Psychotherapy with couples

Michael Crowe

Introduction and background

There is an ongoing crisis in the institution of marriage, at least in Western cultures. There has for some time been a tendency to idealize marriage, and at the same time social forces are operating which tend to undermine it.(1) These influences have probably made a contribution to the increasing divorce rate, as well as the tendency for fewer couples to marry, and have probably also led to an increase in the number of couples seeking help with their relationships.

In the United Kingdom, for example, the number of marriages taking place each year has fallen for the first time in living memory, and the number of divorces is still steadily increasing, reaching 40 per cent of marriages in 1996.(2) There are also a large number of ‘common-law’ marriages, often with children, as well as more transient cohabiting or non-cohabiting sexual relationships, both heterosexual and homosexual. The stability of these relationships is, of course, not recorded in the marriage or divorce statistics, and the rate of breakup can only be guessed at; however, it is very probable from clinical experience that in these non-marital relationships there is a higher than 40 per cent incidence of breakup. In the wake of these changes, there are a large number of

single-parent families and ‘reconstituted’ or blended families, as reviewed by Robinson,(3) and there is a decreasing proportion of children who are being brought up in the traditional nuclear family with two biological parents.

single-parent families and ‘reconstituted’ or blended families, as reviewed by Robinson,(3) and there is a decreasing proportion of children who are being brought up in the traditional nuclear family with two biological parents.

In addition to these new factors affecting marriage in the early 21st century we should also be aware of the fact that many countries, especially those in the developed world, have a multicultural society, and that immigrant cultures have different attitudes to marriage and family life. For example, families from the Indian subcontinent often prefer to arrange marriages for their children, and in some cases insist that the couple live in the husband’s parents’ house. On the other hand, West African couples often leave their children in Africa to be looked after by family members for long periods of time, while the parents work or study in the West.

In the last few years, Gay marriage or Civil Partnership has been recognized in many western countries. Couples in Gay relationships have many of the same problems and satisfactions as heterosexual couples, and in addition, must live with fairly widespread negative attitudes and homophobia from neighbours, family and society generally. Their relationships have to be, if anything, stronger than heterosexual ones to survive these pressures, and may be more in need of therapy.

Couple therapy must be able to take account of these factors, and whilst much of what is contained in this chapter will relate to heterosexual married British couples living with their biological children, it should be understood that there are many other types of relationship which can be helped using a similar approach, with appropriate changes of emphasis. In a later section, there will be some additional discussion of the specific problems relating to couples from other cultures, and ways of managing these.

Couple counselling and couple therapy

The concept of couple counselling dates from the 1920s when in the United States the American Association for Marital Counselling was formed; in the United Kingdom the Marriage Guidance Council (now called Relate) was founded in 1938. Counselling mainly took the form of giving advice on practical issues, but in more recent years, Relate counselling has been orientated more towards psychodynamic approaches, and favours a longer-term involvement with the couple. Couple counselling continues in both countries, and the great majority of couples seeking help with their relationships are seen by couple counsellors, rather than any other types of therapist.

The distinction between couple counselling and couple therapy is not an easy one, because many of the interventions are similar. In a simplistic sense therapy attempts to make a more radical difference to the couple’s functioning than counselling, which has the general aim of improving adjustment to the situation as it is. However, many forms of both couple therapy and couple counselling are based on a theoretical formulation which is derived from a related school of individual psychotherapy (for example, cognitive behavioural or psychodynamic). Thus, theoretical formulations in the resultant couple work are so different between therapies (e.g. psychodynamic as against behavioural) that a particular form of counselling may have more in common with a related form of couple therapy than that therapy itself has with another type of couple therapy.

Psychoanalytic/psychodynamic couple therapy

Couple therapy using a psychodynamic model began in the United Kingdom in 1948, when Dicks and his colleagues founded the Institute of Marital Studies. The theories and techniques involved have been ably reviewed by Daniell(4) and Clulow.(5) The central concept used is that the inner (unconscious) world of the two partners determines their interaction and their response to changing circumstances. It is as though each partner has an internal blueprint, both of themselves and each other, formed partly by observation but also partly by the influence of earlier intimate attachment experiences with parents, siblings, or friends. These influences may actually determine the choice of partner, and the nature of each partner’s patterns of attachment (secure or insecure) will affect the ways in which they cope with the stresses of the new relationship. There may then be projections which lead one partner to attribute motives such as hostility or sadism to the other, whereas in fact this is a split-off and denied characteristic of the first partner. Other consequences of this unconscious process may include the system of shared fantasies and defences which builds up as the relationship continues.

In therapy, four premises are used, which inform a relatively long-term and open-ended series of sessions. The first is that a person’s emotional health is related to his or her capacity to manage both internal conflict and external stress: it is important to be able to experience fear as well as trust, pain as well as pleasure, doubt as well as certainty, frustration as well as satisfaction. Secondly, significant relationships can be used to resurrect, but also change, inflexible patterns of behaviour established in the past. Thirdly, unconscious processes need to be taken into account when attempting to understand problems in relationships. Fourthly, change takes time because it requires a reordering of perceptions of self and others, perhaps with the help of transference interpretations by the therapist involving both partners.

Therapy in this mode may be carried out by one therapist seeing both partners, but is more often done by two therapists either seeing the couple together or in parallel individual sessions, using one partner with one therapist, with joint supervision of the two therapists. An intriguing aspect of this therapeutic format is that sometimes the two cotherapists find themselves interacting in unfamiliar ways, in sessions and between sessions, which are thought to represent the projection of fantasies and feelings by the couple on to the therapists; the therapists’ understanding of these projections in their joint supervision may play a role in advancing the therapy itself. If these insights are used to inform the therapists’ interaction with the couple, the individual partners may then be made aware of their own conflicts, fantasies, and projections, and thus be able to give up some of their repetitive patterns of behaviour and withdraw damaging projections.

The psychoanalytic approach has been an important source of theoretical ideas in couple therapy, especially the concepts of attachment and loss developed by Bowlby.(6) It has also the distinction of being the first theory to be adapted to this area of work. There are, however, some drawbacks to working in this way, as enumerated by Wile.(7) He sees the emphasis on negative impulses and emotions (e.g. dependence, narcissism, sadism, manipulation, and exploitation) as painting a rather unflattering and negative picture of the couple in therapy, and perhaps therefore reducing

their motivation to continue. A more serious problem with the approach is that the psychodynamic concepts, whether of defence mechanisms, projections, or shared fantasies, are treated as if they were as real as observed behaviour, whereas in fact they must remain assumptions based on hypothetical constructs, and are really only valuable in so far as the therapy based on them is effective.(1)

their motivation to continue. A more serious problem with the approach is that the psychodynamic concepts, whether of defence mechanisms, projections, or shared fantasies, are treated as if they were as real as observed behaviour, whereas in fact they must remain assumptions based on hypothetical constructs, and are really only valuable in so far as the therapy based on them is effective.(1)

The question of efficacy is raised later in the chapter, but it must be stated here that the psychodynamic therapies for couple problems have only seldom been submitted to controlled trial, and then usually in a relatively short-term form. The therapy may be quite long term, and the improvements seen are usually not dramatic, so that in the last analysis the approach has to remain of uncertain value.

Behavioural couple therapy

The behavioural approach, in contrast, makes no assumptions about internal conflicts or underlying mechanisms in the individuals. The approach was initiated in 1969 by Stuart(8) and Liberman(9) as behavioural marital therapy. They worked from the principles of operant conditioning and made the assumption that couples who were having difficulties were either giving each other very low levels of positive reinforcement or were using punishment or negative reinforcement to coerce each other into behaving differently. The remedy that they proposed for this situation was to help the partners to learn how to persuade each other to conform to the desired pattern of behaviour by the use of prompting and positive reinforcement. Thus, complaints would be transformed into requests and requests into tasks agreed by both partners.

Behavioural marital therapy relies on the therapist’s observation of the couple’s behaviour in the session and on the problems they report from the previous week or equivalent timespan. There are two types of therapeutic activity in behavioural marital therapy. The first is reciprocity negotiation, in which the partners request changes in behaviour on each side and negotiate how this can be achieved through mutually agreed tasks. The second is communication training, in which the partners are encouraged to speak directly and unambiguously to each other about feelings, plans, or perceptions, and to feed back what they have heard and understood. In both these approaches, the deeper meanings behind a particular piece of behaviour are ignored, the emphasis being on change in the interaction both in the here and now and in the immediate future. The approach has been the subject of many controlled trials (see below), and is of proven efficacy.

Cognitive behavioural and rational-emotive couple therapy

Aaron Beck,(10) in his cognitive behavioural approach to couple therapy, identifies in the communication of disturbed couples many of the problems found in the thinking of depressed patients, and attempts to correct these. Thus, he tackles misunderstandings, generalizations, untested assumptions, and automatic negative thoughts by challenging assumptions, reducing unrealistic expectations, relaxing absolute rules, improving the clarity of the communication and focusing on the positive rather than the negative.

Similarly, Albert Ellis (reviewed by Dryden(11)) uses a rational-emotive approach to couple problems. Here, the main focus is on the use of words; terms such as ‘intolerable’ are replaced by (for example) ‘difficult to accept’, and the couple are encouraged to express desires rather than demands. There is an analysis of the repetitive cycles of cognitive and behavioural disturbance, in which each partner may attribute the other’s behaviour to a negative motive and assume that nothing can be done about it. The general thrust of this therapy is similar to that of Beck, but with a more lively and less formalized approach in the session.

Systems therapy for couple problems

The systems approach to couple therapy derives partly from concepts developed by Minuchin(12) and Haley,(13) and partly from the work of Selvini Palazzoli et al.(14) All these pioneers worked predominantly with families rather than couples, but many of their ideas and techniques are relevant to the treatment of couples. Although the systems approach to therapy has broadened and deepened since the 1980s, many of the early concepts are still very useful.

A central concept in thinking about couple relationships is ‘enmeshment’, by which is meant an excessive involvement in what is essentially the private business of another person. It is quite common to find an enmeshed relationship between parents and their teenage children, in which both sides find it very hard to ‘let go’. It can also be found in couple relationships where one partner wants to be closer than the other, and a conflict arises as to what is the best distance to maintain. Systems therapy aims to help them to find a compromise ‘distance’ which suits them both, and thereby to reinforce the necessary ‘boundaries’ which people need in maintaining their individuality within a relationship.

The concept of circular causality is also central to systems work. This enables the couple to get away from the idea that one person is necessarily to blame for a particular situation by considering the continuous cycle of cause and effect in which A’s actions may be caused by B’s actions and also B’s may equally be caused by A’s. Thus, systems therapists, when approaching a couple problem, do not focus on one partner’s behaviour, but rather on the pattern of interaction obtaining in the relationship. They will then try to effect a change in which both partners contribute actively to the solution of the problem.

Systems therapists have many techniques at their disposal, including those which increase the couple’s understanding of the system they are participating in. These include family genograms (a form of family tree construction which leads to discussion of transgenerational influences or ‘systems over time’), family ‘sculpting’ (in which the members position themselves and each other wordlessly to represent their current relationships), and the discussion of ‘family myths’ and stories. More active techniques, designed to play a part in changing the family interaction, include creating conflict in the session, giving homework tasks, and the use of ‘paradoxical injunctions’ in which the therapist tells the family to continue with the current interaction because, even though it is problematic, it seems to be protecting them from worse consequences. These more active techniques will be dealt with in more detail in the main part of this chapter on behavioural-systems therapy.

Mixed or eclectic approaches

Most couple therapists use a mixture of techniques, and it seems that this is probably an inevitable consequence of the difficulties

involved in applying one therapeutic method rigorously in a clinical setting. A number of specific combinations have been advocated, and will be briefly mentioned here.

involved in applying one therapeutic method rigorously in a clinical setting. A number of specific combinations have been advocated, and will be briefly mentioned here.

The first is the psychodynamic-behavioural approach of Segraves.(15) In this, the basic underlying cause of marital disturbance is assumed to be the partners’ conflicting internal and unconscious projections, and their interactions. The therapy, however, is not only directed at helping them to understand these (as in psychodynamic therapy) but also to increase their negotiating and communicating skills (as in behavioural marital therapy).

The second is a more comprehensive mixture of theory and technique, known as the intersystem model, and advocated by Weeks.(16) This tries to take account of the individual, interactional, and intergenerational aspects of couple relationships, and combines them in what is probably closest to a systems model, but with more emphasis on the psyche of the individual. Interventions are on both a conjoint and individual basis, and the techniques of decentring (see below) and paradoxical injunctions are often used.

The third eclectic approach is that of Spinks and Birchler.(17) This is called behavioural-systems marital therapy, and makes use of behavioural marital therapy as the main form of intervention, moving into the systems mode when ‘resistance’ emerges. There are many similarities between this form of treatment and the one described in the main part of this chapter, but our ‘behavioural-systems approach’ is more integrated as between the two components of the method.

The fourth eclectic approach which should be mentioned is that of Berg-Cross.(18) She uses rational-emotive, sociocognitive, systemic, psychodynamic, humanistic, and theological concepts to understand and modify couple relationships. Like that of Weeks, her approach gives the therapist a very wide canvas to work on, but may lose some of the focus by being very general and all-embracing.

The behavioural-systems approach to couple therapy

Behavioural-systems couple therapy is the approach that will be described in detail in the present chapter, and although it is only one of several approaches to couple problems, it has the advantage of spanning two of them, and issues such as indications for therapy and assessment are shared with both the pure behavioural and systemic approaches. It is the method developed at the Maudsley Hospital Couple Therapy Clinic in the 1980s. It has been expounded at greater length by Crowe and Ridley,(1) and like some of the other eclectic models mentioned above it combines two different approaches, behavioural marital therapy and systems family therapy. The behavioural dimension, similarly to that described by Stuart (8) and Jacobson and Margolin,(19) consists of the relatively straightforward methods of reciprocity negotiation and communication training. The systems dimension is more complicated, and involves systems thinking, structural moves during the session, tasks and timetables for the couple between sessions, and the use of paradox. The method was developed in a predominantly psychiatric setting, and has been found to be particularly suitable for those couples where one or both partners has psychiatric problems in addition to their relationship difficulties. It is also useful as an adjunct to psychosexual therapy where a sexual dysfunction or a sexual motivation problem seems to be connected with relationship issues.

The method should be thought of as a series of menus from which the practitioner can choose techniques rather than as a set course of therapy beginning at one point and ending at another. Thus, the various components of behavioural-systems couple therapy can be incorporated at any time in the therapy session, although in practice, negotiation, communication training, and structural moves are usually employed in the earlier part of the session, while tasks, timetables, and paradox are usually reserved for the ‘message’ at the end, and are linked to homework assignments to be carried out between sessions.

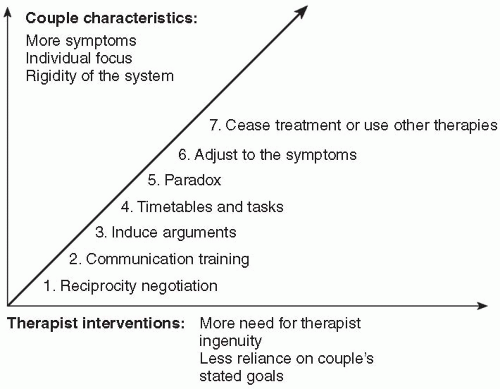

The different techniques of behavioural-systems couple therapy can be thought of as belonging to a kind of hierarchy. The so-called ‘hierarchy of alternative levels of intervention (ALI)’(1) links each type of intervention with a particular set of clinical problems and makes recommendations as to the type of intervention that is appropriate. The ALI hierarchy is shown in diagrammatic form in Fig. 6.3.7.1. As may be seen, where the couple appear to have greater rigidity in their behaviour, where they show more symptoms, and where they show more reluctance to accept the relationship as the focus of work, the therapist needs to move to the systems end of the hierarchy, and use more ingenuity in the development of interventions. If, however, the couple accept the interactional focus and show willingness to recognize the part that the relationship is playing in maintaining the problems, the therapist may be quite comfortable and effective working behaviourally. By and large, the preference is to work behaviourally, since this implies collaborating with the couple and accepting their stated goals, whereas the systems approach puts the therapist into a more managing role, deciding what is best for the couple and suggesting tasks that may not be what they would expect. It should be emphasized that the therapist may at any stage move up or down the hierarchy, according to the couple’s response: an increase in flexibility shown by the couple could be the trigger for the therapist to begin working in a more behavioural way, whereas an increase in rigidity or a failure to respond to behavioural work could be met by a more systemic approach.

Indications and contraindications

If there is a relationship problem identified by either the couple or their advisers, even if there are also individual psychiatric or behavioural problems, and if the couple are willing to attend together, then in most cases they are suitable for behavioural-systems couple therapy. The breadth of the therapeutic approach, the fact that the behavioural techniques are of proven efficacy (see below), and the fact that the systemic interventions are suitable for those with more psychiatric symptoms or similar problem behaviours, all give the therapy a wide range of positive indications.

(a) The nature of the problem

Clearly those with relationship problems such as arguments and tensions are highly suitable for couple therapy. Another related indication is those relationships in which one partner (who might be attending a counsellor or psychiatrist alone) spends much time complaining about the absent partner’s behaviour. A third indication is where the health of one partner suffers following the other partner’s individual therapy.

Many problems with sexual function would be suitable for couple therapy, including those couples where there is a disparity in sexual desire, or those where one partner has a specific phobia for sex. In some such cases there is also a need for individual therapy, especially where one partner is the survivor of earlier childhood sexual abuse.

Many people with depression or anxiety, especially those where there is also poor self-esteem, may be suitable for couple therapy. There are often aspects of the illness that are exacerbated by problems in the relationship. Indeed, in a study by Leff et al. in 2000(20) it was shown that couple therapy was an effective and acceptable form of treatment for couples in whom one partner was depressed.

Where jealousy is present the problem usually affects the nonjealous partner to a greater or lesser extent, and here it would almost always be useful to have at least a few conjoint sessions with the couple, as suggested by De Silva.(21)

Some problems are perhaps less amenable to couple work, and among these are, for example, phobias which seem unconnected with home life in any way, and post-traumatic stress reactions where the event happened away from the partner. Some alcoholic and drug-addicted patients have so much of their existence involved with the addiction that they are not available emotionally to do couple work, and the work would at that stage be wasted on them. Similarly, those with an acute psychosis would, at the time they are acutely ill, be unavailable to this kind of therapy, and should not be offered it. However, in both cases, when the acute crisis is over and the addiction or psychosis is under control, it would be very appropriate to offer them some kind of couple therapy, even if this had limited aims and expectations. Some of the most useful psychological interventions in schizophrenia, after the acute illness has resolved, involve the nearest relative, as shown by McFarlane.(22)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree