32

Recognizing, Assessing, and Treating Seizures and Status Epilepticus in the ICU

Introduction

Seizures and status epilepticus (SE) are common in the ICU. This chapter presents a practical approach to the diagnosis and treatment of nonconvulsive seizures (NCSz) and refractory status epilepticus, the use of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) in critically ill patients, and seizure prophylaxis.

Epidemiology

Seizure is a common complication of critical illness. Clinical seizures, mostly generalized tonic–clonic seizures (GTCSs), occur in about 3% of patients admitted to an ICU. In those patients, the prevalence of NCSz – seizures with subtle clinical manifestations and purely electrographic seizures – is 15–20% overall. The risk is higher in certain populations such as those with acute brain injury, especially intracranial hemorrhage and CNS infection. NCSz or nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) occurs in almost half of patients treated for generalized convulsive status epilepticus (GCSE). There is a correlation between the degree of impairment of consciousness and the prevalence of seizures in the ICU, with comatose patients having the highest rate. Children are also at higher risk.

Etiology of seizures and status epilepticus in the ICU

Etiologies are diverse and are summarized in Table 32.1. The most common causes are drug withdrawal (AEDs, benzodiazepines, and barbiturates), acute stroke, anoxic brain injury, and metabolic/septic encephalopathy.

Clinical manifestations and differential diagnosis

The manifestations of seizures and SE are protean. Of all the subtypes of seizures and SE described, the three semiologies most commonly encountered in the ICU are generalized tonic–clonic, myoclonic, and nonconvulsive.

The typical manifestations of GTCS are often altered in critically ill patients, and out-of-phase clonic movements, asymmetric seizures, or prolonged postictal states are frequent. If the seizure progresses to GCSE, the generalized clonic movements will become progressively less prominent as the patient transitions to NCSE, during which the motor activity may ultimately be absent or limited to minor manifestations (see the following text).

Table 32.1. Etiology of seizure and SE in the ICU.

| Acute brain injury |

| Ischemic stroke |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage |

| Subdural hematoma |

| Traumatic brain injury |

| Anoxic brain injury |

| Infections: meningitis, encephalitis, brain abscess |

| Autoimmune/paraneoplastic diseases, including limbic encephalitis |

| Head trauma: contusion, subdural hematoma |

| Neoplasms: primary or secondary |

| Hypertensive encephalopathy and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) |

| Demyelinating disorders |

| Post-neurosurgical supratentorial procedure |

| Metabolic abnormalities |

| Hyponatremia |

| Hypocalcemia |

| Hypophosphatemia |

| Hypomagnesemia |

| Hypoglycemia |

| Nonketotic hyperosmolar hyperglycemia |

| Renal failure |

| Liver failure |

| Vitamin deficiency (pyridoxine) |

| Systemic infection/sepsis |

| Medications/drugs/toxins |

| Recreational drugs: cocaine, amphetamines, phencyclidine, heroin |

| Antibiotics: beta-lactams (especially cefepime, ceftazidime, and imipenem), isoniazid (through pyridoxine deficiency) |

| Antidepressants: bupropion |

| Antipsychotics: clozapine, lithium |

| Immunosuppressive drugs: cyclosporin A, tacrolimus |

| Others: 4-aminopyridine, theophylline |

| Alcohol withdrawal |

| Drug withdrawal |

| AEDs |

| Benzodiazepines |

| Barbiturates |

| Chronic epilepsy |

CAUTION!

CAUTION!Myoclonic seizures (MSz; epileptic myoclonus) and myoclonic status epilepticus (MSE) are characterized by bilateral myoclonic jerks affecting the face, the trunk, or the limbs. The jerks can be regular, symmetric, and synchronous, such as those that occur in anoxic brain injury, or multifocal, irregular, and sporadic, such as those that tend to occur in metabolic or toxic encephalopathy. The amplitude varies from very subtle to large. The differential diagnosis of epileptic myoclonus includes nonepileptic (subcortical and brainstem) myoclonus, which is also frequently encountered in acutely ill patients with multiple-drug regimens, anoxia, or metabolic imbalances. The differentiation can be difficult, especially in the absence of a clear EEG correlate to the jerks. As a rule, the presence of frequent myoclonic jerks with a nearly normal level of consciousness is incompatible with a diagnosis of MSE.

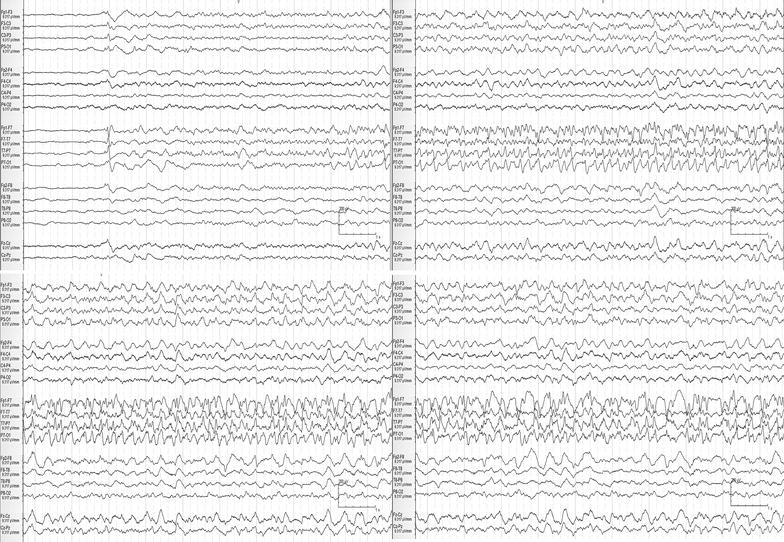

By definition, NCSz and NCSE have subtle or absent clinical manifestations. A thorough examination including careful observation of spontaneous eye and pupillary movements and of the face and limb extremities is needed. Seizures manifesting as pseudo-arousals, with eye opening and semi-purposeful movements, are not uncommon and are often overlooked (Figure 32.1). Autonomic dysfunction, including arrhythmias and blood pressure instability, is a possible manifestation.

The vast majority of seizures in critically ill patients are nonconvulsive. In fact, acute events with obvious clinical (mostly motor) manifestations are more likely to be nonepileptic and include clonus, tremor, shivering, nonepileptic myoclonus, and semi-purposeful movements.

EEG in the management of seizures and status epilepticus in the ICU

EEG and continuous EEG (CEEG) monitoring are central to the diagnosis and treatment of seizure and SE, as recently stressed in the Neurocritical Care Society guidelines. Fifty percent of patients with NCSz will have their first seizure identified by a 1-h study, and 95% by a 24-h study. A longer duration of 48 or more hours is often needed in comatose patients and in patients with periodic discharges, as their first definite seizures are often delayed.

CAUTION!

CAUTION!The EEG during GTCS is usually difficult to interpret because of muscle artifact. When visible, the tonic phase is characterized by generalized, medium-high–voltage, approximately 10-Hz activity. This activity gradually slows as the clonic phase begins, becoming bursts of generalized polyspikes alternating with periods of attenuation. During the postictal period, the EEG shows generalized slowing and attenuation.

Several EEG patterns have been described in association with MSz and MSE. After anoxic brain injury, the EEG consists of generalized periodic discharges (GPDs) or a burst–suppression pattern, although sometimes there is no EEG correlate to postanoxic myoclonus. The myoclonic jerks are usually synchronous with the GPDs or the bursts, and both increase with stimulation. In MSz and MSE of toxic and metabolic cause, jerks are often synchronous to multifocal spikes or spike-and-wave complexes.

The EEG patterns associated with NCSz and NCSE include a number of generalized and focal discharges. EEG criteria for definite NCSz have been published (see Table 32.2), but there are other patterns that can be seen in NCSz.

It is often difficult to distinguish ictal, interictal, and nonictal patterns in encephalopathic patients. Lateralized periodic discharges (LPDs; also known as periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges [PLEDs]) or GPDs are sometimes associated with clinical manifestations and in these cases have to be considered and treated as an ictal pattern. In most comatose patients, however, similar patterns lack any obvious clinical correlate, and it is impossible to infer their ictal nature. It is important to acknowledge this lack of certainty and avoid dogmatic and categorical views. We often refer to equivocal patterns as being on an interictal–ictal continuum, recognizing that they may sometimes be ictal and sometimes not, even in the same individual at different times (Figure 32.2).

Figure 32.1. Left temporal seizure in a 22-year-old man with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection-related refractory NCSE. Many seizures were purely electrographic. Some were accompanied by subtle manifestations, including pseudo-arousal, eye opening, and oral automatisms. NCSE was preceded by nonspecific prodromal symptoms (headache, low-grade fever, and photophobia) and a GTCS. He required sedation with anesthetic drugs (midazolam, propofol, ketamine, and finally pentobarbital) for about a month in addition to multiple AEDs. He had an excellent cognitive outcome (normal and high functioning) despite a prolonged course of SE. Four consecutive pages of EEG are shown. High-pass filter is at 1 Hz, low-pass filter is at 70 Hz, and notch filter is off.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree