Pychogenic Gait: An Example of Deceptive Signaling

John G. Morris

Gregory Mark de Moore

Marie Herberstein

ABSTRACT

Psychogenic gaits are characterized by a number of features (1): exaggerated effort or fatigue (often with sighing), extreme slowness, convulsive shaking (with “knee buckling”), fluctuations (with periods of normality), unusual postures, and bizarre movements. The onset may be abrupt; a sudden “cure,” albeit short-lived, may also occur. Pain may be prominent, particularly where the problem follows an injury. There are usually no objective neurologic signs relevant to the disability, though a psychogenic gait may also complicate the presentation of a true physical disorder, with its associated signs. A psychiatric assessment often fails to identify a significant underlying psychiatric disorder such as major depression or psychosis. The current classification of psychogenicity lays much emphasis on the distinction between patients who knowingly seek to deceive and those in whom the behavior is unconscious. In practice it is often hard to make this distinction. There is a growing literature on behavioral deception in animals where the question of insight on the part of the deceiver does not arise. Behavioral deception in animals is discussed in terms of signaling and its effect on the receiver (2). Deceptive signals, by definition, benefit the deceiver and are costly to the receiver. That this behavior is so widespread affirms its value to those who practice it. Psychogenic behavior in humans equates most closely with injury-feigning, seen, for example, in chimpanzees, which induces nurturing behavior in receivers of the same species, or protects the signaler from stronger or more aggressive members of the group. The hallmark of the psychogenic gait is its emotive quality; it signals to the observer both disability and distress, and induces nurturing behavior. It is best conceived as an acquired behavioral response to stress in a predisposed individual.

INTRODUCTION

Neurologists training in the latter part of the 20th century were discouraged from applying the label of hysteria to patients with neurologic symptoms that could not be readily explained on the basis of any underlying physical disease. Interns who exposed “give-way” weakness, midline splitting of sensory loss, and distractible tremors were given dire warnings by their seniors that many such patients have, or go on to develop, major neurologic diseases. Eliot Slater’s farewell address to his neurologic colleagues at the National Hospital, Queen Square, was often cited (3). In this scholarly essay, Slater quoted some of the great neurologists who have given this matter their attention (“Hysteria … the mocking bird of nosology”; “… as much a temperament as a disease …”; the diagnosis of “hysterical paralysis” is a “a negative verdict”; hysteria is “only half a diagnosis”) before drawing, like Brain (4)

before him, a distinction between adjectival and substantival views of hysteria. While it might be acceptable to label a symptom as hysterical, there was no justification for accepting hysteria as a syndrome: “Both on theoretical and practical grounds it is a term to be avoided.” In 49 of 85 patients diagnosed as having hysteria in the years 1951, 1953, and 1955 at the National Hospital, Slater and Glithero (5) subsequently found an underlying organic illness. While this study has since been criticized on many grounds, it had a profound effect on neurologic practice for some decades to follow. Of even greater influence was David Marsden who, with Stanley Fahn, founded the subspecialty of movement disorders. One of Marsden’s many achievements was to rescue organic disorders such as torticollis and writer’s cramp from the “no man’s land” of hysteria. While he wrote with his customary flair and authority on the subject of hysteria (6), Marsden himself was reluctant to make the diagnosis.

before him, a distinction between adjectival and substantival views of hysteria. While it might be acceptable to label a symptom as hysterical, there was no justification for accepting hysteria as a syndrome: “Both on theoretical and practical grounds it is a term to be avoided.” In 49 of 85 patients diagnosed as having hysteria in the years 1951, 1953, and 1955 at the National Hospital, Slater and Glithero (5) subsequently found an underlying organic illness. While this study has since been criticized on many grounds, it had a profound effect on neurologic practice for some decades to follow. Of even greater influence was David Marsden who, with Stanley Fahn, founded the subspecialty of movement disorders. One of Marsden’s many achievements was to rescue organic disorders such as torticollis and writer’s cramp from the “no man’s land” of hysteria. While he wrote with his customary flair and authority on the subject of hysteria (6), Marsden himself was reluctant to make the diagnosis.

Faced with a patient who did not appear to have a neurologic disease yet was disabled by neurologic symptoms, neurologists turned to their colleagues in psychiatry, only to be told, in most cases, that there was no major psychiatric disease present. Often, there was anxiety and depression, but these, perhaps, were understandable in the circumstances. The term “hysterical,” long contaminated by its everyday use, was replaced by “psychogenic,” but the problem of how to think about these patients and, more important, manage them, remained. Psychogenic disorders account for a sizeable proportion of referrals to neurology clinics, and it is time that this important yet neglected aspect of neurologic practice receives the attention it is due.

In this chapter, we will discuss the key diagnostic features of the psychogenic gait by reviewing a number of specific cases. The hallmark of the psychogenic gait, namely, its emotive quality, will then be discussed in the light of the current classification of psychogenic disorders, and then from the perspective that this is an example of deceptive signaling, a common pattern of behavior throughout the animal kingdom.

CASES

A. Psychogenic Gait in Neurologic Disease

One of the most difficult and demanding roles of the neurologist is distinguishing psychogenic from “real” symptoms in a patient with proven neurologic disease. This is illustrated in the first two cases.

Case 1

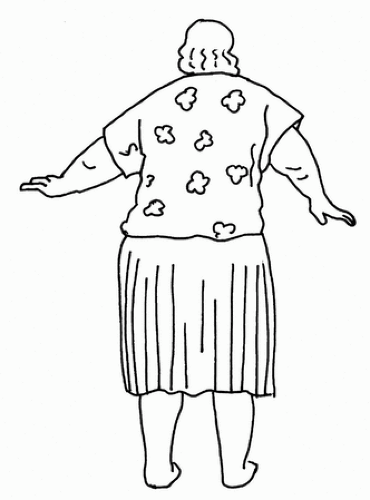

A 67-year-old woman presented with a 10-year history of “collapses.” These began after she discovered an indiscretion by her husband. There were bouts of tremor of the limbs. She had become disabled and dependent on her husband; by the time of her referral to our clinic, she was using a wheelchair outside the home. During the consultation, her manner was one of forced jollity. On standing, she developed a coarse tremor of her trunk and legs which settled after a minute or so. She then walked very slowly on a broad base with her arms extended in the manner of a tightrope walker (Fig. 10.1). While sitting in the chair, she developed a gross tremor of the right leg when it was extended, which was abolished by getting her to tap with the left foot at a varying rate set by the examiner. A diagnosis of psychogenic gait was made, but a tremor study confirmed the presence of a 16-Hz tremor in the legs. This patient had impairment of balance due to orthostatic tremor. She was a vulnerable person with marital problems and there was undoubtedly embellishment. With a program of rehabilitation, her confidence improved and with it, her gait.

Case 2

A teenage girl suddenly developed a generalized tremor and difficulty walking. She walked on a broad base with her feet inverted and her arms held out beside her. Her body bounced with a coarse tremor which increased in amplitude when she sat down, causing the couch to creak. As a child she had had a number of strokes, and an angiogram showed the typical features of Moya Moya disease with occlusion of the internal carotid arteries and the opening up of multiple co-lateral vessels. An MRI scan, performed after the onset of the tremor, showed a large area of infarction in the distribution of the right middle cerebral artery; this was unchanged

from imaging studies she had had as a child. There were no signs on clinical examination, which could be related to the area of infarction. The problem continued and she had several admissions to the hospital. During one of these, she was seen to walk normally at a time that she thought she was unobserved. After 18 months she was cured by a faith healer. She then walked quite normally for several years until she gave birth to three children in three years. At this time of great emotional stress and physical exhaustion, her tremor and gait disturbance returned. She was treated as an inpatient with rehabilitation and made a rapid recovery. She was a girl of modest intelligence who had difficulty coping with the trials of adolescence and then motherhood, and expressed this through her physical symptoms; her many admissions to the hospital as a child may have influenced this process. While she had an undoubted underlying neurologic disease, which may have made her less able to cope with life’s stresses, this had not caused her tremor and gait disturbance.

from imaging studies she had had as a child. There were no signs on clinical examination, which could be related to the area of infarction. The problem continued and she had several admissions to the hospital. During one of these, she was seen to walk normally at a time that she thought she was unobserved. After 18 months she was cured by a faith healer. She then walked quite normally for several years until she gave birth to three children in three years. At this time of great emotional stress and physical exhaustion, her tremor and gait disturbance returned. She was treated as an inpatient with rehabilitation and made a rapid recovery. She was a girl of modest intelligence who had difficulty coping with the trials of adolescence and then motherhood, and expressed this through her physical symptoms; her many admissions to the hospital as a child may have influenced this process. While she had an undoubted underlying neurologic disease, which may have made her less able to cope with life’s stresses, this had not caused her tremor and gait disturbance.

B. Gait in Major Psychiatric Disease

Gait disorders not uncommonly occur in the setting of major psychiatric disease and exposure to neuroleptic drugs.

Case 3

A young man with a 5-year history of schizophrenia, for which he had been treated with a number of neuroleptic drugs including fluphenazine and thioridazine, was referred because his father was concerned over the young man’s gait. While sitting and conversing, he flapped his hands. Before attempting to walk, he wiggled his toes repeatedly and then walked in a curious creeping manner on his heels with his toes extended. In view of his long exposure to neuroleptic drugs, the posturing of his feet might have represented a form of tardive dystonia. When he put on his thongs, however, he walked quite normally, though before initiating gait he usually wiggled his toes. This patient had a stereotypy of his hands; his gait was ritualistic and related to his psychosis. It is probably better to distinguish this type of gait, which may be seen as another facet of psychotic behavior, from psychogenic gait, where the patient is signaling distress and disability (see below).

C. “Pure” Psychogenic Gait

The diagnosis of psychogenic gait is made with more confidence in younger patients, in whom the likelihood of an underlying physical cause is lower than in the elderly. It is also reassuring if there are no objective physical signs.

Case 4

A 9-year-old boy developed tremor of his hands and a gait disturbance. The tremor, which appeared when the arms were raised, was distractible and the gait disturbance only occurred during the examination when he was asked to walk heel-to-toe. He then threw himself into a series of wild gyrations, flinging his arms about and leaping from one foot to another, while somehow staying upright, thereby revealing, if nothing else, that there was no problem with his balance. There were no other physical signs. He was of below average intelligence. His mother had multiple sclerosis. With firm encouragement and reassurance, he made a full recovery.

Case 5

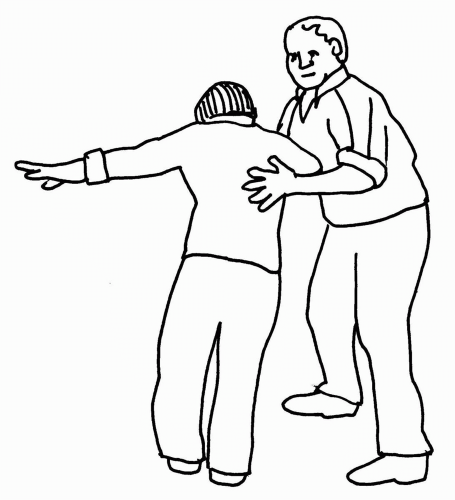

A young woman who was a champion athlete came to the clinic with her coach, having suddenly lost her balance and her ability to open her left eye. She walked slowly and gingerly with her arms held out and fell repeatedly into the arms of her coach, who shadowed her for fear that she would fall and injure herself (Fig. 10.2). There were no objective signs. Her left eye was closed. That this was a “pseudoptosis,” due to sustained contraction of orbicularis oculi rather than weakness of levator palpebrae superioris, was demonstrated by the fact that the eyebrow was lower on the affected side (not higher as usually occurs in patients with true ptosis where an attempt is made to overcome the ptosis using frontalis). The presence of this “false” sign was helpful in confirming the diagnosis of psychogenic gait. Extensive investigations, including imaging of the brain and spinal cord, had proven negative.

Case 6

A man of middle age miraculously escaped injury when a tree fell onto the hood of his car in a high wind. He was

severely shaken, and over the next few weeks began to have increasing difficulty in walking. He consulted a lawyer and, at the time of assessment, was bringing an action against the local council to whom the tree belonged. He walked with extraordinary slowness, pausing repeatedly and panting as though he were climbing a mountain. After a few steps, his knees buckled and he sank to the floor. There were no objective physical signs and all investigations were negative.

severely shaken, and over the next few weeks began to have increasing difficulty in walking. He consulted a lawyer and, at the time of assessment, was bringing an action against the local council to whom the tree belonged. He walked with extraordinary slowness, pausing repeatedly and panting as though he were climbing a mountain. After a few steps, his knees buckled and he sank to the floor. There were no objective physical signs and all investigations were negative.

Case 7

A 41-year-old woman presented with a 10-year history of gait disturbance, poor vision, and difficulty in swallowing and speech. At times, her jaw would lock. On examination, she had a hobbling gait. She appeared to be in pain and leaned heavily on her walking stick. After a few steps, she leaned back heavily on the wall as though exhausted. She had a curious stammer, repeating whole syllables, rather than consonants (a feature of psychogenic stutter noted by Henry Head) (7), and enunciating words in an infantile fashion. Her face radiated misery and anguish. She professed to be completely blind, though she found her way around the room without bumping into the walls or furniture. Her hearing was normal but she incorrectly localized, by pointing, the direction from where the examiner’s voice emanated. There were no objective neurologic signs. While the gait had no features particularly suggestive of a psychogenic disorder apart from the effort involved, the presence of psychogenic stutter and blindness were helpful in confirming the presence of a psychogenic gait.

Case 8

A young woman became numb from the neck down the day after a minor car accident. Subsequently, she developed a stammer, gait disturbance, and a tendency to strike herself with her right arm. She had had an abusive and unhappy childhood. After the break-up of her marriage, she had been admitted to a psychiatric unit with “nervous exhaustion.” All investigations had been negative. Litigation was pending. On examination, she stammered as described in Case 7. She had a curious creeping gait punctuated by sudden bouts in which she clasped her back in apparent pain (Fig. 10.3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree