The Doloplus-2 was developed in France and was one of the first tools of this kind [56]. At the time of this writing, an English translation of the scale was available at www.doloplus.com/travaux/travaux6.php. The tool consists of five somatic (e.g., protection of sore areas, sleep patterns), six psychosocial (e.g., communication), and two psychomotor (i.e., washing/dressing and mobility) items that are scored along 0–3 scales, with the anchor for each of the scales being clearly defined. The psychometric properties of the Doloplus-2 are satisfactory but, in a clinical investigation of three scales (i.e., the PACSLAC, the PAINAD, and the Doloplus-2), participating nurses found the Doloplus-2 to be less clinically useful [61], possibly because the Doloplus-2 relies on prior knowledge of the patient.

The Abbey Scale consists of only six items (e.g., facial expression, change in body language, physiological change, physical change) rated from 0 to 3, and the PAINAD consists of five items (e.g., breathing, negative vocalization, facial expression) rated from 0 to 2. Both the Abbey Scale and the PAINAD have been shown to have good psychometric properties, although [25, 61] their coverage of the nonverbal pain assessment domains recommended by the American Geriatrics Society is more limited than that of the PACSLAC scales.

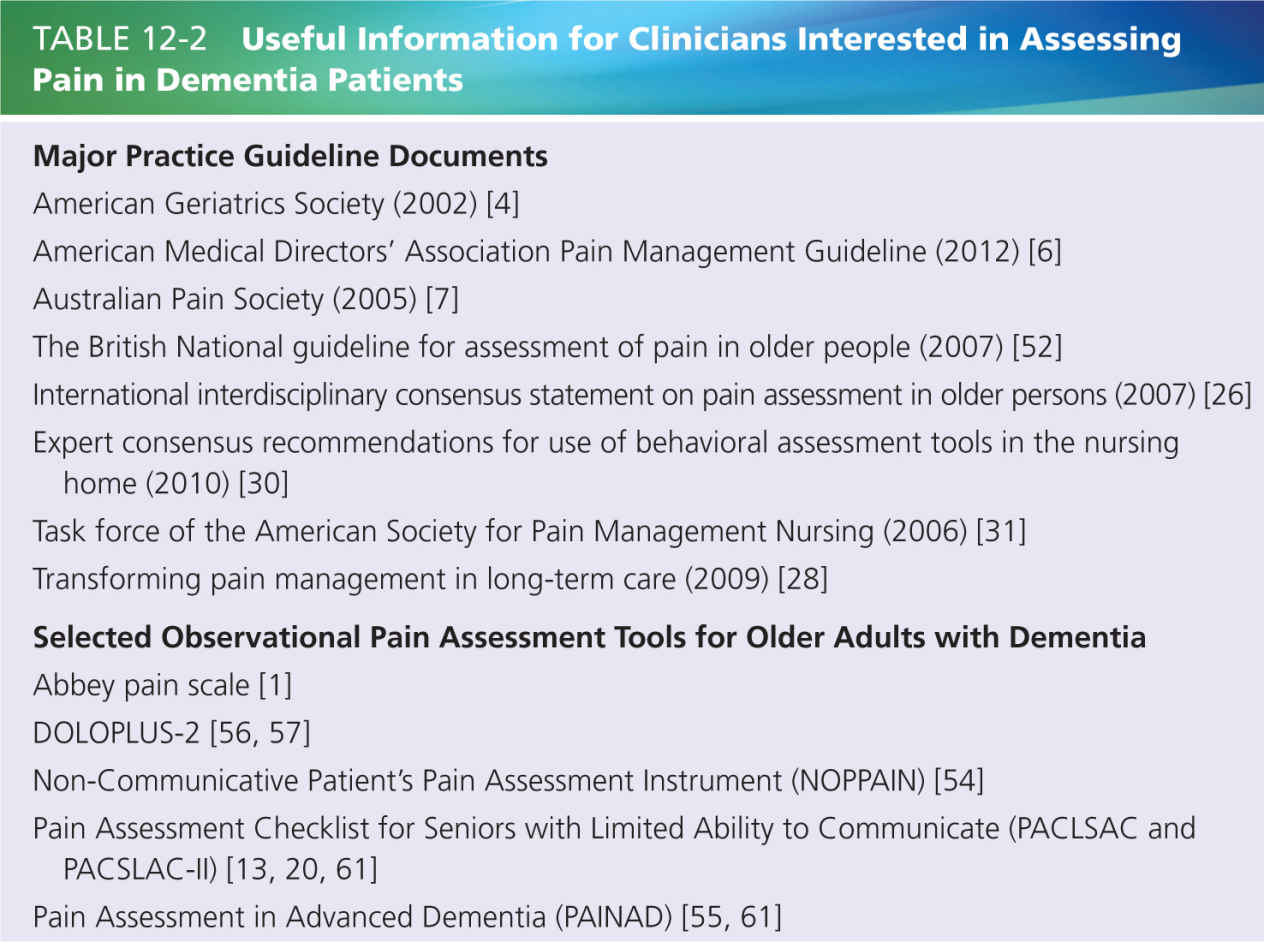

The most recent version of the PACSLAC, the PACSLAC-II [13] is a comprehensive tool that covers all of the domains deemed important by the American Geriatrics Society and contains 31 items (e.g., “a specific sound for pain [e.g., ‘ow, ouch’],” “clenched fist,” “limping”). The tool has been shown to have strong psychometric properties and in psychometric investigation accounted for more variance in differentiating pain from nonpain states than other commonly used pain assessment tools for dementia populations [13].

One key issue concerns the sensitivity of pain behaviors in observational tools. Pain in persons with dementia can result in behavioral disturbance and even delirium [16]. Delirium is a transient altered state of consciousness involving a disturbance of attention and awareness. Delirium also affects judgment [12]. Given the association of pain with behavioral disturbance and delirium, assessment tools include items (e.g., aggression) that may be due to pain but are not specific to pain [29]. Lints-Martindale et al. [43] studied the impact of excluding these types of items (i.e., items most likely to overlap with delirium) from pain assessment tools. They concluded that elimination of those items from assessment tools such as the PACSLAC and the PAINAD did not affect much the ability of the tools to discriminate pain-related from non–pain-related states in that particular investigation. More research is needed to further investigate this issue. It is important to mention, however, that Chan et al. [13] developed the PACSLAC-II in part on the strength of the Lints-Martindale et al. findings. That is, the PACSLAC-II, which is much shorter than the PACSLAC, excluded items most likely to overlap with delirium and effectively discriminated between pain and nonpain states.

FIGURE 12-1 Pain Assessment Checklist for Seniors with Limited Ability to Communicate-II (PACSLAC-II). The subscale names on the PACSLAC-II represent the pain assessment domains recommended by the American Geriatrics Society (2002).

Work completed wordwide has resulted in translations of various observational tools designed for the assessment of pain in dementia. Translations and research on translations of many observational tools are now available in a variety of languages including, but not limited to, Dutch, Italian, Spanish, Japanese, Portuguese, French, Chinese, and German (see reference [25] for review).

Relation of Self-Report and Nonverbal Pain Assessment in Dementia

Labus et al. [40] considered the relationship between self-report and observational measures of pain in cognitively intact samples and concluded that these do not always overlap. Specifically, in a meta-analytic investigation they found that the average association between self-reported pain intensity and observations of pain behavior is moderately positive (r = 0.26) and that a significant relationship is more likely to be found when global observations of behavior and acute (as opposed to chronic pain) are considered. It is probable that, at high intensities, the correlation between pain and nonverbal expressions would increase. Nonetheless, Labus et al. concluded that the relatively low association between self-reported pain and observed pain behaviors demonstrates that self-report and nonverbal responses tap different aspects of the pain experience. The former may be more subject to situational and demand characteristics than the latter which are more likely to tap more immediate and phasic responses to painful stimulation. With this in mind, we can consider the association between nonverbal pain behaviors and self-report in patients with dementia who are capable of responding to questions. The findings concerning this issue are not perfectly consistent across studies. Some studies have failed to find a significant association. For example, Lints-Martindale et al. [43] did not find an association between self-reported pain and a variety of observational measures (e.g., PACSLAC, PAINAD) used to assess movement-exacerbated musculoskeletal pain in older long-term care residents with dementia (average MMSE score of 5.35). In contrast, Lukas et al. [46] found significant associations between the PAINAD, the Abbey, and the Non-Communicative Patient’s Pain Assessment Instrument (NOPPAIN) scales with self-report in participants with cognitive impairments (with average MMSE scores of 13.6). Similarly, Kaasalainen et al. [35] found a high association between self-reported pain and PACSLAC scores in a mixed sample of long-term care residents that included individuals with and without dementia. Differences among the findings of such studies are likely due to sample differences with the Lints-Martindale et al. sample, for example, having MMSE scores that were much lower than those of Lukas et al. The strong possibility that self-reported pain and scores on observational tools tap nonperfectly overlapping aspects of the pain experience underscores the need for using both self-report and observational indices of pain, when possible.

Guidelines for Assessing Pain in Dementia and Limited Ability to Communicate

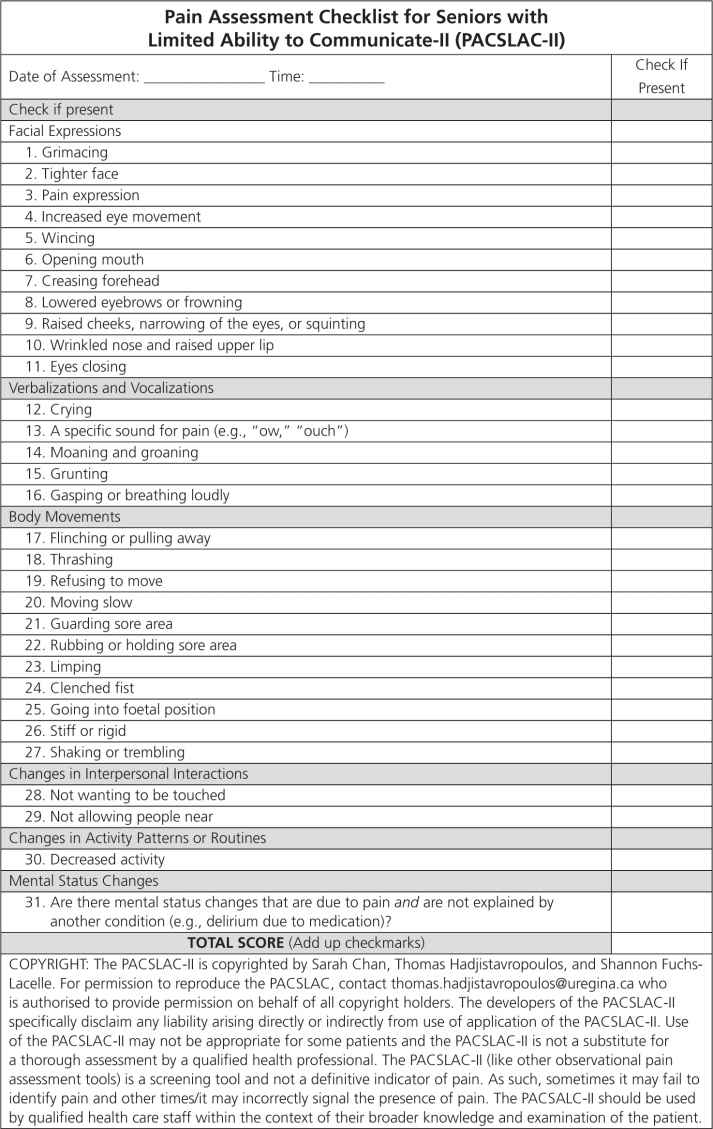

A wide variety of consensus and/or guideline documents [4, 7, 26, 30] provide clinical guidance on how to assess pain in dementia. The reader is referred to the guideline documents for more detailed information. Generally, adopting an individualized approach to assessment is important [6, 26, 52]. That is, it is recommended that pain be assessed on a regular basis (e.g., at least once a week [28]) with the clinician observing the patient’s pattern of scores. A sudden change in a patient’s pattern of scores may be indicative of a change in pain level and would warrant further investigation. Such regular assessments should be occurring under similar circumstances if the scores are to be meaningfully compared across situations (e.g., during a standardized set of movements). Comparing scores before and after the administration of analgesics is useful [26, 31]. Moreover, assessment during movement is more likely to elicit pain behaviors than is assessment during rest [26, 31].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree