Questionnaire, Rating, and Behavioural Methods of Assessment

John N. Hall

The earliest forms of psychiatric assessment were based on direct interviews with patients, on reported observations by those who knew the patient, and on direct observations by attendants—later nurses—in the care setting. Attempts to codify these forms of assessment had begun over 90 years ago, as illustrated by the ‘Behavior Chart’ of Kempf.(1) The present range of structured psychiatric assessment methods grew from the 1950s in association with the introduction of neuroleptic medication and the development of psychiatric rehabilitation programmes. The two most frequently used types of systematic and structured assessment used in both clinical practice and research continue to be questionnaires and ratings. Their value lies in the systematic coverage of relevant content, and the potential for comparing scores across individuals and groups and over time.

This section covers assessment methods that are appropriate for both self-report by patients and others—questionnaires—and observations and judgements made by others about the patient and their immediate circumstances—rating methods. This section will also briefly describe behavioural approaches to assessment of clinical relevance.

Questionnaires offer the respondent a preset range of written questions covering the area of clinical interest, such as depression. The questions are usually completed by marking one of a set of provided response categories (forced-choice questions), but may be completed by the patient writing their own response in free text. Self-report and ‘self-monitoring’ methods are similar to the latter form of questionnaire, in that the patient completes a diary or premarked sheets. These are more open-ended, and any associated thoughts of the patient may be included. Self-report measures are used widely in cognitive behavioural interventions.

Ratings are judgements about the quality or characteristics of a defined attribute or behaviour, completed subjectively, or on the basis of direct observation of the behaviour in question. While questionnaires are usually self-completed, ratings may be completed by one person with respect to another person. In psychiatric practice, ratings include those made by professional staff, often a nurse or care worker, or by a family member or informal carer, about a patient.

Ratings and behavioural measures have a special use in the assessment of disturbed or bizarre behaviour, where the patient may have little insight or knowledge of the nature or degree of their disturbance, which may pose a major ongoing management problem, or a barrier to their placement in the community. An example of such a measure is the Aberrant Behavior Checklist.(2) This is a 58-item behavioural rating scale completed by an informant, with the content covering five subscales: irritability, agitation, and crying; social withdrawal and lethargy; stereotyped behaviour; hyperactivity and non-compliance; and inappropriate speech.

The purpose of questionnaire, rating, and behavioural assessments

Scales may be used for a number of purposes:

for the initial assessment of a patient as part of a clinical formulation

for ongoing monitoring during the course of treatment

as outcome measures

for assigning patients from a larger population to a particular therapeutic regime

for service planning

Normally an assessment will focus on the presented or referred patient. However, it may be helpful to either focus on a family member or on a formal or informal direct carer of the patient. Another potential focus is the patient’s environment. The range of behaviour a patient can display is limited by the physical nature of their environment, by the range of equipment or materials available to the patient, and by the social rules of the setting (such as rules against smoking). A rating of environmental restrictiveness would then survey both environmental constraints and the range of formal institutional regulations and informal rules followed by care staff.

Most measures simply describe the current functioning of the patient, without offering a framework for translating the obtained scores into clinical priorities for treatment. An important development in rating methodology has been the ‘needs assessment’ approach that incorporates the views of patients and carers when taking into account the extent to which their needs have been met, or remain unmet. The Camberwell Assessment of Need (CAN) family of measures(3) has adopted a consistent set of content domains, which has been applied to separate need assessment schedules which can now be applied to adults, older adults, people with learning disabilities, and in forensic settings.

Scale content

A questionnaire or rating is defined by both overall content and item format. The content of a measure should logically be determined by its purpose. One model of assessment(4) suggests that there are four main content areas for assessment, including cognition, affect (including verbal-subjective components of behaviour), physiological activity, and overt behaviour. The content should cover all the domains of clinical relevance, including current and past behaviour, and psychopathology. While most rating scales cover a relatively limited number of functional areas, and are often designed for use with a specific client group or clinical population, some measures are designed for wider use.

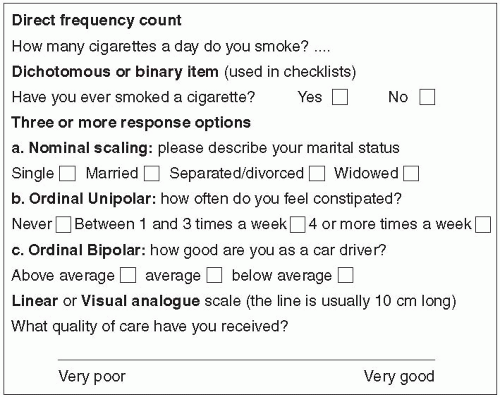

The format of each item typically consists of an item stem, or question, followed by a set of response options. The item stem and responses should be grammatically complementary, and the total set of response options for each item should together cover all logically possible response options. Responses should use exact frequencies (such as ‘twice a day’ or ‘at least every hour’) rather than vague terms such as ‘often’ or ‘frequently’. Response options may be set out verbally, or may have a numerical value attached. Usually the responses for each item will be laid out in sequence to form a graded series of increasing or decreasing severity or quality of response. These items may be set out in unipolar (where one end is ‘zero’ or nil occurrence) or bipolar (with the mid-point being neutral or ‘normal’) form. In general, if an item has more than five response options there is a risk of poor reliability. Figure 1.8.4.1 illustrates the most common individual item formats.

Most items in questionnaires and rating scales are designed to produce ordinal scores—that is, the score simply gives the relative order of items, without implying any mathematical equality of the differences between scores. This limits the statistical methods that can be used with the scores arising from these measures.

Criteria for evaluating questionnaires and rating scales

There are a number of technical and practical factors to bear in mind in appraising and selecting a measure. Anyone using a published questionnaire or rating scale should examine the technical qualities of the measure, which should be included in the original publication or on a scale manual. This is both to critically assess whether or not a specific measure is suitable for the intended purpose, and also to understand how best to use the scale in practice— including any training requirements.

Psychometric adequacy

Psychometric criteria are the most important technical ways to evaluate the quality of a measure. Chapter 1.8.3 outlines those minimum psychometric principles and properties that are applicable to all psychological measures, including the classical approaches to scaling, reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change, as well as generalizability approaches. The most widely known psychometric requirements of any scale are validity and reliability: neither of these are inherent properties of a scale. Scales are valid for specific purposes, which should be clearly described in the original published article about a scale.

The form of reliability most characteristic of rating scales, and of other behavioural measures, is inter-rater or inter-observer reliability, which examines the similarity of scores when two or more different raters administer a scale. Ideally the manual for a scale should describe a rater training procedure. If not, it is always sensible to carry out some basic rater training, carrying out some assessments prior to the main study, analyzing score discrepancies, and ensuring that raters have discussed these differences and why they arose.

Typically, ratings may be completed after an observation period varying from a few minutes or hours, to a few days. For those ratings based on observation periods of more than a day, there is then a variable delay between the relevant observations and the completion of the rating, and also any one observer will only have been present or on duty for a proportion of the observation period. Unless the observer against whom reliability is being assessed is observing for exactly the same period, the periods of observation will not be coincident. Under these circumstances a double rating may not be strictly a reliability check, but more of a check of the stability of the behaviour. Patel et al.(5) discuss how the use of a simple checklist of the occurrence of key events can substantially improve the reliability of this type of scale.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree