.g., individuals going through grief reactions, illness, divorce, job loss, or who were victims of crime, abuse, natural disaster, or accident); (2) patients with chronic severe pathology with fragile or deficient ego functioning (e.g., those with latent psychosis, impulse disorder, or severe character disturbance); (3) patients whose cognitive deficits and physical symptoms make them particularly vulnerable and, thus, unsuitable for an insight-oriented approach (e.g., certain psychosomatic or medically ill persons); and (4) individuals who are psychologically unmotivated, although not necessarily characterologically resistant to a depth approach (e.g., patients who come to treatment in response to family or agency pressure and are interested only in immediate relief or those who need assistance in very specific problem areas of social adjustment as a possible prelude to more exploratory work).

Mr. C, a 50-year-old married man with two sons, the owner of a small construction company, was referred by his internist after recovery from bypass surgery because of frequent, unfounded physical complaints. He was taking minor tranquilizers in increasing doses, not complying with his daily regimen, avoiding sexual contact with his wife, and had dropped out of group therapy for postsurgical patients after one session.

He came to his first appointment 20 minutes late, after having “forgotten” two previous appointments. He was extremely anxious, often lost in his train of thought, and was semidelusional about his wife and sons, suggesting that they might want to have him locked up. He briefly told his life history, which included his coming from a strict and hard-working but caring middle-class family and the death of his mother when he was only 11 years old. He had joined his father’s business (taking over after his father’s death 2 years earlier), with both of his sons as associates. Describing himself as successful in work and marriage, he claimed that “the only test I ever failed was the stress test.”

Mr. C explained his lack of compliance with diet restrictions as a lack of will and his constant contact with the internist as his having real physical problems not yet diagnosed; he rejected the idea of addiction to tranquilizers, insisting that he could quit any time. He had no fantasy life, remembered no dreams, made it clear that he had entered treatment on his internist’s instruction only, and started each session by stating that he had nothing to talk about.

After suggesting that Mr. C was coming to sessions just to pass the “sanity test” and that there was no reason to have him locked up, the psychiatrist encouraged the patient to join him in figuring out the real reasons for his anxiety. Initial sessions were devoted to discussing the patient’s medical condition and providing factual information about heart and bypass surgery. The therapist likened the patient’s condition to that of an older house getting new plumbing, trying to allay his unrealistic fears of impending death. As Mr. C’s anxiety declined, he became less defensive and more psychologically accessible. As the therapist began to explore his difficulty in accepting help, Mr. C was able to talk about his inability to admit problems (i.e., weaknesses). The therapist’s explicit recognition of the patient’s strength in admitting his weaknesses encouraged the patient to reveal more about himself—how he had welcomed his father’s death and his belief that perhaps his illness was punishment. The psychiatrist also encouraged him to speak about his unrealistic guilt and, at the same time, helped him recognize his suspicion of his sons as the reflection of his own wishes concerning his father and his lack of commitment to his medical regimen as a wish to die so as to expiate guilt. After steady urging by the therapist, Mr. C returned to work. He agreed to meet monthly with the psychiatrist and to taper off his use of tranquilizers. He even agreed that he might see the psychiatrist for “deep analysis” in the future because his wife now jokingly complained of his obsessive dieting, his uncompromising exercise regimens, and his regularly scheduled sexual activities. (Courtesy of T. Byram Karasu, M.D.)

Because support forms a tacit part of every therapeutic modality, it is rarely contraindicated as such. The typical attitude regards better-functioning patients as unsuitable not because they will be harmed by a supportive approach, but because they will not be sufficiently benefited by it. In aiming to maximize the patient’s potential for further growth and change, supportive therapy tends to be regarded as relatively restricted and superficial and, thus, is not recommended as the treatment of choice if the patient is available for, and capable of, a more in-depth approach.

Goals. The general aim of supportive treatment is the amelioration or relief of symptoms through behavioral or environmental restructuring within the existing psychic framework. This often means helping the patient to adapt better to problems and to live more comfortably with his or her psychopathology. To restore the disorganized, fragile, or decompensated patient to a state of relative equilibrium, the major goal is to suppress or control symptomatology and to stabilize the patient in a protective and reassuring benign atmosphere that militates against overwhelming external and internal pressures. The ultimate goal is to maximize the integrative or adaptive capacities so that the patient increases the ability to cope, while decreasing vulnerability by reinforcing assets and strengthening defenses.

Major Approach and Techniques. Supportive therapy uses several methods, either singly or in combination, including warm, friendly, strong leadership; partial gratification of dependency needs; support in the ultimate development of legitimate independence; help in developing pleasurable activities (e.g., hobbies); adequate rest and diversion; removal of excessive strain, when possible; hospitalization, when indicated; medication to alleviate symptoms; and guidance and advice in dealing with current issues. This therapy uses techniques to help patients feel secure, accepted, protected, encouraged, safe, and not anxious.

Limitations. To the extent that much supportive therapy is spent on practical, everyday realities and on dealing with the external environment of the patient, it may be viewed as more mundane and superficial than depth approaches. Because those patients are seen intermittently and less frequently, the interpersonal commitment may not be as compelling on the part of either the patient or the therapist. Greater severity of illness (and possible psychoses) also makes such treatment potentially more erratic, demanding, and frustrating. The need for the therapist to deal with other family members, caretakers, or agencies (auxiliary treatment, hospitalization) can become an additional complication, because the therapist comes to serve as an ombudsman to negotiate with the outside world of the patient and with other professional peers. Finally, the supportive therapist must be able to accept personal limitations and the patient’s limited psychological resources and to tolerate the often unrewarded efforts until small gains are made.

Mr. W was a 42-year-old widowed businessman who was referred by his internist because of the sudden death of his wife, who had had an intracranial hemorrhage, about 2 months earlier. Mr. W had two children, a boy and a girl, ages 10 and 8 years, respectively.

Mr. W had never been to a psychiatrist before, and when he arrived he admitted he was not certain what a psychiatrist could do for him. He just had to get over his wife’s death. He was not sure how talking about anything could really help. He had been married for 15 years. He admitted to having difficulty sleeping, particularly awakening in the middle of the night with considerable anxiety about the future. One of his relatives had given him some of her own Klonopin for his anxiety, which helped tremendously, but he feared getting dependent on it. He was also drinking more than he thought he should. He was most concerned about raising his children alone and felt somewhat overwhelmed by the responsibility. He was beginning to appreciate just how wonderful a mother his wife had been and now saw how critical he had been of her for spending so much time with the children. “It really does take a lot of effort,” he said.

Mr. W did admit to feelings of guilt. For one thing, he admitted to some sense that he could now start over. He had been somewhat restless in the marriage recently before his wife’s death and had actually been unfaithful for a brief period early in the marriage. He also felt some guilt that had he been awake the night of his wife’s hemorrhage, maybe he could have saved his wife. In reality, there was nothing he could have done.

Mr. W agreed to come for a few sessions to talk about his wife. At this point, only 2 months after her death, he seemed to have an uncomplicated mourning reaction. Although he talked easily in session, he was clearly worried that he might like “being here too much.” The therapist chose not to interpret his dependency conflicts. Mr. W seemed to have good coping skills and used humor as a high-functioning defense. For example, in giving a eulogy for his wife (who had been a very popular member of their congregation), he looked around at the enormous crowd of people at the church service and said he had never seen so many people attending church before, adding, “Sorry, Reverend.”

After about four sessions, Mr. W said he that felt better and no longer saw the need for further sessions. He was sleeping better and had stopped drinking excessively. The therapist suggested that he might want to continue to talk more about his guilt and his life as he went forward without his wife. The therapist was also reassuring that there seemed to be nothing else Mr. W could have done to save his wife. He also encouraged the patient to begin dating when he felt ready, something that Mr. W’s in-laws were clearly not encouraging. For now, however, Mr. W was not interested in any further therapy. He was appreciative of the therapist and felt that talking about his wife’s death had been helpful. The therapist accepted his wish to discontinue their sessions but encouraged Mr. W to keep in touch to let him know how he was doing. (Courtesy of T. Byram Karasu, M.D., and S. R. Karasu, M.D.)

CORRECTIVE EMOTIONAL EXPERIENCE. The relationship between therapist and patient gives a therapist an opportunity to display behavior different from the destructive or unproductive behavior of a patient’s parent. At times, such experiences seem to neutralize or reverse some effects of the parents’ mistakes. If the patient had overly authoritarian parents, the therapist’s friendly, flexible, nonjudgmental, nonauthoritarian—but at times firm and limit setting—attitude gives the patient an opportunity to adjust to, be led by, and identify with a new parent figure. Franz Alexander described this process as a corrective emotional experience. It draws on elements of both psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic psychotherapy.

REFERENCES

Buckley P. Revolution and evolution: A brief intellectual history of American psychoanalysis during the past two decades. Am J Psychother. 2003;57:1–17.

Canestri J. Some reflections on the use and meaning of conflict in contemporary psychoanalysis. Psychoanal Q. 2005;74(1):295–326.

Dodds J. Minding the ecological body: Neuropsychoanalysis and ecopsychoanalysis. Front Psychol. 2013;4:125.

Joannidis C. Psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic psychotherapy. Psychoanal Psychother. 2006;20(1):30–39.

Kandel ER. Psychiatry, Psychoanalysis, and the New Biology of Mind. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2005.

Karasu TB. The Art of Serenity. New York: Simon and Schuster; 2003.

Karasu TB, Karasu SR. Psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic psychotherapy. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, eds. Kaplan & Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:2746.

McWilliams N. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy: A Practitioner’s Guide. New York: Guilford; 2004.

Person ES, Cooper AM, Gabbard GO, eds. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychoanalysis. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2005.

Roseneil S. Beyond ‘the relationship between the individual and society’: Broadening and deepening relational thinking in group analysis. Group Anal. 2013;46(2):196–210.

Shulman DG. The analyst’s equilibrium, countertransferential management, and the action of psychoanalysis. Psychoanal Rev. 2005;92(3):469–478.

Siegel E. Psychoanalysis as a traditional form of knowledge: An inquiry into the methods of psychoanalysis. Int J Appl Psychoanal Stud. 2006;2(2):146–163.

Strenger C. The Designed Self: Psychoanalysis and Contemporary Identities. Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press; 2005.

Tummala-Narra P. Psychoanalytic applications in a diverse society. Psychoanal Psychol. 2013;30(3):471–487.

Unit P. Mentalization-based treatment for psychosis: Linking an attachment-based model to the psychotherapy for impaired mental state understanding in people with psychotic disorders. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2014;51(1).

Varvin S. Which patients should avoid psychoanalysis, and which professionals should avoid psychoanalytic training? A critical evaluation. Scand Psychoanal Rev. 2003;26:109–122.

28.2 Brief Psychodynamic Psychotherapy

28.2 Brief Psychodynamic Psychotherapy

The growth of psychotherapy in general and of dynamic psychotherapies derived from the psychoanalytic framework in particular represents a landmark achievement in the history of psychiatry. Brief psychodynamic psychotherapy has gained widespread popularity, partly because of the great pressure on health care professionals to contain treatment costs. It is also easier to evaluate treatment efficacy by comparing groups of persons who have had short-term therapy for mental illness with control groups than it is to measure the results of long-term psychotherapy. Thus, short-term therapies have been the subject of much research, especially on outcome measures, which have found them to be effective. Other short-term methods include interpersonal therapy (discussed in Section 28.10) and cognitive-behavioral therapy (discussed in Section 28.7).

Brief psychodynamic psychotherapy is a time-limited treatment (10 to 12 sessions) that is based on psychoanalysis and psychodynamic theory. It is used to help persons with depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder, among others. There are several methods, each having its own treatment technique and specific criteria for selecting patients; however, they are more similar than different.

In 1946, Franz Alexander and Thomas French identified the basic characteristics of brief psychodynamic psychotherapy. They described a therapeutic experience designed to put patients at ease, to manipulate the transference, and to use trial interpretations flexibly. Alexander and French conceived psychotherapy as a corrective emotional experience capable of repairing traumatic events of the past and convincing patients that new ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving are possible. At about the same time, Eric Lindemann established a consultation service at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston for persons experiencing a crisis. He developed new treatment methods to deal with these situations and eventually applied these techniques to persons who were not in crisis, but who were experiencing various kinds of emotional distress. Since then, the field has been influenced by many workers such as David Malan in England, Peter Sifneos in the United States, and Habib Davanloo in Canada.

TYPES

Brief Focal Psychotherapy (Tavistock–Malan)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree