20 Lumbar diskectomy is the most commonly performed surgical procedure in the United States for patients experiencing lower back pain or radicular symptoms.1,2 Lumbar fusion is also a commonly performed procedure for the treatment of painful instability of the spine, usually manifesting as chronic low back pain. The safety, efficacy, and cost of these procedures have been questioned in the professional and lay press. This chapter addresses those issues in comparing simple diskectomy versus lumbar fusion for recurrent herniated lumbar disks that were previously treated via diskectomy alone. There is a paucity of data in the literature that directly compare diskectomy versus diskectomy with fusion in such cases. Classic diskectomy alone as treatment for recurrent herniated disk has been reported in many studies and shown to have good results. New techniques for diskectomy have been utilized in the last decade to treat recurrent herniated disk such as microendoscopic diskectomy and endoscopic transforaminal diskectomy. These techniques have the advantage of avoiding scar tissue and epidural fibrosis, and conceptually minimizing the risk for dural tear, which has been a major concern for the surgeon treating recurrences. These techniques may also have an impact on the need for fusion with the occurrence of a reherniated disk (see sample case in Figs. 20.1 and 20.2). There are key issues that remain controversial when comparing both procedures: (1) Is there any clinical benefit from performing a lumbar fusion as compared with a simple decompression when faced with a recurrent disk herniation? (2) What is the added risk of performing a fusion procedure in this setting? A comprehensive review of the literature was performed to adequately evaluate these questions and determine the best evidence available on these issues. A thorough search of the Medline database from 1950 to May 2009 was performed on the topic by using a combination of several key words. A search using the terms “fusion” and “recurrent herniated lumbar disk” yielded 73 articles, whereas one using “diskectomy” and “recurrent herniated lumbar disk” resulted in 223 articles. Subsequently a review of the references of the yielded articles was done for completeness. Case reports and level IV studies were excluded. Furthermore, some studies were also excluded based on age of study or other criteria described below that made them unsuitable to adequately answer the questions at hand. This yielded 20 relevant articles. There were no level I studies, three level II studies,3–5 and 17 level III studies6–22 addressing the topics of interest. Given the papers found, we grouped these studies into two sets. The first represents studies done mainly to assess the results of diskectomy performed for a recurrent disk herniation (eight studies). The second group includes the studies done to assess the results of fusion (12 studies). There was a paucity of studies assessing fusion outcomes in recurrent disk herniation cases. There was only one study identified that directly compared fusion to simple decompression in cases of recurrent disk herniation.11 Only four other relevant studies discussing fusion in this setting were identified.12–15 To draw reliable conclusions, we also included in this section a second set of key studies (seven papers) evaluating fusion in the setting of primary disk herniation and compared this technique to simple diskectomy. There were some overlapping findings between the two groups, which did help further in formulating conclusions and in comparing the two techniques. There are no level I data studies at the present that directly compare the two techniques in the treatment of recurrent lumbar disk herniation. Fig. 20.1 A 45-year-old woman previously underwent L5–S1 bilateral laminectomies and diskectomy at an outside institution. She presents 5 years later with lower back pain and severe hip pain radiating down to the right leg. She underwent a short trial of conservative therapy (medications, physiotherapy). However, the radicular pain proved to be excruciating in nature; to the point where she was unable to pursue any further conservative measures. On examination, lower extremity strength revealed weakness, mainly in the right hamstrings, gastrocnemius, extensor hallucis longus, and tibialis anterior (3- to 4- out of 5-power). She had decreased sensation in L5–S1 distribution along the right side to temperature. She showed difficulty ambulating secondary to the pain. Straight leg raise testing was positive at 10 degrees on the right side. (A,B) Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine with axial (A) and sagittal (B) T2-weighted images revealed a large L5–S1 reherniated disk along the right lateral aspect with compression of the L5 nerve root. (C) There was also evidence of a complete laminectomy of the L5–S1 and diskectomy, as well as some modic changes at the L5–S1 disk space. From the many level II studies available in the literature we excluded from our analysis all those involving a herniation of a disk at a different level in a previously operated patient, studies that reviewed patients treated over a period of more than 2 decades, and studies recruiting patients only based on hospital registry diagnoses. Isaacs et al3 prospectively analyzed a series of 10 consecutive patients with recurrent herniated disk previously operated on via a microendoscopic diskectomy (MED) and reoperated on with the same technique. Results were then compared with those of a control group of 25 patients treated for primary disk herniation with the same technique. All the patients enrolled in the study fulfilled the following criteria radicular pain, radiographic findings of herniated disk at the same level and the same side of the previous operation with residual lateral recess or foraminal stenosis. Patients who showed signs of lumbar instability were excluded from the study. The main difference in the two groups was the distribution of the level of herniation being L5–S1 predominant in the revision surgery group (70%), whereas L4–L5 was the predominant level of herniation in the control group (60%). There was no statistically relevant difference in the operative time, blood loss, and hospital stay between the two groups. Analysis of complications showed one cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak and one recurrent disk in each group. The revision surgery group was then assessed using Macnab’s criteria (see Table 20.1) at short-term follow-up (average 13.1 months) and showed that 90% of patients had outcomes ranging from good to excellent. Reported data regarding the control group were sparse and included complications (one dural tear and one CSF leak), with very little information on overall clinical outcome. Overall there were no substantial differences in outcomes between groups. Fig. 20.2 The patient underwent an L5–S1 right-sided redo open diskectomy and complete facetectomy with decompression of the nerve roots at that level. This was followed by posterior lumbar interbody fusion, posterolateral arthrodesis, and bilateral pedicle screw fixation (done by the senior author, RN). Her pain improved significantly postoperatively. She did have residual weakness in her right tibialis anterior and extensor hallucis longus. (A,B) A computed tomographic scan, obtained shortly after surgery with mid-sagittal (A) and parasagittal (B) reconstructed images, demonstrated adequate alignment and position of the instrumentation and (C) magnetic resonance imaging showed an open foramen at L5–S1 with adequate resection and decompression. At 1-year follow-up, her “foot drop” and her radicular and back pain continued to improve. Criticism of this study includes the limited number of patients, which does not provide an adequate statistical power to demonstrate statistical significance. Follow-up was complete for all patients but was too short to adequately assess long-term efficacy of either technique (average follow-up was only 13 months). Hoogland et al4 reported a prospective cohort evaluation study of 262 patients treated for recurrent lumbar disk herniation by means of endoscopic transforaminal diskectomy (ETD) over a 10-year period with a 2-year follow-up. Patients were enrolled in the study if they developed a new disk herniation after at least a 6-month pain-free interval, clinically showed a clear radiculopathy with acute onset, and had a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan that demonstrated a recurrent disk herniation. All patients were treated with standard ETD procedure with widening of the foramen under local anesthesia. Periradicular scar tissue was not removed. Patients were examined the day after surgery and at 3 months. The 2-year follow-up was completed by 238 patients; they were evaluated in terms of body capacity rating according to Mcnab’s criteria, an assessment of leg and back pain relief according to the 10-point visual analogue scale (VAS), and overall clinical improvement including participation in sporting activities. Recurrence rate and complications were also analyzed. Twenty-four patients were lost after the 3-month follow-up (at that time only 8.5% showed unsatisfactory results). Results at 2-year follow-up were satisfactory (according to Mcnab’s criteria) in 80.67% of cases. An average improvement in VAS score for leg pain of 5.85 points and 5.71 for back pain was also seen. Eleven patients were unsatisfied with the procedure (4.62%), and nine of them required further intervention. Disk herniation recurrence was considered a herniation that occurred 3 months after the revision operation. Eleven patients had recurrences (4.62%) within the first 2 years and were re-treated (four with ETD, one with fusion, six with microscopic decompression). Complications of the procedure included three cases of irritation of nerve root and six recurrent lumbar disk herniations within 3 months. No infections or dural tears were reported. Table 20.1 Macnab’s Classification

Recurrent Lumbar Disk Herniation: Repeat Diskectomy versus Fusion

Group 1—Diskectomy for Recurrent Lumbar Disk Herniation

Group 1—Diskectomy for Recurrent Lumbar Disk Herniation

Level I Data

Level II Data

Results | Complications |

|---|---|

Excellent | No pain, no restriction of activity |

Good | Occasional back or leg pain not interfering with the patient’s ability to do his or her normal work, or to enjoy leisure activities |

Fair | Improved functional capacity, but handicapped by intermittent pain of sufficient severity to curtail or modify work or leisure activities |

Poor | No improvement or insufficient improvement to enable an increase in activities/or further operative intervention required |

Cinotti and colleagues5 reported a cohort study analyzing data from 26 patients operated on over a 3-year period for recurrent herniated disk. The control group was represented by 50 patients operated on for a primary disk herniation during the same period of time and who were pain free at follow-up. The study hypothesis was to assess whether diskectomy for recurrent herniated disk carried any risk factors and to compare the results with those of surgery for a primary herniated disk. All patients were operated on using a standard interlaminar approach with a limited laminotomy and removal of the medial one third of the facet joints. If lateral recess stenosis was present, bone removal was extended caudally to achieve decompression of the neural elements. Inclusion criteria were absence of pain for at least 6 months after the first operation, MRI findings of recurrence at the same level and side (or, with inconclusive MRI results, exclusion of the presence of any other spinal condition that materially affected a patient’s symptoms or treatment), and nonresponsiveness of the patient to conservative treatment. Patients were assessed before their first surgery, between the two surgeries, and at a minimum of 2 years following their reoperation. Overall clinical outcome was evaluated using a 100-point grading system taking into account severity of pain, patient satisfaction, functional status, and physical examination. Analysis of patients from the study group who had a recurrence showed that 42% of patients could associate the recurrence with a single event, suggesting that the incision in the anulus done during the first surgery may create a locus minoris resistentiae (or weak point, i.e., a place of lower resistance within the anulus, where the disk can reherniate through). Disk degeneration was more severe in the study group than in the control group (p = 0.002). Two years after operation 88% of the control group and 85% of the revision group demonstrated overall satisfactory outcome (excellent or good). Four patients from the study group that had a fair outcome demonstrated one case of recurrence, one case of diskitis, and two with only mild improvement in symptoms. One of the two patients with mild improvement showed only a bulging disk at the time of operation. Two patients had dural tears that did not require any suturing. The authors concluded that with accurate patient selection, repeated diskectomy can be performed with a high rate of success.

Though well conducted, this study had a limited number of patients that does not allow one to draw any definitive conclusions. The process of assignment to either the study or the control group was not blinded to those performing the final assessment, which is a bias to this investigation. However, the assessment process used appropriate measurements that addressed the study questions, and the measurements were accurate and precise. There were very few differences between the study and the control group other than the recurrence of herniated disk (in the control group there was a higher percentage of female patients). The authors performed a complete diskectomy in 320 patients and a partial diskectomy in 40 patients. It is unclear how many patients of the study group and control group actually received complete or partial diskectomy. Treatment tailoring, which is considered good clinical practice in general, does create biases when closely examined and should have led to the consideration of a separate subgroup for analysis.

Level III Data

Papadopoulos et al6 conducted a retrospective study on 51 patients that were operated on for removal of a recurrent herniated disk at the index disk level and same side as the primary operation. They compared these results to a control group of 50 patients who underwent disk excision for a primary herniated disk. Mean ages of patients were 39.2 years and 38.2 years, respectively. Inclusion criteria were relief from radicular and back pain for at least 2 months after the first operation, recurrence of similar pain, failure of conservative treatment, and MRI findings of a recurrent disk herniation at the same level and side. Exclusion criteria were segmental instability, foraminal stenosis, epidural fibrosis, and adhesive arachnoiditis. All patients were operated on with a classic microdiskectomy technique, but data regarding removal of scar tissue and the size and physical description of the disk herniation were not noted. Patients in the revision group were followed for an average of 40.9 months, whereas the control group members were followed for an average of 53.5 months. All patients were evaluated with the Muskuloskeletal Outcomes Data Evaluation and Managements System (MODEMS).6 The results showed no statistical significance in terms of overall satisfaction, reporting improvement in 80% of the primary group and in 85% of the revision surgery group. Thirty percent of revision surgery patients reported a greater improvement after the second surgery. Statistically significant differences were found when analyzing the frequency of lower back pain, leg pain, and frequency of numbness/tingling in the leg or foot, which were considerably worse in the revision group.

There are several problems with this article. The authors define recurrence as radicular pain commencing 2 months following the primary operation. This is often considered a complication by many surgeons. The compliance of patients answering the questionnaire was very low, at 52.9% for the recurrent herniated disk group and 60% in the control group. This dropout rate may account for true differences in the actual results, if responses from a greater majority of patients were available.

Dai et al7 retrospectively reviewed a group of 39 consecutive patients treated over a 15-year period with a repeat diskectomy for a recurrent lumbar disk herniation. The average age was 48 years (range, 27 to 72 years). Inclusion criteria were pain-free interval of at least 3 months and herniation at the same level on either side. Five patients from this group had been operated on twice or more previously on other lumbar disk levels. The initial procedure varied: three underwent percutaneous diskectomy, 22 had a diskectomy with laminotomy, six underwent a diskectomy with unilateral hemilaminectomy, seven underwent a diskectomy with bilateral total laminectomy, and one underwent a diskectomy with bilateral laminectomy and posterolateral noninstrumented fusion. A partial facetectomy was also performed in an additional 12 patients. The average time between the first operation and the disk herniation recurrence was 5 years and 4 months (range, 6 months to 17 years). Duration of symptoms ranged from 2 months to 10 years. All patients were evaluated preoperatively using the Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) score (see Table 20.2) (average score 12.0). Preoperative imaging studies included computed tomographic (CT) scanning, myelogram, or MRI with or without contrast. Seven patients had associated spinal stenosis unrelated to the recurrent disk herniation. Indications for the second operation included intractable pain or cauda equina syndrome. The surgical procedure for the recurrent disk herniation involved two laminotomies, 17 hemilaminectomies, and 20 bilateral total laminectomies. Decompression for severe spinal stenosis was also performed in addition to the diskectomy. Four patients who underwent a bilateral total laminectomy had an associated degenerative spondylolisthesis and subsequently underwent a posterolateral fusion with transpedicular screw fixation. A dural tear occurred in seven cases. The average follow-up was 25 months with an average recovery rate of 72%. Results were reported as excellent in 29 cases and fair in 10 cases. No differences were reported between the fused and not fused patients in the group of patients who underwent total bilateral laminectomies. In the repeat diskectomy cases, only the herniated fragment was removed without curettage of the disk space. The authors indicated a fusion in patients where segmental instability was inevitable after surgery or in patients where a preexisting instability was expected to progress after decompression.

Subjective Symptoms | Evaluation | Score |

|---|---|---|

Lower back pain | None Occasional, mild Occasional, severe Continuous, severe | 3 2 1 0 |

Leg pain and/or tingling | None Occasional, light Occasional, severe Continuous, severe | 3 2 1 0 |

Gait | Normal Able to walk farther than 500 m, although it results in symptoms Unable to walk farther than 100 m | 3 2 0 |

Clinical Signs |

|

|

Straight leg raising test | Normal 30 to 70 degrees < 30 degrees | 2 1 0 |

Sensory disturbance | None Slight disturbance (not subjective) Marked disturbance | 2 1 0 |

Motor disturbance | Normal Slight weakness (MMT 4) Marked weakness (MMT 3 to 0) | 2 1 0 |

Restriction of Activities of Daily Living | Impossible | Difficult |

Turning over while lying | 0 | 1 |

Standing up | 0 | 1 |

Washing face | 0 | 1 |

Leaning forward | 0 | 1 |

Sitting about an hour | 0 | 1 |

Lifting or holding heavy object | 0 | 1 |

Running | 0 | 1 |

Urinary bladder function | Normal Mild dysuria Severe dysuria | 0 −3 −6 |

Abbreviation: MMT, manual muscle testing.

Note: Recovery rate (%) in JOA score is calculated as (postoperative score – preoperative score)/(29- preoperative score) × 100.

Ahn et al8 retrospectively reviewed a series of 43 consecutive patients with a recurrent herniated disk who were operated on via a percutaneous endoscopic lumbar diskectomy. Inclusion criteria for the study included an open surgical procedure done for the primary surgery, a pain-free interval of a minimum of 6 months, same disk level herniation (including disk herniation on the opposite side), and lack of response to conservative treatment. Patients were evaluated using the MacNab criteria and visual analogue scale (VAS) scores. The statistical analysis of the patient population revealed successful outcomes in 81.4% of cases (excellent in 27.9% and good in 53.5%) by the MacNab criteria. Improvement in VAS score was also seen, with a starting mean score of 8.72 ± 1.20 and end score of 2.58 ± 1.55. If subgroups of patients were then taken into consideration, the results changed according to the patients’ age, time of onset of symptoms, and presence of lateral recess stenosis. Patients younger than 40 years and those in which symptoms started less than 3 months prior to the reoperation had better outcomes. An interesting finding was that only 33.3% of patients with lateral recess stenosis had a favorable outcome.

In this study, the sample size was too small to show strong statistical power. A much larger series would be necessary to consider these subgroups of patients. No clear data relating to the patients’ preoperative status were reported. No control group was examined.

Suk et al9 reported a series of 28 patients that were operated on via conventional open diskectomy for recurrent lumbar disk herniation. Inclusion criteria were recurrent disk herniation confirmed by MRI, failure of conservative treatment for 6 to 8 weeks, and a positive tension sign. The mean pain-free interval was of 60.8 months. Herniation was ipsilateral in 21 cases and contralateral in seven cases. Degree of herniation was also considered, and recurrent patients were found to have a significantly larger disk herniation when compared with the size of the primary disk herniations. Clinical improvement was seen in 71.1% of recurrences compared with 79.3% of initial surgeries. The procedure for the second diskectomy lasted longer than the primary operation. Patients operated on with an ipsilateral herniation fared better in terms of clinical outcome than a contralateral recurrence group.

Some criticism to this study lies in the lack of a control group, the small number of patients, and the fact that duration of follow-up was missing. In the results section, there was no clear explanation as to which kind of evaluation was used to assess the improvement.

Palma et al10 reported their series of reoperation for recurrent lumbar disk herniation. During a 45-month period, 95 patients were treated, 42 of which were previously treated at the same institution. Patients were assessed using the MacNab criteria 2 to 10 years after surgery (mean, 4 years). The mean pain-free interval after the first surgery was 55 months (range, 3 to 120 months). Of observed recurrences, 11.5% were seen within 6 months from the first operation, and 80% were seen within 2 years. In all cases the herniation was ipsilateral to the first herniation and at the same level. In 4.8% of recurrent cases, the primary operation consisted of the removal of the herniated disk fragments without entering the intervertebral disk space with any instrument. The herniated disk and eventual fibrosis was found in 91 cases. In the remaining four cases, MRI did not show clear evidence of herniation, and these patients were operated on based on the clinical presentation. A dural tear occurred in 4.2% of cases. In 89% of cases the outcome was rated as excellent or good, compared with 95% of cases after the first operation. Poor results were reported in 2% compared with 0.5% in the initial procedure.

This study did not compare results to a control group. Sample size was good to extrapolate conclusions that might be applicable to other patients with the same condition. Some of the patients were operated on elsewhere, which could be a confounding factor.

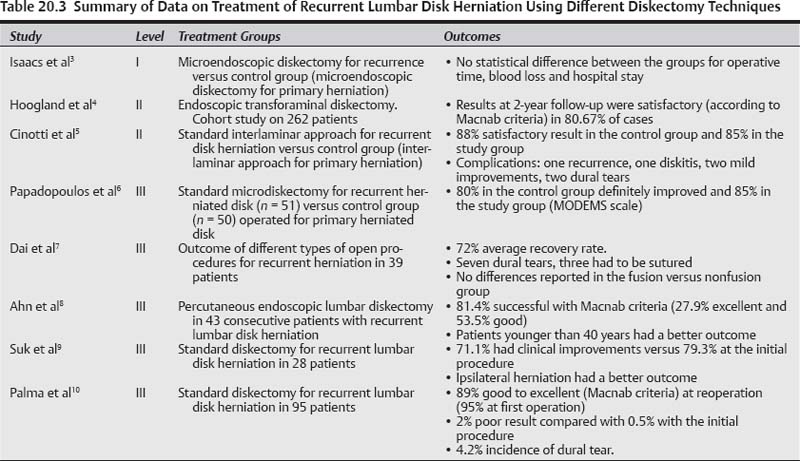

Summary of Data for Group 1 (see Table 20.3)

Recurrence of herniated disk has been reported in the literature to range from 5 to 11% of cases undergoing diskectomy. Most of the series that we found reported their results from repeated diskectomy for recurrent herniated disk with the following inclusion criteria: a pain-free interval was observed between the initial and the repeat procedure; there were MRI findings of a herniation; there was failure of a trial of conservative treatment. These studies have shown results similar to those seen in patients operated on for a primary herniated disk, which are overall favorable. Cohort studies are particularly helpful in these cases to assess risk factors for repeated surgery. In the series where patients were operated with the endoscopic techniques, the results were also as favorable.

Group 2—Fusion for Lumbar Disk Herniation

Group 2—Fusion for Lumbar Disk Herniation

Given the paucity of studies discussing results of fusion after prior diskectomy, we have elected to loosen our inclusion criteria with regard to dates of publications and have also elected to discuss relevant studies done in the pre-MRI era that remain important to address the question at hand. There were several important studies comparing diskectomy and fusion for primary disk herniation that are worth discussing as well. These studies did not specifically look at outcomes and differences in management of recurrent lumbar disk herniation after previous diskectomy, but they provide important points in comparisons of fusion to diskectomy alone as a primary procedure. Although there were some cohort studies discussed in the latter subgroup, most provide class III evidence with regard to the question at hand.

Level III Data

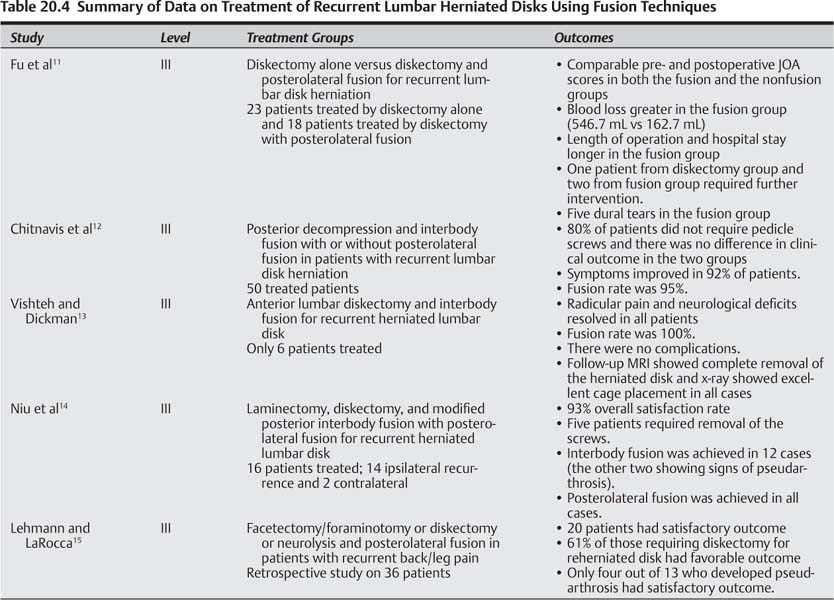

Part 1—studies Performed for recurrent disk Herniation (see table 20.4)

Fu et al11 presented a retrospective study in which they analyzed and compared the outcomes of two groups of patients that suffered from a recurrent disk herniation. The first group consisted of patients operated on by diskectomy alone, whereas the second group underwent diskectomy and a posterolateral fusion. During a 6-year period 65 patients who underwent reoperation for recurrent herniated disk were examined. Four patients were lost at follow-up and the remaining 61 patients (93.8%) were reviewed. Inclusion criteria were the presence of radicular pain, failure of at least 6 months of conservative treatment, and true recurrent disk herniation (ipsilateral and at the same level of the primary disk). Forty-one patients met the inclusion criteria. Twentythree patients were treated by disk excision alone. Postero-lateral fusion with transpedicular screw placement was performed in 18 patients that required facetectomy for the clear identification of the nerve root. Follow-up of a minimum of 60 months was performed. Intraoperative blood loss, length of surgery, and hospital stay were also examined. Symptoms were assessed before and after surgery using the JOA score (see Table 20.2). The mean preoperative score was 9.5 in the diskectomy group versus 8.7 for the fusion group that improved to 25.3 and 25.6, respectively (29 is the score for a normal subject), at follow-up. Clinical outcome was rated excellent or good in 78.3% patients of the diskectomy group and 83.3% of the fusion group. Blood loss, as expected, was greater in the fusion group (546.7 mL on average) compared with 162.7 mL in the nonfusion group. Length of operation and hospital stay were also longer in the fusion group. In the nonfusion group, one patient required further intervention for back pain and sciatica after 69 months; whereas in the fusion group, two patients required intervention, respectively, for back pain (38 months after surgery) and for adjacent level instability. Five patients from the fusion group sustained a dural tear.

This was the only study that directly compared the two techniques in the setting of a recurrent herniation. The patients of the fusion group underwent fusion with transpedicular screws because of potential instability due to a previous facetectomy. This may represent a limitation of the study because only patients with potential iatrogenic instability were fused. Another limitation included the selection criteria for the two groups, which, by the nature of the study, were not randomized. This, however, does represent a typical selection done in many clinical practices and is a form of tailoring treatment based on individual scenarios.

Chitnavis et al12 reported on patients with recurrent disk herniations and symptoms of back pain or signs of instability who underwent posterior decompression and interbody fusion. Inclusion criteria for fusion were symptoms of neural compression, tension signs, and lower back pain with focal disk degeneration and nerve root distortion as depicted on MRI. Patients with recurrent disk herniation without low back pain or instability were excluded. Clinical outcome was assessed using the Prolo Economic Scale.23 Fusion outcome was assessed using an established classification. In 40 patients (80%) pedicle screw fixation was not used. Symptoms improved in 46 patients (92%), and 45 patients (90%) stated that they would undergo the same operation again. Two thirds of patients experienced good or excellent outcomes (Prolo score greater than 8) at both early and late follow-ups. There were no differences in clinical outcome between patients undergoing placement of pedicle screws and those who did not (p = 0.83, Mann–Whitney U-test). Of the 50 patients with 6 months to 5 years follow-up data, 92% improved and 90% were very satisfied with their outcome. The fusion rate was 95% and the complication rate was low.

This study demonstrated that recurrent lumbar disk patients who also have degenerative changes and lower back pain (or axial pain), can be treated successfully via posterior fusion, with good expected outcomes.

Vishteh and Dickman13 presented a small series of five patients with recurrent sequestered disk herniations treated by anterior lumbar diskectomy and interbody fusion alone. The six patients underwent a muscle-sparing “minilaparotomy” and subsequent microscopic anterior lumbar micro-diskectomy with fragmentectomy for the recurrent lumbar disk extrusions at L5–S1 (four patients) or L4–L5 (two patients). A contralateral distraction plug permitted ipsilateral dissection under the microscope. The extruded disk fragments were excised by opening the posterior longitudinal ligament. Interbody fusion was then performed using a cage device or bone dowel. There were no complications, and blood loss was minimal. Follow-up MRI revealed complete resection of all herniated disk material. Plain films revealed excellent interbody cage position. Radicular pain and neurological deficits resolved in all six patients (mean follow-up of 14 months). The authors concluded that anterior lumbar microdiskectomy with interbody fusion provided a viable alternative for recurrent lumbar disk herniations. The results were very good in all five patients: The fusion rate was 100%, and all had relief of leg pain.

These series provide class III evidence in support of performing a fusion at the time of reoperative diskectomy, particularly in patients with associated deformity, instability, or chronic axial back pain. Another point in this study is the demonstration that an anterior diskectomy can be sufficient for neural decompression.

Niu et al14 reported a series of 16 patients operated on over a 16-month period for recurrent herniated lumbar disk. Inclusion criteria were the presence of herniated disk at the same level identified by gadoliniumenhanced MRI, unilateral leg pain of at least 3-month duration, and failure of conservative care. Two patients had herniation on the contralateral side, whereas the rest were ipsilateral. Two patients were lost at follow-up. Fourteen patients were followed by interview and examination at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months and then annually. After laminectomy and diskectomy a modified posterior lumbar interbody fusion was performed (modified PLIF). A single cylindrical cage was inserted after facetectomy, via a posterolateral approach, on the opposite side of the previous operation through virgin tissue. The cage was filled with bone harvested from the ilium. After facetectomy, pedicle screw fixation and postero-lateral fusion were performed. The mean duration of the procedure was 230 minutes, the mean blood loss was 623 mL, and the mean follow-up time was 25 months (range, 17 to 36 months). The fusion status was determined by lumbar radiographs. Clinical outcome was assessed by evaluating residual back/radicular pain, the need for medication, and return to work status. Clinical outcome showed 93% overall satisfaction rate. Posterolateral fusion was achieved in all patients. Five of these patients suffered from discomfort during waist bending and lifting due to screw impingement, and the screws had to be removed at 1 to 2 years after surgery. Interbody fusion was achieved in 12 of the 14 patients. The two patients who did not achieve interbody fusion showed radiographic signs of pseudarthrosis.

Of note is that the authors themselves state the following: “This study is not designed to indicate when to fuse an RLDH [a recurrent lumbar disk herniation]. This study suggests that the single long diagonal PLIF cage after unilateral facetectomy combined with PLF and unilateral pedicle-screw fixation provides satisfactory results in treating RLDH whenever fusion is indicated.” Due to the small sample size, this is considered class III evidence. The study sample was too small to give a clear indication of the use of this technique for treatment of recurrent herniated lumbar disks. Two patients were lost to follow-up, and the characteristics of these patients were not described nor were the reasons why they could not be followed. Five patients had to undergo another operation for removal of the posterolateral instrumentation, which put them at risk of having to undergo repeat general anesthesia, the risks of infection, and other general surgical risks as well.

Lehmann and LaRocca15 performed a retrospective study on 36 patients affected by chronic back pain and/or leg pain after one or more previous lumbar surgeries who were treated by canal exploration and spinal fusion. Patients were categorized in groups as follows: radiculopathy in 18 cases, instability in 13, and pseudarthrosis in five. Thirteen patients had recurrent herniated disks. Posterolateral fusion (PLF) was performed in addition to wide lateral bony decompression in 23 patients and diskectomy in 13. Neurolysis was also required in 15 patients. Postoperative complications included 10 wound hematomas, donor site pain in four patients, CSF leaks in two, and meningitis in one. Mean follow-up was 3 years. Twenty patients had a satisfactory outcome. In the subgroup of patients with recurrent disk herniations (13 patients), eight (or 61%) had a favorable outcome after fusion. Patients operated on more than 18 months after previous surgery did better than those operated before 18 months. Fusion rate was reported in 23 patients (64%), with 17 of these patients having satisfactory outcome. Only four of the 13 patients who developed pseudarthrosis reported satisfactory outcome.

Even though this study did not directly assess only patients with recurrent herniated disks having undergone previous diskectomy, it did include a subset of such patients. Unfortunately the sample size was too small to draw definitive conclusions from that subgroup of patients. The majority of patients were operated on by posterior and lateral decompression with posterolateral fusion for stenosis. The other subgroups discussed did slightly better than those with recurrent herniation. Where pseudarthrosis was the main reason for revision surgery the patients had the worst outcomes. If fusion was achieved the results were better. The study was performed in a pre-MRI era, which did not allow the authors clear differentiation of recurrent disk herniation and other causes of failed surgery and back/leg pain. Selection criteria were varied; therefore surgery was tailored to alleviate different sources of back and leg pain. There was also no control group.

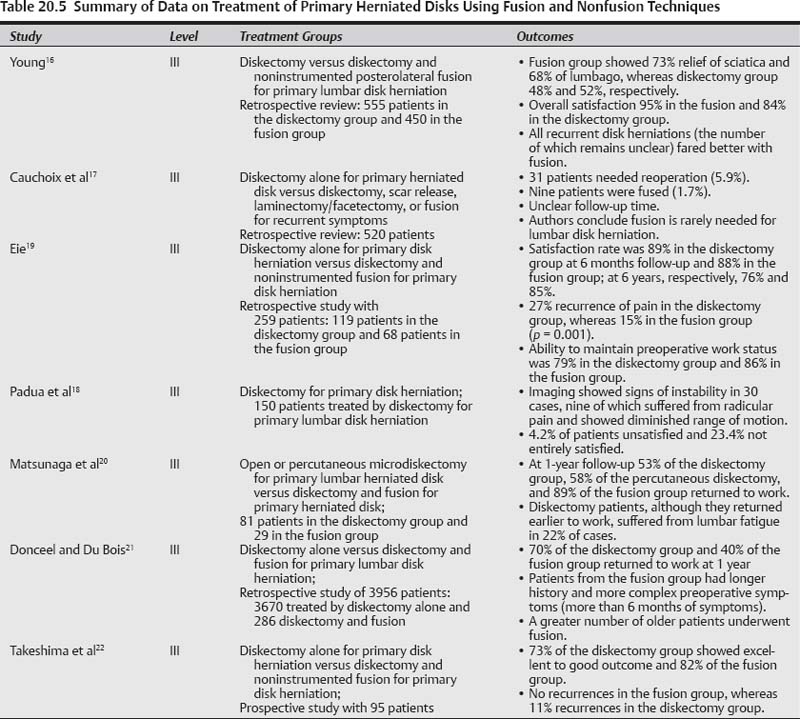

Part 2—studies Performed for Primary disk Herniation (see table 20.5)

Resnick et al,24 in their meta-analysis discussing the performance of fusion on lumbar disk herniation, completed a thorough review of studies on fusion in the setting of primary disk herniation, thereby formulating important guidelines. The papers of interest from this publication are further briefly discussed herein and results summarized in Table 20.5.

A retrospective review was done by Young on a large series of patients who underwent surgery for a lumbar disk herniation at the Mayo Clinic.16 During a 40-year period, 450 patients underwent diskectomy and noninstrumented PLF, and 555 underwent diskectomy alone. The authors reported a 95% patient satisfaction rate in the fusion group and an 84% satisfaction rate in the diskectomy alone group. In another series of 520 patients with herniations treated by diskectomy alone during an 18-year period, Cauchoix et al17 found 31 patients (5.9%) in whom signs or symptoms of mechanical lumbar instability subsequently developed and who eventually required fusion. Both of these studies were done during the pre-MRI era, and in the latter, diagnosis of instability was based on plain x-ray and CT scan.

In the post-MRI era, Padua et al18 studied 150 patients who underwent primary lumbar diskectomy. Thirty patients displayed radiographic signs of instability, yet only nine were believed to be symptomatic. The incidence of symptomatic lumbar spinal instability was relatively low. The authors concluded from these large cohorts that only a small percentage of herniated disks require fusion.

Eie examined 259 patients with a herniated disk who underwent one of two treatments: diskectomy alone (119 cases) or diskectomy and noninstrumented PLF (68 cases).19 The authors observed equivalent rates of good outcome between the two treatment groups during the first few months after surgery (89 and 88%, respectively). At 6 years postsurgery, 76% of the diskectomy-alone group reported satisfactory results compared with 85% of the diskectomy with fusion group. Manual laborers and those with significant preoperative axial back pain were more likely to suffer recurrences of pain when treated with diskectomy alone.

Matsunaga et al20 performed a retrospective review of 80 manual laborers and athletes treated with diskectomy alone (either open or percutaneous) (51 subjects) or with open diskectomy combined with fusion (29 subjects). Their primary outcome measure was return to work or participation in athletics. At 1 year they observed that 54% of the diskectomy group and 89% of the diskectomy with fusion group were able to return and maintain preoperative work or athletic activities. They coined the term lumbar fatigue for those that could not maintain their previous activity level. In general, more active patients such as manual laborers and athletes fared better after spinal fusion over a prolonged period of time.

Donceel and Du Bois21 reported a series of 3956 patients treated for a lumbar disk herniation with either diskectomy alone (3670 patients) or diskectomy and fusion (286 patients). The poorest overall outcomes were present in the fusion group. This retrospective review strongly suggested that diskectomy combined with fusion does not improve outcomes in patients compared with diskectomy alone when surgically treating lumbar disk herniation.

Takeshima et al22 performed a prospective study on 95 patients treated with surgery for a primary disk herniation. Forty-four patients underwent diskectomy alone and 51 underwent diskectomy and fusion. In 73% of the diskectomy-only group an excellent or good score was achieved, compared with 82% of the diskectomy plus fusion group. Although the results were better in the fusion group, this difference was not statistically significant.

Summary of Data for Group 2 (see Tables 20.4 and 20.5)

There was only one study identified that specifically discussed outcomes after previous diskectomy with recurrent herniation comparing reoperative diskectomy alone versus fusion.11 Fusion was shown to have some theoretical benefits, such as minimizing the risk for recurrence, favoring a better long-term outcome in athletes and heavy laborers. There were, however, no significant differences in outcome between the diskectomy and the fusion groups in general. The risk of other complications (e.g., dural tear, blood loss, length of stay, etc.) seemed to be higher in the patients treated with fusion. Adjacent-level instability should also be considered within the risks of fusion because it exposes the patient to the possibility of requiring a second invasive procedure.

There is no convincing medical evidence to support the routine use of lumbar fusion at the time of a primary or recurrent lumbar disk resection. The evidence regarding the potential benefit of the addition of fusion remains unclear and conflicted. Therefore, the definite increase in cost and complications associated with the use of fusion are not always justified. Patients with preoperative lumbar instability may benefit from fusion at the time of lumbar diskectomy; however, the incidence of such instability appears to be very low (less than 5%) in the general lumbar disk herniation population. Patients who suffer from chronic low back pain, or are heavy laborers or athletes with axial low back pain, in addition to radicular symptoms may be candidates for fusion at the time of their initial lumbar disk excision.

Conclusions

Conclusions

We have conducted a thorough review of studies discussing outcomes of reoperative diskectomy or reoperative diskectomy combined with fusion. Overall outcomes appear to be satisfactory in both cases.

According to the guidelines for the performance of fusion procedures for degenerative disease of the lumbar spine,24 there remains insufficient evidence to recommend a treatment standard or a treatment guideline. However, the following options are recommended:

1. Reoperative discectomy is recommended as a treatment option in patients with a recurrent lumbar disk herniation.

2. Reoperative discectomy combined with fusion is recommended as a treatment option in patients with a recurrent disk herniation associated with lumbar instability, deformity, or chronic axial low-back pain.

Patients with a recurrent disk herniation have been treated successfully with both reoperative diskectomy and reoperative diskectomy combined with fusion. According to the “guidelines” for the performance of fusion procedures for degenerative disease of the lumbar spine introduced in 2005 by the American Association of Neurological Surgeons/Congress of Neurological Surgeons,24 patients with a recurrent lumbar disk herniation with associated spinal deformity, instability, or associated chronic low back pain (or “axial” pain), consideration for fusion in addition to reoperative diskectomy is recommended. There remains, however, conflicting evidence for the use of a lumbar fusion in the treatment of recurrent lumbar disk herniation in the absence of the foregoing associated factors. Our review of the literature has yielded the same observations and results as the ones suggested by the guidelines. Clearly, careful patient selection and treatment tailoring are of paramount importance in determining a candidate for reoperation, particularly when surgical fusion is considered.

• There is no convincing medical evidence to support the routine use of lumbar fusion at the time of a primary or recurrent lumbar disk resection.

• The definite increase in cost and complications associated with the use of fusion is not always justified.

• Patients with preoperative lumbar instability may benefit from fusion at the time of lumbar diskectomy.

• Patients who suffer from chronic low back pain, or who are heavy laborers or athletes with axial low back pain, in addition to radicular symptoms may be candidates for fusion at the time of their initial lumbar disk excision.

• Reoperative diskectomy is recommended as a treatment option in patients with a recurrent lumbar disk herniation.

• Treatment tailoring and patient selection are of great importance when determining a candidate for reoperation, especially when surgical fusion is considered.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree