, Jeffrey R. Strawn2 and Ernest V. Pedapati3

(1)

Division of Psychiatry and Child Psychiatry, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA

(2)

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA

(3)

Division of Psychiatry and Child Psychiatry Division of Child Neurology, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA

Such is the wonder of the human condition; the emergence of new ways of being together and new meaning in relation to the world and to one’s self.

—Ed Tronick and Marjorie Beeghly

The modern child and adolescent psychiatrist is well trained, familiar, and comfortable with the use of the structured DSM–5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition, APA 2013) interview style. In some contexts, an even more structured interview may be desired, and several well-validated tools are available to achieve this, including the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID) and the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Aged Children: Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL ), which have both been demonstrated to have high levels of interrater and test–retest reliability (Sheehan et al. 2010; Kaufman et al. 1997). Thus, our assertion is not that these methods are invalid or unreliable; rather, they are somewhat limited when seen within the context of a contemporary two-person relational psychology model in understanding human behavior and psychopathology.

In our experience, the well-worn biopsychosocial model of diagnostic formulation is an uneasy trinity of disparate disciplines (Engel 1980). As commonly practiced, each of these domains is derived from a different historical origin and maintains its own set of beliefs. Given these inherent differences, the limited capacity for true integration becomes apparent. However, by substituting the traditional one-person model with the contemporary two-person relational approach, we have fundamentally transformed the biopsychosocial model by bringing harmony within its ranks. Considering that two-person relational psychology was developed over the last century hand in hand with advancements in the fields of genetics, attachment theory , developmental research, neuroscience, and social and cognitive sciences, it is natural that the standard diagnostic interview needed to be revised into a more flexible and comprehensive approach.

We have structured this chapter with the goal of helping the child and adolescent psychiatrist in training, the newly minted, or the experienced clinician learn how to use the two-person relational contemporary diagnostic interview model. This interview model provides an integrated developmental approach (biopsychosocial) in understanding children or adolescents, which can help develop realistic and practical treatment recommendations. The integrated interview is intended to be helpful in any setting and not limited to the evaluation of a child’s or adolescent’s readiness for psychotherapy.

8.1 Contrast of the Contemporary Diagnostic Interview (CDI) to a Traditional Diagnostic Interview

The goal of any diagnostic interview is to help the child and adolescent psychiatrist or trainee tailor the treatment approaches that best suit the patient and ideally take a biological, psychological, and social integrated approach (McConville and Delgado 2006).

The child and adolescent psychiatrist traditionally asks the child, adolescent, and/or their parents to share the history of their present illness, with a timeline that establishes when they first noticed the symptoms, the frequency of symptoms, and variations in the intensity of symptoms over time, along with precipitating and perpetuating factors. Over the course of a traditional psychiatric evaluation, the child and adolescent psychiatrist or clinician may quickly become focused on elucidating risk factors, identifying predictors of treatment response, and determining which “symptoms ” meet threshold criteria for a disorder. Thus, with the standard use of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition ( DSM–5, APA 2013), the diagnosis is based on a collection of signs and symptoms that have been well defined. The child and adolescent psychiatrist or clinician is charged with incorporating the information obtained from the patient, his or her family, and also other multiple sources (e.g., prior medical or psychiatric treatment records) into the formulation of effective recommendations, whether psychotherapeutic or psychopharmacological.

It is agreed that an integrated biological, psychological, and social interview is valuable when assessing patients and developing well-thought-out treatment plans (Delgado and Strawn 2014). However, it is generally agreed that child and adolescent psychiatrists in training learn to switch interview and diagnostic approaches rather than integrate them, as Cardoso Zoppe et al. (2009) state, “There is still tension between biological and psychosocial tendencies.” They further highlight that current teaching methods for trainees routinely lack integration and are heavily influenced by the setting in which the patient is seen (e.g., academic, local hospital, community mental health center) and their supervisors’ school of thought (e.g., traditional one-person, psychopharmacologist, behaviorist).

A 12-year-old male with poorly controlled bipolar disorder

A 12-year-old male with poorly controlled bipolar disorder has been increasingly agitated at home and at school. In supervision, it is suggested that the child and adolescent psychiatrist trainee consider increasing the dose of the patient’s mood stabilizer. A few months later, in the same setting but with a two-person relationally informed supervisor, the trainee shares that the child has continued to respond poorly to the medication changes. Though a combination of two mood-stabilizing agents intended to treat a rapid-cycling bipolar disorder was considered, the supervisor considers an alternative diagnostic formulation. The possibility within the integrative model is that the child may have cognitive weaknesses, which could explain his poor abilities for behavioral self-regulation when asked to complete complex tasks (e.g., schoolwork, homework, and chores); medications had been of limited value in these contexts. The supervisor asks if the trainee had inquired about whether the troubling behaviors were also reported when the child was involved in simple tasks, such as games with family and peers, or when engaged in sports. In fact, there were differences, although the trainee had thought they were due to the ebb and flow of a mood disorder and not suggestive of temperamental and cognitive problems. Furthermore, the trainee shares that the patient had a psychotherapist who described the child as difficult with a poor moral compass and who asked the trainee to consider changing medications as the current “are not working.” In short, the trainee and psychotherapist had not taken an integrated developmental approach in their diagnostic formulation of the child.

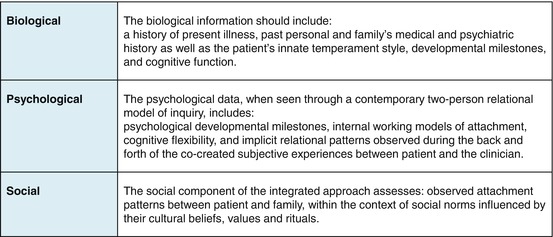

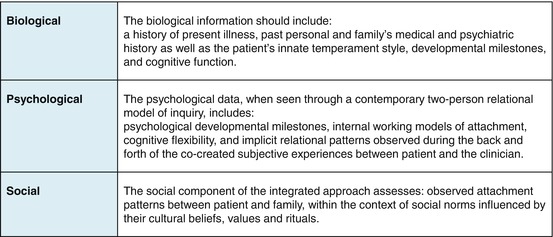

From a biopsychosocial perspective, we propose that when an integrated developmental approach is used in developing a comprehensive diagnostic formulation , as in the case of the 12-year-old boy described above, it facilitates the complex decision making needed to outline the sequencing of the interventions to ensure successful outcomes. One might describe this approach as a grasp of the interplay between the forces of nature and nurture (Table 8.1).

Table 8.1

The biopsychosocial model

We are aware that the skeptic child and adolescent psychiatrist trainee would ask whether a biopsychosocial developmental interview is useful or practical. Further, some feel that the child and adolescent psychiatrist should practice at the top of their license: the evaluation of a psychiatric DSM–5 diagnosis with pharmacological recommendations and a referral to an allied professional for psychosocial interventions if considered appropriate (Drell 2007). The authors are frequently asked, “Isn’t a detailed biopsychosocial evaluation needed only if we are going to recommend individual or family therapy?” This could not be farther from the truth, when considering that an integrated approach provides the critical information needed in designing treatment recommendations and gives insight about whether the patient and family is likely to comply.

In using a traditional DSM–5 type of interview, generally the child and adolescent psychiatrist’s diagnostic formulation is based on the assumption that the responses by the patient and parents or caregivers are factual and accurate, unless due to psychotic processes or developmental disabilities . Delgado and Strawn (2014) aptly capture the limitations of the DSM–5-style interview in child and adolescent psychiatry, namely, that it ignores the patient’s temperament, internal working models of attachment , learning abilities or weaknesses, and cognitive flexibilities within the backdrop of the family and of the social and cultural environment in which they have lived. Herein, the careful assessment of the patient’s innate and relational factors allows the child and adolescent psychiatrist or clinician to obtain in a succinct manner critical information as to whether the responses provided are actually factual and accurate and then use this information to tailor an effective treatment regimen (Delgado and Strawn 2014).

A 12-year-old male with poorly controlled bipolar disorder (continued)

As we continue the case of the 12-year-old child with bipolar disorder, the agitation and behavioral problems were seemingly due to temperamental difficulties, insecure attachment style, and learning disabilities that contributed to poor cognitive flexibility and suggest why medications were changed often and with limited results. In knowing this, the trainee can begin to sequence the interventions: This is done by requesting formal cognitive testing, beginning wraparound in-home services, developing visual behavioral strategies at school, and educating the family and teachers about having realistic expectations for the child.

Although attending to temperament , internal working models of attachment, learning abilities or weaknesses, and cognitive flexibilities may initially seem like a daunting task for the child and adolescent psychiatrist or clinician, it avoids polypharmacy and reduces the likelihood of serious side effects. We are not minimizing the lifesaving experiences some children and adolescents can have with the appropriate use of medication; rather, we are cautioning about the tension between biological and psychosocial interventions that can be limiting to a child’s future (Kaplan and Delgado 2006).

8.2 Overview of the Contemporary Diagnostic Interview (CDI)

Although we have identified some of the weaknesses of the traditional DSM–5 structured interview model, our primary goal is to add and enhance the techniques available to the child and adolescent psychiatrist or clinician’s toolbox to improve the diagnostic reliability needed. However, we would not expect many of the “tools” to initially fit neatly into current clinical practice. The contemporary diagnostic interview (CDI) is aimed at observing and interacting with patients and their parents or caregivers, and it is designed to capture a different spectrum of information that is inaccessible by the standard DSM–5-style interview. As with the adoption of any new useful and practical technique, the initial challenge will be overcome through careful study and frequent practice.

We have found that the CDI increases reliability, consistency, and accuracy in the description of the signs and symptoms endorsed by children and their parents or caregivers, allowing for the development of a comprehensive diagnostic formulation , as well as a two-person relational psychodynamic formulation. Herein, we will outline a “how to” guide to complete a detailed CDI for the reader to consider using in his or her day-to-day clinical work.

In certain medical situations such as a stroke or a dangerous arrhythmia, we would argue that all the evidence needed for an accurate diagnosis and assessment are plainly visible. However, we would argue that neuroscience has demonstrated that human behavior does not readily play by the same rules of the observable to the plain eye. Human behavior is exquisitely contextual and is influenced by numerous factors, including both internal and external cues. Thus, a traditional unilateral approach may, despite the best intentions of the clinician, result in obscuring the true nature of the psychological difficulties and thus prevent optimal treatment. In contrast, we suggest that engaging in the complex process of understanding our patients and their parents or associated caregivers requires the active participation by the child and adolescent psychiatrist or clinician to create an atmosphere of safety, curiosity, and exploratory inquiry of all participants’ subjective experiences, which will result in a more accurate representation of the patient’s lifestyle and concerns at hand.

To illustrate this point, we consider our colleagues in pediatric cardiology . The astute reader may claim that any form of a psychiatric diagnostic interview is not different than a pediatric cardiology evaluation, as they are both based on a collection of signs and symptoms that have been well defined. In fact, child and adolescent psychiatrists, like pediatric cardiologists, have begun to use neurological diagnostic tests, computerized testing, and laboratory tests with increasing frequency. We propose that the difference lies in the moment in which the pediatric cardiologist intently listens to the quiet perturbations of the heart with his stethoscope on the chest of the young patient. In these few seconds, the pediatric cardiologist integrates his or her own subjective sense of what the young patient needs to feel safe as the pediatric cardiologist reaches for the patient’s chest with exquisite sensitivity to the patient’s unique physiology, quietly responding to what he or she hears and rapidly adjusting his or her attention and exam based on this moment of cocreation. The pediatric cardiologist’s future actions are tempered by the observable and the implicit feedback provided by the young patient in the here-and-now moments during the examination. Here, we must stress that this is not a “mystical” moment but rather one informed through the unique clinical intuition about working with children that was acquired during the cardiologist’s early childhood experiences as implicit relational patterns stored in his or her implicit nondeclarative memory systems and also through his or her subsequent rigorous training grounded in an in-depth understanding of anatomy and physiology. Herein, in a recent study, pediatric cardiologists could identify a pathologic heart condition using only their physical exam nearly 92 % of the time (Mackie et al. 2009) even when they did not have access to an electrocardiogram (routinely performed at most visits). Thus, there is both an explicit and implicit comparison between the pediatric cardiologist’s and the child and adolescent psychiatrist’s exam. The moments during the time a stethoscope is on the chest, the awareness and interpretation of these “moments of meeting” (Chap. 5) shared by both parties are critical to any subsequent decision making. The child’s experience in the situation will influence their heart rate and their willingness to cooperate. Scientific advancements have broadened our understanding of the importance of nonverbal communication and implicit nondeclarative memory when people interact with each other. For the pediatric cardiologist, the lines are blurred between a verbal history and the telltale physical signs; both stories are provided by the young patient yet neither is sufficient. We hope to demonstrate through the findings of modern developmental research and neurosciences that the tried-and-true semistructured verbal interview is only a narrow slice of the raw spectrum of data available to the child and adolescent psychiatrist.

The Contemporary Diagnostic Interview

The clinician provides an atmosphere of safety

Approaching the patient and parents or caregivers with vitality

The alliance: goodness of fit for mutual curiosity

The clinician has an open frame of mind

The Four Pillars of the Contemporary Diagnostic Interview

Temperament

Cognition

Cognitive flexibility

Internal working models of attachment (IWMA)

Putting It All Together: Diagnostic Formulation and Treatment Plan

Two-person relational psychodynamic psychotherapy

Cognitive and behavioral therapies

Criteria for formal cognitive testing

Criteria for pharmacological intervention

8.3 The Contemporary Diagnostic Interview

The goal of a contemporary diagnostic interview is to facilitate the expression of the patient’s and his or her parent’s temperament, cognition, cognitive flexibility, and the patterns of relating with each other and with others. The child and adolescent psychiatrist’s or clinician’s initial approach is best received when all parties are included in the interview. This allows for an initial in vivo subjective experience of how the patient and family have “danced together.” This is heightened by the fact that a request for a psychiatric evaluation of a family member places the system in a stressful situation.

The advancements in developmental research and neuroscience inform us that many more people are implicitly present during the encounter than what appears. In addition to the personality attributes of the child and/or adolescent and his or her family, the child and adolescent psychiatrist also brings, through his personality, his or her own set of early childhood implicit relational experiences. Thus, given our understanding of internal working models of attachment, the interview room is actually crammed by nonconscious neurological imprints of past and present from each individual.

We will now describe how the child and adolescent psychiatry trainees and experienced clinicians alike can effectively perform a contemporary diagnostic interview (CDI). Thus, to effectively perform a CDI, the child and adolescent psychiatrist or clinician will need to do the following simultaneously: (1) provide an atmosphere of safety in which the patient and his or her parents realize that they are more than a set of signs and symptoms to be fixed; (2) approach the patient and parents and/or caregivers with vitality ; (3) provide a genuine emotional alliance that allows for mutual curiosity about each other’s subjectivities, including temperament, cognition, cognitive flexibility, and internal working models of attachment (IWMA) from childhood experiences; and (4) begin the interview with an open frame of mind that allows for the psychiatrist or clinician to respond intersubjectively and in a meaningful way to the patient’s and his or her family’s subjectivities. As Buirski and Haglund say, “There is no subjectivity without intersubjectivity ” (2009).

The Clinician Provides an Atmosphere of Safety

Patients and families approach mental health appointments with a great deal of trepidation and anxiety. Without an effort to create an atmosphere of safety to reduce their implicit anxiety, the information obtained will be filtered through their lens of caution and thus will be partially true but not complete. We can implicitly help patients and families feel safe if they subjectively experience that the psychiatrist or clinician is considering them as a system that has lived together for many years rather than as persons with symptoms. With practice, the clinician can initiate a conversation with friendly and jovial joining comments about external attributes of the patient and parents or caregivers to create an experience for them in which they feel important as persons and not simply entities with signs and symptoms.

Approaching the Patient and Parents or Caregivers with Vitality

In our experience, approaching the patient and their parents or caregivers with vitality as part of a CDI provides the child and adolescent psychiatrist or clinician the opportunity to engage with an openness and willingness to be known as a person that is interested in who the patient and their parents or caregivers are as both people and members of a larger unit. There is one teaching metaphor that resonates across demographics and captures the core principles of the CDI vitality: approaching the patient and parents or caregivers as a young family member. We propose that the contemporary approach to a patient and their parents or caregivers should be similar to that of approaching a young family member (e.g., cousin, niece, or nephew).

When adult family members meet a young family member, and it occurs as a welcoming and desirable moment (albeit with some anxiety), secure internal working models of attachment implicitly create a space of vitality that allows the young child and parents to “figure out” how to successfully and emotionally attune to each other. The adult family member’s active sense of curiosity allows the young child, in the nonverbal realm, to search for social reciprocity and affective attunement with the adults, which then become coded and stored in nondeclarative memory (Chap. 5). The loving family members first learn to be like them (the young child) by synchronizing their gaze and with rhythmicity matching the voice and body movements of the young child. This facilitates the process of the young child recognizing the adult family member as like me (the young child). Both sides can then begin to store each other’s state of mind in nondeclarative memory (Meltzoff 2007, see Attending to the external attributes of the patient, this chapter).

In using this as a metaphor for interacting with our patients, we encourage the child and adolescent psychiatrist or clinician to set the open frame of mind necessary to help create an atmosphere of curiosity , which facilitates the “figuring out” process of the patient’s and their parents’ or caregivers’ capacity for curiosity of others’ mental states. In doing so, the child and adolescent psychiatrist or clinician will be in a position to know if the verbal discourse matches their nonverbal communication, giving reliability to accuracy of the information disclosed.

The Alliance: Goodness of Fit for Mutual Curiosity

Studies on temperament recognize the importance in having a goodness of fit between a child and his or her parents or caregivers for the child to develop self-regulatory abilities and adaptive models of interactions with others effectively (Huizink 2008). We propose that the concept of goodness of fit between patient (and their parents or caregivers) and the child and adolescent psychiatrist or clinician is equally important in a CDI. Exploring the patient’s and their parents’ or caregivers’ ability to be curious by being curious about them is essential. For example, a jovial child and adolescent psychiatrist with an easy/flexible temperament will facilitate a patient with generalized anxiety disorder to share details about their anxiety. This is because the patient implicitly is reassured by the child psychiatrist’s manner that they will be understood. Further, the jovial child and adolescent psychiatrist may need to make a concerted effort in slowing their tempo—voice and rhythm of verbal inquiry—when interviewing a child and family with a slow-to-warm-up temperament, as his jovial attitude may inhibit the patient if it is perceived as pressure to talk. In contrast, we have seen occasions when child and adolescent psychiatrists approach patients and their family in an overly professional and serious manner, which does not allow for an atmosphere of safety and, in essence, limits the reliability of the information shared by the patient and family.

The Clinician Has an Open Frame of Mind

In child and adolescent psychiatry textbooks, setting the frame of mind by the clinician when interviewing the patient and parents is superficially described as the need to be empathic in order to establish rapport. We have found extant literature about the importance in setting the frame of mind in the child and adolescent psychiatrist or clinician during an integrated developmental biological, psychological, and social contemporary diagnostic interview process. We submit that the frame of mind of the child and adolescent psychiatrist when preparing for a CDI is crucial for gathering information. Setting the frame of mind is essential for creating an atmosphere of safety for the patient and their parents or caregivers in order to increase reliability, consistency, and accuracy in the description of the signs and symptoms they endorse. We cannot emphasize enough that during a CDI, the child and adolescent psychiatrist’s or clinician’s personal attributes and beliefs will undoubtedly influence what and how the patient chooses to share in regard to the problems and symptoms they endorse. The patients (and their parents or caregivers) will be nonconsciously and implicitly (see Chap. 3) looking for nonverbal cues and behaviors by the clinician to learn about his or her frame of mind and authenticity when in the room. The child and adolescent psychiatrist or clinician brings his or her own temperament, cognitive flexibilities, internal working models of attachment , and implicit relational knowing models formed in early childhood to the interaction (see Chap. 5), which will contextually influence what the patient and his family feel comfortable disclosing.

The reader may ask how the child and adolescent psychiatrist or clinician sets his or her frame of mind to allow for bidirectional subjectivities to develop with the patient and parents or caregivers that are conducive for the necessary relational closeness . We define an open frame of mind as when the psychiatrist or clinician meets the patient and their family without preconceived opinions about how patients of certain ages should think and behave. The suspension of analytic thought allows for bidirectional subjectivities to develop. Therefore, the clinician’s assumptions and beliefs regarding what is generally considered normal developmentally will need to be constrained as best as possible during the initial phase of the interview.

The clinician has an open frame of mind

A 16-year-old African-American adolescent female patient had a close relationship with both of her parents, in spite of their divorce two years prior. What led to the evaluation was that when her father began to date another woman, the patient began to feel unhappy and unmotivated about completing her schoolwork. She felt that her father’s girlfriend was critical of the closeness she had with her father, “and my father would just let her criticize me.” The child and adolescent psychiatrist intersubjectively experienced the patient as being genuine and realistic about her current dilemma and stated in a jovial, slightly humorous and somewhat sarcastic manner: “It sounds to me like your father avoids getting in the middle, although he is the one who created the dilemma. This leaves you and his girlfriend needing to figure it out. That seems quite unfair. I think we need to ask your father to openly share that both of you are important to him.” The patient, with excitement and appreciating the sarcasm, responded: “Wow, that’s it. Kind of funny the way you said it. I was letting his girlfriend win when I began to act like a stubborn kid, proving I was immature. My dad set us up, he needs to know I can share him if he tells his girlfriend how much I mean to him.”

The example shows that the clinician’s open frame of mind and authenticity helped the patient reflect on the reasons for her anger and self-defeating behavior . The interaction was facilitated by the personal attributes of the clinician, who had experience in working with adolescents from divorced families. He openly shared his view of the dilemma and, in doing so, cocreated more adaptive ways for the patient to manage her dilemma. The interaction may have had a very different outcome if the clinician had preconceived opinions about the tumultuous conflicts adolescents have with their parents after the parents’ divorce. It may have led the clinician to nonconsciously assume that the patient was somewhat unrealistic, difficult, and demanding, which would have prevented allowing the intersubjective experiences between patient and clinician to guide the process. The clinician’s closed frame of mind may have led him or her to suggest less adaptive solutions to the dilemma based on generalizations about the adolescent’s problem, encourage the patient to limit her wish for closeness with her father, ask the patient to address her father’s girlfriend directly, or hypothesize that the patient’s unhappiness would be best managed with medication, to name a few. Additionally, if the patient struggled with a nonverbal learning disorder or other cognitive limitations, the description of her conflicts with her father may not have been accurate and the clinician would have intersubjectively experienced the patient as superficial and unable to view matters from her father’s vantage.

Herein, the child or adolescent psychiatrist or clinician, by having an open frame of mind during the CDI interview process and regardless of the age of the child or adolescent, can accept that there is no true objectivity without taking into account the intersubjectivity cocreated by all involved.

The clinician’s initial preconceived notion and the importance of culture

A 14-year-old Asian-American adolescent male, who had a close relationship with his parents, began to display oppositional behavior and refused to participate in family activities related to his parent’s Asian culture. He also declined to continue with violin classes, which were important to his parents, who hoped it would lead to a scholarship in music for college. His parents were reluctant to seek psychiatric help, feeling it was a personal family matter. They finally were forced to seek help for their son when he voiced having suicidal ideation to a school counselor. The child and adolescent psychiatrist typically used a jovial and humorous approach. He recognized that culturally his approach could be experienced as disrespectful—unlike in his own culture—and set his frame of mind to approach the family in a tempered manner to allow for the intersubjective experience to guide his approach. In meeting the patient and parents, he felt intersubjectively that the family was not interested in his opinions; they believed their son’s problems were foolish and requested the clinician to reiterate to their son that he had to obey them as they had given him everything he needed to pursue a college education. The patient stated in a sarcastic manner, “I am not their cultural experiment. They do not understand me.” The clinician intersubjectively initially noticed feeling like the parents; the adolescent was being abrasive and unrealistic, a common view where it is thought that firm limit setting by parents is needed. The clinician intersubjectively noticed a wish to step in for the parents asking the patient to appreciate their efforts to educate him. In doing so, the clinician recognized that his feelings stemmed from an implicit relational pattern familiar in his family: “children should be seen and not heard.” With this in mind, he recognized that he did not have an open mind, as he had preconceived notions about what the family needed, which did not allow his intersubjective experiences to guide him. With this realization, he opened the intersubjective field and was able to take the vantage point of the cultural dilemmas in both parties (the parents, Asian, and the patient, Asian-American). He proceeded to say, “This must be difficult for all of you. As parents, you are correct in wanting to remain culturally loyal to your values and beliefs, and your son is also correct on wanting to fit in his peers’ social and cultural environment.” This allowed the parents to consider the possibility that their son’s oppositional behavior was due to the fact that he was struggling with integrating the social and cultural discrepancies in his life and was hoping for his parents’ understanding.

This example captures the potential difficulties that can be created when the clinician has a preconceived opinion of the nature of the patient and family’s situation. In this case, he had a preconceived notion that because the family was Asian, their beliefs and values needed to be respected and adhered to. Fortunately, in allowing the intersubjectivity cocreated with the adolescent to guide the process, he recognized that his preconceptions were limiting his ability to help the adolescent.

8.4 The Four Pillars of the Contemporary Diagnostic Interview

Mental illness does not exist in a vacuum; it is a set of signs and symptoms that affects a person within the context of their personality and their environment. The treatment must be of the person and not only of their illness. The four pillars of a CDI are essential for understanding a patient from the inside out. The authors define the four pillars of a CDI as those that define a person’s unique personality within the context of others. The four pillars are the synergy of innate and environmental processes that become the blueprint of how a child learns to develop and maintain self-regulatory abilities and unique implicit relational patterns to successfully interact with others.

The first three pillars—temperament, cognition, and cognitive flexibility—form the foundation of the fourth pillar, internal working models of attachment (IWMA). By understanding the contribution from each of the pillars, the clinician will have a true biopsychosocial understanding of the patient and their parents or caregivers, as well as their needs.

Although many psychodynamic and attachment-theory-based texts pay limited attention to temperament and cognitive functioning in forming personality, contemporary developmental research has demonstrated that an individual’s genetic makeup is a determining factor in the formation of a personality, which some consider the basis of the psychodynamic self (Mancia 2006).

We now will review each of the four pillars obtained during a CDI. The pillars are outlined in the order in which they emerge in the psychological development of a person. We note that when using a CDI, the four pillars are simultaneously elucidated.

8.5 Temperament

Temperament refers to the “stable moods and behavior profiles observed in infancy and early childhood” and came to the forefront in developmental psychology and child psychiatry in the 1960s and 1970s (Chess et al. 1960). Thomas and Chess (1999) are recognized for their landmark scientific contribution to the study of temperament. Their seminal work has achieved general consensus in that its expression has been consistent across situations and over time. In their study, Thomas and Chess longitudinally evaluated 141 children over 22 years, from early childhood until early adulthood (1982, 1986). Over the course of the evaluation, nine temperament traits became apparent.

Temperament Traits Derived from Thomas et al. (1970)

Activity level

Rhythmicity or regularity

Approach or withdrawal responses

Adaptability to change

Sensory threshold

Intensity of reactions

Mood

Distractibility

Persistence when faced with obstacles

The work of Thomas and Chess confirmed what the British psychoanalyst and father of attachment theory, John Bowlby , MD (1907–1990), had hypothesized: A child’s temperament influences how the child is experienced by their parents and significantly shapes how the parents interact with the child (Bowlby 1999). This way of thinking, where an active and bidirectional relationship exists between the child and caregiver, represented a significant point of divergence from the previously accepted understanding of the infant as a passive recipient and product of his or her environment (Mahler 1974). In essence, the child was seen as a full contributor to the “goodness of fit ” (Thomas and Chess 1999) between the child and the parents or caregivers. The issue of goodness of fit between patient, parents, and clinicians is often overlooked in spite of it being one of the most significant factors that lead to successful evaluation processes (see section “The clinician has an open frame of mind” this chapter).

Thomas et al. (1970) found that “some children with severe psychological problems had a family upbringing that did not differ essentially from the environment of other children who developed no severe problems” and later added that “domineering authoritarian handling by the parents might make one youngster anxious and submissive and another defiant and antagonistic.” Thus, “theory and practice of psychiatry must take into full account the individual and his uniqueness” (Thomas and Chess 1977). Furthermore, it is important to note that temperament in infancy and early childhood is influenced not only by heredity but also by environmental experiences (Emde and Hewitt 2001). A review of the literature regarding child temperament reveals that much research has evolved in developmental psychology since the early work of Thomas and Chess 30 years ago, although some controversies remain (Kagan 2008, Rothbart and Bates 2006, Zentner and Bates 2008). In essence, the matter of temperament is multifactorial—it involves genes, neurobiology, and the individual’s capacity to interact with others in an acceptable manner—and “its regulation is culturally dependent” (Paulussen-Hoogeboom et al. 2007).

Temperament Styles

In Thomas and Chess’ New York Longitudinal Study of 141 youth (Thomas and Chess 1982), they described temperament as having four general styles; 45 % were classified as “easy or flexible,” 15 % as “slow-to-warm-up,” 10 % as “difficult or feisty,” and 35 % as “mixed,” a combination of the three (Thomas and Chess 1999).

While this may not seem surprising, the knowledge of these temperament styles may guide the child and adolescent psychiatrist or clinician in having realistic expectations based on the understanding of how genetic and biological factors contribute to the variability of a patient’s psychological responses to life events. When recognized, certain clusters of temperament traits can be predictive. In a given situation, for example, the combination of negative mood , high intensity, irregularity, and slow adaptability might point to a “difficult” child who is likely to have and cause problems during their life and who may have difficulties with a two-person relational psychotherapeutic approach and may be best suited for behavioral approaches. Conversely, those with a cluster of positive mood, positive approach, and high adaptability usually can benefit from a two-person relational psychotherapeutic approach.

The Easy or Flexible Temperament Style

This style was found to be present in approximately 45 % of the children studied by Thomas and Chess (1999). The child or adolescent with an easy or flexible temperament style typically has a history of being happy overall and not easily upset by negative news or events. They typically can transition, with a display of healthy and mild forms of anxiety , from conflicted situations to a positive stance and engage in a cooperative approach with others. Generally, children with this type of temperament who have grown with secure internal working models of attachment do not show up to our office unless an adverse life event occurs that creates disequilibrium in their self-regulatory abilities or in their family system.

Jason was a 13-year-old adolescent who had an easy and flexible temperament and a secure form of attachment. He had been doing well until the unexpected death of his father in a car accident 1 month before his referral for psychotherapy. Although Jason was doing well in school, his mother brought him to psychotherapy because “since his father died, his personality has changed.” When the family learned of the father’s death, Jason began to wear his father’s T-shirts to school, stating that “they help me keep going on.” Jason was of above-average intelligence, empathic, and eager to talk about his feelings because “I know my father’s death is bothering me” (Delgado 2008).

The Slow-to-Warm-Up Temperament Style

The child or adolescent with a slow–to–warm–up temperament style (present in 15 % of the children studied) can quickly withdraw when faced with new and difficult situations that involve complex issues with some degree of uncertainty. Children and adolescents who present with anxiety and shyness may have the temperament style conducive to two-person relational psychotherapy in which the psychotherapist learns to match intersubjectively the patient’s tempo of interaction, which allows for an atmosphere of safety to cocreate healthy models for self-regulation.

Bobbie was a 5-year-old girl who was referred by her pediatrician due to severe constipation not due to a medical condition. A trial of laxatives, including mineral oil, were not only unsuccessful but also made her feel “embarrassed and sad; she would leak the mineral oil all over herself and not have a bowel movement.”

Bobbie’s family was by all standards well adjusted and healthy. Bobbie was an intelligent and shy girl who related well to her family. She demonstrated a slow-to-warm-up temperament, in that she feared playing with friends and preferred to stay close to home due to her abdominal pain from constipation. Her slow-to-warm-up temperament was also evident in the evaluation process. Bobbie began a two-person relational play therapy in a rather constricted manner, as was expected. Over a short period of time, she felt comfortable with the psychotherapist and began to enjoy the vitality cocreated through their play. The new emotional experience permitted her to develop healthier ways of managing her anxiety (Delgado 2008).

The Difficult or Feisty Temperament Style

The child or adolescent with the difficult or feisty temperament style (present in 10 % of the children studied) often avoids or refuses to interact with others unless they can control the interaction. They often create distance when not feeling they are in charge of the interaction and at times resort to aggression. This temperament style is often thought of as being part of a continuum with disorganized internal working models of attachment, and it is diagnostically thought of as having oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) or disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD).

The child with difficult/feisty temperament style frequently behaves poorly in the child and adolescent psychiatrist’s or clinician’s office and makes statements like, “I hate being here. I am not going to cooperate; I don’t need this torture.” In approaching this child, it will be important to determine the degree to which the difficult/feisty temperament style is typical or if this reflects the child’s fear and anxiety attributable to the evaluation process. This can be achieved through a here-and-now intersubjective experience .

Ernie, a 5-year-old boy, had persistent behavioral patterns with an angry and irritable mood. He was also argumentative and displayed defiant behavior toward authority figures. He was expelled from two day care centers due to the intensity of his negative behavior toward others. When redirected or when limits were set, he would yell and blame the day care providers for being angry at him. His parents believed that the day care center children were provoking their son and that the day care staff was instigating the difficulties because they did not like their son. The parents and son viewed the world through the lens of a difficult/feisty temperament and disorganized internal working models of interaction.Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree