Psychosis is a state of disordered thoughts or impairment in reality testing, as manifested by perceptual disturbances (e.g., hallucination) and disorganized speech and behavior.

Secondary psychotic disorders can be caused by general medical conditions (e.g., dementia or delirium with psychosis), side effects from prescribed medications (e.g., prednisone or potent opioid analgesics), severe mood disorders with psychotic features such as depression and bipolar disorder, and illicit substance use.

Positive psychotic symptoms are outward manifestations of the thought disorder: hallucinations, delusions, and bizarre or disorganized behaviors or speech. Negative psychotic symptoms include affective flattening (decreased expressed emotions), alogia (poverty of thoughts), attention deficits, anhedonia, amotivation, and social withdrawal.

The American Psychiatric Association recommends indefinite antipsychotic medication treatment against recurring psychosis in patients with primary psychotic disorders, if two or more episodes occur within 5 years.

Treatment of chronic psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia, begins with the selection of an appropriate second-generation antipsychotic (SGA) medication and referral for psychosocial services.

Patients who have schizophrenia are at an increased risk for developing metabolic abnormalities. The addition of any SGA carries an additional risk for weight gain, dyslipidemia, and glucose dysregulation. In addition to obtaining the weight and waist circumference at each visit for all patients who are on an SGA, a fasting glucose must be checked before the SGA is started, at week 12 after it was started, and annually thereafter. A fasting lipid panel should also be monitored before the SGA is started, 12 weeks into treatment, and every 3 to 5 years thereafter.

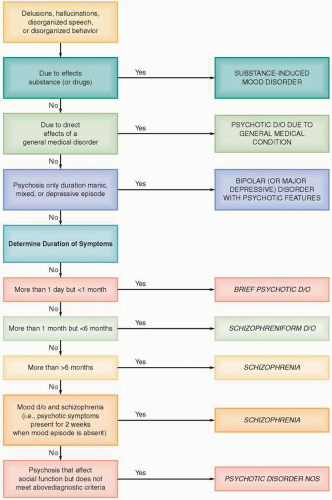

there are seven defined disorders: schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, brief psychotic disorder, delusional disorder, shared psychotic disorder, and psychotic disorder not otherwise specified (3). Secondary psychotic disorders are clinical conditions in which psychosis is a complicating symptom of a general medical condition or a medication (e.g., encephalitis or the use of high-dose steroids), substance use disorders (e.g., amphetamine- or cocaine-induced psychosis), or mood disorders (e.g., major depression with psychotic features). Patients with relapsing and remitting psychosis usually have a chronic psychotic disorder, representing a primary psychotic disorder. In these cases, symptoms have a high likelihood of recurrence. Patients with untreated psychotic disorders have associated cognitive dysfunction that results in disability, including the inability to work, poor social functioning, poor hygiene, malnutrition, and early death (4). The seven primary psychotic disorders are discussed below.

Table 5.1 Diagnostic Criteria for Schizophrenia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

disorder carries a poor long-term prognosis that is similar to or worse than schizophrenia.

process of patients who present with psychotic symptoms using the PSΨCHOSIS mnemonic.

Table 5.2 Assessment of Patients with Psychotic Symptoms: PSYCHOSIS Mnemonic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

symptoms. Often, empathizing with the level of distress can be done without challenging or confirming the symptoms. For example, one might say, “It must be frightening and frustrating to believe your coworkers are monitoring your every move while at work and home.” Collateral information sources should be obtained to supplement the subjective history whenever possible.

Table 5.3 Definition of Psychotic Symptoms | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Patients with delirium frequently have impaired levels of consciousness, such as disorientation and impaired ability to sustain attention. Dementia should be considered as a causative factor for psychotic symptoms as about 30% of patients with dementia have comorbid psychosis. Table 5.5 helps to distinguish between delirium, dementia, and primary psychosis.

Table 5.4 General Medical Causes of Psychosis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree